Lucian Freud – New Perspectives review: A strangely subdued exhibition

This blockbuster show is out to rescue Freud the artist from Freud the celebrity – but the results are mixed

I’ll let you in on a secret: I’m not the world’s greatest Lucian Freud fan. In fact, to cut to the chase, I can’t stand Lucian Freud. I was prepared to believe the National Gallery’s new exhibition might change that view. But frankly, I wasn’t holding my breath.

His art is grindingly repetitive, with human flesh, clothes, furniture and – always dingy – rooms reduced over decades to the same set of clammy, clay-like textures and brown-dominated colours. It’s safe to say that, as a human being, he’s not my type: a snobbish slummer in low life, and let’s not even start on his attitude to women. But what really gets my goat about Freud is the mystifying regard in which he’s held by the British public. Eleven years on from his death, he’s still endlessly referred to as “our greatest painter” or even “the greatest British artist of the 20th century”. There’s a weird deference in this view, as though being charismatic and posh somehow entitled him to greatness – and being Sigmund Freud’s nephew didn’t do any harm.

We Brits like to think of ourselves as individualistic and creative, with an instinctive for the cutting edge – from The Beatles and the YBAs to grime music. But the popularity of Freud’s fundamentally conservative art attests to the fact that the British are happiest when things are comfortingly old-fashioned. Freud’s take on traditional oil painting comes with a twist, of course: it flatters the viewer into thinking that they’re taking risks, embracing moral discomfort. But the person feeling the moral discomfort should, in my opinion, be Freud himself.

This sizable exhibition offers, we’re told, “new perspectives” on an artist from whom you’d imagine every drop of intellectual value had already been squeezed (an exhibition of his “plant portraits” is opening imminently at the Garden Museum). But let’s keep an open mind.

This show is out to rescue Freud the artist from Freud the celebrity. It wants to steer our attention away from speculating on which of his children, lovers, underworld acquaintances and aristo friends are represented in his portraits, and focus instead on the minutiae of the way they’re painted. It aims to expand our understanding of Freud’s undoubtedly genuine devotion to the Old Master paintings seen in the surrounding rooms.

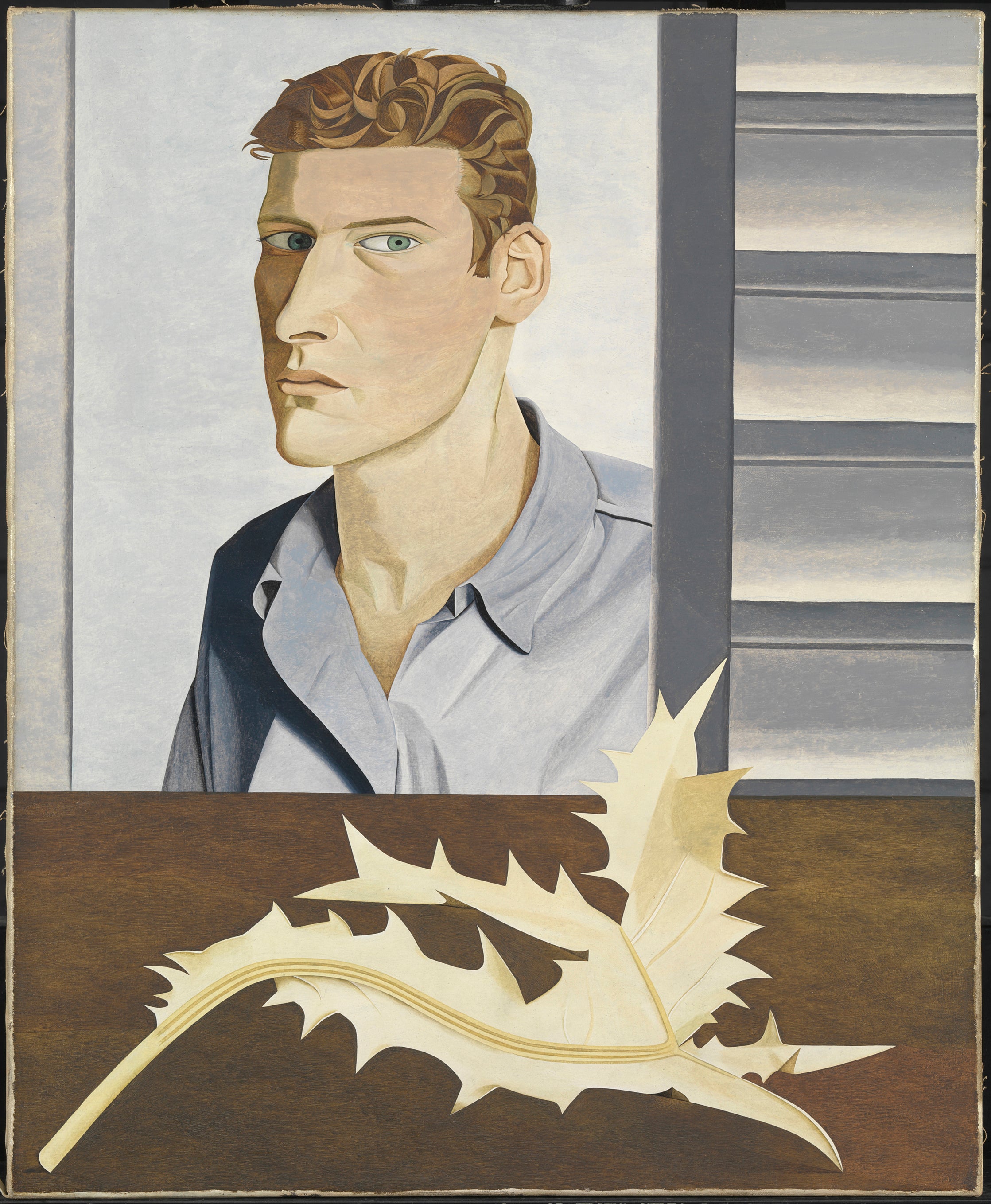

Not even the most bigoted detractor could deny Freud’s remarkable proficiency with the paintbrush, which was evident from an early age. After a roomful of mildly interesting faux-naif paintings created shortly after his family’s flight from Berlin to London in 1933, we’re shown a group of technically impressive paintings done in his mid-twenties. Combining a touch of surrealism with the steely lines and subtly sinister mood of the German New Objectivity artists, such as Otto Dix and Christian Schad, these are works that even people who don’t like Freud’s signature mature work tend to have a soft spot for.

Girl with Roses (1947-8), showing Freud’s first wife Kathleen Garman with deathly pale face and enormous staring eyes, is an undoubtedly striking image, yet it lacks the troubling edge of Dix and Schad’s portraits.

And to show I’m not out to damn Freud in toto, I’ll admit I’ve always thought his portrait of John Minton (1952) comes close to being a masterpiece. The translucent quality of the minutely layered paint and the light reflected in the greatly enlarged eyes enhance our sense of the tremulous fragility that was to drive the depressive painter Minton to suicide three years later. But perhaps the handling of the mouth, and the look of slight toothiness, veer faintly towards caricature. When you’re painting at this level, such details are critical.

From the third room, however, we’re plunged into Freud’s mature style, the painted world that everyone – lover or hater – will instantly recognise as his. From one decade to the next, the palette with its range of browns, ochres, pinks and creams remains constant. Walking between the thematically arranged rooms, you can’t tell from the application of the paint whether you’re in the Sixties, the Eighties or the 2000s, as brush strokes wrap themselves around the facets of form with the feel of some gloopy post-war Cezanne.

The quality of the work, however, certainly does vary. A double portrait of Freud’s fellow painter Michael Andrews and his wife (1969) has a slick caricatured quality. Double Portrait (1985-6), showing a sleeping woman with a greyhound, lacks the sense of tension, or even of a strong relationship between human and animal, that would justify taking on this subject. The dog is meticulously painted, but the woman looks rather half-heartedly bodged in. Naked Girl (1966), however, has a real rigour in the way the planes of the body receding in space are articulated by light, seen against a mass of rumpled sheets. It’s only let down by the head, which feels awkwardly added on, and the features rather crudely daubed in.

The less said of his portraits of the Queen and a military man known as The Brigadier the better. The latter, actually Andrew Parker-Bowles, former husband of the Queen Consort, is seen in an imposing full-length painting designed to update the grand manner “swagger” portrait; it really doesn’t work. And that’s putting it politely. The revelation of this exhibition is how conventional much of Freud’s art is. Portraits of big-wig philanthropists HH Thyssen-Bornemisza(1985) and Jacob Rothschild (1989) feel only a few degrees advanced from stuffy, stodgy Edwardian society portraiture. While you’d expect a degree of conservatism in commissioned images of multimillionaires, Freud’s paintings of pairs of anonymous men – which the exhibition compares to Renaissance “friendship paintings” – often also lack an energising spark.

In Two Irishmen in W11 (1984-5), the uncertain expression of the younger man brings a touch of pathos, but the older figure seated stolidly in the foreground looks simply awkward at being stared at by Freud. A background vista of west London terraces hints at identities for these men in suits – father and son, gangsters, estate agents? – but is probably just the view from Freud’s studio window. The painting’s enigmatic first impression fails to deliver.

Freud was concerned not with “facts”, he claimed, but with a deeper “truth”. The exhibition refers to his “intense gaze”, and writers have waxed endlessly on his “passionate”, “pitiless” and “relentless” inquiry into the nature of ageing and human isolation. Freud spent the best part of 70 years in the studio scrutinising the human figure and face – and I’ve never doubted the guy’s work ethic. Yet the truly hair-raising sense of confronting the “other”, of probing under the skin of the human condition, that you see in the work of Old Masters invoked in the show’s wall texts, such as Velasquez and Goya – and which you occasionally glimpse in the paintings of Freud’s friends Francis Bacon and Frank Auerbach – is rarely evident in Freud’s work; or certainly not in the paintings in this exhibition.

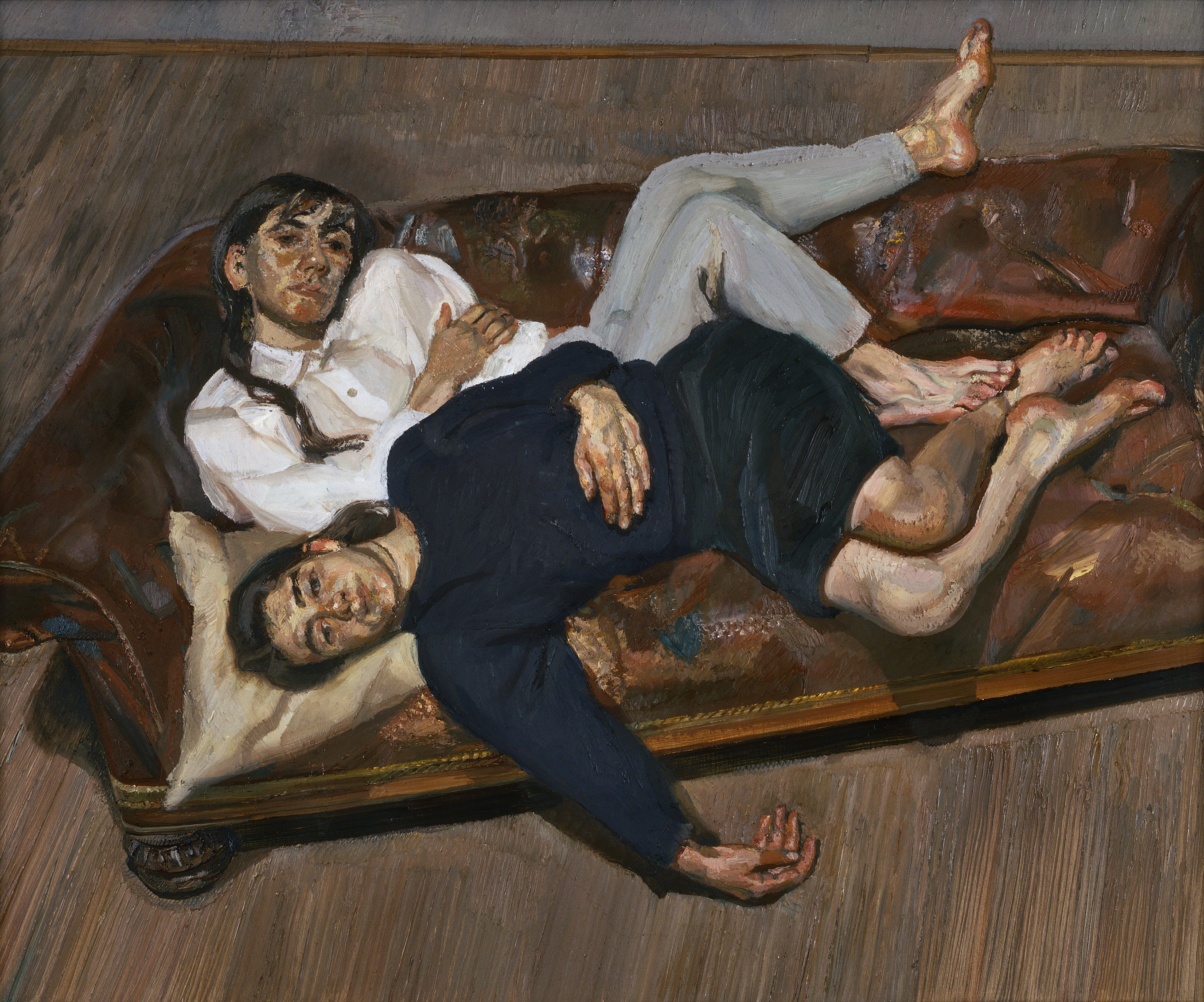

And that’s perhaps because Freud often doesn’t seem to care hugely about the people he paints. The little girl in Large Interior Paddington (1968-9) seems simply present as a visual counterpoint to the large potted plant that dominates the painting. Even when he’s painting his daughters Bella and Esther (1987-8), he seems more interested in the mottling textures of thick paint on their faces than he does in them.

The one subject in which Freud does appear substantially invested is the most important person in his life, his mother. Having spent decades avoiding his adoring mater, Freud produced a large number of portraits of her over the last 15 years of her life. This undeniably important and – from what I’ve seen of it – unflinchingly honest body of paintings, drawings and etchings will hopefully one day be exhibited together. In the meantime, only four examples are shown here. A drawing of Lucie Freud (even their names were the same) on her deathbed isn’t as harrowing as you might imagine. More revealing is Large Interior W9 (1973), which shows his white-haired, stoic mother seated in an armchair with a naked young woman on a bed, only partially covered by a blanket, in the background. Beyond the obvious contrasts of youth and age, and themes of time and mortality, the presence of the young woman seems a deliberate distraction from confronting his feelings about his mother.

The people with whom Freud seems most to identify are the outsider-performer figures who dominate his later works: bald-headed queer performance artist Leigh Bowery and the spectacularly voluminous “benefits supervisor” (as she is always referred to) Sue Tilley.

In Sleeping by the Lion Carpet (1996), Tilley sits naked and apparently asleep with the space in the painting up-tilted so that her massive knees and belly appear to project from the huge canvas. It feels as though she might collapse out of it on top of us at any moment. If Freud apprehends Tilley first and foremost through her billowing flesh, there’s a sympathetic regard in the way he captures not only her crushed and sleeping features but the glow of light on her acres of skin.

I came to this exhibition resenting Freud for the fawning veneration in which he’s held by the British public. I came away feeling almost sorry for him as an artist who didn’t achieve the depth and intensity he might have done and certainly aspired to. This nicely balanced but strangely subdued exhibition will draw in the visitors but I doubt it’ll provide a massive boost to Freud’s slowly and inevitably declining reputation.

Lucian Freud: New Perspectives is at the National Gallery from 1 October to 22 January

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments