Grumpy on screen: Why we love curmudgeons

As Tom Hanks is back on screen this week playing a bad-tempered widower in ‘A Man Called Otto’, Geoffrey Macnab looks back at the long line of cantankerous heroes in film and wonders if what makes them appealing is that they don’t care what people think about them

The scowl contorts the much-loved actor’s face. There are deep furrows in his brow and a look of misanthropic malice in his eyes. This is Tom Hanks as a grumpy widower in A Man Called Otto – out in cinemas today. In this remake of the 2015 Swedish comedy-drama A Man Called Ove, the sainted star of Forrest Gump is, as journalists have quipped, turned into “Forrest Grump”. He plays a cantankerous, angry and deeply unpleasant man who has given up on life since the loss of his wife. Whether it’s the neighbour’s dog peeing on the pavement or the van driver who parks in the wrong place, he finds almost every minor incident in his life exasperating beyond belief. Otto is like an even more enraged version of Richard Wilson’s Victor Meldrew in the 1990s TV sitcom, One Foot in the Grave.

You might imagine audiences would be repelled by someone as cranky as Otto. In fact, the reverse is the case. Look through film history and you will find audiences continually warming to curmudgeons on screen. Sometimes, this is because the Scrooge-like protagonists belatedly discover the milk of human kindness – and the films end in redemptive fashion, with lots of smiley faces. Hanks’s Otto is a case in point. Instead of killing himself – his original plan, which he bungles – he befriends his pregnant new neighbour (Mariana Trevino) and her young family. In their presence, his emotions thaw, and his optimism and conviviality return.

“Fall in love with the grumpiest man in the world,” the poster for A Man Called Otto encourages audiences. It’s an invitation some viewers are struggling to accept. The film has been receiving distinctly mixed reviews, primarily because critics find it just too schmaltzy.

Many of cinema’s most memorable curmudgeons are at their best when they’re at their nastiest – and when, unlike Otto, they stay that way. What makes them appealing on screen is that they don’t care what people think.

Comedian WC Fields was a virtuoso in screen grumpiness and you rarely saw him trying to ingratiate himself by showing a more tender side. In the 1933 film Tillie and Gus, in which Fields plays Augustus Winterbottom, a chancer in pursuit of an inheritance, there is a famous scene in which the comedian is asked: “Do you like children?”

“I do if they’re properly cooked,” he replies without missing a beat.

Fields often got his biggest laughs by picking fights with kids. In his movies, cosy, middle-class domesticity is portrayed as hellish in the extreme. A meal around a table with family and neighbours is a trial of endurance. In his 1934 vehicle, The Old Fashioned Way, the bulbous-nosed comedian is shown having a running battle with a tot (Baby LeRoy) on a high chair. Every time his mother’s head is turned, little Albert will perform some new act of domestic terrorism against Fields’s character, the actor-manager known as The Great McGonigle. The scene culminates with the baby filching Fields’s beloved watch fob and dropping it in the molasses. While the other adults are still at the table, Fields has to show forbearance. He shrugs off the indignities heaped on him. However, once the grown-ups are lured out of the room and he is left alone with Albert, he can’t resist giving the little boy a very big kick.

In his book WC Fields: Life on Film, the comedian’s grandson Ronald J Fields reveals that when the sequence was first shot, Fields knocked Baby LeRoy high in the air with the sheer force of his shoeing. Paramount executives were aghast, demanding the scene be cut out lest it received “a roar of disapproval from the audience”. Fields stood his ground and insisted the kick stay in the movie. His only concession was to shoot it again and to apply his foot on the rump of his nappy-wearing co-star very marginally less forcefully the second time around.

Quite rightly, violence against children is considered one of the greatest taboos in cinema. You’d struggle to find a movie star today who would endorse the comedian’s stated opinion that “there’s not a man in the world who has not had a secret desire to boot a kid”. Fields, though, is invariably the butt of the joke. The drunken old ne’er-do-well continually finds himself being outwitted. Like the hapless gangsters humiliated by Macaulay Culkin in the Home Alone films, he is the one having his nostrils twisted and being ritually humiliated by antagonists a fraction of his age.

For all his tantrums, Fields was among the most benign of screen curmudgeons. There was something anarchic and surrealistic about his behaviour. He rarely seemed truly malevolent. Other cinema sourpusses have been far, far meaner.

The great Hollywood character actor Walter Matthau (1920-2000) had an uncanny knack of making everyone he played seem cranky and hostile. Whether in the frantic crime thriller Charley Varrick (1973), Billy Wilder’s 1974 version of the newspaper drama The Front Page, or when giving his Oscar-winning performance as a cynical, opportunistic lawyer in Wilder’s 1966 comedy The Fortune Cookie, he was always the same sardonic, grumpy presence. Tall, stooping and with a moose-like demeanour, he was naturally dour and lugubrious. He didn’t so much say his lines as growl them out.

Matthau wasn’t as handsome as all the blandly good-looking stars of the period but had a force of personality they lacked. He started his movie career playing villains in films like The Kentuckian (1955) and King Creole (1958) but eventually became a leading man. He may have been permanently grouchy but he had charm. He also combined brilliantly with his regular co-star, the far smoother and more ingratiating Jack Lemmon, with whom he appeared in films from The Fortune Cookie and The Odd Couple (1968) to Grumpy Old Men (1993).

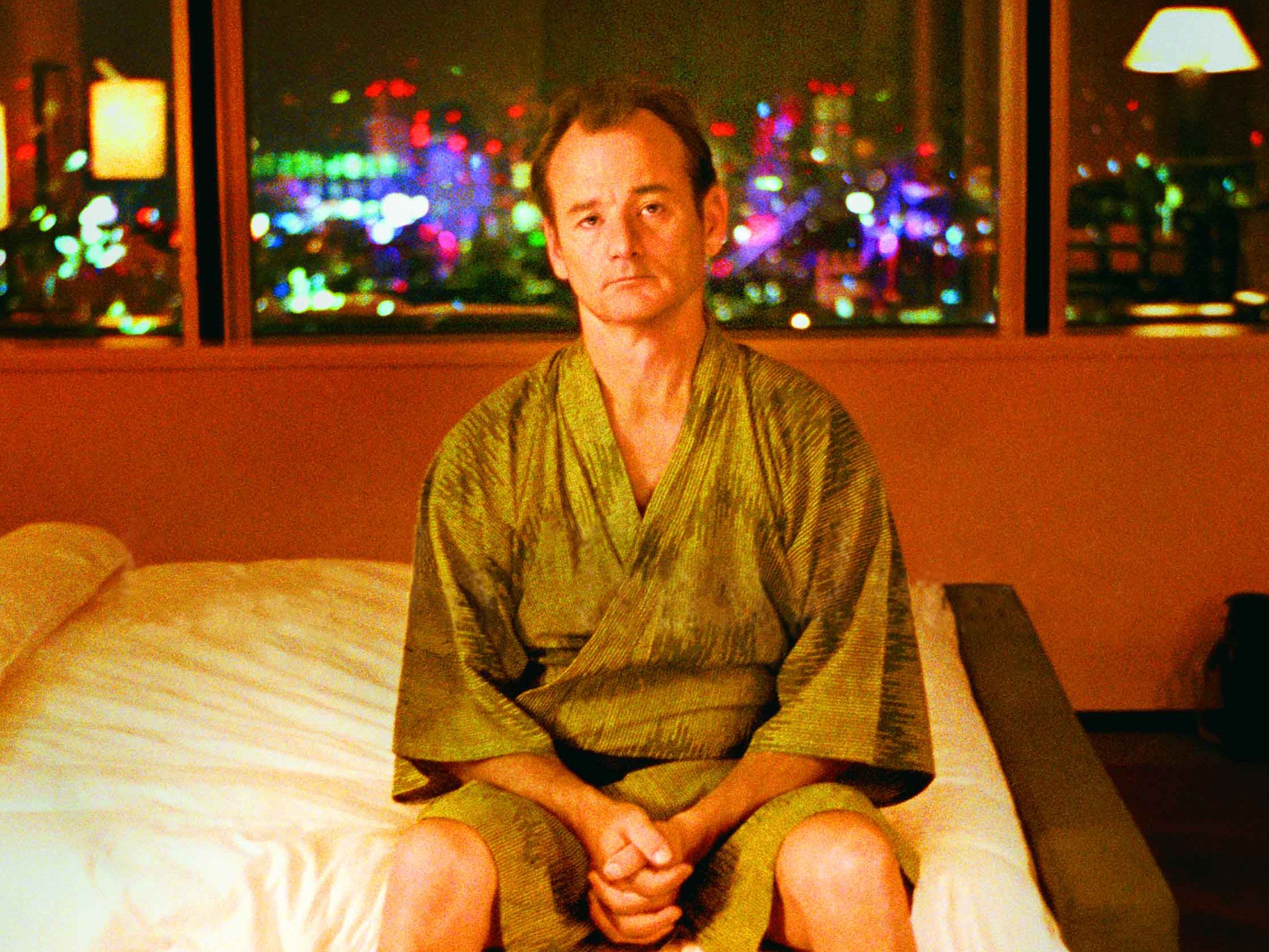

Bill Murray, who is as close as contemporary cinema comes to its own Walter Matthau-like grinch, stated in a 2004 interview: “I know how to be sour. I know that taste.” In films from Scrooged (1988) to Groundhog Day (1993) and Lost in Translation (2003), he played characters as fed up with life as Hanks’s Otto. Murray, now 72, used to excel at portraying middle-aged angst and ennui. He was dry, sarcastic and had brilliant comic timing.

Recent allegations of feuds with co-stars and “inappropriate behaviour” on his sets suggest Murray sometimes behaved as objectionably off camera as on. The actor, though, never pretended he was nice. The whole point about the best screen curmudgeons is that they don’t try to get us to like them. Generally, the more unsympathetic their behaviour, the more vivid they become. That is certainly the case with Maggie Smith in Nicholas Hytner’s film The Lady in the Van (2015). She is playing Miss Mary Shepherd, a mentally disturbed old bat who lives in poverty in a clapped-out old Bedford van. She is a “sick woman looking for a last resting place” who makes outrageous demands on writer Alan Bennett (Alex Jennings) after he allows her to park her vehicle in his Camden driveway. Miss Shepherd may not be pleasant or rational but she is very strong-willed – and that is what makes her such a lively subject for a film.

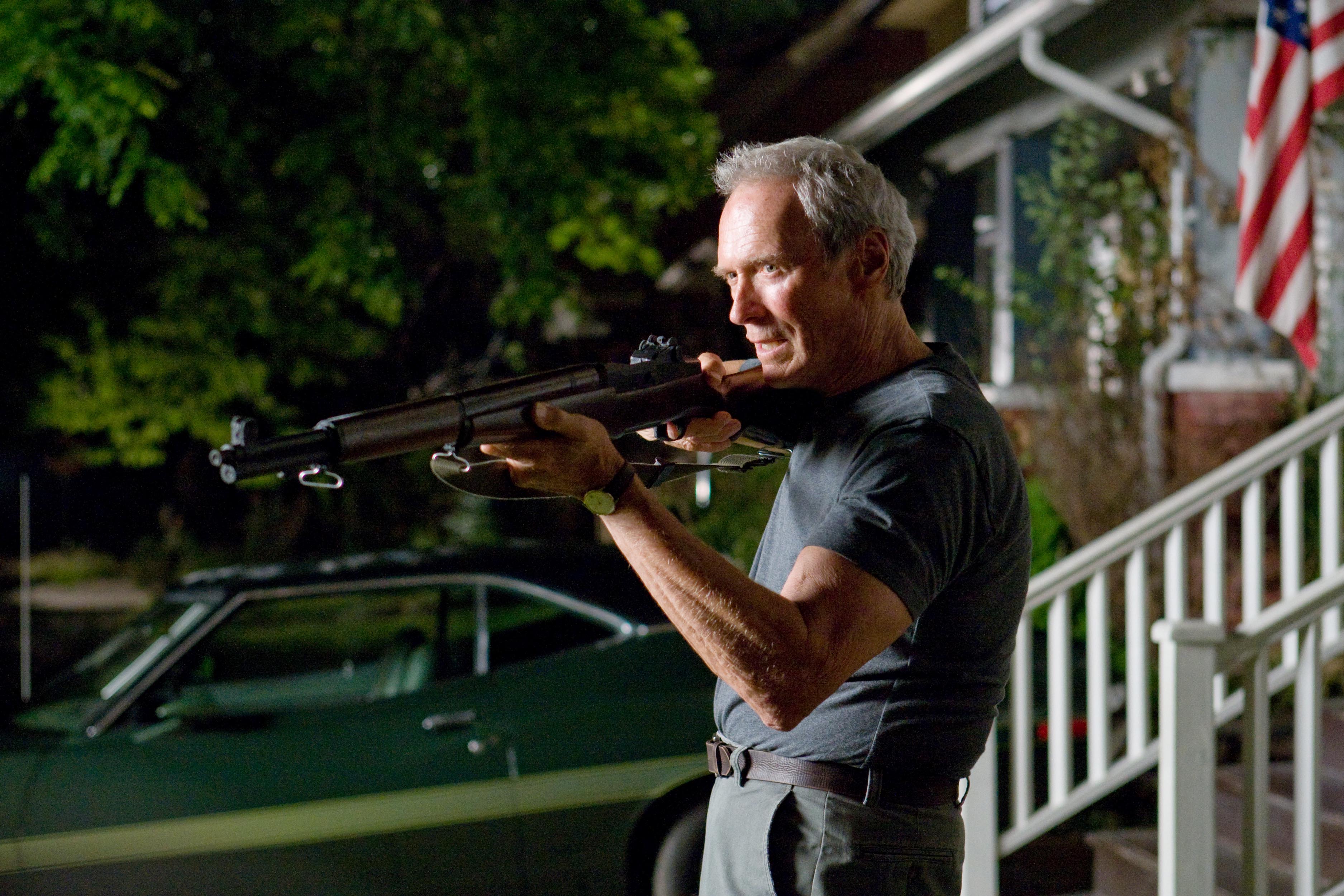

A legendary actor like Clint Eastwood could get away with playing truculent patriarchs in some of his later films because audiences had such fond memories of him starring in all those westerns and cop movies in his prime. Angry vigilante OAPs like Eastwood’s widowed Korean War veteran in Gran Torino (2008) aren’t that far removed from the vengeful outlaw he played in Unforgiven (1992) or from his leading role in Dirty Harry (1971). He was still challenging street punks to make his day. The difference now was he was older, meaner and far more arthritic.

There is an obvious sexism when it comes to curmudgeons on screen. Whereas films abound in which grumpy old men like Hanks’s Otto are shown looking for redemption, grumpy old women – Smith’s street tramp notwithstanding – tend to be treated with far less sympathy. It is noticeable that Hollywood stars like Bette Davis and Joan Crawford were regularly cast as harridans in the latter part of their careers. The characters they played in What Ever Happened to Baby Jane? (1962) or that Davis played in Hush…Hush…Sweet Charlotte (1964) and The Nanny (1965) have a psychotic quality. Whether they’re plotting someone else’s downfall or are the victims of evil machinations themselves, they’re equally grotesque.

The best screen curmudgeons don’t need sugar coating. Films like A Man called Otto and its Swedish counterpart A Man called Ove are undermined by their creeping sentimentality. Starker stories like The Lady in the Van or Alexander Payne’s Nebraska (2013), in which Bruce Dern played the ferociously bad-tempered senior citizen, ultimately have more of a kick because they are so caustic and unforgiving. Humour helps too. From Fields to Murray, the irascible old devils we tend to cherish the most are those who know just when to put the boot in. Why do we root for them even when they are misbehaving? After the relentless drip of movies featuring gorgeous, do-gooder heroes and heroines, there is something inherently refreshing about crusty, woebegone characters who are as frustrated by the challenges of everyday life as we are – and who respond in such petulant and small-minded fashion.

When WC Fields is playing golf in his film The Dentist (1932), he gets more and more furious as his ball keeps on plopping in the lake. First, he hurls his club into the water. Next, he throws his bag after it. Finally, he picks up his caddy and chucks him in the water for good measure before storming off the course in a huff. Now that is behaviour you just have to applaud.

‘A Man Called Otto’ is in cinemas from 6 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments