Books of the month: From Miriam Toews’ Fight Night to Michelle Gallen’s Factory Girls

Martin Chilton reviews five of June’s biggest releases for our monthly column

George RR Martin joked that as much as he loved historical fiction, his problem with it was “that you always know what’s going to happen”. Even when you know the outcome, however, the journey can still be exciting – something true of Louisa Treger’s impressive Madwoman (Bloomsbury Publishing). The novel describes the extraordinary bravery of 19th-century journalist Elizabeth Cochran Seaman. Under the pen-name Nellie Bly, Seaman wrote a blistering exposé of the insane asylum at Blackwell’s Island, a “human rat trap” in which she intentionally got herself incarcerated. Her ordeal makes for a dramatic story.

Another historical novel written with panache is Rebecca Stott’s Dark Earth (4th Estate), the gripping tale of two women who flee to Londinium in 500 AD. It is a novel that puts a female perspective right at the centre of a time period usually dominated by men’s stories. I also enjoyed Natasha Pulley’s The Half Life of Valery K (Bloomsbury), an engrossing novel set in Siberia in 1963. The story was inspired by some chilling real events after the cover-up of a radiation leak.

The tales in Oskar Jensen’s Vagabonds: Life on the Streets of Nineteenth-Century London (Duckworth) confirm that the much-trumpeted “Victorian values” were, in reality, little more than the shameful lack of humanity towards the poor. The book, rich in research, provides a telling account of how, even in death, the impoverished were “chivvied and moved on”. When the rail lines into London’s St Pancras were being laid in the 1860s, tens of thousands of bodies, some of them in freshly dug graves, were “unceremoniously unearthed, jumbled up, indiscriminately buried”. It does at least explain why, growing up in the area, I always felt an eerie Tangina Barrow Poltergeist vibe around the station.

There is plenty of other good modern fiction to recommend this month. Riku Onda’s Fish Swimming in Dappled Sunlight (Bitter Lemon Press) is another original, unsettling psychological thriller, full of dark twists and emotional nihilism, from the author of The Aosawa Murders. The novel, translated from Japanese by Alison Watts, is about a couple who each believe the other to have murdered their guide on a recent hiking holiday.

One of the standout debut novels is James Cahill’s Tiepolo Blue (Sceptre), a coming-of-age tale set in London in the 1990s that deftly explores what it is like to suffer a very public fall from grace.

Finally, in her fluent, potent book of essays, Don’t Let it Get You Down (The Indigo Press), writer and lawyer Savala Nolan offers an insight into modern-day racism including, from her own experience, the way Black women are mistreated by medical institutions in the US.

Novels by Miriam Toews, David Foenkinos and Michelle Gallen, along with non-fiction books about Michael Jackson, bisexuality and life in care homes are reviewed in full below.

Fight Night by Miriam Toews – ★★★★★

Miriam Toews is an outstanding Canadian writer – an adaptation of her novel Women Talking, starring Frances McDormand and Claire Foy, is out in cinemas later this year – and her ninth novel, Fight Night, is a stirring family saga set in Toronto and California.

The three principal characters are nine-year-old Swiv, her pregnant mother Mooshie and her indomitable grandma Elvira (drawn from Toews’ own mother of the same name); the story is told in the unusual form of a book-length long-form letter from Swiv to her absent father, written during a period when her suspension from school has given her precious time with her ailing Grandma. Swiv learns unbeatable life lessons from a joyful force of nature. Elvira teaches Swiv “how to dig a winter grave”, what to glean from watching Call the Midwife, and the importance of Leonard Cohen. Toews exploits the comic exaggeration gained from seeing what adult life looks like to an observant, anxious, humorous child. “I didn’t want to be found passed out on a toilet like a depressed celebrity,” the girl remarks, in one moment of crisis.

Toews grew up in a strict Mennonite sect in Steinbach, Manitoba. As Swiv recounts to her father the stories she hears from Elvira, she inadvertently opens a window to the systematic cruelty, physical and mental, of women in a patriarchal religious society. Willit Braun, the tyrant leader of the church that misused her Grandma, is the seedy villain of the book.

The theme of mental health is also explored in subtle ways that cast a difficult subject in a warming light. Toews, whose father and sister died by suicide, has affecting things to say about how loss alters something in those left behind, how guilt must be shed, and why “we’re all so clumsy in our grief”. Despite all the darkness in Fight Night, the novel is powerfully funny and offbeat.

Although the action centres on the child and her grandmother, the character of Mooshie is also memorable. Lots of things make her flip, including squirrels (“mocking, little vengeful creeps”) or the sort of “timid w***ers” who play mini tennis. Swiv’s mother is described as “the world’s most unstable person”, and when she goes on a “full-on scorched earth” rampage those closest to her know to step back.

The star of the novel, however, is the marvellous Elvira, who radiates compassion, courage and joy. The scrapes she gets into are highly entertaining. There are good running jokes about bowel movements, thongs and ageing. The fateful journey Elvira and Swiv take to Fresno (“raisin capital of the world”) to visit Elvira’s nephews, Ken and Lou, is beautifully crafted.

Fight Night is a celebration of individuality, the will to survive, and the joy and sadness that family life brings. The ending to this superb novel is heartbreaking and heartwarming in equal measures.

‘Fight Night’ by Miriam Toews is published by Faber on 2 June, £14.99

Bi: The Hidden Culture, History and Science of Bisexuality, by Julia Shaw – ★★★★☆

“I wrote this book because this book didn’t exist,” says Dr Julia Shaw, a criminal psychologist at University College London and part of Queer Politics at Princeton University, who is open about her own sexuality after coming out in 2018. “I love being bisexual,” she states simply.

In her well-researched, cogent and compelling book Bi: The Hidden Culture, History and Science of Bisexuality, she achieves her aim of bringing the colourful world of bisexual scholarship “out of the shadows”. Bisexuality, defined loosely as an attraction to multiple genders, was simply denied for most of the 20th century but it’s hard to disagree with Shaw’s assertion that “we centre heterosexuality as the sun of our sexual solar system, blinding our exploration of other sexualities”.

The book offers a serious discussion of important subjects, such as the mental health implications of sexual identity concealment, the problems of stereotyping, and racial and social divisions within the LGBT+ community, along with disturbing sections on corrective rape and conversion therapy. Shaw is always an engaging guide to the landscape, on everything from the hunt for a bi gene to the sexual habits of giraffes and rams.

Shaw evaluates representations of bisexuality in the media and popular culture, from the bi-cliched vampires to serial killer Villanelle in Killing Eve, and questions why it took 89 episodes of Orange is the New Black for the word bisexual to be used, even though lead character Piper proclaims early on that: “I like hot girls, I like hot boys, I like hot people.” Shaw also discusses the misframing of the movie Brokeback Mountain, which is routinely discussed as being about “gay cowboys”. She cites Professor Harry Brod’s contention that the main characters are actually “bi shepherds”.

The book is unlikely to make the shelves of bigoted Boomers, but Shaw has achieved what she set out to do: delivered a book that does justice to the important history of bisexuality.

‘Bi: The Hidden Culture, History and Science of Bisexuality’ by Julia Shaw is published on 2 June by Canongate, £16.99

The Martins by David Foenkinos – ★★★★☆

“Most writers look lecherous or depressed,” says the nameless Parisian author who is the narrator of The Martins, a charming, clever book by acclaimed French writer David Foenkinos (translated by Sam Taylor).

When an award-winning writer is struggling to find inspiration for his new novel, he decides to go into the street and choose the first person he sees to be the subject of his next book. After fate puts octogenarian Madeleine in front of this Parisian author, he gets slowly drawn into the lives of her family: daughter Valerie, son-in-law Patrick, grandson Jeremie and teenage granddaughter Lola.

As well as telling a deft story of family regrets, sorrows and bitterness, Foenkinos astutely explores auto-fiction in a novel that is full of good inside jokes. His characters worry whether their lives will interest his readers. “It was as if my publisher’s marketing director had infiltrated their minds,” quips the narrator, whose life overlaps with Foenkinos occasionally (both suffered from heart disease as teenagers).

The Martins, which explores how people falsify reality to present themselves in a good light, has astute things to say about impatience, 21st-century game shows (which “require a PhD in hysteria”), social media (“Twitter is the indoor equivalent of a cigarette”) and a middle-aged longing for the days before mobile phones, “when you could genuinely disappear from your life”.

The narrator admits to “a depressed man’s sense of humour”, but his outlook is part of why this subtly funny novel acutely captures why “there is something fantastical about ordinary life”. I liked the originality of The Martins and the wonderful punchline about curtains (no spoilers). And, to cap it all, the book is a satisfyingly concise length, unsurprising from a narrator who says: “I don’t like books over 300 pages.”

‘The Martins’ by David Foenkinos is published by Gallic on 16 June, £9.99

I’ll Die After Bingo by Pope Lonergan – ★★★☆☆

There are more than 12 million people aged 65 and above in the UK, and many of what Philip Larkin described as “palsied old step-takers” will end up in care homes on their way down Cemetery Road.

In I’ll Die After Bingo, stand-up comedian Pope Lonergan writes about his decade working in the care sector. His account of care home life will strike a chord with anyone who has experienced this nutty absurdist theatre, as I did with both my late parents. I got flashbacks just reading about out-of-power hoists and drinks with thickening powder.

As well as the brutal, pitch-black comedy – the “wall-to-wall s***”, the patients who drink the shampoo, eat lightbulbs or use an imaginary baton to conduct the dead bees on the windowsill – Lonergan offers numerous touching insights into the sparks of human connection that matter so much when people are trudging along on borrowed time.

Social care is in crisis in the UK, and Lonergan has important things to say about the dumbfounding lack of public attention towards the profession of care employment, an industry served by exhausted, disincentivised, minimum-wage workers and despoiled by the pursuit of financial profit and often run by cold-hearted upper management.

We should all think about why this vital job is devalued by almost every part of society. However, Lonergan is honest about his own problems, including his addiction, and why he left the care sector after occupational burnout. He also does not shy away from the truth that there are also incompetent and “lazy p***ks” working in care homes, who use what he calls the “dump ‘n’ run approach” and those who make snide, cruel comments about residents.

Overall, though, Lonergan is a powerful advocate of why care work is so important and why we need an honest national conversation about the realities of human deterioration and death.

I’ll Die After Bingo by Pope Lonergan is published by Ebury Spotlight on 16 June, £16.99

The Destruction and Creation of Michael Jackson by Ellis Cashmore – ★★☆☆☆

Michael Jackson’s attempt to purchase the skeleton of the Elephant Man from the London Hospital Medical College in 1987 is just one of the many bizarre anecdotes that stack up against the man who was a global superstar.

Details that make Jackson look eccentric pepper Cashmore’s book, The Destruction and Creation of Michael Jackson – including the singer’s “hit list” of enemies which included Steven Spielberg (for refusing to cast him as Peter Pan). Even those who somehow find it possible to defend Jackson against the allegations of sexual abuse of children must surely find it odd that when he married his second wife Debbie Rowe, in Sydney in 1996, his best man was an eight-year-old boy.

However, Cashmore’s book attempts to be more than another rehash of scandals. He discusses Jackson, whom he calls “a bewilderingly complex character”, in light of his role as a “shining symbol of post-civil rights land of opportunity”, and looks at how Jackson’s character was affected by American culture. How much you enjoy the book will depend on your appetite for a philosophical discussion of Jackson and whether you accept sweeping statements such as “white audiences found his flaws reassuring”. There is also some pointless speculation about what would have happened if Jackson had lived beyond 50, or even if he had retired in 1975.

With his drug addiction problems and what seems (to an untrained eye) to be a story of severe mental illness, it is ultimately up to each reader to decide whether they see Jackson’s life as a horror show or sympathise with someone whose friend Jane Fonda called “one of the walking wounded... an extremely fragile person”.

At the time of his death on 25 June 2009, Jackson was midway through sittings for a 10ft-high oil portrait by Kehinde Wiley, inspired by Rubens, which depicts the singer as a 17th-century monarch in a suit of armour, sitting proudly on a white stallion. The painting has a distinct Tony Soprano-Pie-O-My horse vibe, and the illustration captures the grotesqueness of Jackson’s celebrity carnival more succinctly than 360 pages of intellectualising.

‘The Destruction and Creation of Michael Jackson’ by Ellis Cashmore is published by Bloomsbury Academic on 16 June, £19.99

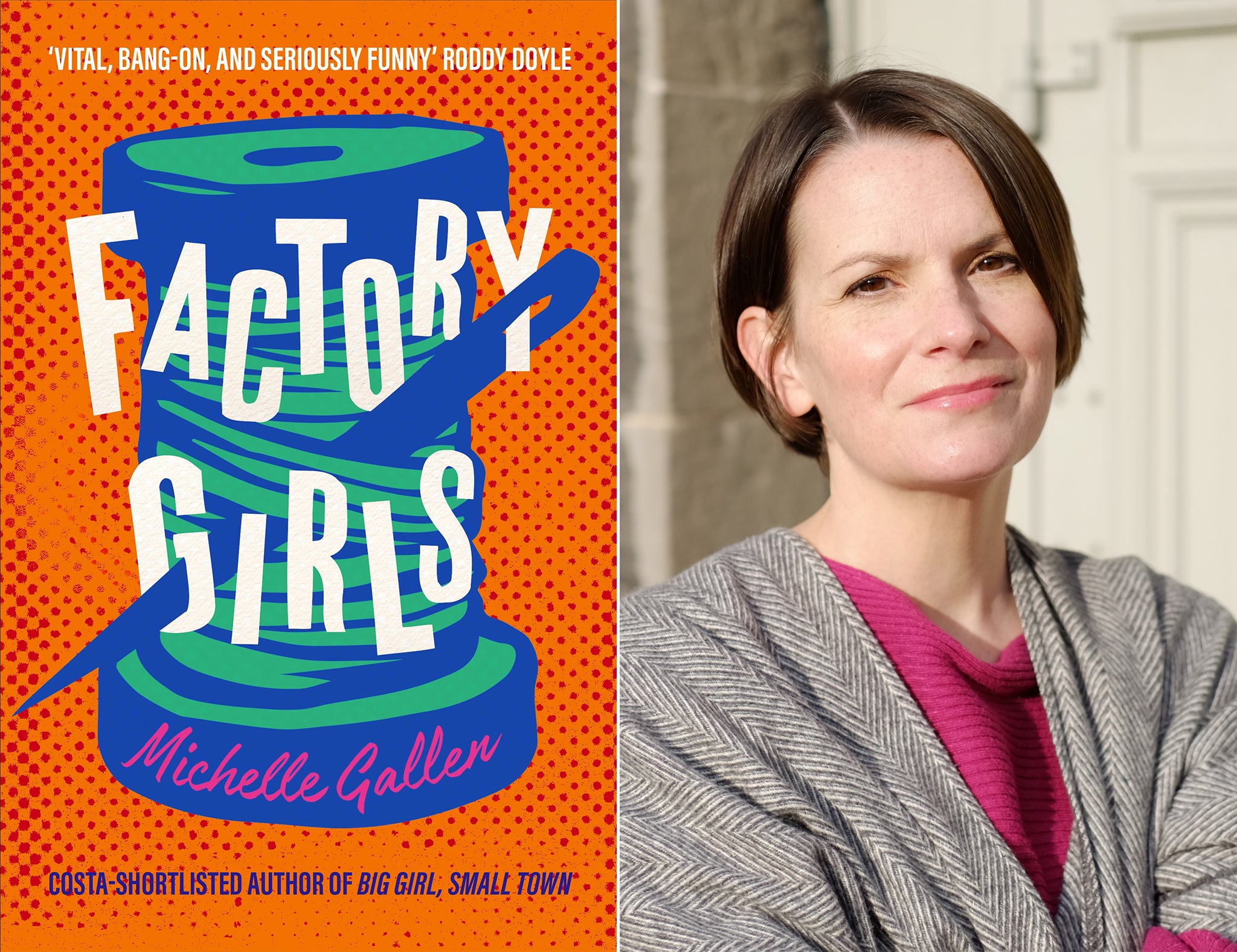

Factory Girls by Michelle Gallen – ★★★★☆

The ups and downs of life for teenagers in a small town on the Irish border is the subject of Michelle Gallen’s highly entertaining novel Factory Girls.

In the summer of 1994, Maeve Murray and her two best friends Caroline and Aoife are waiting for their A-level results, which Maeve hopes will be a passport out of a crumbling Ulster town that is “almost completely segregated” on religious lines. The violence between Catholic and Protestant extremists (The Taigs vs the Prods) is a sinister backdrop to Maeve’s journey into adulthood. In her summer job at the local factory, Maeve sees the tensions start to rise, with little faith in the peace process started by Tony Blair (“the sort of toothy creature you’d see in a Free Presbyterian church”) and genuine fear at the prospect of a terrorist attack.

Gallen, whose previous novel Big Girl, Small Town was Costa Prize shortlisted, offers up scores of funny reflections on everything from an obsession with weather forecasts to the grime of rented flats, from binge-drinking to Jack Charlton’s management of the Irish football team during the World Cup campaign (“sure, he’s as English as genocide”, says Maeve’s ma). The references to events of the early 1990s are sure-footed for the most – such as Liam Gallagher’s music and Eurotrash on television – but I did wonder how many people who aren’t old farts would appreciate Gallen’s joke about Sir Sidney Ruff-Diamond in Carry on up the Khyber.

The minor characters are interesting (especially the pugnacious factory worker Fidelma) and the novel explores the power dynamics and sexism of working life under a predatory boss. The book also crackles with good one-liners. The dialogue and descriptions in Factory Girls are certainly lewd and crude – “Maeve didn’t like sitting on Nana Jackson’s bed – she’d a fear that the old-lady smell would seep into her knickers and shrivel her flaps” is just one example– yet this earthy comedy also has telling things to say about violence and division.

‘Factory Girls’ by Michelle Gallen is published by John Murray on 23 June, £16.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks