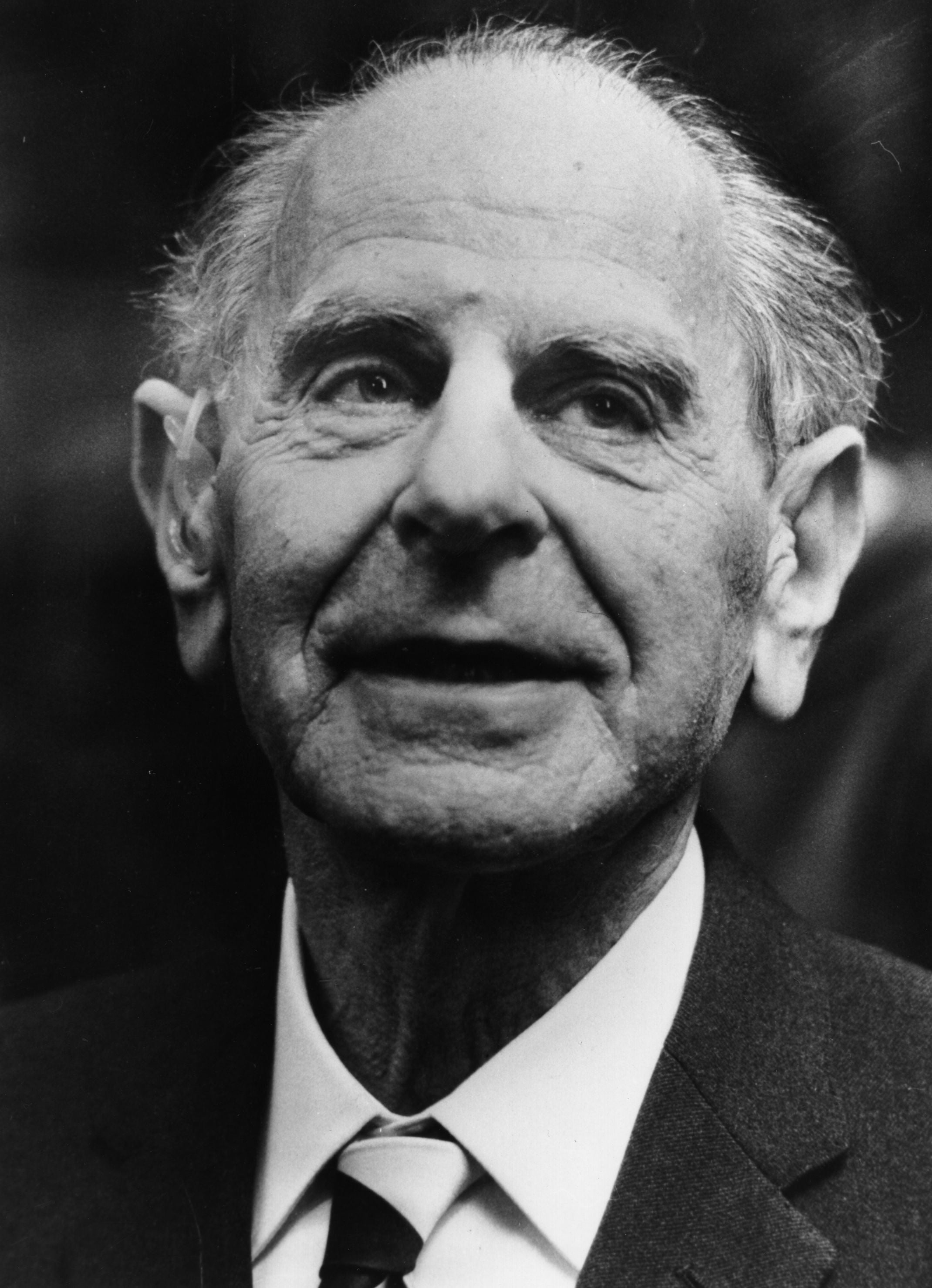

Sir Karl Popper: An important philosopher of science

The Viennese-born philosopher questioned the very bedrock upon which science is built, and what distinguishes science from other enterprises. His conclusions continue to divide critics today

Sir Karl Popper (1902–94) is certainly among the most influential philosophers of science in the 20th century, as well as an important critic of Marxism, but his reputation is still under consideration.

Reasonable people disagree about the real importance of Popper, about his actual standing in the history of philosophy. Enthusiasts hold well-attended Popper conferences, identifying him as “the philosopher of the century”. His loudest detractors point to large muddles in his allegedly best work and make sport of some of Popper’s incautious claims made late in life about the mind and the objectivity of theories. Cooler heads withdraw from the debate, maintaining that we are too close in time to Popper’s life and leave it to future philosophers to come to conclusions about his standing. We’ll join the latter group in the following paragraphs.

Popper was raised in Vienna following the First World War, and the times made a formidable impression on him. Although he was the son of a well-to-do lawyer, he witnessed poverty and political upheaval at first-hand. It moved him enough for him to undertake social work. He helped in a clinic for neglected children operated by the Freudian Alfred Adler, and it is clear that some of the events during this part of his life had an influence on his later philosophy. Certainly it had an effect on his conception of what distinguishes science from other activities like psychoanalysis.

He became a socialist and then a communist. Following the deaths of student and worker protesters at the hands of police, at least some of Popper’s communist acquaintances argued that the deaths were a help to the cause. Popper had different views about the value of human life and the ends of political action. The experience led to his rejection of communism and eventual critique of Marxism.

He attended the University of Vienna, earning a PhD with a thesis on the nature of method in psychology, as well as a qualification to teach mathematics and physics in secondary school. While working as a teacher in schools, his thesis caught the eye of certain members of the Vienna Circle – a group of philosophers, mathematicians, physicists and others who were instrumental in the logical positivist movement in the 1920s and 1930s. Popper became a contributor to the Circle’s discussions, and members of the group would eventually help Popper publish his first book, The Logic of Scientific Discovery. The book was read widely, and Popper was invited to lecture at universities both in the United States and Britain.

Popper’s parents, both from Jewish families, converted to Lutheranism in the hope of blending into Viennese society and had Popper baptized in the faith. Nevertheless, Popper was regarded as Jewish by the Nazis. His British colleagues had a great deal to do with helping Popper out of Vienna and into a philosophy post at University College, Christchurch, New Zealand. Popper remained there throughout the Second World War, teaching and producing his “war work”, The Poverty of Historicism and The Open Society and Its Enemies. Following the war, he took a post at the London School of Economics, where he continued to defend his views on the nature of science, politics and epistemology. We’ll now consider a part of his philosophy of science.

The problem of induction

Since Hume, philosophers have been lumbered with the problem of induction. Inductive inferences move from a number of particular observations, where several instances of a type of thing have been observed to possess a certain sort of property, to a general conclusion about all things of that type – whether we have seen them or not. Hence the predictive power associated with induction. This snail eats lettuce; so does this one; and this one; and this one too. So, all snails eat lettuce. I bet the next one I find eats lettuce. Inductive inferences seem supported by a principle of this form: if a very large number of things have been observed under all sorts of different conditions, and every one of them has had a certain kind of property, then all such things have that property. As Hume shows, this principle cannot be justified on either logical or experiential grounds.

The point is that the Freudian theory is not falsifiable; it has no negative empirical consequences. Thus, for Popper, it is no piece of science

The worrying fact for the philosophy of science is that science seems to proceed on inductive grounds. It’s not just our knowledge of snails, but a very large body of what we take to be paradigmatically justified knowledge, scientific knowledge, knowledge rooted in the rigours of scientific experimentation, which seems jeopardised by the problem of induction. If science depends on induction, and induction has no rational justification, is scientific enquiry therefore irrational? If so, and if you want to find a cure for cancer, why not consult an astrologer instead of a scientist? It’s probably cheaper.

We have here the two problems which Popper hopes to solve. In what does the rationality of science consist? What distinguishes science from other enterprises?

Popper attempts to avoid the problem of induction by arguing that scientific rationality consists in the falsification of theories, not the inductive verification of them. The view is based on a neat logical asymmetry. As we’ve just seen, you can observe as many snails as you like, but still your general theory that all snails eat lettuce will remain unproven. However, if you view just one snail which refuses to eat lettuce, you have produced a disproof of the general theoretical claim. It may be logically impossible to prove the truth of a theory by observation, but just one negative observation is enough to falsify a theory.

Falsifiable hypotheses

Popper views scientific endeavour as the tentative proposal of hypotheses or conjectures, which aim to describe some part of the world or solve some problem, followed by the vigorous attempt to falsify them with experimentation. Not just any general statement or theory counts as a scientific one. Given his views on scientific rationality, Popper argues that science works with falsifiable hypotheses, statements or sets of statements which might be undermined by observation, and this is part of what distinguishes science from other activities.

Some hypotheses are obviously not falsifiable on logical grounds – for example, there’s no experimental test which could show that “either snails eat lettuce or they don’t” is false. However, other instances of non-scientific hypotheses are a little more subtle. Suppose I tax you with my Freudian view that unconscious fears of a father figure actuate human behaviour. A little exasperated, you demand some empirical evidence. We go to a pub to observe human interactions, and spot a man hesitating to assert himself at the bar. I explain this easily as evidence that my theory is correct: the man is afraid of the barman; he sees him as a father figure and fears him; hence his hesitation. On the other hand, had the man banged his fist on the bar, demanding the barman’s attention, my theory could accommodate this just as easily: the man is attempting to overcome his fear of the barman, a father figure, by asserting himself.

The point is that the Freudian theory is not falsifiable; it has no negative empirical consequences. Thus, for Popper, it is no piece of science. On the contrary, good science consists in bold conjectures, which make a difference to how our observations ought to turn out. Thus Popper:

I can therefore gladly admit that falsificationists like myself much prefer an attempt to solve an interesting problem by a bold conjecture, even (and especially) if it soon turns out to be false, to any recital of a sequence of irrelevant truisms … In finding that our conjecture is false we shall have learnt much about the truth and shall have got nearer the truth.

Some argue that observation statements themselves are theory-laden. This is to say that all observations depend on some theory, even very low-level theory

You may rightly begin to smell a rat here. Is the claim really that scientists do or ought to try to undermine theories? It is hard to imagine scientists getting the champagne out on the discovery of an observation which conflicts with their pet theory, particularly if they have families to support and reputations to uphold. A number of objections to Popper deny that he has managed to describe or prescribe science in the right way – perhaps he has failed to take account of the social aspect of the scientific endeavour.

The aim of science

Further, science has practical aims; in the spirit of Bacon, we hope that science can improve human life, and serve as a basis for choosing and believing. But if we can never know whether or not a theory is true, as Popper has it, then how do we know which of our currently not-yet-falsified theories is the best guide for action? Popper’s answer is a little unnerving: theories which have survived ruthless testing should guide us. Unless we fall back into induction, though, we have no reason to think this is true.

It gets much worse, particularly when we carry on thinking about actual situations. First of all, scientific theories are not merely sentences about snails but sometimes vast structures supported by a number of auxiliary hypotheses. Testing situations, too, depend on additional theory, not least theory concerning the proper functioning of equipment and the precise nature of the initial conditions for experimentation. If a falsifying result occurs, one can locate the fault anywhere in a huge pile of theoretical claims and assumptions, keeping the kernel of the theory in place no matter what. If you do not get the result you were hoping for, maybe the machines need recalibrating.

Some argue that observation statements themselves are theory-laden. This is to say that all observations depend on some theory, even very low-level theory. Popper admits this, arguing that observation statements, like theoretical statements, are themselves tentative, accepted by convention, and susceptible to testing. He writes:

The empirical basis of objective science has thus nothing ‘absolute’ about it. Science does not rest upon solid bedrock. The bold structure of its theories rises, as it were, above a swamp. It is like a building erected on piles. The piles are driven down from above into the swamp, but not down to any natural or ‘given’ base.

Does it make sense to think of theories as things which can be falsified, given all of this? Some think it does, and Popper is not without an army of supporters who continue his work.

Major works

The Logic of Scientific Discovery (1935)

Sets out the doctrine of falsificationism, the view that science proceeds not by induction, but by the deductive demonstration of the falsity of scientific theory. The second part of the work deals with theories, testing, probability, quantum theory and the nature of corroboration.

The Open Society and Its Enemies (1945)

This is Popper’s major work in the philosophy of social science. It is a work in two volumes; the first volume is aimed at Plato, specifically his idea of “philosopher-kings” as the ideal rulers. The second volume deals with Karl Marx. It attempts to explain the rise of totalitarianism and says what ought to be done about it.

Conjectures and Refutations (1963)

Carries on the work of both earlier books, expanding on various falsificationist principles and applying them not just to the philosophy of science but to political philosophy as well.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments