Can Bilbao’s Guggenheim provide a model of art-led levelling up?

William Cook finds out that a once-controversial museum has been at the centre of the rejuvenation of the Basque city

Outside Bilbao’s Guggenheim Museum, beside the Río Nervión, stand two sculptures by Eduardo Chillida, the Basque Country’s greatest modern artist, which symbolise the rejuvenation of this gutsy Spanish port. These robust iron monoliths reflect Bilbao’s rustbelt origins, a city built on shipbuilding and steelmaking, and its dramatic shift to service industries, clean energy and research.

Art has played a leading role in Bilbao’s revival, and the Guggenheim Museum has been centre stage throughout this process. Twenty-five years since it opened, Bilbao is inconceivable without it. So how did an art gallery act as a spur for urban regeneration – not just as a cultural catalyst, but as an economic driver too? As the Guggenheim celebrates its silver jubilee, what can other cities learn from what’s become commonly known as the “Bilbao Effect”?

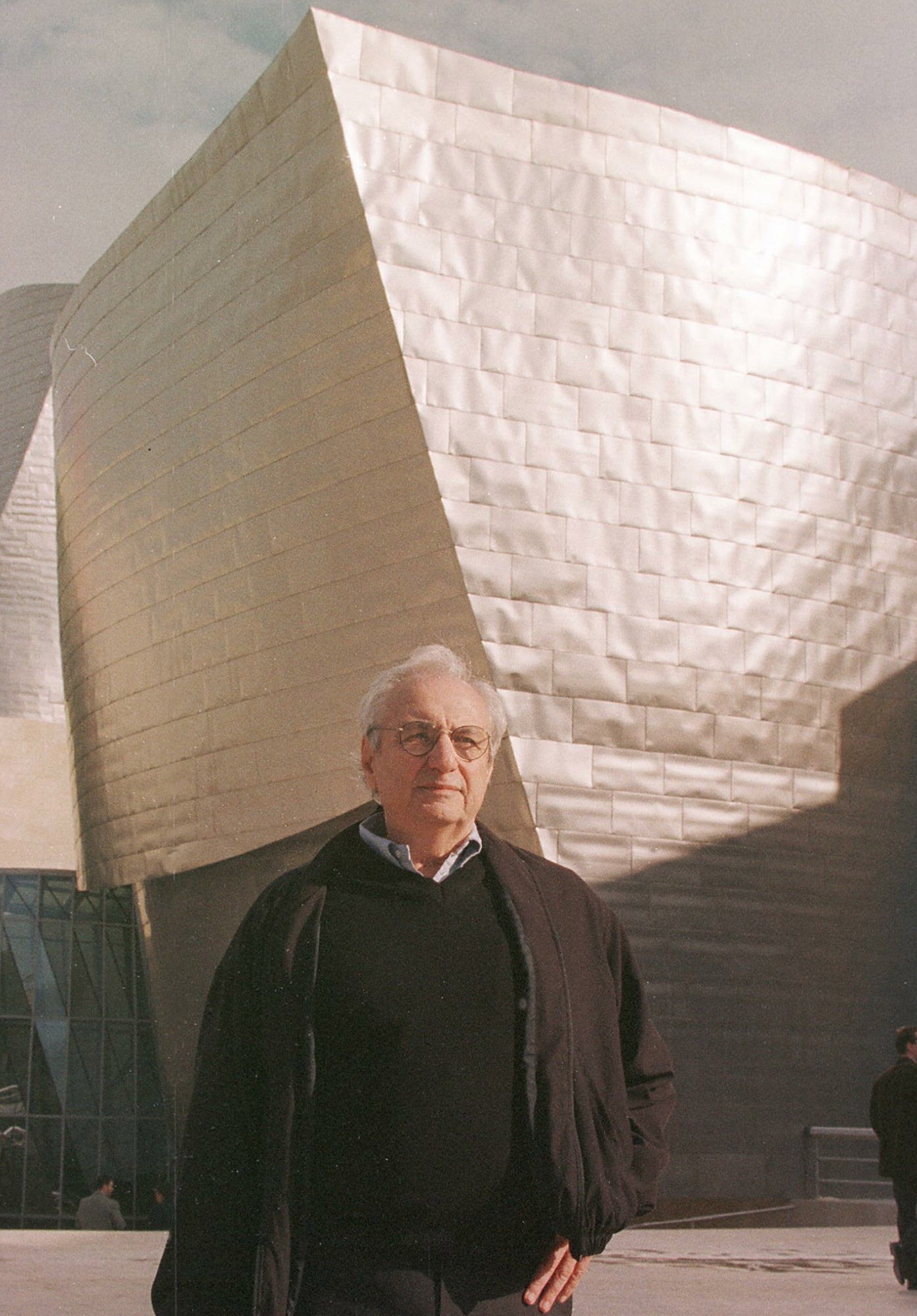

Designed by American starchitect Frank Gehry, in an old dockland site on the waterfront, the Guggenheim is an extraordinary building. Photographs don’t do it justice – you have to see it for yourself. A twisted mass of gleaming metal, more like sculpture than architecture, it’s an artwork on a massive scale. One of the world’s most iconic buildings like the Eiffel Tower. Yet, like the Eiffel Tower, its construction was extremely contentious – looking back, it seems remarkable that it was ever built at all.

Bilbao’s recent renaissance is evident throughout the city. The shops and cafes are busy, the apartment blocks are spic and span, and the old docklands have become new parklands. Yet 30 years ago, when the Guggenheim was first conceived, Bilbao was a very different city from today. The streets were drab and dirty, and the river was filthy. Historically, the city had derived its wealth from mining the rich iron ore in the surrounding hills, which fed its steelmaking and shipbuilding, but now those industries were dying. Bilbao had to start again.

The city hit rock bottom in 1983, when the centre was devastated by massive floods. “It was a watershed moment,” says Juan Ignacio Vidarte, the director of the Guggenheim. “That was probably the moment when the city started to think it had to change.” The Guggenheim was a big part of this change, but it wasn’t the only part. The museum was just one element in a coordinated programme, designed to turn Bilbao around.

“If you want to have an overall effect, the project needs to be part of a broader strategy,” explains Vidarte, sitting in his sunlit office in the Guggenheim, looking out across the river. “It needs to be consistent with an overall plan.” This plan focused on three key factors: culture, infrastructure and the environment. This is now a familiar model, but back then it was something new.

Bilbao’s economic problems were pan-European problems, and there were no easy answers. Left-wing governments had tried to protect jobs by propping up traditional industries; right-wing governments had cut public subsidies and left these industries to sink or swim. However, even for politicians who regarded public investment as essential, forking out for a flamboyant new gallery seemed like a reckless extravagance. The Guggenheim cost €86m to build, with another €36m earmarked for new artworks. Wouldn’t it be better to spend the money on schools or hospitals instead?

“It was a very controversial project – there was a lot of opposition,” says Vidarte. “‘Why don’t you spend this money helping some of those failing industries?’ Even in the Basque cultural sector, there was a lot of concern and criticism: ‘Why are you spending this money on a foreign institution?’” In those days a lot of people didn’t see the Guggenheim as an investment. They saw money spent on culture as pure expenditure, with no long-term return.

Building the Guggenheim wasn’t a shot in the dark, Vidarte’s colleagues made sure they did their homework. In 1991, before the decision was made to proceed, a feasibility study showed the museum would have a dynamic impact on the local economy. At the time, the study was criticised for being too optimistic. It turned out to be an underestimate. “We have had more visitors than expected and that means the economic impact has been much bigger than what was expected.”

Nevertheless, the Guggenheim was still a gamble, especially as the political situation in Bilbao was so precarious. Bilbao’s post-industrial headaches were replicated throughout Europe, but it also had a particular problem to contend with, which exacerbated its economic woes. Since the late 60s, the Spanish government had been grappling with the Basque separatist movement Euskadi Ta Askatasuna, known as ETA. Hundreds of people had been killed.

An expensive, high-profile project in the biggest city in the Basque Country, the Guggenheim became a target for ETA activity. A week before the new museum opened, in 1997, a police officer was shot and killed when he apprehended ETA terrorists disguised as gardeners, as they attempted to plant remote-controlled grenades inside a floral sculpture by Jeff Koons (which still stands outside the museum). “We were still living in a situation of political violence,” says Vidarte, gravely. “Fortunately, we also lived in a situation where the process started to change. I would like to think that we have been part of that process.”

In spite of all these obstacles, the Guggenheim has been a great success, attracting around a million visitors per year – more than twice the number the museum initially anticipated. Around 60 per cent of these visitors are from abroad, and they don’t just spend money in the museum. They take taxis, they go shopping, they stay in hotels and eat in restaurants, in Bilbao and beyond.

The museum’s €122m start-up cost has been dwarfed by an income of around €235m per year, plus a further annual expenditure of around €260m in the Basque Country as a whole. Directly and indirectly, the museum has created over 5,000 new jobs, raising nearly €500m a year for the region. “Our yearly budget is about €29m, of which about a third comes from public subsidies,” says Vidarte. “In terms of taxes, that generates €70m a year.”

So if you’re the mayor of a struggling city with a shrinking tax base and a redundant workforce, do you simply commission a famous architect to build a swanky gallery and wait for the revenue to flood in? If only it were that easy. The Guggenheim hogs the headlines, but it never would have worked in isolation. It was one part of a comprehensive plan, spanning ecology and public transport. Bilbao spent hundreds of millions of euros cleaning up the previously polluted river. It built a new airport, designed by leading Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava. It built a new metro, connecting the city centre with its suburban hinterland.

Bilbao’s metro was designed by Britain’s greatest living architect, Sir Norman Foster, who fell in love with Bilbao while he was working here. “Of all my memories as an architect,” said Foster, “nothing compares with my experience in Bilbao. There was something almost religious about that experience and I’ll never forget it.” Bilbao loves him back. His elegant metro entrances, which look a lot like seashells, are nicknamed Fosteritos in his honour.

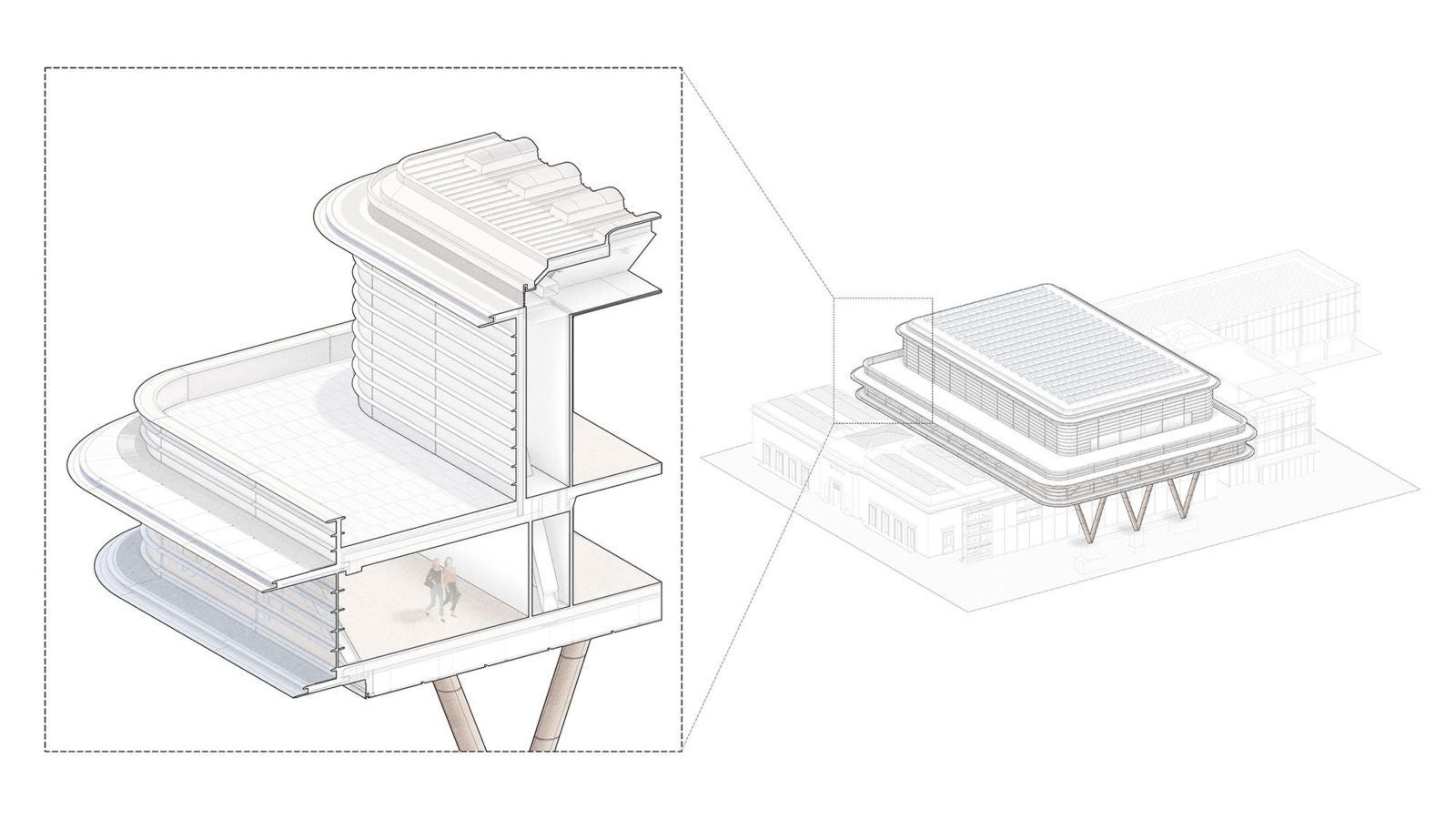

Now Foster is back in Bilbao, designing a new extension to the Museum of Fine Arts. Like his redesign of Berlin’s Reichstag, it promises to re-energise a historic building, by adding a new cupola and revitalising the existing space. Led by Gehry’s Guggenheim, the city has become a forum for the world’s best architects, such as Arata Isozaki and César Pelli.

“Twenty-five years ago, there was no cultural tourism in Bilbao,” says Miguel Zugaza, director of Bilbao’s Museum of Fine Arts. “Now, 50 per cent of the people that visit our museum come from other cities or other countries.” The Museum of Fine Arts benefited immensely from the popularity of the Guggenheim, a short walk away, but Zugaza also stresses the importance of the new metro and cleaning up the river. “They are fundamental to understanding the transformation of the city.“

For industrial cities in other countries, the lessons are clear: landmark buildings are no use unless you also make a city attractive and connected. “I think that many industrial cities, in their own transformation, can take some examples of our transformation – and maybe they can apply them in their own cities,” says Zugaza, as he shows me the plans for Foster’s ambitious extension.

Culture, public transportation and the environment are all paramount in this transformation, but Bilbao has also been supported by its political institutions, both regional and international. Spain’s entry into the EU was a big factor in Bilbao’s reinvention as a hi-tech hub. Previously a provincial city on the periphery of Spain, Bilbao is now intimately connected with the whole of Europe. Joining Schengen and then the Euro brought other EU member states even closer. Today, nearly one in five visitors to the Guggenheim come from France, and no wonder. Travelling here from France (or other EU countries) is just as easy as coming here from elsewhere in Spain.

Devolution is another core part of the package. The Basque Country collects and allocates its own taxes, only outsourcing international matters like defence and foreign policy to the national government in Madrid. Local politicians have the power to make big decisions; taxpayers in Bilbao can see a clear connection between the taxes they pay and the money spent on public projects.

“Without our political and economic model, all this transformation would not have been possible,” says Zugaza. “It’s not something ideological – it’s something real. You have the tools in your hands to do this.”

And the benefits go way beyond the ability to build new museums and galleries, or even metro stations. Franco tried to eradicate the Basque identity, but its sense of nationhood is now restored. ETA declared a ceasefire in 2010, disarmed in 2017, and dissolved in 2018.

My final appointment in Bilbao was at Azkuna Zentroa, the city’s spectacular centre of contemporary culture. An audacious conversion of an old wine warehouse, designed by Philippe Starck, it’s a stunning building, inside and out, but what’s most impressive is how well it works as a shared space for every kind of cultural activity, from fine art to sport. There’s a library, a gym, a cinema and a rooftop swimming pool – all within the same building. Gehry’s Guggenheim is the big attraction that draws new visitors to Bilbao, but the Azkuna is a cornerstone of daily life, a place where locals can meet up and hang out.

“Culture and art integrate through people,” says Azkuna’s director, Fernando Pérez. “The rehabilitation of this centre by Philippe Starck is along the same lines as the Guggenheim – the same strategy, to turn industrial areas of Bilbao that have been in deep decay into something of value.”

Like the Guggenheim, Azkuna Zentroa isn’t merely about spending public money – it’s about making money too. “For each Euro, this centre returns double,” he tells me. “It has revitalised the whole region.” From retail to real estate, the entire area has seen an upturn. Surrounding streets have been pedestrianised, making this former industrial district a pleasant place to live and work. “Short-term policies do not work,” says Pérez. “In the next crisis, you’re going to find yourself in the same pit.”

Pérez grew up on the left bank of the Río Nervión, the industrial heartland of Bilbao. When he was a child, Bilbao was a grey city and there were frequent strikes and angry clashes between the strikers and the police. However, there were also intrinsic elements within this society which facilitated Bilbao’s comeback. “We were brought up to think that hard work was an asset.”

Like the Guggenheim, the Azkuna Zentroa opened in an era when ETA was still active. “There was still violence, times of turmoil and political difficulty – but perhaps because of that, culture was the only way. Because it was so difficult politically, the only way forward was through culture.” The inclusive success of Azkuna proves culture needn’t be passive or elitist. “The citizens are not just recipients of art – they are also creators of it.” People don’t just come here to gaze at artworks. They come to make art, too.

Back on the waterfront, the Guggenheim Museum is full of people. To celebrate the museum’s 25th anniversary, for the next few weeks anyone from the Basque Country gets free admission, and the place is crowded with locals, looking at the artworks, and soaking up the ambience. Like all the best cultural institutions, Gehry’s building has become a rendezvous. From the top floor, you get a great view over the river toward the green hills beyond.

There’s a lot more to Bilbao than the Guggenheim, but every city needs an icon, and in our current cost-of-living crisis this building is a powerful reminder that art can pay its way and more. “It’s not the most important investment by far, and it’s not the only one for sure, but I think it’s been a crucial element of that transformation,” says Vidarte. “This project, I think, is a symbol, of how you can confront a tough period and try to make the future better.”

In our era of empty sloganeering, Bilbao’s investment in culture, infrastructure and ecology is a prime example of what “levelling up” really means.

For details about art and culture in Bilbao, visit www.guggenheim-bilbao.eus, www.bilbaomuseoa.eus or www.azkunazentroa.eus

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks