Indiana Jones 5: Is it really over for Harrison Ford as an action star?

As Ford claims it’s his final outing as the kick-ass archaeologist, Geoffrey Macnab looks back over his career and says the action star knows it’s the perfect time to call it quits

This is it!” Harrison Ford told an adoring audience last weekend about throwing the towel in as Indiana Jones. “I will not fall down for you again.” He had just introduced a new trailer for Indiana Jones 5 at the D23 Expo, a Disney fan event held in California – the film is yet to receive its official title and won’t be in cinemas until next summer. He was standing alongside Fleabag’sPhoebe Waller-Bridge, who plays his goddaughter, and the film’s director, James Mangold.

It’s been 14 years since the last Indiana Jones movie was released, Indiana Jones and the Kingdom of the Crystal Skull. Just like its predecessors, the new movie promises to be rip-roaring fare with explosions, chases and conspiracy aplenty. The supporting cast looks very impressive: Antonio Banderas, Mads Mikkelsen, Toby Jones and Waller-Bridge are all along for the ride as the kick-ass archaeologist goes in search of Noah’s Ark.

It is easy to understand why Indiana Jones’s latest adventure is already provoking such a nostalgic response so many months in advance of its release. It marks both its octogenarian star’s comeback and his farewell as an action star. After this last adventure, there will be no more cracking the bullwhip or running away from boulders, or venturing inside Temples of Doom. This isn’t Ford’s retirement. He’ll soon be seen opposite Helen Mirren in a 1920s-set prequel to the TV series Yellowstone – but it is the last time he’ll be performing those harum-scarum big screen stunts everyone loves him for.

The prospect of signing off as Indiana Jones seemed to choke up Ford himself. His voice wavered and he pointed to his heart as he talked about the new movie.

As it was reported in the media that Harrison Ford was “holding back tears” and “emotional” at D23, the surprise was obvious. Ford has lasted at the top of the Hollywood A-list for 50 years without ever previously showing any outward sign of sentimentality in public. That is one of the reasons audiences cherish him. He’s one of those craggy, old-style Hollywood figures who tend to keep their feelings firmly in check. In interviews, he is dry, very deadpan, and rarely gives much away.

“He guards his private life with a passion bordering on the obsessive,” one biographer complained about the movie star who was nicknamed “Mr Mum” by the media. Nonetheless, here he was, tremulously holding forth about a role that clearly means far more to him than just another pay cheque, and that will put the seal on one of the most astonishing careers in recent Hollywood history.

It would be a mistake to call Ford an accidental movie star. He set out very deliberately as a young man to become an actor and headed to Los Angeles in pursuit of his dream. His films, according to Box Office Mojo, have now made an astonishing $5.5bn in North America alone, a higher figure than Tom Cruise has achieved. Nonetheless, his progress through the film industry has always had a haphazard quality.

When Ford first arrived in town in the late 1960s, Columbia Studios dismissed him from their talent development programme because he “lacked star quality”. By then, he had a family to support and so made his living as a self-taught carpenter instead. The way the hand-carved anecdotes come down is that he landed his breakthrough roles by chance, largely because he was employed as a tradesman by film industry clients who, at the time, were struggling to cast their movies. He had been doing work for executive Fred Roos who felt he might be a good fit as the charismatic hot rod racer in George Lucas’s American Graffiti (1973).

In his biography of Lucas, author John Baxter writes about Ford’s unwillingness to take the role. The pay was $480 a week and he was already making twice that amount for his carpentry work. Roos, therefore, bumped up his salary.

In his cowboy hat and with an arrogant grin on his face, Ford was cocksure and looked altogether more mature than his co-stars. By then, he was 30 after all. It was a striking performance in a role that was little more than a cameo. Nonetheless, he was soon busy again with the clamps, drills, hammers and saws. His woodworking skills provided a more reliable way of making a living than appearing in front of the cameras.

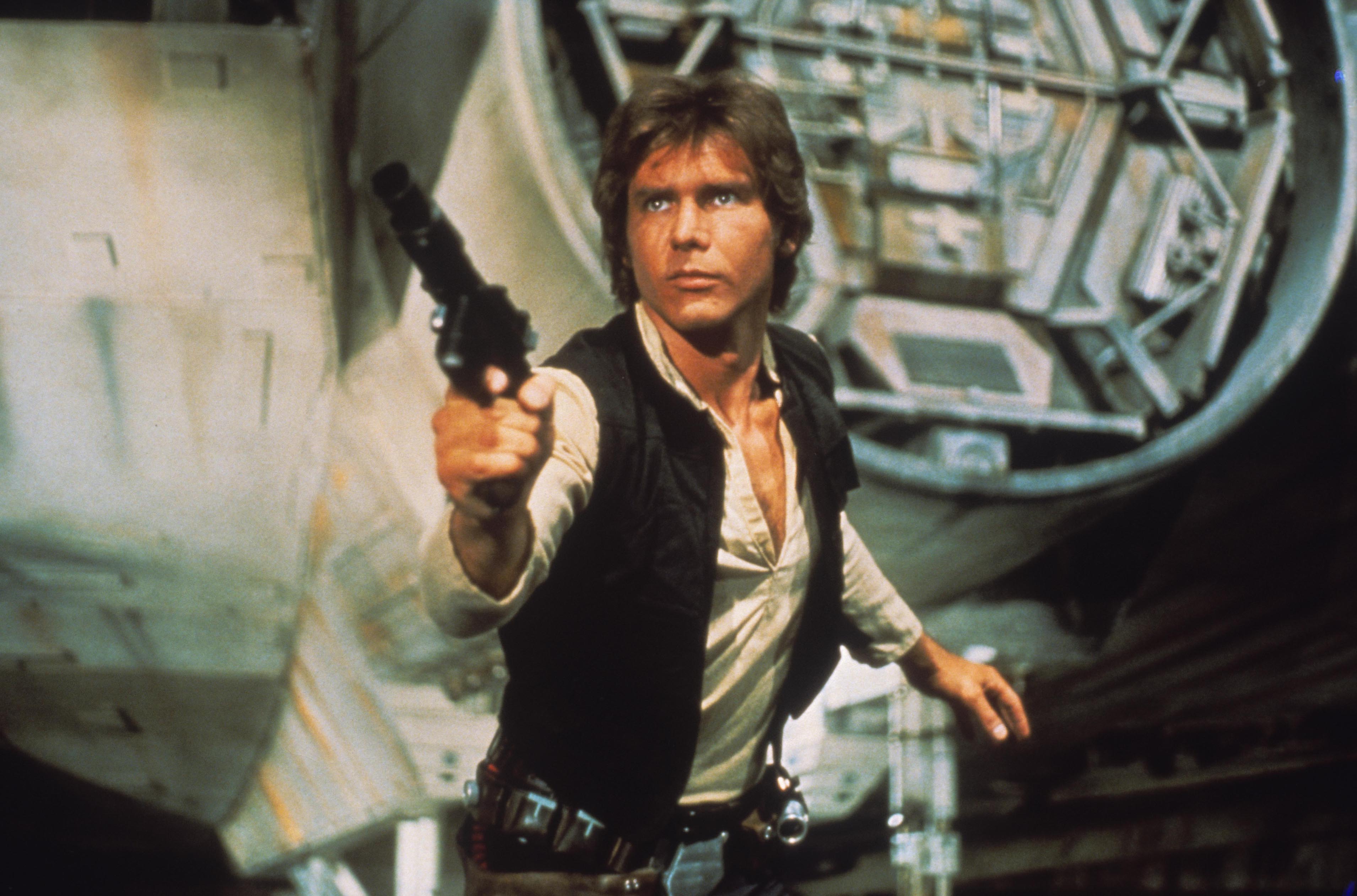

“I was working on an elaborate portico entrance to Francis Ford Coppola’s offices, working as a carpenter, when George [Lucas] walked in with Richard Dreyfuss to begin the first of the interviews for Star Wars. Somehow, that rang a bell with George and I became eventually Han Solo,” Ford explained in a typical matter-of-fact fashion to Vanity Fair about how he came aboard one of the biggest movie franchises in cinema history. He hadn’t actually been canvassing for the part but, typically, got it anyway.

It was a similar story with Raiders of the Lost Ark. Steven Spielberg and Lucas had already offered Indiana Jones to Tom Selleck but he was too busy playing the detective hero in TV’s Magnum PI. By then, the production was only a few weeks away from shooting. It was time, again, to turn to the master carpenter.

Whereas other newcomers might have seemed overwhelmed at the huge opportunities being given to them, Ford took the roles in his stride. “George, you can type this shit but you sure can’t say it,” he is alleged to have told Lucas, who was two years younger than him, after reading the dialogue in the Star Wars screenplay.

Ford had traits that were very contradictory. On the one hand, he possessed the brashness and defiance that characterised method-style screen rebels like James Dean or Marlon Brando. On the other, he was thoroughly dependable – the type who’d always complete any job he started. There was nothing neurotic about him. He had an everyman quality that, in later years, would qualify him to play presidents and professors, as well as action heroes. Like Henry Fonda in The Grapes of Wrath, he is someone viewers instinctively trust. Whether he is sitting in the cockpit of a spaceship making small talk with a hirsute friend like Chewbacca in Star Wars or dressed in a suit as a Wall Street executive opposite Melanie Griffith and Sigourney Weaver in Working Girl (1988), he always seems authentic and at ease.

Another side of Ford’s personality that perversely attracts fans is his curmudgeonly quality. In interviews and on screen, he can often seem very bad-tempered indeed. Acting mean, though, has its benefits. As he has grown older, Ford may have lost his athleticism but he can still scowl with the best of them. It’s instructive to watch him as the Scrooge-like TV newscaster Mike Pomeroy, reluctantly revealing his “fluffy” side in Roger Michell’s underrated romantic comedy, Morning Glory (2010). Pomeroy takes himself very seriously. He has reported from every foreign war going and has a nose for hard news.

“I’ve won eight Peabodys. A Pulitzer. 16 Emmys. I was shot through the forearm in Bosnia. Pulled Colin Powell from a burning Jeep. I laid a cool washcloth on Mother Teresa’s forehead during a cholera epidemic. I’ve had lunch with Dick Cheney,” he says, laying out his credentials. The veteran anchor reacts very badly when he ends up, for contractual reasons, co-hosting a Richard and Judy-style breakfast show devoted to showbiz gossip, chit-chat about the weather, and cooking. Ford shows a gruff malice that even Bill Murray would struggle to match. He bullies and exasperates the show’s producer – played by Rachel McAdams. We know, though, that he will reveal his inner decency in time for the end credits.

There has often been a little Pomeroy in even Ford’s most conventional leading man roles. Think of him playing Indiana Jones for the first time in Raiders of the Lost Ark in that famous scene in which he takes on the swordsman. The swordsman twirls his blade extravagantly. We expect Jones to use his bullwhip against him but, instead, with a look of haughty disdain that shows he doesn’t have time for such tomfoolery, he pulls out a gun and shoots the man instead.

“We like our men like we like our coffee – hot, grumpy and named Harrison Ford,” is the catchline for The Fordcast, a podcast in honour of the actor, which ran for more than 50 episodes and dissected his career in the minutest detail. Lauren Milberger, who created the podcast together with Rachel Leishman, was one of the many young fans who grew up with a poster of Ford as Indiana Jones in her bedroom.

“If you grew up at a certain time in the world, or the United States, he [Ford] was a big deal,” Milberger tells me. She has seen “99 per cent” of the films and TV shows that the actor has made. “There are some of his television appearances that I don’t think can be found,” she says of the missing 1 per cent.

As for Ford’s grumpiness, she suggests it is partly put on. “You can sometimes keep your privacy if you have a bit of a persona that is stand-offish.”

Ford, Milberger believes, is far more versatile than his reputation as the rugged all-American hero suggests. “Harrison Ford wanted to be a character actor but, at every step of the way, the audience or producer said, ‘No, no, no, you’re a handsome action star’.” Ford, therefore, started “sneaking” idiosyncratic elements into characters who seemed bland and one-dimensional on the page. For example, he showed up on set for the thriller Presumed Innocent (1990) with a deliberately terrible haircut while insisting on having a beard for the opening sequences of The Fugitive (1993).

It is revealing to watch him in Wolfgang Petersen’s Air Force One (1997), in which he played a fictional US president. In the early scenes, he is authoritative and statesman-like but the moment his wife and daughter are put at risk, he immediately shows his inner Rambo.

Like James Stewart in his films with Alfred Hitchcock, Ford also excels in playing men under sudden and extreme stress. He was excellent as the surgeon whose wife is kidnapped in Roman Polanski’s Frantic (1988) and as Richard Kimble, the wrongly accused man on the run in The Fugitive. He played Deckard in Ridley Scott’s sci-fi detective classic Blade Runner (1982) with a mix of brutality and yearning that evoked memories of the best private eyes in Hollywood film noir.

Ford is expert at going against the grain. He brings a soulful quality to his action roles and a sense of mischief to his more strait-laced characters. He is one of the biggest movie stars of his era and yet seems very down to earth. He may be a top movie star but there was a period when he seemed to be in the press more often for having mishaps in small planes he enjoyed flying than for appearing in blockbusters.

Podcaster Milberger recalls her astonishment at recently meeting a young Marvel fan in his twenties who had never heard of Ford. This may be incomprehensible to Star Wars and Raiders of the Lost Ark fans but it reflects the fact that Ford has hardly been seen in movies in recent years. Now we are going to get the last sight of him as Indiana Jones – and what might be our very last sight of him on the big screen.

“It’s not the years, honey, it’s the mileage,” Indiana Jones quipped in Raiders of the Lost Ark about growing old. It’s one thing playing an archaeologist and another looking like something he has just dug up. Ford is the most enduring and best-loved matinee idol of his era, but he knows that now is the perfect time to call it quits in action movies.

‘Indiana Jones 5’ is due to be released on 30 June next year

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments