How a Swiss city the size of Peterborough conquered the art world

William Cook on the story of a trailblazing Swiss couple who shunned the bright lights of New York and Paris to build a museum full of masterpieces in Basel... making it home to the most prestigious art festival on the planet

In a quiet side street in Basel, on a steep hill above the River Rhine, stands a building that reveals the vast artistic clout of this unassuming Swiss city. At first glance, it doesn’t look like much – a discreet and tidy townhouse, a lot like the other tidy townhouses all around it – but for 65 years it housed a remarkable gallery, run by a remarkable Swiss couple called Ernst and Hildy Beyeler.

Ernst Beyeler was one of the world’s great art dealers, and in 1970 he co-founded an art fair called Art Basel, now widely regarded as the most important art fair in the world. During this year’s fair, more than 200 of the world’s top galleries will descend upon this compact city, showing and selling works by thousands of leading modern artists. However, Art Basel has never been just about the numbers. Quality not quantity has always been its watchword, and this has made it the gold standard of the commercial art scene.

I drop into Galerie Knoell, a chic commercial gallery around the corner from Ernst Beyeler’s old HQ. It’s run by a dynamic young gallerist called Carlo Knoell. This year, he’s exhibiting at Art Basel for the first time. So how important is Art Basel, I ask him. “If you compare it with football,” he tells me, “it’s the Champions League.”

A lot of art fairs happen behind closed doors, hidden from the hoi polloi. Not in Basel. Art Basel is more of a festival than a trade fair, with events all over town: sculptures sprout up in its streets and parks; its many excellent museums (37, last time I counted) mount a range of superb shows. In a metropolis like London or Paris or New York, this would still be exceptional, but Basel has a mere 175,000 inhabitants, about the same size as Peterborough. So how did such a small city become such a big hitter in the art world?

The foundation of Basel’s artistic success is its age-old internationalism. More than any other Swiss city, it’s always been closely connected with the wider world. The French and German borders are both just a few miles from the city centre, but its biggest asset has always been its key position on the River Rhine. Before railways and motorways, this mighty river was Europe’s main thoroughfare, and the constant flow of foreign traffic opened up Basel to new ideas.

Like other medieval ports along the Rhine, Basel attracted the cream of European intelligentsia. However, unlike other Rhineland ports, Basel was a fledgling democracy rather than a royal fiefdom, so its intellectual immigrants were more inclined to stick around. Most notable among them was Erasmus of Rotterdam, who published many of his books in Basel (he’s buried in Basel’s imposing Minster, a stone’s throw from Beyeler’s old gallery).

The finest philosopher of his age, Erasmus personified Basel’s progressive outlook, and his liberal ideas had a lasting influence on the city’s attitude to the arts. His portrait (painted by Hans Holbein) hangs in Basel’s Kunstmuseum, a gallery that demonstrates Basel’s deep artistic roots. Incredibly, this municipal museum dates all the way back to 1671, when Basel’s city fathers decided to open the city art collection to the public, making the Kunstmuseum Europe’s oldest public art museum.

“It goes all the way back to the Renaissance, because here we had early book printing and paper mills, and therefore we had early scholarship and universities, and that was the basis for the arts,” explains Anita Haldemann, deputy director of the Kunstmuseum, and its head of Art & Research. “Those are the ingredients you need for a culture to develop and blossom – you need people who cherish it, support it, buy it and collect it.” Over subsequent centuries those complementary elements came together in Basel.

The calamities of the first half of the 20th century cemented Basel’s position as a safe haven for art and artists. Due to its neutrality in both world wars, a lot of foreign art and foreign money ended up in Switzerland. After the Second World War, Eastern Europe was shut off behind the iron curtain and much of Western Europe was destroyed. Bordering both France and Germany, but untouched by the turmoil of the Second World War, Basel became an ideal location for continental art dealers and collectors to do business.

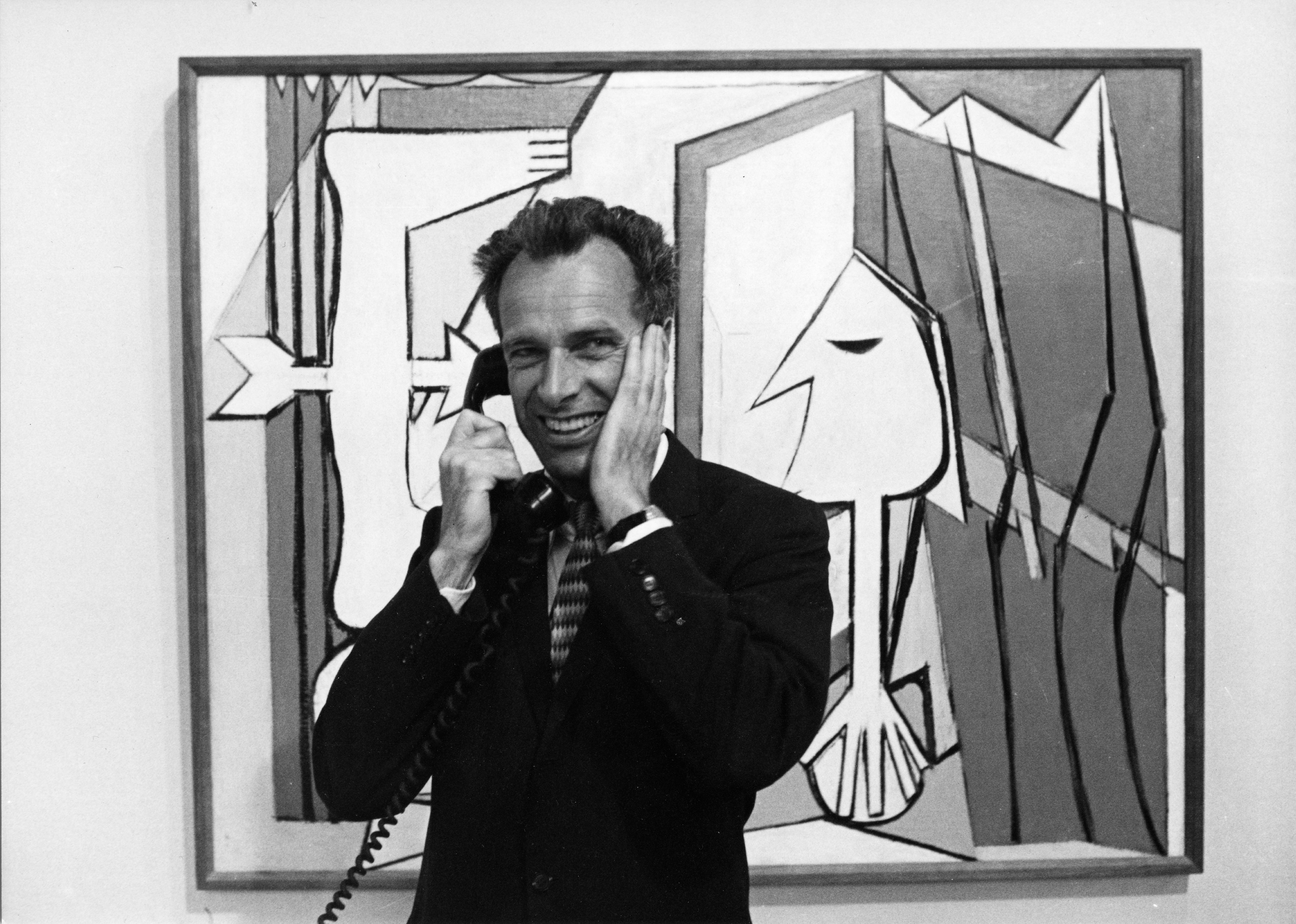

Looking back, it’s clear that Ernst Beyeler was in the right place at the right time, but even so his gallery was an incredible achievement. During the war it had been an antiquarian bookshop, where Beyeler worked part-time. In 1945, he got the chance to take it on and turn it into a gallery. He was still only in his early twenties, with no money, training or experience, but he was shrewd, honest and hardworking, and he had a great eye for art.

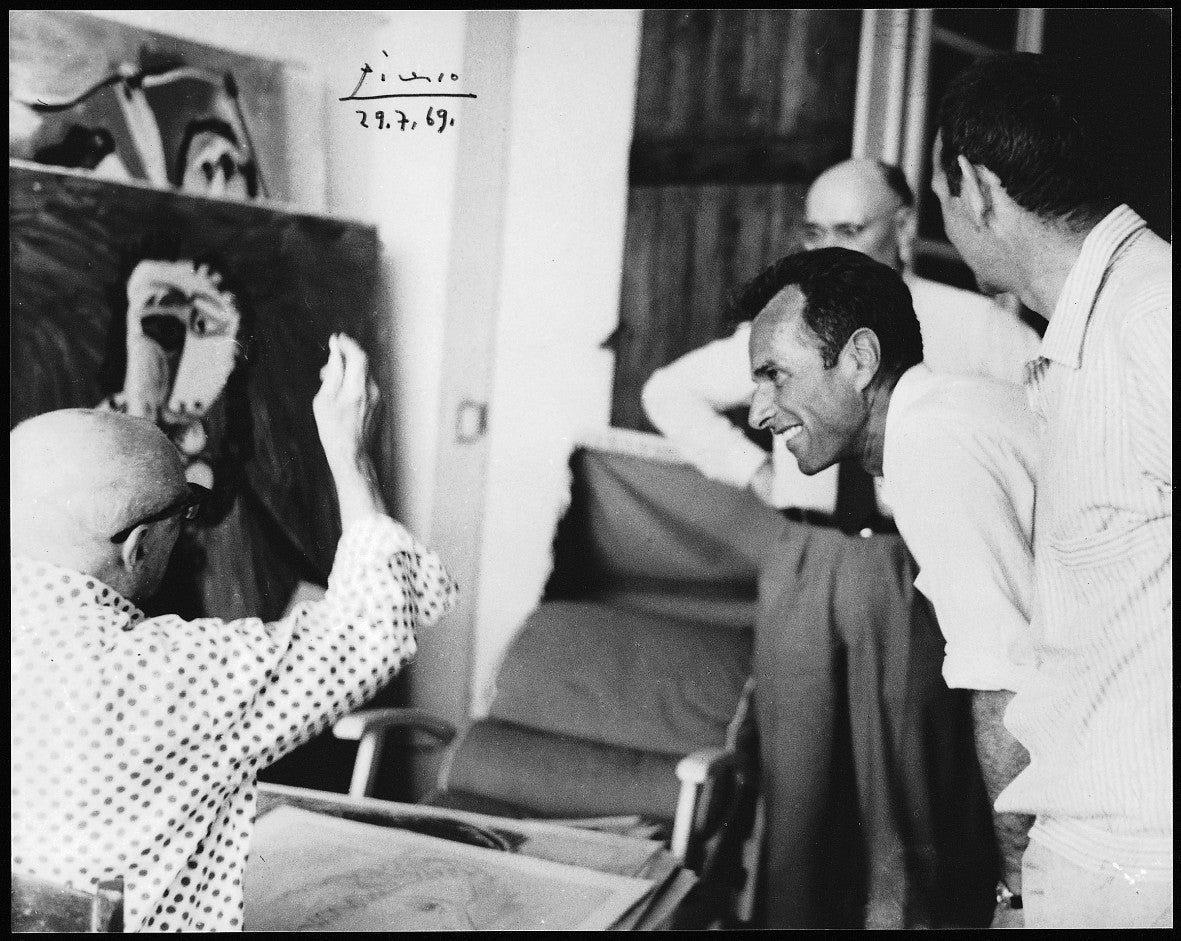

How did he choose which works to buy? “I have to feel fascination,” he told Christophe Mory, the author of an absorbing book about Beyeler, A Passion for Art. “My eyes, my mind and my whole body have to be caught up in the experience.” Beyeler was a self-taught, self-made man, without specialist qualifications, but when it came to buying and selling art, this proved an advantage, not a disadvantage. “I leave commentaries to academics and art historians,” he said. “I have no preconceived notions.” Collectors liked and trusted him. He befriended many of the world’s great artists: Pablo Picasso, Alberto Giacometti, Mark Rothko, Jean Dubuffet...

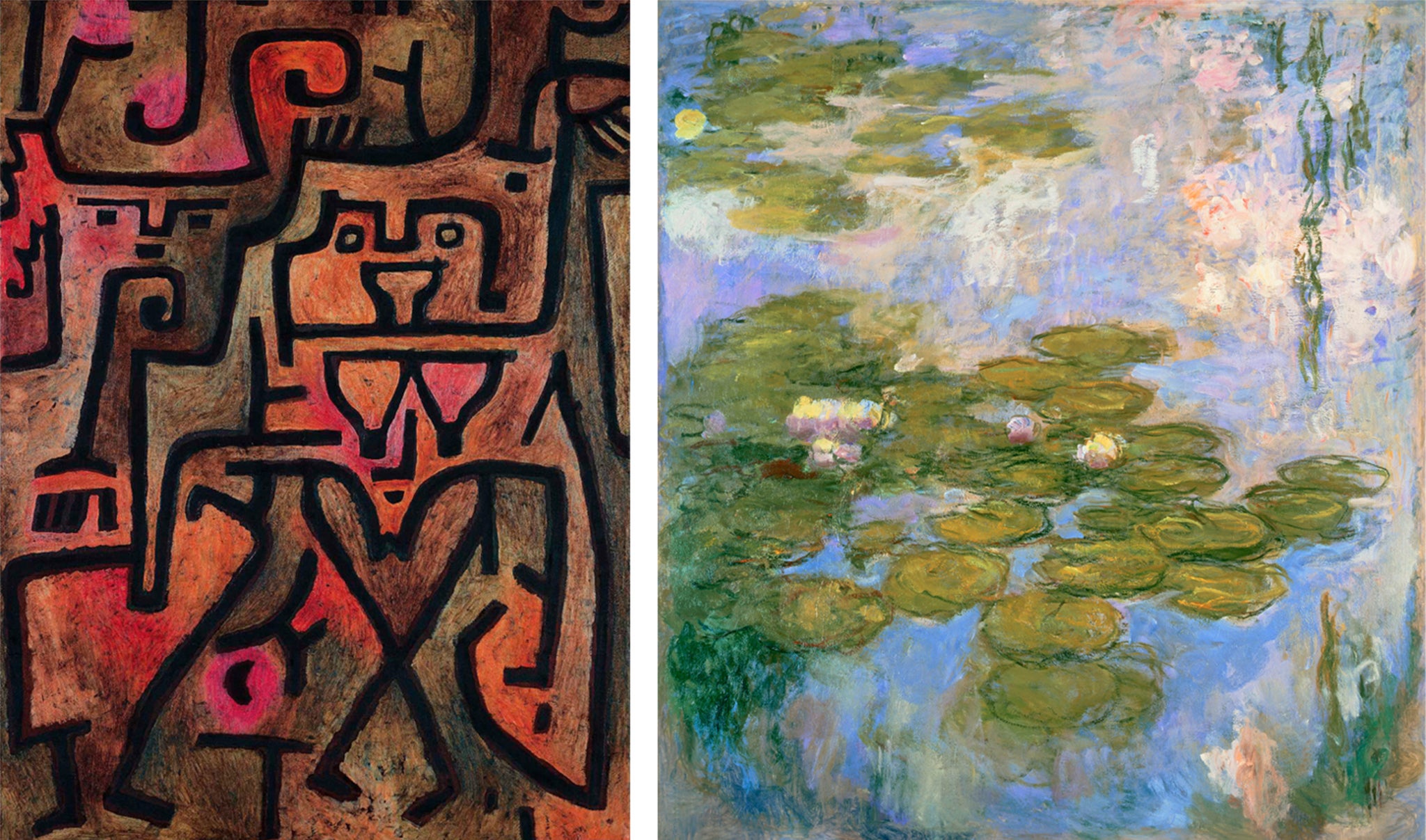

Beyeler didn’t discover unknown artists. He didn’t see himself as a pioneer. He simply bought and sold the very best works by the very best “classic modern” painters, from Impressionism to Pop Art, from Monet to Warhol. It was a winning formula. “What is Beyeler buying?” became a buzzword in the industry. The business thrived, allowing him to build up an amazing collection of his own.

Beyeler could have relocated to New York, to hobnob with the world’s richest collectors. He did a lot of business in America, but he decided to stay put in Basel. He loved its humanist heritage, its annual carnival. He admired the wit, the invention, the imagination of its citizens. A smaller city like Basel is great for networking – more intimate, more personal. Contacts congregate in the same bars and restaurants. The city centre is entirely walkable. You bump into colleagues on the street.

Beyeler’s loyalty to Basel was vindicated in 1967 when a rich patron of the Kunstmuseum was compelled to sell two Picassos which had been on long-term loan to the gallery. To prevent them being sold abroad, the city would have to buy them. Locals campaigned to keep them, raising several million Swiss francs in the process. Picasso was so moved that he gave the Kunstmuseum four more of his paintings to hang alongside them.

Beyeler and his colleagues realised that an art fair would generate more interest than a gallery ever could, and with so many inhabitants who shared Beyeler’s passion for modern art, it’s no surprise that Art Basel (confined to artworks from 1900 onwards) was successful from the start. The inaugural fair, with 90 galleries, attracted more than 16,000 visitors. Its range was transatlantic – not just European galleries, but American galleries too. Art Basel wasn’t the first European art fair – Art Cologne, in Germany, is the oldest, dating back to 1967 – but it soon established its own identity. As Anita Haldemann says: “It really put the city on the international map.”

“It was absolutely the place to be,” says the eminent Austrian gallerist, Thaddaeus Ropac, who’s been exhibiting at Art Basel since the 1980s. “It was a big step; it was an important step.” To be accepted was an honour. “It was always difficult to get in.” Because the entry requirements are so high, buyers are reassured. “What I see there, first of all, I can be sure it’s real – it’s not a fake. And secondly, I can assume it has a certain quality – otherwise it would not be allowed to show there.” “They have a very, very rigorous selection committee,” confirms Rachel Lehmann, who’s one half of the renowned commercial gallery, Lehmann Maupin.

More than half a century since then, Art Basel has never stopped innovating, and that’s been central to its staying power. In the 1980s, it became a pioneering promoter of art photography. During the 1990s it branched out into film and video. In 2002, it launched Art Basel Miami Beach, an audacious invasion of America. “It was unheard of,” says Ropac. “It was a very bold move.”

“It was a very exotic idea,” says Lehmann. “It didn’t make sense, in a way.” But she soon realised it was a brilliant innovation. The first art fair in Florida attracted 160 galleries from 23 countries, and 30,000 visitors. Now an annual institution, Art Basel Miami Beach has gone from strength to strength.

Art Basel Hong Kong followed suit, the first Western art fair to go to Asia. Most remarkably of all, last year Art Basel pitched up in Paris, the historic centre of the art world (Paris + par Art Basel will be back again this autumn). When Art Basel began, the art world was largely confined to Western Europe and North America. It’s since expanded worldwide, and Art Basel has expanded with it. As Noah Horowitz, CEO of Art Basel, explains to me: “The story of Art Basel is very much a story of the emergence of the contemporary art market, writ large.” Art Basel has become a global brand with global recognition. James Koch, executive director of illustrious Swiss gallerists Hauser & Wirth, calls it “the most important week in the art world calendar”.

In 1997, Ernst and Hildy Beyeler added another dimension to the Basel art scene with the opening of Fondation Beyeler, a large and graceful gallery in a lush garden on the green edge of town, which they built to house their personal art collection. The contents are astonishing, one of the world’s best private collections of modern art, supplemented by world-class exhibitions. The building, by Italian starchitect Renzo Piano, is an artwork in its own right, a serene and peaceful space flooded with natural light.

Hildy died in 2008 and Ernst in 2010, and this building is their monument. “They had offers from all over the world, to have museum wings built for them in cities, but they wanted to have the museum in the landscape – embedded in landscape here on the outskirts of Basel,” says Sam Keller, the director of Fondation Beyeler, and the director of Art Basel from 2000 to 2007. Ernst Beyeler started his career six thousand Swiss francs in debt. He left us Switzerland’s most visited art gallery, a museum full of 20th century masterpieces that attracts several hundred thousand art lovers every year.

“He was a man of incredible curiosity, and of great courage and ambition,” says Keller. “He could easily have gone to London or New York or Paris, the really important art centres, but he believed that Basel was in fact an interesting art city.” Indeed it was – in part because Beyeler made it so. Keller recalls a spectacular sculpture exhibition that Beyeler mounted in a public park in Basel – the greatest sculptors of the modern age: Rodin, Brancusi, Giacometti... Keller was a callow teenager, and this outdoor exhibition was an inspiration. Who knows how many other youngsters it inspired?

“Art is created by artists and not by dealers and collectors, but dealers and collectors can have a great effect,” says Keller. Beyeler was a catalyst. He brought buyers, sellers and makers of art together. And he brought them all together in a conurbation smaller than Southend. As Ropac tells me: “Small places, if they offer something extraordinary, they can succeed – if you have the right mix of people and the place and you offer something unique.”

It's easy to be seduced by the wealth and glamour of the art world. The huge prices and the immense prestige conjure up a kind of jet-set soap opera, reminiscent of the TV show Succession. Yet the most interesting discoveries don’t happen at swanky openings and private views. They happen in quirky hole-in-the-wall galleries, where creativity has room to thrive. That’s why, for me, the place that sums up the heady spirit of Art Basel isn’t the Kunstmuseum or Fondation Beyeler, but an unassuming exhibition space called Gallery Stampa, in the heart of Basel’s antique Altstadt.

Gilli and Diego Stampa founded this gallery in 1969, in their early twenties. In 1970, they exhibited at the inaugural Art Basel. They’ve been a perennial presence at Art Basel ever since, and they’ll be back there again this summer. After half a century, they’re still going strong, and so is their gallery – still in the same premises, a short walk from the old gallery where Ernst Beyeler started out.

Now in their seventies, still full of life and vigour, Gilli and Diego epitomise what’s so special about Basel’s art scene. Art Basel has grown and grown, becoming the most prestigious artfest on the planet, but there’s still room for folk like them at this art fair, and in this arty city. Unlike the liggers and the freeloaders, the influencers and Instagramers, they’re not interested in becoming rich or famous – they’re simply doing it for the love of art.

Art Basel (www.artbasel.com) runs from 15 to 18 June 2023. For more information about art in Basel and beyond, visit www.basel.com or www.myswitzerland.com

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

4Comments