Books of the month: From Jonathan Franzen’s Crossroads to Sarah Hall’s Burntcoat

Martin Chilton reviews five of October’s biggest releases for our monthly column

October is bursting with celebrity memoirs, as comedians, actors and musicians, including Nirvana and Foo Fighters star Dave Grohl, rush to wear their hearts on their literary sleeves. There are two crackers coming at the end of the month. Brian Cox’s Putting the Rabbit in the Hat: My Autobiography (Quercus) grips from the beginning – a witty prologue about the preposterousness of Steven Seagal – and is the sort of riveting, candid read you might expect from the illustrious Succession actor. Fellow Scottish thespian Alan Cumming will also have you laughing and squirming with Baggage: Tales from a Fully Packed Life (Canongate), which includes a memorable account of just how grim it was to spend a weekend as the guest of a drunken, cantankerous Gore Vidal.

I listened to David Sedaris reading Theft by Finding, the first volume of his diaries, on audiobook and could still hear his voice in my head while feasting on A Carnival of Snackery – Diaries: Volume Two, 2003-2020 (Little, Brown), which is full of the same sardonic barbed wit. The book displays his admirable taste for the grotesque, and although world affairs feature in his daily accounts – the “con man” Donald Trump, Brexit, coronavirus – his funniest observations deal with the quirks of the great unwashed. Oh, and there are jokes galore, again, as with his entry for 25 September 2007: “Paris. To honour the death of Marcel Marceau I observed a minute of silence.”

In Major Labels: A History of Popular Music in Seven Genres (Canongate), Kelefa Sanneh takes on the ambitious task of summarising the story of rock, R&B, country, punk, hip-hop, dance and pop in around 450 pages. The book is immensely readable, and full of rich detail. The chapter on country music, for example, is engrossing, and anyone who describes Iris DeMent as “transfixing” gets my nod of approval as a music critic. Another impressive music book out this month is From Manchester With Love: The Life and Opinions of Tony Wilson (Faber), Paul Morley’s account of the action-packed life of the man who made such a mark with Factory Records and Manchester’s celebrated club The Hacienda.

Another music book that comes highly recommended is Michael Church’s Musics Lost and Found: Song Collectors and the Life and Death of Folk Tradition (Boydell & Brewer Ltd), which is an engrossing study of the pioneering role played in musical history by song collections. Church, who writes on classical music and opera for The Independent, also casts a shrewd eye over the so-called “world music” boom.

John Banville has followed up the superb Snow with the hugely enjoyable April in Spain (Faber), which again features Detective Inspector St John Strafford. This time, he’s a minor character in a pacy crime thriller set in London, Dublin and Donostia (San Sebastian). It’s a novel that features a slew of fine characters; my favourite is the eccentric hitman Terry Tice, a sociopathic killer who offers literary criticism of Graham Greene’s Brighton Rock, claiming the author didn’t spot Pinkie’s “real problem” because he was “too busy brooding about death and the hereafter”.

The sharply humorous 66-page title story was the best in Lucie McKnight Hardy’s collection Dead Relatives and Other Stories (Dead Ink). I liked Christine Smallwood’s droll, unsettling debut novel The Life of the Mind (Europa Editions), about an English professor coping with a failed pregnancy. Two recommended books in translation this month are Trust by Domenico Starnone (Europa editions, translated byJhumpa Lahiri), a powerful exploration of love, and Lemon, by KwonYeo-sun (Apollo, translated by Janet Hong), a chilling crime story about the murder of a Korean teenager, in a case that was dubbed the “high school beauty murder”.

Fans of Jane Austen will enjoy Freya Johnston’s Jane Austen, Early and Late (Princeton University Press), which examines some of the teenage writings from the author of Pride and Prejudice, many of which were, surprisingly, full of “gallows humour”.

Robin Williams described Gus Van Sant as a director “so subtle he’s almost subliminal” and there is a wonderful photograph of the comedian joshing with Matt Damon in Katya Tylevich’s impressive Gus Van Sant: The Art of Making Movies (Laurence King Publishing). The book also recounts the story of how Van Sant deferred to the actor about the crucial final line in Good Will Hunting, a remark the late Williams improvised on the spot.

The new novel from Jonathan Franzen, along with fiction from Sarah Hall and Roddy Doyle, and non-fiction about science and the history of libraries, are reviewed in full below.

Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen ★★★★★

Crossroads, the captivating first novel in a new trilogy from Jonathan Franzen, opens on 23 December 1971, and tells the story of the Hildebrandt family, who live in the “Crappier Parsonage” in New Prospect, a suburb of Chicago. Franzen masterfully evokes the complicated emotional fallout from household grudges, rivalries and insecurities.

Franzen, who won a National Book Award and Pulitzer Prize for his 2001 novel The Corrections, writes with precision and empathy about the way family members know how to manipulate each other, about their ability to hurt each other in the most piercing ways – and how internal household conflicts can rupture and spill out in devastatingly spiteful home truths.

The Hildebrandts have intimate knowledge of each other’s failings – and many of the complaints focus on the Reverend Russ Hildebrandt, the head of the family. Russ, a middle-aged associate pastor, is a frustrated, embittered man. His marriage is unravelling, his career has ossified and he has suffered professional humiliation at the hands of a hip young minister he despises – a man who wheedled away control of the church youth group Crossroads.

Crossroads is a metaphor, of course. Every Hildebrandt is facing a crunch moment. Russ’s wife Marion, who hates the way she has developed “a sausage of a body”, is full of secrets, some of which she spills to a psychiatrist she dubs “the dumpling”. Clem, their oldest son, is consumed by his own sexual confusion and his guilt about avoiding conscription to the Vietnam war. Clem feels “shame” about being the son of a man he regards as a “moral fraud”. His sister Becky, with whom he has a complicated relationship, one full of incestuous undertones, is the “the social royalty” of her high school but is lost in a moral maze after turning 18.

Becky also hates being a minister’s daughter. Her younger teenage brother Perry, her bete noire, is the wild, drug-taking black sheep of the family. Perry openly feuds with his father. Russ, in turn, recoils from the “mildew stink” that clings to his bright, wayward son. Even Judson, the baby of the family at nine, is starting to change, losing his innocence about the world. As the snow falls and the Christmas lights sparkle, you fear that disaster looms from the very start.

Crossroads, which maintains suspense throughout 580 pages, is superbly told through deft interwoven perspectives. As the novel progresses, the revealing histories of the older characters come to light, offering a deeper understanding of what has forged such troubled parents.

Franzen’s nuanced story of dishonesty, infidelity, and the aching need for love and understanding, has thought-provoking things to say about the way failed relationships can inflict lasting damage on mental health. The novel is also an engrossing meditation on faith and belief, set during a fraught time in American history. Darkness lurks in the background, whether it’s the toxic presence of armed conflict, the insidious nature of racial injustice (interaction with the Navajos is a key element of the book), the pain of sexual inequality or the predatory behaviour of men towards women.

The compelling dialogue, the authenticity of place, time and character, the assured insights and the exquisite minutiae of description, all confirm that the reader is in the hands of a true modern master. Crossroads is a simply stunning novel.

Crossroads by Jonathan Franzen is published by 4th Estate on 5 October, £20

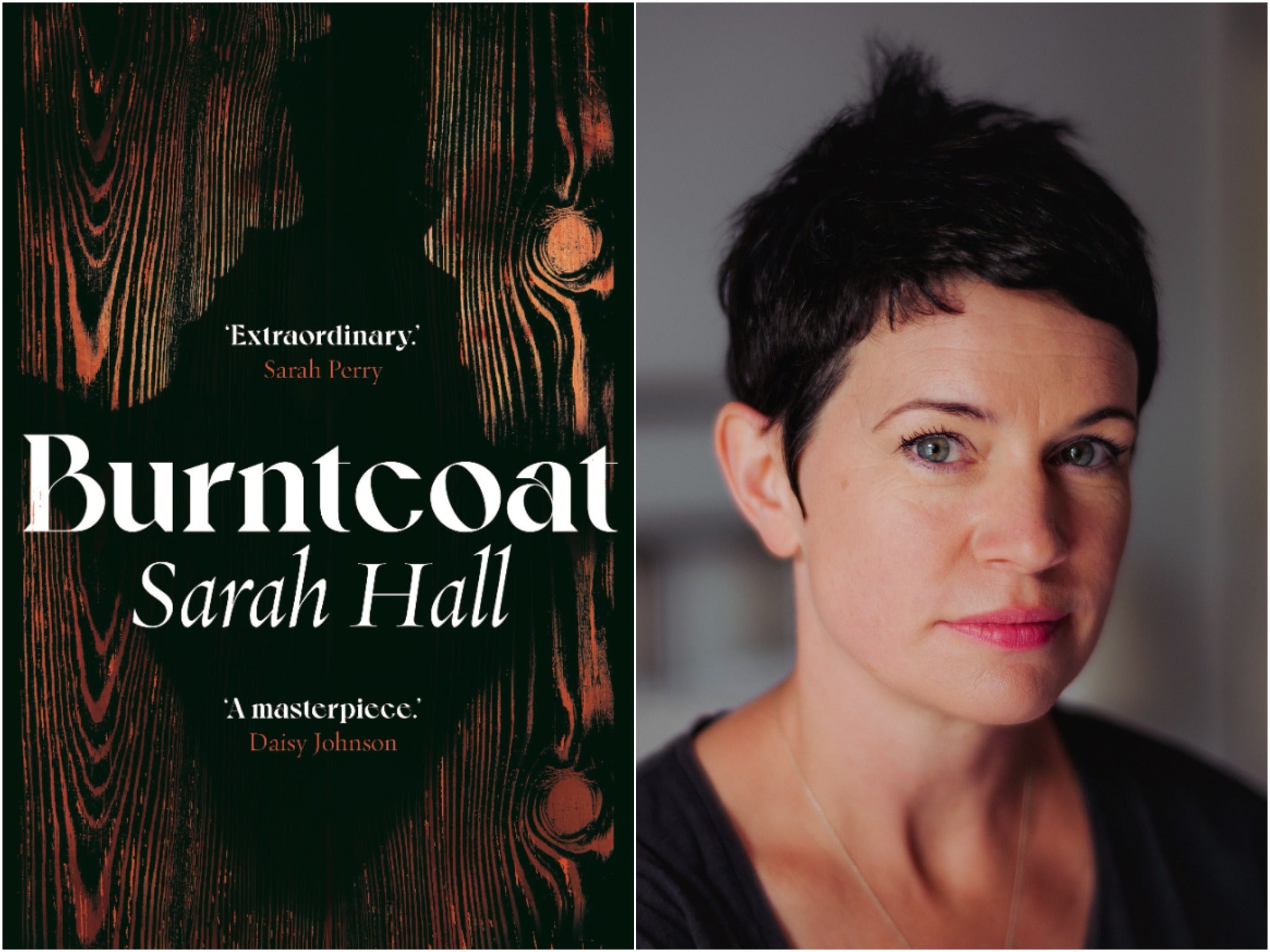

Burntcoat by Sarah Hall ★★★★☆

The absurd theatre called life has always been something hard for the venerated sculptor Edith Harkness to get to grips with. Her childhood was tough. Her cold, weak father walked out after his wife Naomi suffered a horrendous brain haemorrhage, leaving Sarah Hall’s protagonist in Burntcoat to be raised “by a borrowed woman and her shadow”.

Now old, and living in the immense studio at Burntcoat, Edith tries to make sense of the transitory nature of existence, her fractured past, the challenges of work as an artistic creator and the painful memories of long-lost friends and lovers. This self-reflection comes at the same time as she is struggling to come to terms with the pandemic and existing in an era of quarantine. “Strange times… the phrase we would all use, again and again, until it was devoid of meaning.” Edith is also trying to make sense of her feelings about rotten past lovers and the enriching, perhaps fated relationship, with her lockdown lover Halit. Hall, who has twice previously been nominated for the Booker Prize, skilfully probes the way that confined existence exacerbates existing wounds to the psyche. Burntcoat is a beguiling tale about our unending struggle to work out how to exist and how to learn to live with loss.

Edith is a tremendous protagonist and Hall’s tender, scorching novel will make your heart weep for a woman whose “soul had capsized”.

Burntcoat by Sarah Hall is published by Faber on 7 October, £12.99

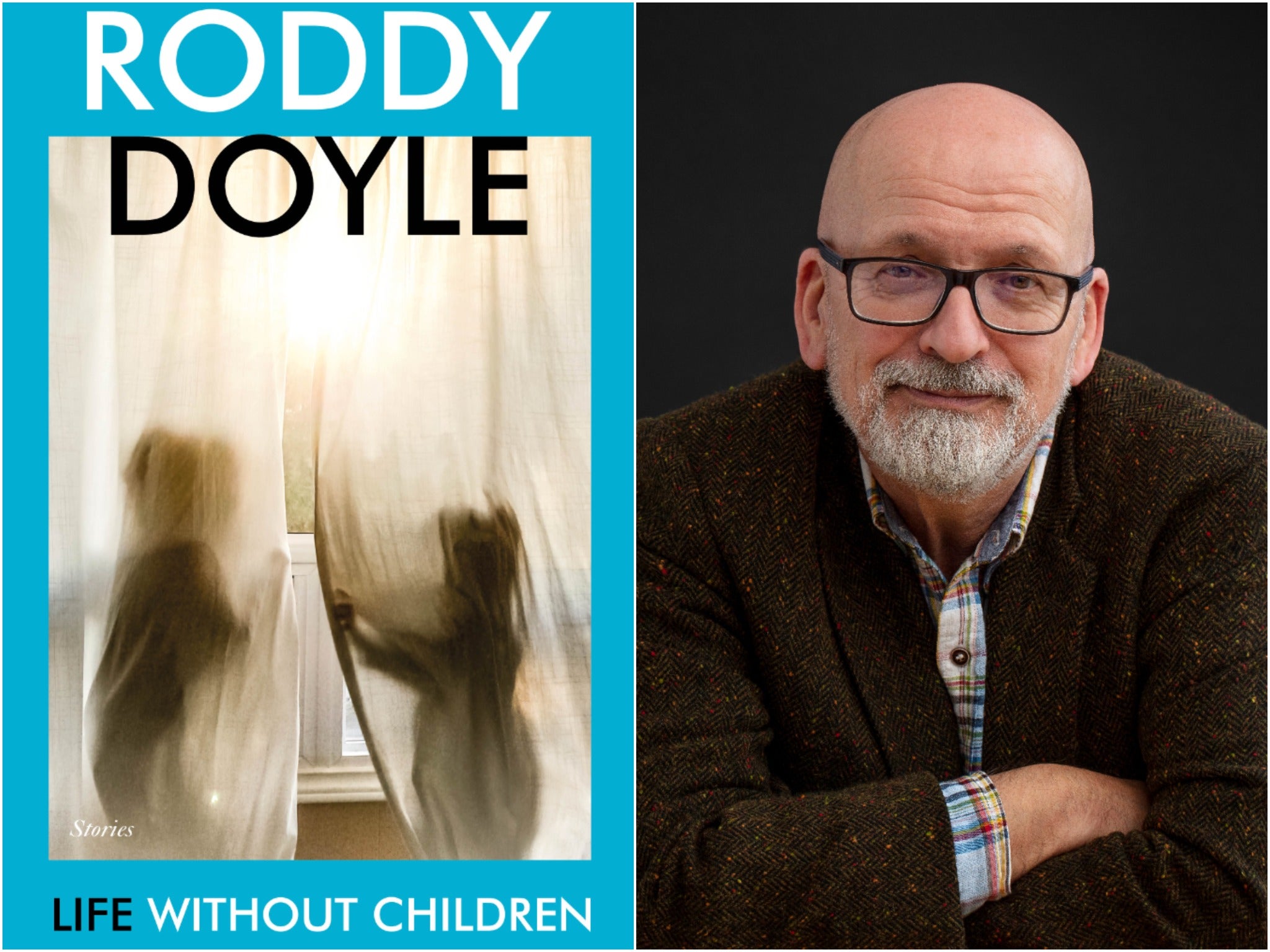

Life Without Children by Roddy Doyle ★★★★☆

If you are looking for an affable guide to what it’s like being stuck in a Covid-hit world, then Roddy Doyle would come high up the list. In the 10 short stories that make up his wonderful collection Life Without Children, the Dubliner offers a wry, sometimes sorrowful, window into lockdown life, a time when “a bag of chips has never been so exciting”.

In Funeral, the desultory story of a middle-aged man barred from his mother’s burial, you can’t help but empathise with a man who sticks on the radio and tries to take in the reality of coronavirus, “the stats, the new language”. Doyle is a master of capturing the everyday and he turns his watchful eye on to the bits and pieces of pandemic life: the disturbing sight of soiled and abandoned face masks, “damp and lethal on the concrete, like leaves”, or the street walkers swerving each other as if they were all on skis.

In Doyle’s ludic Ireland – a place where a dog is named Dog – you see the damage the virus has done. In the story The Five Lamps, the man roaming around Dublin looking for his long-lost son sees a city where “half the premises are already shut down, just waiting for the pandemic to put them out of their misery”.

Nurse is a simple, haunting tale of life on the NHS front line. The superb Worms is about the restorative joys of music and love in lockdown, even if the sounds are coming from someone as supposedly uncool and simply human as the lovely John Denver.

The 63-year-old Doyle also adroitly analyses and sends up middle-aged decline. There is a passage in the title story that is laugh-out-loud stuff: “Geoff worked at home – Alan hadn’t a clue what he did – and he’d got himself a desk that allowed him to stand as he worked. That must be some f***in’ desk, said another of the husbands, if you have to ask its permission if you want to stand up. I have a back thing, Geoff told them, and some of the other men had nodded. They had back things too.” Life Without Children is full of unpredictable, funny and mournful gems.

Life Without Children by Roddy Doyle is published by Vintage on 7 October

The Importance of Being Interested: Adventures in Scientific Curiosity by Robin Ince ★★★★☆

We are, according to Robin Ince, “perpetually submerged in the media of constant anecdote”. The Importance of Being Interested will gladden the heart and stimulate the mind of anyone fed up of being mentally polluted by the modern social media slurry of lazy supposition, paranoia and misinformation.

Ince, the comedian who is co-creator and presenter of the BBC Radio 4 show The Infinite Monkey Cage, wrote the book during lockdown, conducting more than 100 interviews with astronauts, comedians, musicians, teachers, neuroscientists and quantum physicists. His passion for science is infectious, even to this reader, whose scientific ability reached no higher than a C-grade physics O-level scraped some 40 years ago.

The Importance of Being Interested, which has a foreword by Professor Brian Cox (it’s a busy month for Brian Coxes, although this one is the big-brained physics expert, not one who plays Logan Roy) is challenging. Getting your head round the notion that the universe is expanding faster than the speed of light – “the star-formation rate is a remarkable 4,800 stars per second” – is discombobulating. Our galaxy alone is 100,000 light years across. It’s hard to compute. Ince uses Star Trek references to make these impossible figures vaguely understandable. “The USS Enterprise’s five-year mission starts to look increasingly parochial… the most optimistic figures I can get to, for Captain Kirk crossing our galaxy, would be 137 years,” Ince writes. “That would be if he maintains a speed of 729 times the speed of light, which is a serious infraction of the laws of physics.”

As well as dealing with some of the biggest topics in life – death, the end of the world, aliens, the concept of reality, the possibility of heaven, the sands of time – the book has plenty of light-hearted moments, including his observation that cricket is the nearest we get to a ball game invented by Ingmar Bergman. But the diverting asides are secondary to what is a serious elegy to the beauty of science. I would also recommend following Ince’s tip to watch NASA’s film Thermonuclear Art, from which, he says, “you will start to get some idea of the perpetual spectacle that makes life on this planet possible”.

The Importance of Being Interested is sparkling. It made my brain throb at times, but also made it buzz.

The Importance of Being Interested by Robin Ince is published by Atlantic Books on 7 October, £17.99

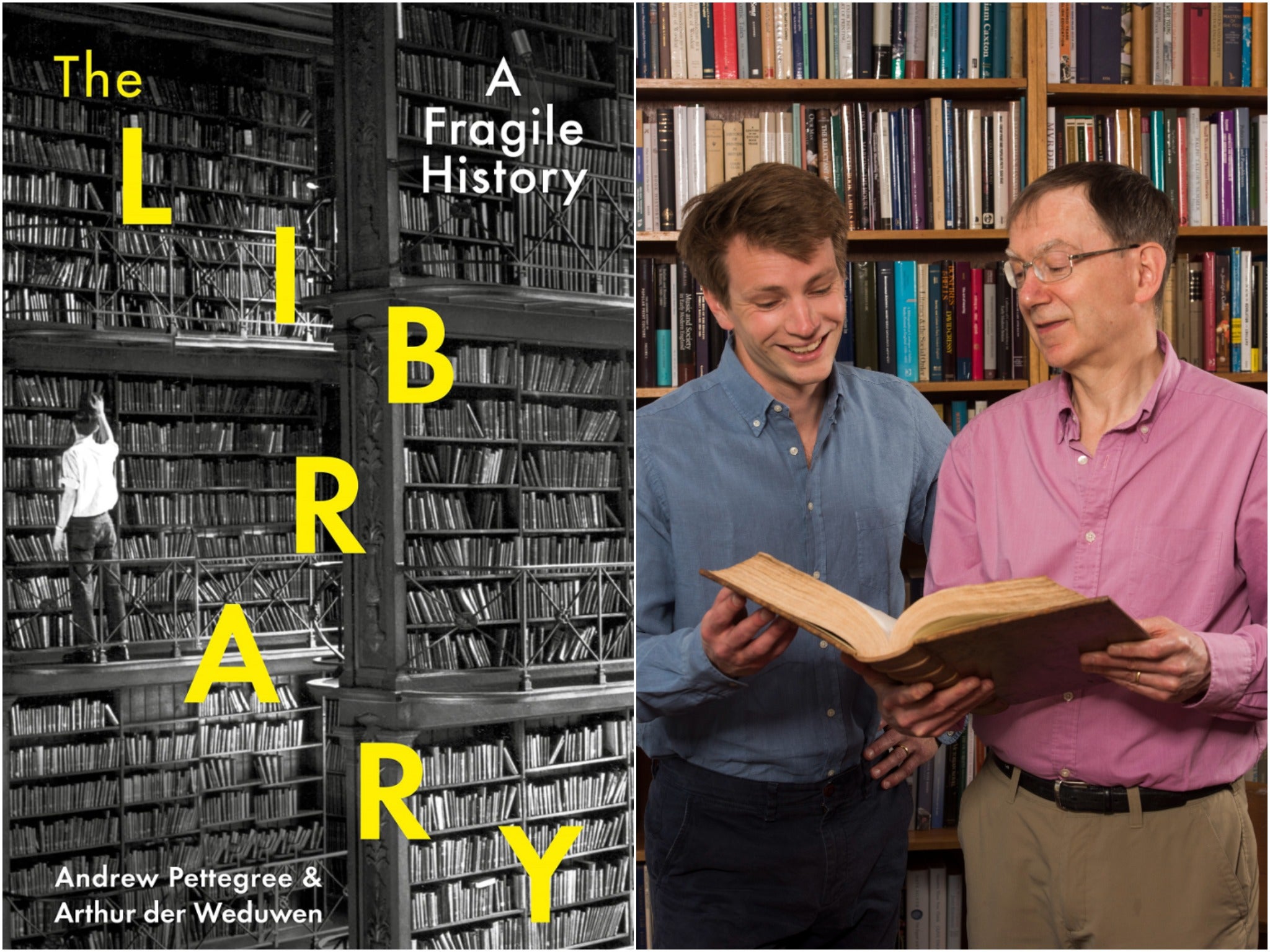

The Library: A Fragile History by Andrew Pettegree & Arthur der Weduwen ★★★☆☆

The memorable cover photograph of The Library: A Fragile History shows one of the large cast-iron book alcoves that lined the main hall of the (long since demolished) Old Cincinnati Library. Times change, of course, and the BiblioTech, in San Antonio, Texas, now houses an all-digital public library, where generation digital come to read on a well-lit array of computer screens. “What has been forgotten here is the young parent taking their infants to the children’s library, where the handling of the books is as crucial to the cognitive development as the texts, or the pensioner exchanging one handful of novels for another,” write historians Andrew Pettegree and Arthur der Weduwen.

I grew up devouring the books from Holborn Library, so it was not hard to find much to enchant in Pettegree and der Weduwen’s empathetic, sweeping history of libraries. The authors convey with real feeling why these institutions have been so central to human culture. This well-researched, intriguing story reaches back to the ancient world and goes on to detail the antiquarians and philanthropists who shaped the world’s great collections. The book reveals some of the crimes committed in pursuit of rare manuscripts. They also deal with the perils and problems for libraries in the modern world.

Libraries are still cherished by some modern governments, fortunately. Library use in France has increased by 23 per cent in the past 15 years – and their government supported 16,500 libraries in 2019, an increase of 400 over the figure recorded two years earlier. In the UK, sadly, it is estimated that more than 800 libraries have closed during the past decade of Conservative rule. It’s a far-fetched hope that our new novel-writing, ostrich anus-eating culture secretary reads this informative love letter to books and begins to even try to genuinely comprehend how wrong it is to destroy libraries.

The Library: A Fragile History by Andrew Pettegree & Arthur der Weduwen is published by Profile Books on 14 October, £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks