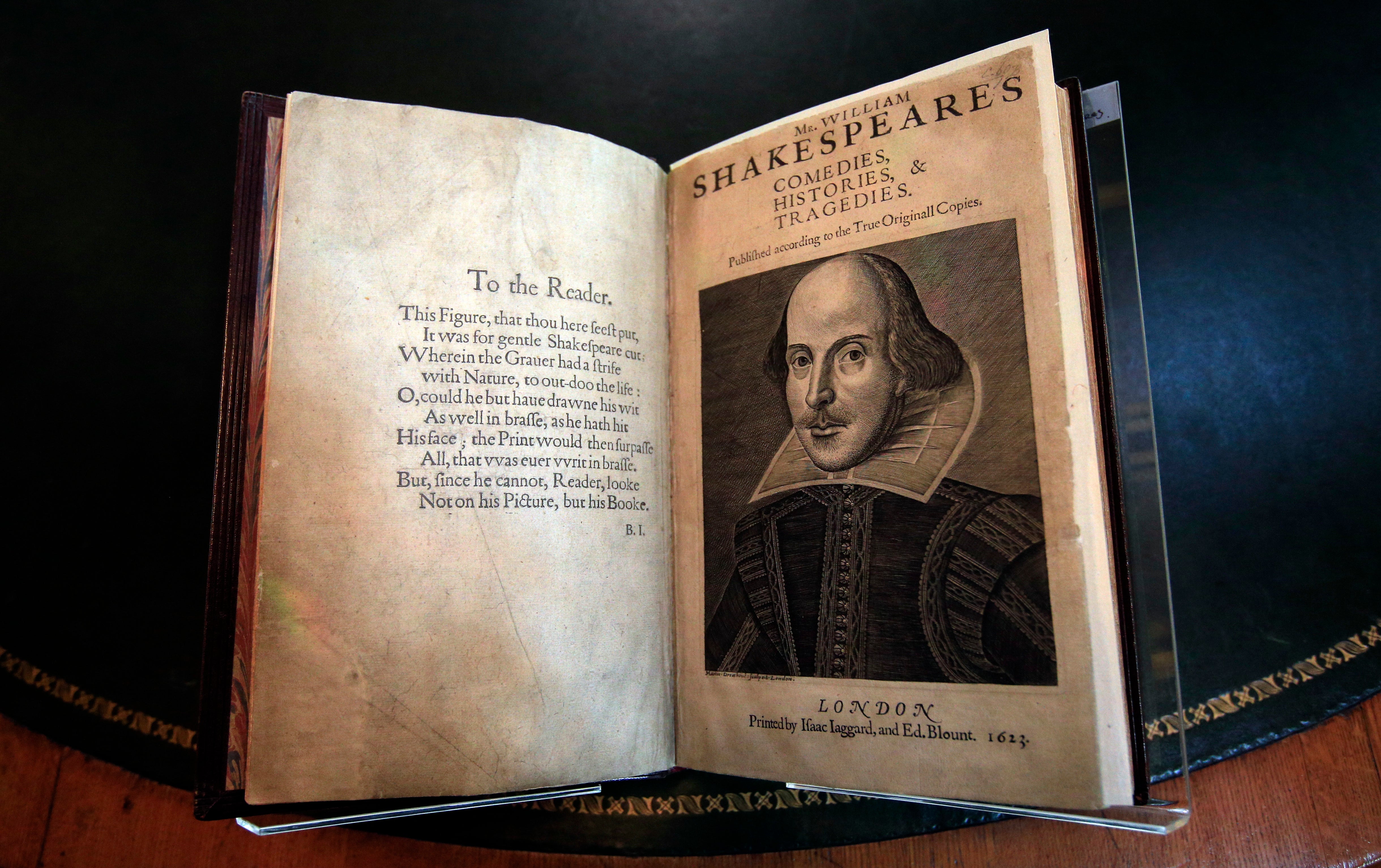

Book of a lifetime: Hamlet by William Shakespeare

From The Independent archive: Howard Jacobson on the intellectual pleasure derived from reading the Bard’s masterpiece as a novel

Funny to call Hamlet a book, but it was in book form that I first read it, and I have never thought of it other than as a “book”, or to be precise, a “novel”, since. As a novel it became mine, whereas whenever I see it acted not only is it someone else’s but it’s wrong. This is pretty much how Pip feels in Great Expectations (which, uncoincidentally, would have been my second choice of Book of a Lifetime) when he turns up to see his “gifted townsman” Mr Wopsle playing Hamlet, standing gloomily apart with folded arms and in curls he would have wished more “probable”.

There’s the catch with Hamlet on stage – even Olivier failed to rescue him from the preposterous, whereas in a novel he is the noble-minded sweet prince Horatio believed him to be, his alternating rages and reflection well-suited to the pace of novel reading, his conversation too realistic for stage conventions, the music of his wit something you need to relish slowly and go back over. It is the most modern of Shakespeare’s plays by some margin. In it, I fancy, you hear how Shakespeare might have talked.

In the somewhat patronising affection he expresses for Horatio, in the bruising banter he exchanges with Guildenstern and Rosencrantz, in the love he shows the players, we get a whiff of London conversation in the age of Elizabeth, the chilly ramparts of Elsinore Castle notwithstanding. “Thanks, Rosencrantz and gentle Guildenstern,” Claudius says, after they have agreed to keep an eye on their friend. It isn’t exactly betrayal. Hamlet has been behaving oddly and it behoves friends to be concerned. “Thanks, Guildenstern and gentle Rosencrantz,” says Gertrude, the flirt. But it’s kindly flirting. Why should Rosencrantz miss out on being described as gentle?

The unfolding of what Gertrude is like, how she both answers to Hamlet’s brute understanding of her as a woman without loyalty, and yet eludes him in her indiscriminating affectionateness, is masterfully done. I want to be able to relish that and not see some voluptuous actress in breathy middle age showing me her cleavage, which is the usual way of playing Gertrude. It’s Gertrude who delivers the observation, “Methinks the lady doth protest too much.” You can tell those who know Hamlet as a play from those who know it as a novel by the differing ways they employ that line.

Theatre-goers connive in Gertrude’s cynicism and use it as a condemnation of people who are too vehement on their own behalf; novel readers know it contains the essence of Gertrude’s soul – her incapacity to understand that anyone can be steadfast in their emotions. Play or novel, Hamlet is wonderful about judgement, how harsh the intelligent are, how wrong and lonely in their harshness, but how without them the world goes undescribed. From Hamlet I got the idea early that though living in one’s mind is terrible, there’s nowhere better.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks