Groucho Marx’s darker side is being brought back to the movies – but wouldn’t we rather see him making us laugh?

After the announcement that Geoffrey Rush is starring in a new biopic, ‘Raised Eyebrows’, about Groucho Marx in his declining years, Geoffrey Macnab looks back on what made him one of America’s greatest comedians

When he was riled, the comedian Groucho Marx would resort to extreme measures. After the salacious gossip and scandal magazine Confidential wrote an intrusive story about his private life, he responded by firing off a severe letter to the editors: “Gentlemen: if you continue to publish slanderous pieces about me, I shall feel compelled to cancel my subscription.”

Once Groucho was asked for his opinion about a Broadway show he hadn’t much enjoyed. What did he think? “I’d rather not say,” he replied. “I saw it under bad conditions – the curtain was up.”

This, then, wasn’t a man to take lightly. He was indeed seriously funny. His image endures. All a cartoonist needs to evoke Groucho is a moustache, a cigar and a pair of spectacles. Some of his one-liners have outlived him, too. “I wouldn’t want to belong to a club that will have me as a member,” is one piece of Marxian wisdom still often cited today.

Some 45 years after his death, Groucho (1890-1977) will soon be back on screen. Oscar-winning Australian star Geoffrey Rush has signed up to play him in Oren Moverman’s new biopic, Raised Eyebrows, based on Steve Stoliar’s memoir, Raised Eyebrows: My Years Inside Grouch’s House. Sienna Miller is co-starring as Erin Fleming, the younger woman who became Groucho’s secretary, companion and manager – but was later accused of embezzling from him. Outside her relationship with Groucho, which is believed to have been platonic, Fleming is best known for her cameo in the 1972 comedy, Everything You Always Wanted to Know About Sex* (*But Were Afraid to Ask), which was directed by fervent Groucho Marx fan, Woody Allen.

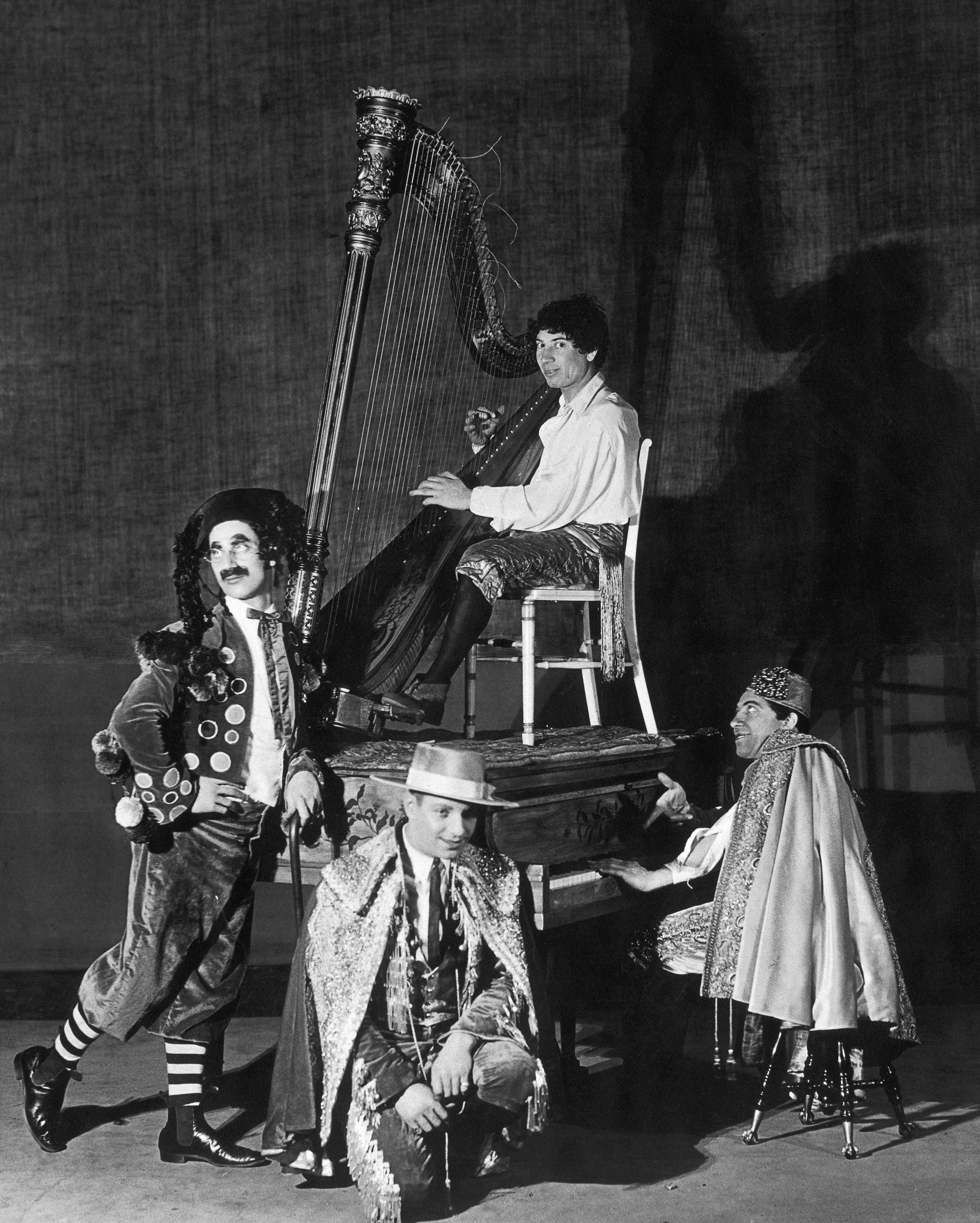

The project, which will be presented to potential distributors and financiers in Cannes next week, tells of how a starstruck young Marx Brothers fan went to work for Groucho as his personal secretary during the comedian’s final years in the early 1970s. Stoliar had grown up watching the films made by the siblings (Zeppo, Harpo and Chico as well as Groucho) who had been among the most popular comedy stage acts in America in the 1920s before becoming equally big in movies during the early talkie era.

Rush, who played another equally complex and mercurial figure in The Life and Death of Peter Sellers (2004), is still the actor filmmakers turn to first when they want to tell multi-layered stories about troubled comedians. It remains to be seen, though, whether he will be able to capture the quicksilver charm that Groucho showed on screen. The comedian in the book Raised Eyebrows is a mere husk of the figure that fans remember from films and TV shows. By the time Stoliar met him, Groucho was already in his eighties and in very poor health. Traces of his old wit remained but he was physically and mentally frail. His brothers had died and his old friends were passing away one by one. He’d even had to give up his cigars for health reasons.

Director Overman told trade paper Deadline how “excited” he was about “bringing Groucho back to the movies”. However, it’s a very morbid way to get him back on screen. Most fans would far, far rather see him in his wisecracking pomp than as a sickly old man in his declining years.

The New York-born comedian was witty, acerbic, quick on his feet and always ready to ad lib – one reason why he enjoyed a successful late career on radio and TV quizzes and chat shows long after all those Marx Brothers movie classics had stopped being shown in cinemas.

Groucho and his brothers were pushed into showbusiness by their mother. They began their careers primarily as vaudeville singers. In 1912, their performance at the Opera House in Nacogdoches County, Texas, was interrupted by a man running into the theatre, shouting about a runaway mule and creating a huge commotion. Everyone seemed far more interested in the mule than they were in the performance on stage. The brothers were so exasperated that they started haranguing the spectators. It was when the spectators began to laugh that they realised that they might have stumbled on comedy gold.

Groucho was the driving force when it came to the siblings creating comic mayhem. He was also a complex and contradictory man. In the early 1960s, he corresponded with the author and poet TS Eliot. The patrician writer of The Waste Land and the Jewish comedian had a strong mutual admiration in spite of coming from such radically different backgrounds – and in spite of Eliot’s anti-Semitism.

Author Lee Siegel claimed that the comedian would far rather have been a literary figure than an entertainer. “Groucho was driven by shame about his lack of formal education, having dropped out of school in the seventh grade. He had also been traumatised by catching gonorrhoea from a prostitute while on the road at the age of 15,” Siegel wrote about him.

Groucho may not have been to college but he was smart and had a love of words. His repartee enabled him to duck personal prying. It was a way of deflecting attention. “Groucho” wasn’t his real name (he was actually called Julius Henry Marx) but was a key component of his carefully constructed comic persona. Even his moustache was painted on. In one of the great metamorphoses in US showbusiness history, the boy who had grown up in relative poverty in a crowded household on New York’s Upper East Side somehow managed to transform himself into the urbanely subversive, wisecracking figure who runs amok in the Marx Brothers movies. Groucho was the son of a tailor whose income, as he wrote in his autobiography, “hovered between 18 dollars a week and nothing.” He, though, became a millionaire.

There was a devilish relish in the way Groucho used to torment the matronly Margaret Dumont in those classic Marx Brothers movies, like a quick-witted fisherman harpooning a whale. “He developed the insult into an art form,” The New York Times wrote in its obituary of the comedian. Whenever he encountered anyone pompous, his immediate instinct was to go on the attack. His humour, though, was never really cruel – or, at least, it never sounded cruel. He’d make outrageously offensive remarks in a blandly understated, throwaway fashion that obscured their meaning. With his raised eyebrows and half-smile, he always seemed more benign than malicious.

In the late 1960s and early 1970s, during the counterculture era, the Marx Brothers enjoyed a revival as a younger generation warmed to their offbeat humour and irreverence. They had an appeal that other screen comedians from the golden age lacked. You’ll find none of the sentimentality in A Night at the Opera or A Day at the Races that some viewers find hard to stomach in, say, Charles Chaplin’s work.

Groucho’s reputation as one of America’s greatest comedians still endures. However, the Marx Brothers’ films have slipped from view. They’re not shown on mainstream TV as frequently as they once were. Their anarchic surrealism ought to chime with viewers today. Groucho’s relentless anti-authoritarianism will never date. Nonetheless, the films have elements that might make contemporary audiences uncomfortable. Harpo Marx, who never speaks on screen, may look beatific when he is playing the harp but he also behaves a bit like a sex pest, chasing women around while hooting a horn at them. Groucho’s innuendo-ridden one-liners don’t go down as easily as they once did. “But that’s bigamy,” he is told when he proposes marriage to two women at once in Animal Crackers (1930). “Yes, and it’s big of me too. It is big of all of us. Let’s be big for a change!” he instantly replies.

The glory of the Marx Brothers, though, is that they are both goofy and sophisticated, innocent and risqué. Their movies are full of very funny, very juvenile, slapstick but they also have storylines and gags written by such respected authors and humourists as Pulitzer Prize-winning playwright George S Kaufman and the Oscar-winning SJ Perelman.

Geoffrey Rush in Moverman’s new movie is bound to show the darker side of the comedian – the anguished, conflicted man behind Hollywood’s most famous moustache – but if the new film reminds audiences even a little of Groucho’s genius, that’s a good enough excuse for it to be made anyway.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments