Book of a lifetime: Le Parti Pris Des Choses by Francis Ponge

From The Independent archive: Tom McCarthy on how the unorthodox style of the French ‘proet’ continues to inspire him

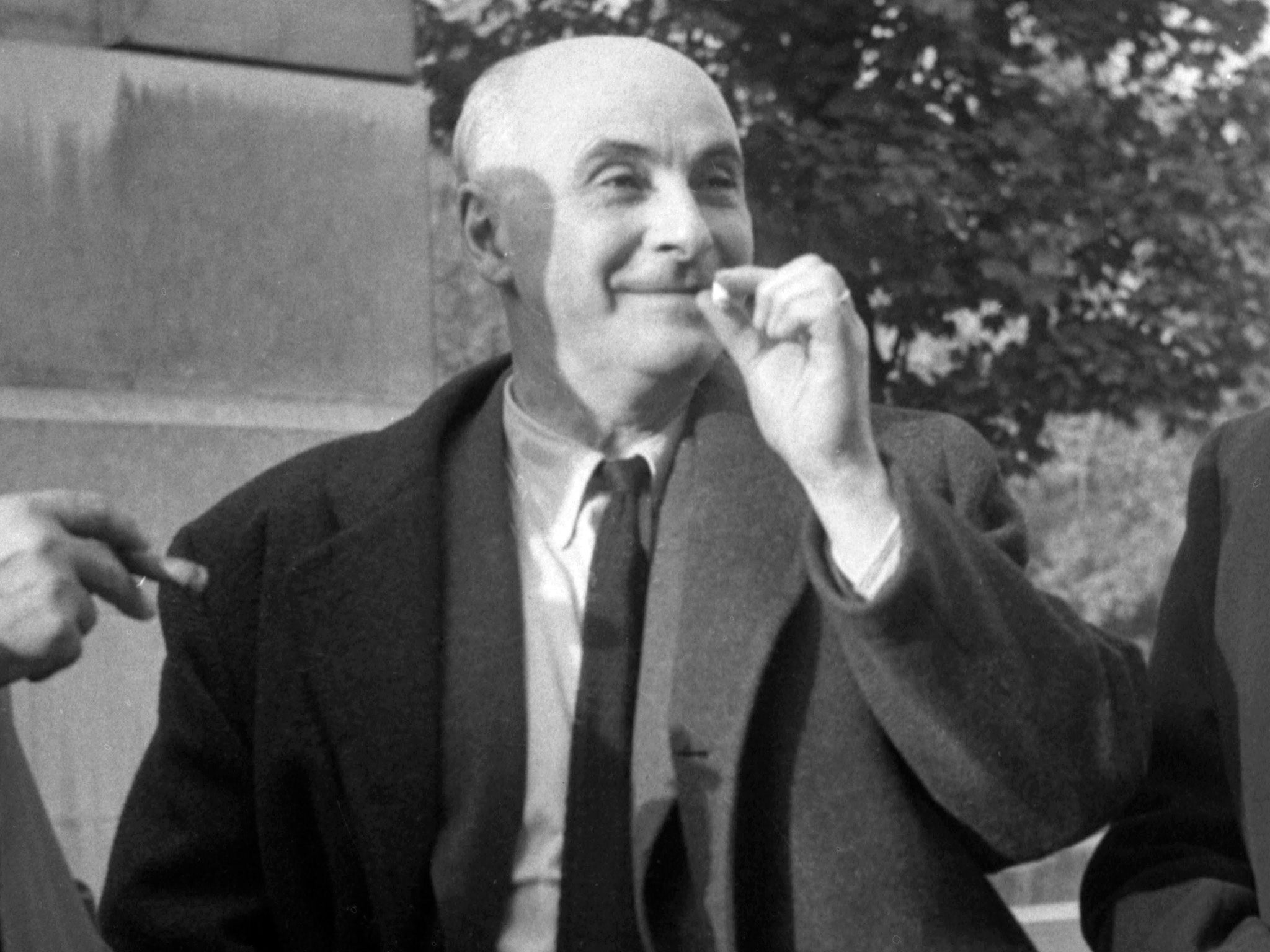

In 1991, just out of college, I bought a copy of Francis Ponge’s “Le Parti Pris des Choses”. Ponge, one of the signatories of the “Surrealist Manifesto”, is usually described as a “poet” – yet the label doesn’t quite fit. For a start, he wrote in prose. Strange prose, it must be said: short paragraphs so rich with metaphor and all the tricks of rhetoric (apostrophe, the interrogative, declamatory exhortations such as “Let us consider...”) that, as with the best poems, we’re disoriented from the start by being immersed in language and nothing but language, with all its quicksand-like shiftiness, its sleights of hand, its endless self-adjustments and self-contradictions.

Ponge even made a term up for his hybrid form, naming one of his collections “Proêmes”. Tip for the young, aspiring writer: if you want to learn how to write, sit down and translate a foreign master into English. That’s what, aged 22, I tried to do with “Le Parti Pris des Choses”. It’s not really possible to do it “correctly”, but that’s the point. Even the title’s untranslatable: it could mean “Taking the Side of Things”, “Taking Things On”, or “Taking a Part (Out) of Things (but Leaving the Rest Behind)”.

The ambiguity runs through the whole collection, shaping it at every level. Ostensibly a set of descriptions of banal, everyday objects such as an orange, a cigarette and an oyster, “Le Parti...” is a monumentally ambitious disquisition into the relationship between the world and consciousness, reality and our attempts to represent it. Thus the orange, when it undergoes “the ordeal of expression” – that is, of being both squeezed and represented – leaves in our mouths (whose larynxes “are obliged to open as widely for the pronunciation of the word ‘orange’ as for the ingestion of its liquid”) the “bitter consciousness of a premature expulsion of pips”.

The oyster shields both world and heavens beneath a “firmament” of shell on which we break our fingernails; sometimes, though rarely, a “formula” (a brilliantly loaded term) “pearls in its nacreous throat”. What all this amounts to is the greatest anti-idealist manifesto possible. Whereas for Hegel and his followers, the task of art is to abstract the world into pure concept, Ponge returns both world and concept to their rich material bases. As the philosopher Simon Critchley likes to put it, he “lets matter matter”.

Other poets – Wallace Stevens, for example – and philosophers (Bataille, Deleuze) have argued for this approach, but Ponge enacts it at a molecular level. Even his name, its very letters, become mired in materiality: when a sponge (in French, eponge) enters the fray, the poet (sorry, proet) is all too aware that the object’s name contains his own. Identity itself is sponged away, but also gathered up within amorphous tissue, to be re-expressed forever. Here, in the lowliest of objects, is the miraculous – and messy – potentiality of literature. And Ponge, for me, now as much as back in 1991, is the embodiment of what a writer should aspire to be.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments