Biometrics: The biggest threat to human rights since WW2 or a useful tool to prevent crime?

In a world driven by data, what makes you, you? The multibillion-dollar industry of biometrics is changing everything we know about identity, privacy and anonymity. Steve Boggan investigates

Have you ever wondered what makes you, you? Is it a name or your ability to prove it is yours? Is it the fact that you have a card or a piece of paper with that name on it? And in a world where identities can be so easily forged or stolen, what’s to say another believable – but criminal – version of you isn’t out there right now doing unspeakable things?

These are questions that have given rise to the modern biometrics industry, a £26bn-a-year global business that is casting aside hard anachronistic analogue proofs of identity and replacing them with digitised representations of your unique physical attributes.

Already, you can switch on your phone or computer just by looking at it. That’s facial recognition technology. Or you might use the “dactyloscopic” function on your computer to turn it on – put simply, you’d have your fingerprint read by a pad on your PC.

So far, so convenient.

But did you know that the way you talk is unique to you? And the way you walk? So is the shape of your earlobe and of your hand or the delicate patterns of your iris or the meandering outlines of your veins. Even the way you type can identify you.

All, or any, of these make you, you, a staggeringly wonderful product of nature and evolution – and who wouldn’t want to rely on any of these beautiful characteristics as proof of identity over a dreary passport or driving licence or ID card?

Deploying remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces means the end of anonymity in those places

It might surprise you, then, to learn that the use of biometrics to identify people in public is being seen as the single biggest threat to civil liberties and human rights since the Second World War. All over the civilised world, electronic privacy campaigners, freedom advocates, computing demi-gods – even the pope – are calling for a moratorium on the use of facial biometrics with artificial intelligence surveillance systems, which, they argue, could see an end to anonymity as we know it.

Last month the two most important bodies overseeing data protection issues in the European Union called for a ban on the use of mass surveillance systems that make use of biometrics with AI in public places; systems that can track and identify hundreds or thousands of people at once.

In a joint statement, Andrea Jelinek, chair of the European Data Protection Board, and Wojciech Wiewiórowski, the European Data Protection supervisor, said: “Deploying remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces means the end of anonymity in those places. Applications such as live facial recognition (LFR) interfere with fundamental rights and freedoms to such an extent that they may call into question the essence of these rights and freedoms.”

Last year, Pope Francis issued a joint statement with IBM and Microsoft calling for curbs on the use of AI with facial recognition systems. And scores of civil rights groups ranging from Amnesty International, Liberty, Big Brother Watch, the Ada Lovelace Institute, and the European Digital Rights network to Privacy International, have launched campaigns to have mass biometric surveillance banned.

So, what is this type of surveillance and why is it so controversial?

First of all, it would be useful to understand the meaning of “biometrics”. These are divided into measurable physiological and behavioural traits. Physiological traits include morphological identifiers such as fingerprints, face shape, vein patterns and so on. They also include biological identifiers such as DNA, blood or saliva. Behavioural measurements include voice recognition, gait, some gestures and even the way you sign your name.

There is nothing new in the use of biometrics in identification: as far back as the second century BC, Babylonian and Chinese rulers used fingerprints on declarations and contracts. In the mid-19th century, hand and fingerprints were used commercially as evidence of agreements, but it was not until 1902 that the first UK criminal conviction was achieved based on fingerprint evidence.

In the 1860s, telegraphy specialists using Morse code were able to name the sender of a message by the unique frequency of their dots and dashes – in much the same way as keystrokes can identify a computer user today. And, remember, even the photograph in your passport is a biometric identifier.

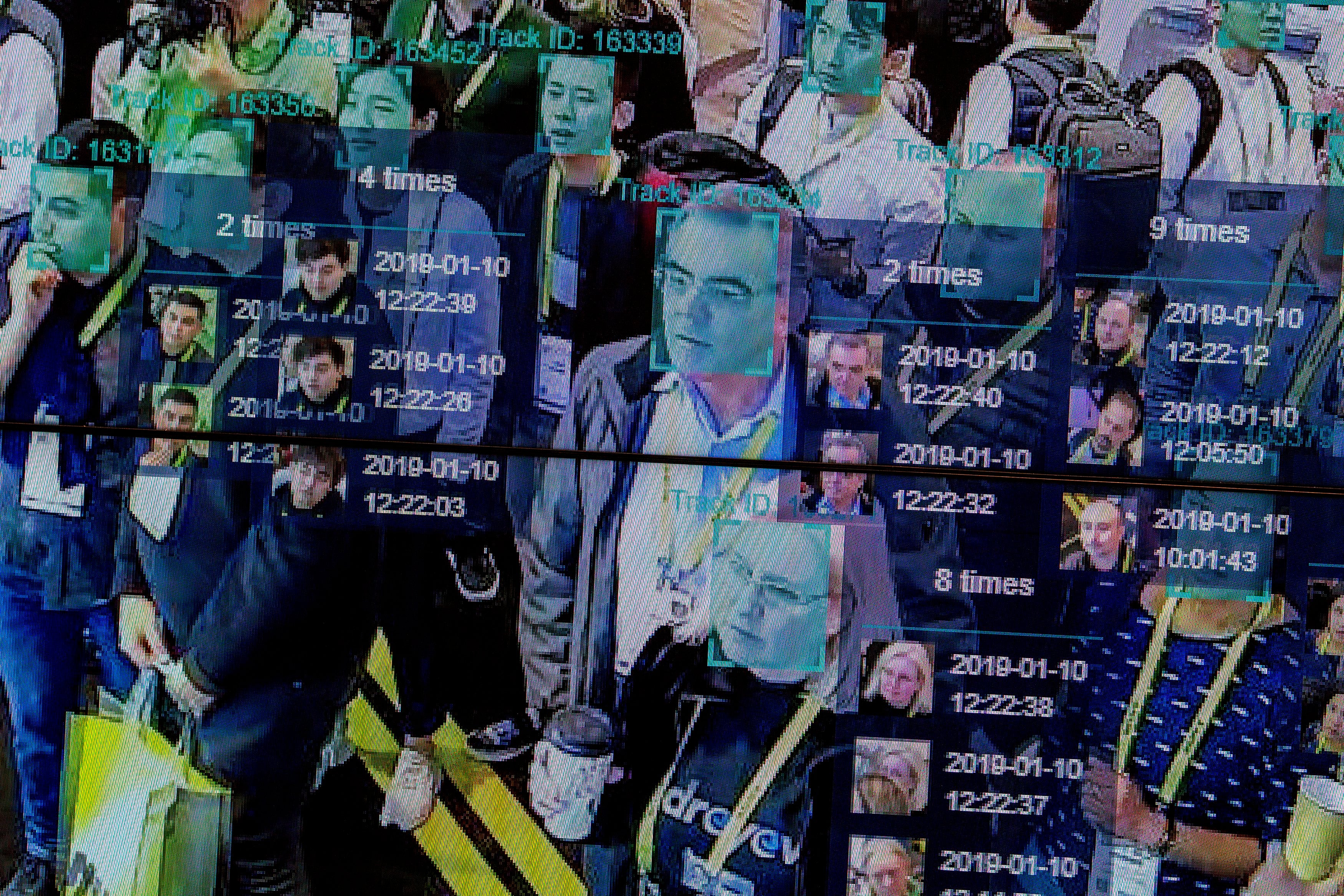

The modern-day difference is that these biometrics can now be produced in digital formats that computers can read at lightning speed and in massive quantities, with AI able to compare them with the contents of databases or “watch lists” before reaching conclusions about the person to whom they belong – ie you.

What privacy campaigners are concerned about is what happens when high-resolution CCTV cameras with facial recognition (or other biometric-identifying) technology and AI capabilities are positioned in public places. They can scan, record and compare the biometrics of all the people who pass by, all the time.

And once these digital identifiers are linked to your name – because over time you will need to use them to gain access to services, to pass through borders, to satisfy financial and economic checks, to prove entitlement to healthcare or benefits and so on – then all your movements, with whom you associate, which demonstrations you attend, which abortion clinic you might visit, which LGBTQ+ bars you frequent, which doctor you have an appointment with, which sex worker you drop in on, or which tryst your spouse doesn’t know about, could be visible to whoever has control of those cameras, be it law enforcement, transport providers, marketeers or the state.

“Not even the Stasi in East Germany or Gaddafi in Libya had access to that much information and power,” says Dr Daragh Murray, senior lecturer at Essex University’s Human Rights Centre and School of Law. “If you were gay in a country where that was illegal, then you’d have to change your behaviour. If you wanted to demonstrate against a totalitarian regime, you could expect to be arrested. If you just wanted to be different, you could face discrimination.

“This kind of technology could mean you’d be tracked and identified everywhere you went, all the time. It would interfere with our right to assembly, our right to privacy and our expectation of anonymity. These systems can even make assumptions about you by the way you behave, your gender, age or ethnicity.”

A recent study by the US video surveillance research firm IPVM found that four Russian-based or backed companies, AxxonSoft, Tevian, VisionLabs and NtechLab, had developed systems able to classify faces on the basis of race. Each of the companies admitted having this capability but responded by saying variously that the ability was an accident or would be removed or was simply not being used.

However, the mere fact of systems being able to focus their attention on certain ethnicities rang alarm bells internationally because AI programmes run on algorithms created by humans, and they are used in conjunction with watchlists and databases also created by humans. And if those humans had prejudices – either conscious or unconscious – then the results could be disastrous.

“The findings underline the ugly racism baked into these systems,” says Edin Omanovic, advocacy director at London-based Privacy International. “Far from being benign security tools which can be abused, such tools are deeply rooted in some of humanity’s most destructive ideas and purpose-made for discrimination.”

Anton Nazarkin, global sales director for VisionLabs, confirmed to me that its system could differentiate between white, black, Indian and Asian, not because it wanted to discriminate between these groupings, but because it had a duty to its customers to be accurate.

Imagine a government tracking everywhere you walked over the past month without your permission or knowledge

However, he said the company had never recorded a single sale of its “ethnicity estimator” function. VisionLabs also says its AI surveillance systems can determine “whether a facial expression corresponds to a broad interpretation of the display of certain emotions”. These are: anger, disgust, fear, happiness, surprise and sadness.

“A lot of stupid questions are asked about facial recognition systems because very few people understand them,” Nazarkin says. “For example, my wife could die this morning, and in the afternoon I might pass by you and smile. This doesn’t mean I’m happy. It just means I smiled at you.

“Journalists keep claiming that the Chinese have systems that can identify if someone is a Uighur in order to discriminate against them. But this isn’t true. What is true is that there are databases containing the identities of Uighurs and these are being used with facial recognition technology.”

This, of course, is a subtle difference. AI and facial recognition don’t see a person as a Uighur, but as a specific person who happens to be a Uighur. But what if, for example, someone is gay in a country where homosexuality is either frowned upon or illegal, and cameras catch them going into a suspected gay bar? A malign state could charge them with an offence; its oppressive apparatus could blackmail them or ruin their professional and personal lives. The same would apply to other “offences” in public, surveilled, spaces.

“Yes,” says Nazarkin, “but traditionally, police have known where such venues are anyway and they used traditional methods to put them under surveillance.”

So, this just makes it easier for them? “Yes,” he replies.

In a now-famous blog post calling for curbs on facial recognition technology in 2018, Microsoft president Brad Smith said: “All tools can be used for good or ill. Even a broom can be used to sweep the floor or hit someone over the head”. So, it is only fair to point out that VisionLabs’ facial recognition technology is being used – in more than 40 countries, according to Nazarkin – to identify online child abusers and to search crowds for dangerous criminals or terrorists with murderous intent.

In his blog, Smith went on: “This technology can catalogue your photos, help reunite families, or potentially be misused and abused by private companies and public authorities alike.

“But other potential applications are more sobering. Imagine a government tracking everywhere you walked over the past month without your permission or knowledge. Imagine a database of everyone who attended a political rally that constitutes the very essence of free speech.

“Imagine the stores of a shopping mall using facial recognition to share information with each other about each shelf that you browse and product you buy, without asking you first. This has long been the stuff of science fiction and popular movies like Minority Report, Enemy of the State and even 1984 – but now it’s on the verge of becoming possible.

“Perhaps as much as any advance, facial recognition raises a critical question: what role do we want this type of technology to play in everyday society?”

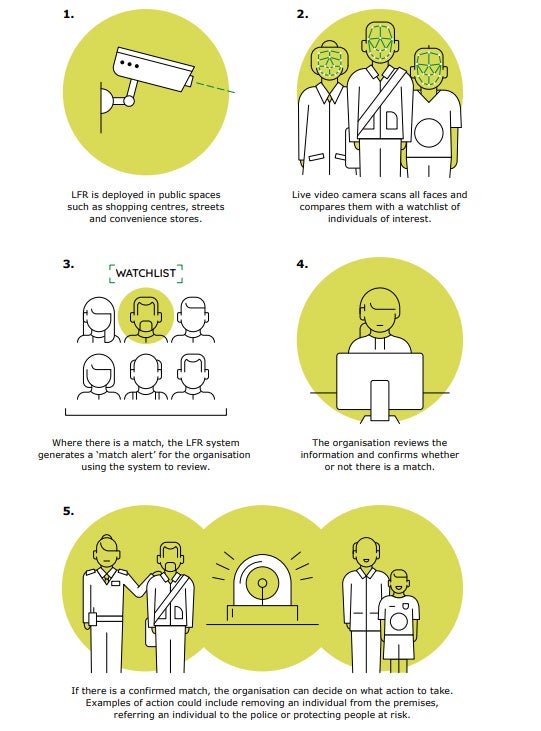

Police forces in the UK are already using LFR systems that can track large numbers of faces in public places and check for people on watch lists in real time. According to the College of Policing, they have been in operation at sporting events, music concerts, public gatherings and – chillingly – protests.

Last year, in a landmark ruling, the Court of Appeal found that South Wales Police had acted unlawfully when it used an LFR system to monitor people and look for suspects in the Cardiff area.

The case was brought by local resident Ed Bridges, 38, who was backed by the civil rights group Liberty. Bridges had argued that his human rights were infringed when his biometric data was analysed without his knowledge or consent while attending an anti-arms protest outside Cardiff’s Motorpoint Arena and while Christmas shopping in the city centre.

However, the court’s ruling wasn’t based on morals or ethics, but simply on the requirement in existing UK data protection law for operators of such systems to clearly document whom they are looking for and what evidence there is that those targets are likely to be in the area. They are also required to thoroughly check that the software being used exhibits no racial or sexual biases, and South Wales Police had failed to adequately do both. But were this police force and others to make more of an effort in these areas, they would be free to use LFR systems.

The judgment was welcomed by both sides, but the losers seemed most pleased with it. South Wales Police Chief Constable Matt Jukes said: “The test of our groundbreaking use of this technology by the courts has been a welcome and important step in its development. I am confident this is a judgment that we can work with.”

Following the ruling, police forces up and down the country began getting their facial recognition ducks in a row to ensure they wouldn’t fall foul of the narrow restrictions that did for South Wales Police. For example, the Metropolitan Police issued a policy document insisting that it would comply with all aspects of common and data protection law.

It said its LFR, known as NeoFace Live Recognition System, would “only keep images that have generated an alert, these are kept for up to 31 days or, if an arrest is made, until any investigation or judicial process is concluded. The biometric data of those who don’t cause an alert is automatically and immediately deleted. The LFR system also records CCTV footage; we keep that footage for up to 31 days.”

Perhaps significantly, the force added: “Anyone can decide not to walk past the LFR system; it’s not an offence or considered ‘obstruction’ to avoid it.” This would suggest that merely walking through the field of view of such a surveillance system would imply consent.

The independent watchdog overseeing police use of this new surveillance technology is Professor Fraser Sampson, the biometrics and surveillance camera commissioner, a hugely capable former police officer and lawyer who is trying to do his job with one hand tied behind his back. As biometrics commissioner, his task is to monitor the way the police take, store and delete DNA and fingerprint evidence. But the police’s new desire for ever-growing biometric databases against which to check surveillance images has given him a fresh problem.

“Police forces have a huge number of images of suspects taken on arrest who were never charged,” he tells me. “There is legislation to govern what happens to the DNA and fingerprints of these people – even prints taken from the soles of their shoes – but, bizarrely, there is none on the deletion of facial images.

“Images are not officially part of my remit but I have been asking forces what policies they have in place for automatically deleting them or alerting the public to the fact that they can ask for them to be deleted, and I’m finding that there is no ubiquitous policy. Historically there’s been an approach in policing that just inadvertently not getting round to deletion is seen or has been seen as a sort of a neutral act, whereas in fact, it isn’t – it is a retention.

“So, if police force X decided to digitise old photographs [mugshots of people who were never charged], and then they had surveillance cameras with facial recognition in town centres, could it be the case that these flag up people who were wanted for certain crimes?”

Sampson has asked ministers to move quickly to bring his responsibilities and powers up to date. His role as biometrics commissioner was framed by the Protection of Freedoms Act 2012; his second role, as surveillance camera commissioner, was defined by the Surveillance Camera Code in 2013. At the time, CCTV had no digital biometric AI facial recognition capabilities.

The call for a ban on the use of AI and mass facial recognition issued by the European data protection board and the European data protection supervisor came as part of a consultation process being undertaken by the European Commission following the release of its draft Artificial Intelligence Act in April.

If enacted, the act would apply to any company or entity that wanted to operate in, or trade with, the EU. It would ban the use of any AI that:

- Used subliminal techniques to manipulate a person’s behaviour in a manner that may cause psychological or physical harm.

- Exploited vulnerabilities of any group of people due to their age, physical or mental disability in a manner that may cause psychological or physical harm.

- Enabled governments to use general-purpose “social credit scoring”.

- Provided real-time remote biometric identification in publicly accessible spaces by law enforcement except in certain time-limited public safety scenarios.

Already, privacy campaigners argue that it has not gone far enough, as the draft proposals don’t ban all mass public surveillance but define such surveillance as “high risk”, meaning it would be allowed subject to stricter controls than other, more benign, forms of AI with biometric identification (such as knowingly using your biometrics to pass through a border, prove who you are and so on).

Anyone can decide not to walk past the LFR system; it’s not an offence or considered ‘obstruction’ to avoid it

Wiewiórowski, the European data protection supervisor, told me his joint protest with the European data protection board was made as part of the consultation process – and this is likely to rumble on for many months.

“Our statement wasn’t about the technology itself and the innovations it might lead to,” he said. “We made it because we would be very, very cautious with using [AI mass biometric surveillance] in the public space at places where people are not aware of the fact that they are being observed, surveilled and recognised. That could lead to the final loss of privacy and anonymity on the streets.

“We believe we should start with the ban and then think about exceptions, to precisely write down what all the purposes it could be used for and which are exceptional situations in which it might be appropriate.”

Wiewiórowski, who is Polish, pointed to recent demonstrations by judges in Poland over proposed changes to the judicial system, arguing that a future mass ID surveillance could have identified lawyers and led to their dismissal. Similarly, Chinese use of such systems were leading to the collapse of open defiance by opposition groups in Hong Kong, he said.

Wiewiórowski expressed disappointment that an official opinion published in June on the use of LFR by Elizabeth Denham, the UK’s Information Commissioner (its data protection watchdog), had not echoed his call for a moratorium on its use.

Her opinion argued that any entity wanting to use LFR in the UK had to comply with provisions in the 2018 Data Protection Act and the UK General Data Protection Regulation, which, for now, is the same as the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation. These provide for lawfulness, fairness, transparency, purpose limitation, data minimisation, storage limitation, security and accountability.

The opinion says: “Organisations will need to demonstrate high standards of governance and accountability from the outset, including being able to justify that the use of LFR is fair, necessary and proportionate in each specific context in which it is deployed. They need to demonstrate that less intrusive techniques won’t work. These are important standards that require robust assessment.

“Organisations will also need to understand and assess the risks of using a potentially intrusive technology and its impact on people’s privacy and their lives. For example, how issues around accuracy and bias could lead to misidentification and the damage or detriment that comes with that.”

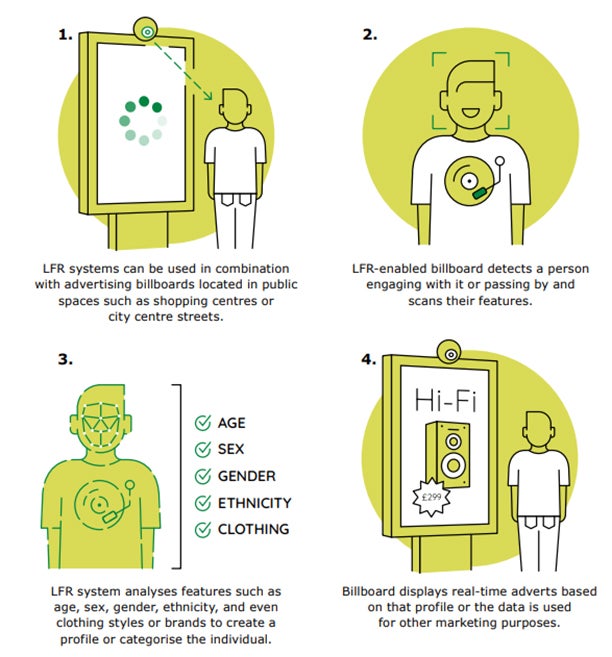

However, in a blog post released to coincide with the opinion, Denham openly expressed fears over the way the technology could be misused, and she questioned the usefulness of LFR systems that her department had studied. “I am deeply concerned about the potential for LFR technology to be used inappropriately, excessively or even recklessly,” she wrote. “When sensitive personal data is collected on a mass scale without people’s knowledge, choice or control, the impacts could be significant.

“Uses we’ve seen included addressing public safety concerns and creating biometric profiles to target people with personalised advertising.

“It is telling that none of the organisations involved in our investigations were able to fully justify the processing and, of those systems that went live, none were fully compliant with the requirements of data protection law. All of the organisations chose to stop, or not proceed with, the use of LFR.

“Unlike CCTV, LFR and its algorithms can automatically identify who you are and infer sensitive details about you. It can be used to instantly profile you to serve up personalised adverts or match your image against known shoplifters as you do your weekly grocery shop.

“In future, there’s the potential to overlay CCTV cameras with LFR, and even to combine it with social media data or other ‘Big Data’ systems – LFR is supercharged CCTV.”

So, if she is so concerned about live facial recognition systems, I asked Denham why she hadn’t followed her European counterparts in calling for a moratorium on their use? She replied: “It’s not the role of the Information Commissioner’s Office to endorse or ban new technologies. But, like others, we recognise the importance of this issue and the protections which must be in place before LFR technology advances unchecked and public trust and confidence is damaged.

“The ICO’s primary responsibility is to ensure compliance with data protection law to protect the public. We provide guidance to help organisations and companies get it right, and we explain how the law applies to the use of personal information in different scenarios … Where the legal standards are not met, we have the ability to enforce the law.”

The timing of Denham’s warning is significant. In a Union Jack-emblazoned report issued in May by the government’s Taskforce on Innovation, Growth and Regulatory Reform headed by staunch Brexiteer Sir Iain Duncan Smith, your personal data is not seen as something that should be protected, but as a resource to be exploited.

The report recommends tearing up the protections afforded citizens under GDPR – such as you having to consent to having your personal information shared – and replacing them with a new framework that allows data to “flow more freely”.

The report makes no attempt to hide the government’s intention to do away with your rights in the name of corporate profit. It says: “Consumer data is highly profitable and a currency in itself. It’s hard to pinpoint the exact value of consumers’ data – one study estimates the email address of a single internet user to be worth $89 and the total data of the average US resident $2,000 – $3,000.

EU citizens are more likely to have more protections over the misuse of mass facial and other biometric recognition systems than we are in the UK

“There is a multibillion-dollar industry of data brokers – companies that collect consumer data and sell it to other companies. Studies show that on average Google holds the equivalent of roughly 3 million Word document pages per user in personal data and Facebook holds around 400,000 pages of data per user.

“GDPR is prescriptive, and inflexible and particularly onerous for smaller companies and charities to operate. It is challenging for organisations to implement the necessary processes to manage the sheer amounts of data that are collected, stored and need to be tracked from creation to deletion. Compliance obligations should be more proportionate, with fewer obligations and lower compliance burdens on charities, SMEs and voluntary organisations. Reforming GDPR could accelerate growth in the digital economy, and improve productivity and people’s lives by freeing them up from onerous compliance requirements.

“GDPR is centred around the principle of citizen-owned data and organisations generally needing a person’s ‘consent’ to process their data. There are alternative ways to process data that do not require consent…”

For now, this is where we are. We have police forces planning to hoover up the biometrics of innocent people in the street without their knowledge or approval, and we have a government that finds the idea of consenting to share private data an inconvenience at best, an irritant at worst.

EU citizens are more likely to have more protections over the misuse of mass facial and other biometric recognition systems than we are in the UK – though if we want to maintain any kind of data-sharing relationship with the EU we might have to embrace its rules on the use of artificial intelligence and biometrics at some point in the future.

If that were to happen, you (but probably not Iain Duncan Smith) would have the faceless bureaucrats of the European Commission to thank for drafting the legislation that could save us from the worst excesses of facial recognition surveillance in the UK.

And if that weren’t so sad, it would be funny.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks