Devoted, humble, kind: Why François Truffaut and his work should never be forgotten

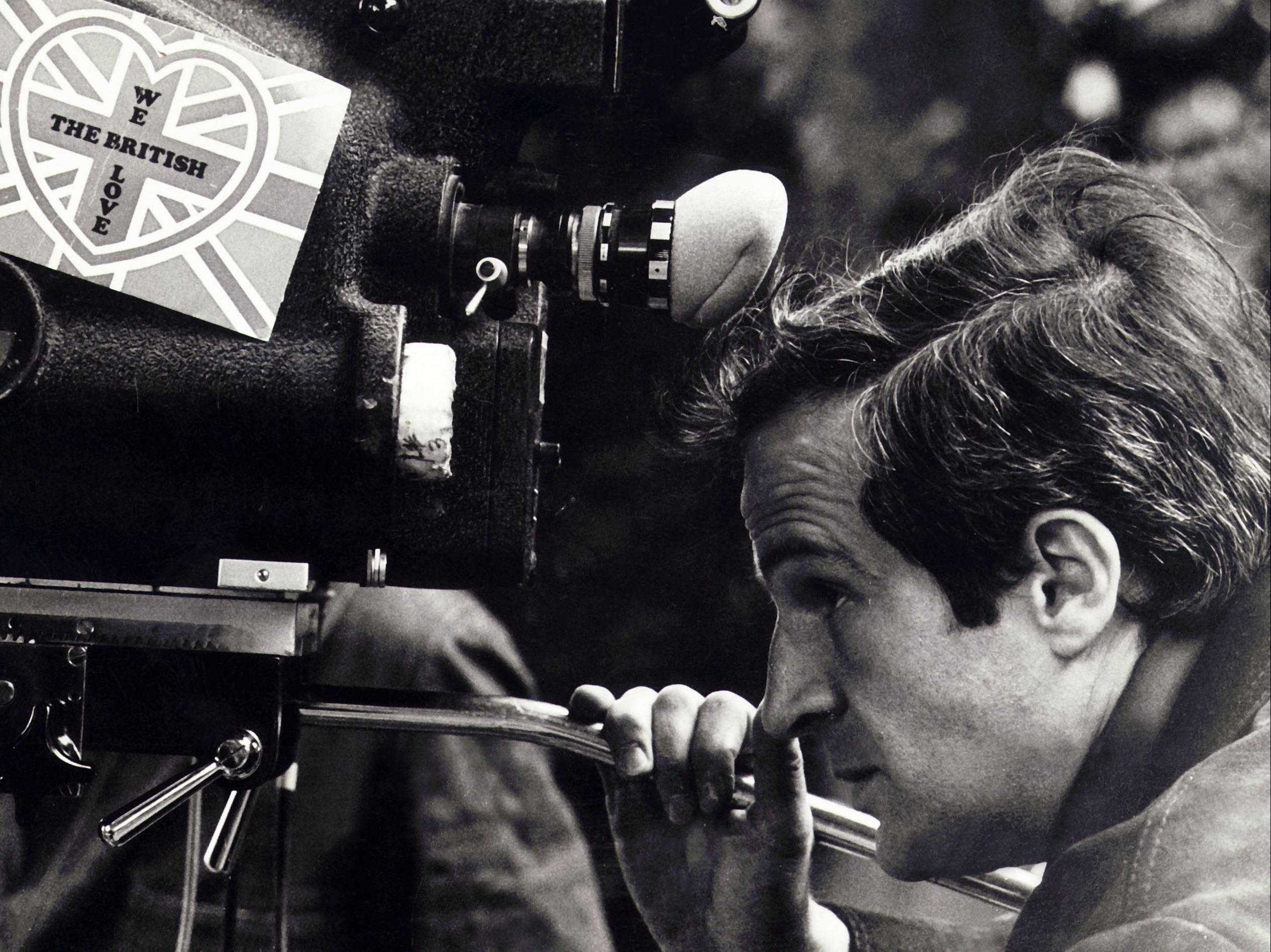

Ahead of a major BFI retrospective of Truffaut’s films, Geoffrey Macnab looks back on his career, and wonders how the French New Wave director seems to have fallen out of vogue

He really liked women – a lot. Not all directors like women. Sometimes, they really don’t do you justice,” Jacqueline Bisset says of the French filmmaker François Truffaut, who directed her in the Oscar-winning 1973 film Day for Night.

Truffaut (1932-1984) is the subject of a major UK-wide BFI retrospective starting in January. Several of his films will be rereleased. The season will provide a chance to re-assess a director who, close to 40 years after his death, has fallen strangely out of vogue. Today, in the UK, very little of his work is in circulation.

The season is programmed in four themes: The Antoine Doinel Cycle (looking at the series of autobiographical films he made throughout his career with Antoine as his alter ego), The Renoir Truffaut (exploring the influence of Jean Renoir on his work), The Literary Truffaut and The Hitchcock Truffaut. There isn’t, however, a section on Truffaut and women. Nor is there one on Truffaut and children. Arguably, they were the real key to his work.

And the cats, of course, but more on that later.

Day for Night is a movie about the making of a movie, set in the famous Victorine Studios in Nice. The film within the film is a full-blooded Gallic melodrama in which a young woman (Bisset) runs off with her husband’s father. The real action, though, is all happening behind the scenes. Truffaut himself plays the director, gamely trying to hold the whole circus together. Bisset’s character is the British movie star, Julie Baker, who has just had a nervous breakdown and, for good measure, has recently married a man very much older than herself.

“It was quite confusing because we would not know when he [Truffaut] would say ‘cut’ whether he was playing the character or he was being himself,” Bisset tells The Independent. She and the other cast members struggled to distinguish between the different levels of reality on the set. At times, they didn’t know whether the cameras were rolling or not.

Bisset also talks of Truffaut’s kindness – not a trait associated with many other filmmakers of his stature. “I never saw him raise his voice to anybody,” she says. “He was… nice! He had a sense of life. He liked to enjoy himself.”

There is a moment in Truffaut’s 1976 feature, Small Change, which sums up perfectly his humanistic approach to filmmaking. A toddler is shown crawling along a windowsill high up in an apartment building, in pursuit of a kitten. Of course, the baby falls. Miraculously, though, the little tot lands softly and unharmed.

It’s unthinkable that any of Truffaut’s contemporaries in the French New Wave would have countenanced such a clichéd and mawkish scene. If Jean-Luc Godard had been directing, the toddler would almost certainly have gone splat. That, though, wasn’t Truffaut’s way. In the context of what is otherwise a realistic film, the scene is completely out of place but also redemptive and magical.

Truffaut himself had a famously unhappy childhood, dramatised in his debut feature The 400 Blows. His mother ignored him. His beloved grandmother passed away when he was still a kid. (In the film, Antoine plays truant from school and lies that his mother has died.) As an adult, the director became an impassioned advocate for children’s rights. “An unhappy adult can start again from scratch. But an unhappy child is helpless,” a teacher tells his class at the end of Small Change. “Of all mankind’s injustices, injustice to children is the most despicable.”

These are the moments in Truffaut movies that cause some movie critics acute discomfort. You don’t expect the young revolutionary of Fifties and Sixties French cinema to take a Dickensian view of childhood. After all, he was the radical Cahiers du Cinema critic who got banned from the Cannes Film Festival for being so outspoken. He famously skewered the old guard of French cinema in his 1954 essay, “A Certain Tendency in French Cinema”. It was there he wrote with such withering disdain of the “Tradition of Quality” in all those “insipid” and “timid” literary adaptations that French cinema was then making.

Truffaut was contradictory in more ways than one. He was behind the so-called “politique des auteurs”, the dogmatic creed that directors, even those working in the studio system, were the true creators of their work. But Day for Night hardly makes much of an argument for auteur filmmaking. The director’s job, as Truffaut shows it, is one of crisis management. It’s all about dealing with pregnancies, affairs and bereavements among his cast and crew. In the film, the stunt artist runs off with the script girl. The male lead (Jean-Pierre Léaud) has just been abandoned by his girlfriend. The script isn’t complete. The unions are causing trouble. Truffaut is shown always in the middle of all the chaos. He’ll hold actors’ hands and touch their faces, as if he believes he can mould their expressions into the ones he wants.

Then there’s the scene, which plays like something out of a cat lover’s YouTube channel, in which the filmmakers attempt to shoot a kitten sipping from a saucer of milk. The small creature turns out to be even more skittish and unreliable than the actors. You can understand why Godard despised Day for Night. He and Truffaut had been comrades in arms during the heady days of 1968. But now, Truffaut was making the equivalent of viral pet videos.

That, though, is the paradox about the French filmmaker. He was at once the rebellious iconoclast of post-war European cinema and a director who made very audience-friendly, even mainstream movies, often with a self-consciously literary feel. His autobiographical Antoine Doinel cycle began in angry, combative fashion with The 400 Blows but the later films were far more whimsical and playful.

Posterity offers two competing versions of Truffaut. One is the earnest cinephile, devoted to Hitchcock and Orson Welles, who had a Jesuit-like devotion both to cinema and to literature. “His lack of interest in food which is in the movie Day for Night, when he says, ‘Why would we go and eat there when we could have a sandwich round the corner from the cinema,’ that was very much him,” Bisset reflects on how he would always put movies above everything else.

The other Truffaut was the “humble,” solicitous figure who made everybody on set feel at ease. One friend described him as “a treasure trove of kindness”, not a description that you will ever hear bandied around about his colleagues like Godard.

It seems utterly perverse that Truffaut’s work has, at least temporarily, fallen out of circulation. It is far more accessible than that of most of his contemporaries in the New Wave. The BFI retrospective is therefore very timely. Audiences will discover that, all those cutesy cat and baby scenes notwithstanding, Truffaut’s best films, from The 400 Blows (1959) and Jules et Jim (1962) to Shoot the Pianist (1960) and Day for Night (1973), are every bit as fresh now as when they were first released.

The BFI celebrates the work of François Truffaut from 1 January to 28 February at BFI Southbank, on BFI Player and at cinemas UK-wide

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks