Is Les Diaboliques the scariest film ever made?

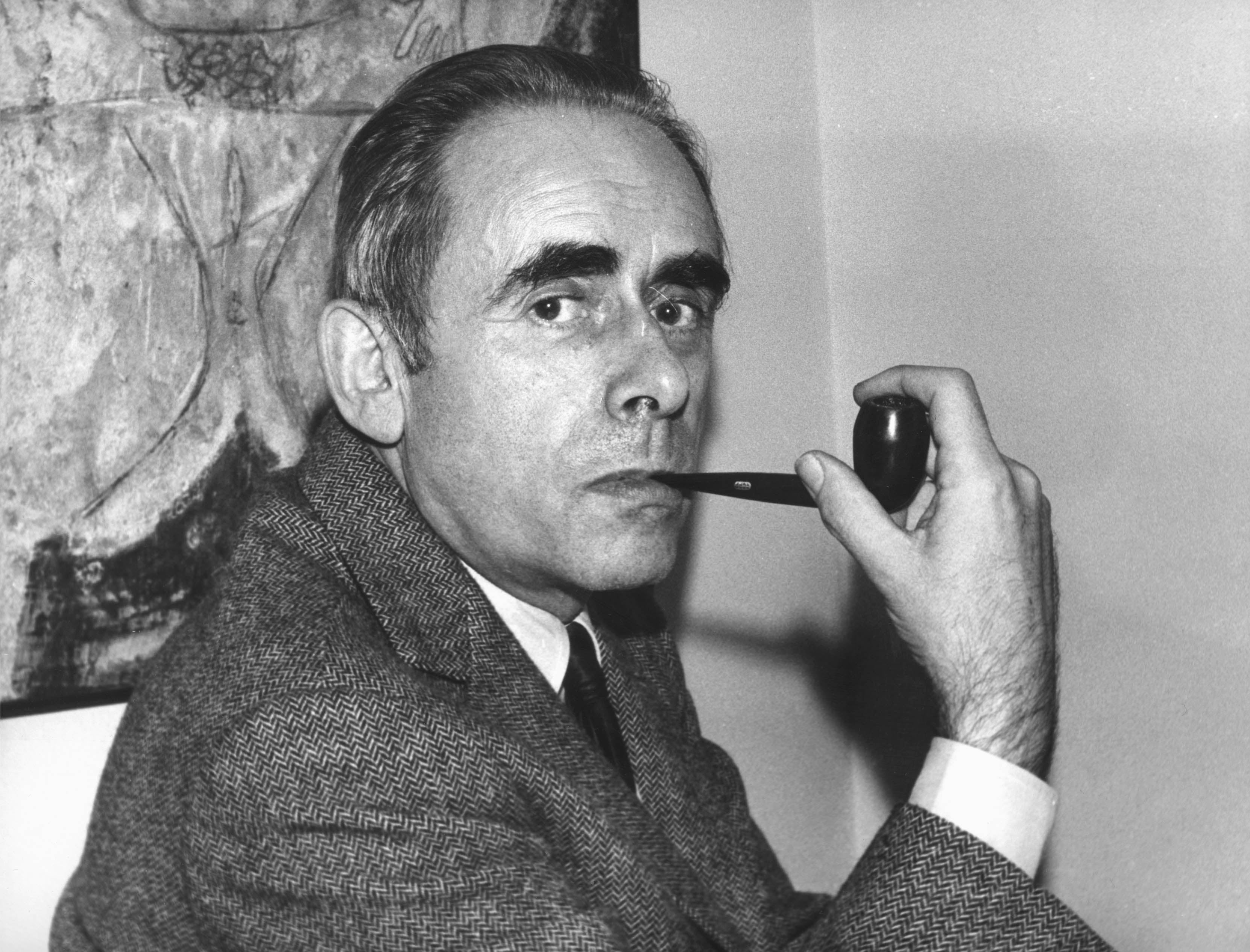

Henri-Georges Clouzot’s chilling classic is screening at the Edinburgh Film Festival this weekend. Geoffrey Macnab investigates why the 1955 film still exercises such malevolent power and looks at how much it has affected modern French thrillers

When French director Henri-Georges Clouzot was making his twisted psychological thriller Les Diaboliques (1955), he wanted the mood on set to be as sour as possible. One ruse he allegedly used was serving his cast members fish that was well past its sell-by date.

It is hard to verify this story but there is an early scene in the film in which the director’s wife is shown on camera ready to gag at the food she is being forced to eat. Véra Clouzot plays the beautiful but sickly Christina Delassalle, the wife of the boorish and bullying Michel (Paul Meurisse), who is the head teacher at a grim French boarding school near Paris. The school is owned by Christina but she is utterly in thrall to her husband. She even puts up with his open affair with one of the teachers, the cynical, world-weary Nicole (Simone Signoret). When very rancid-looking fish is served up for lunch, Michel makes Christina eat every last morsel. “Swallow, swallow,” he commands. She looks fit to vomit but does exactly as she is told.

“One of the most terrifying films ever made,” was how the Edinburgh International Film Festival programmers described Les Diabioliques when they screened it as part of a 2003 Clouzot retrospective. That may be stretching it given that this isn’t strictly speaking a horror picture at all. But what can’t be denied is the film’s extreme creepiness and perversity.

These were qualities that seemed to cling to the director himself. He was a short and unctuous man who had the knack of rubbing collaborators up the wrong way. Brigitte Bardot, who starred in Clouzot’s 1960 film La Verité, described him as “a negative being, at odds with himself and the world around him”. His biographer Christopher Lloyd writes of the way he ingratiated himself with actors and generally extracted very compelling performances from them “but usually at the cost of turning an initially amiable relationship into violent confrontation or icy hostility”.

Clouzot himself led a life blighted by illness and bad luck, one reason why his films take such a dark and misanthropic view of humanity. He knew about betrayal, too. His film career had first begun to blossom in the occupation era, when the French film industry was under Nazi control and he was making films for Continental, the company created by Hitler’s propaganda chief, Joseph Goebbels. After the liberation, Clouzot was banned for four years from working in cinema because of his ties to the Germans.

Les Diaboliques was adapted from the novel She Who Was No More by Pierre Boileau and Thomas Narcejac, the crime writing team whose later book, From Among the Dead, was the source for Alfred Hitchcock’s classic, Vertigo.

The film is famous for its outrageous final reel twist. It has one of the strangest, most jaw-dropping endings in all of cinema. Some critics were infuriated, arguing that such chicanery was close to cheating and invalidated everything that had gone before. “This very ingenuity destroys the psychological realism on which the film’s opening is constructed,” film historian Roy Armes wrote. “The contrivance of the ending renders a second viewing meaningless… and makes Clouzot’s deeply felt black vision seem trite and meaningless.”

An alternative view is that this ending is entirely consistent with the nightmarish logic of rest of the film. It confirms both Clouzot’s deeply pessimistic view of human nature and his macabre sense of humour. The final reel reversal is one of those moments that is both horrifying and absurd. It makes audiences cower and titter nervously at the same time.

Les Diaboliques evokes a world in which everything seems rotten. The school swimming pool, which plays a prominent part in the story, is covered with dirty leaves and scum. The food served to the boys is so disgusting it makes the menu at Dotheboys Hall in Nicholas Nickleby seem like Cordon Bleu cooking by comparison. The school kids (one of whom is played by the youthful future pop star Johnny Hallyday) are wantonly cruel to one another.

The adults are all miserable. The assistant teachers grumble that the wine is both rationed and watered down. Signoret’s Nicole is first seen wearing incongruously glamorous dark glasses –it’s the depth of autumn but she is trying to cover the bruises inflicted by her married lover. “I stumbled getting up,” she explains when she is questioned. Christina cowers like a timorous mouse in the presence of her brutish husband. He isn’t any happier either, desperately short of money, stuck in a dead-end job at a school he hates with a wife he can’t stand and a mistress he seemingly despises.

As the film begins, the two women are planning to kill him. The shy and deeply religious Christina, who has a bad heart problem, isn’t a natural accomplice in a murder plot but sees no alternative.

The genius of Les Diaboliques lies in its combination of the fantastical and the banal. Clouzot makes the setting as drab as possible. There is nothing flashy in the filmmaking style. He takes a documentary-like approach to his material. The school is rundown. Paint is peeling. The skies always seem grey. However, he is probing away at some very dark emotions. Characters continually behave in extreme and surprising ways. A schoolboy will blithely dive into the filthy swimming pool to retrieve keys that Nicole has dropped there. Michel thinks nothing of hitting his wife.

The relationship between the female protagonists is deliberately left ambiguous. In the Boileau-Narcejac novel, the women were lovers. Here, there is a strange intimacy between them but it appears to come from their shared loathing of the man they plan to murder. Signoret’s character is as tough as Véra Clouzot’s is vulnerable.

The director treated his wife off-camera in the same brutal way as her husband did on screen. This was her big break, a leading role, and she was not an experienced actor. Film historian Susan Hayward writes that Clouzot made Véra “work for nine months learning parts from plays she would never act in but which he taped and then used to correct her delivery”.

Véra’s co-stars Signoret and Meurisse were seasoned professionals who didn’t always hide their frustration at her neediness and ineptitude. If she looked pale, cowed and nervous, that was probably how she felt, especially after she had eaten the rotten fish. At the same time, the film can also be seen as a study in male humiliation. The husband is dependent on his sickly wife for money. His belligerence belies his self-pity and insecurity. Whatever the intricacies and reversals in the plot, he is made to suffer extreme physical indignity and pain.

Clouzot takes a ghoulish pleasure in dealing with the mechanics of murder: the amount of poison needed to kill someone, how long drowning takes, and the sheer logistical inconvenience of getting rid of a body – finding the right length of wrapping to conceal it in, a basket big enough to contain it and then having to drive it a long distance in a tiny car.

Les Diaboliques was a box-office hit on its first release but received a muted response from critics, several of whom felt it was trivial and manipulative. However, its influence has been immense and enduring. Even today, all those luridly melodramatic French film and TV adaptations of American writer Harlan Coben novels like Tell No One, No Second Chance and Just One Look have plot twists and moments of Grand Guignol bloodletting similar to those found in Clouzot’s celebrated shocker.

Hitchcock, who was reportedly pipped to the post by Clouzot when he tried to option the novel himself, was a firm admirer. He went on to make his own Boileau-Narcejac adaptation with Vertigo but Psycho also owed an obvious debt to Les Diaboliques. One film had a murder in a bath, the other one in a shower. Both had similar, outrageous plot twists. Hitchcock’s Norman Bates would have fitted very comfortably into the universe Clouzot created here.

The film itself has been remade several times, most famously in 1996 and starring Sharon Stone and Isabelle Adjani. This was a more lurid and conventional affair but with the lesbian romance from the original novel bolted back on for maximum titillation. None of these new versions can match the sheer shock value of the original.

“Don’t be diabolical! Don’t spoil the film for your friends by telling them what happens,” Clouzot commanded the audience in an intertitle at the end of the credits. Sixty-six years later, that order is still being obeyed – one reason why the film still provides such a violent jolt to those watching it today.

‘Les Diaboliques’ is available to watch here on Sunday 22 August at 6pm through the Edinburgh Film Festival

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

0Comments