The 10 best European films: From Jean-Luc Godard’s Breathless to Ingmar Bergman’s Wild Strawberries

As Britain looks inward, Geoffrey Macnab picks some of the best work from continental filmmakers

It’s difficult to believe how exotic and alluring European cinema once seemed to British cinemagoers. Maybe that’s how European movies will appear again now we have left the EU. As we look inward, the work of continental filmmakers will provide us with reassuring, visa-free access to cultures that will suddenly seem very far away.

Those of a nostalgic disposition hark back to a time when European cinema was so often braver, stranger and sexier than its British equivalent. The great auteurs of the postwar years – Agnes Varda (who died last year), François Truffaut, Jean-Luc Godard, Ingmar Bergman and Rainer Werner Fassbinder among them – changed the way that the British thought not only about European film but about continental Europe itself.

Stars such as Anita Ekberg, Monica Vitti, Brigitte Bardot, Catherine Deneuve, Harriet Andersson and Hanna Schygulla seemed wildly glamorous to the British public. Marcello Mastroianni had an air of world-weary sophistication and Max von Sydow a gravitas that few of the UK actors could match. Alain Delon and Jean-Paul Belmondo were effortlessly cool.

Even comparatively recently, audiences would queue around the block to see Gerard Depardieu in Cyrano de Bergerac or Audrey Tautou enrapturing the locals in Montmatre in Amélie or to steep themselves in the secret world of the Stasi in The Lives of Others.

Maybe, in a post-Brexit Britain, we will pay more attention to the great European directors of today, filmmakers like Claire Denis, Pedro Almodovar, Aki Kaurismaki, Lars von Trier and the Dardennes. Their work has been increasingly hard to find in British cinemas in recent years but could now be cherished as a link to the Europe to which we no longer belong.

People on Sunday (1930)

Dir: Robert Siodmak, Edgar G Ulmer

What did young German people get up to at the weekend in Weimar Berlin? If this silent film is the measure, they ate, drank, went to the park, mucked around and had sex in the woods. People on Sunday is as fresh today as when it was first shown. It was made by some of the most talented figures in German cinema history, all at the very start of their careers and all about to be forced abroad by Hitler. Billy Wilder was the screenwriter, while Fred Zinnemann was the cinematographer. Called a “film without actors”, it is utterly fascinating as a slice of social history but also has a wild mischief and youthful energy.

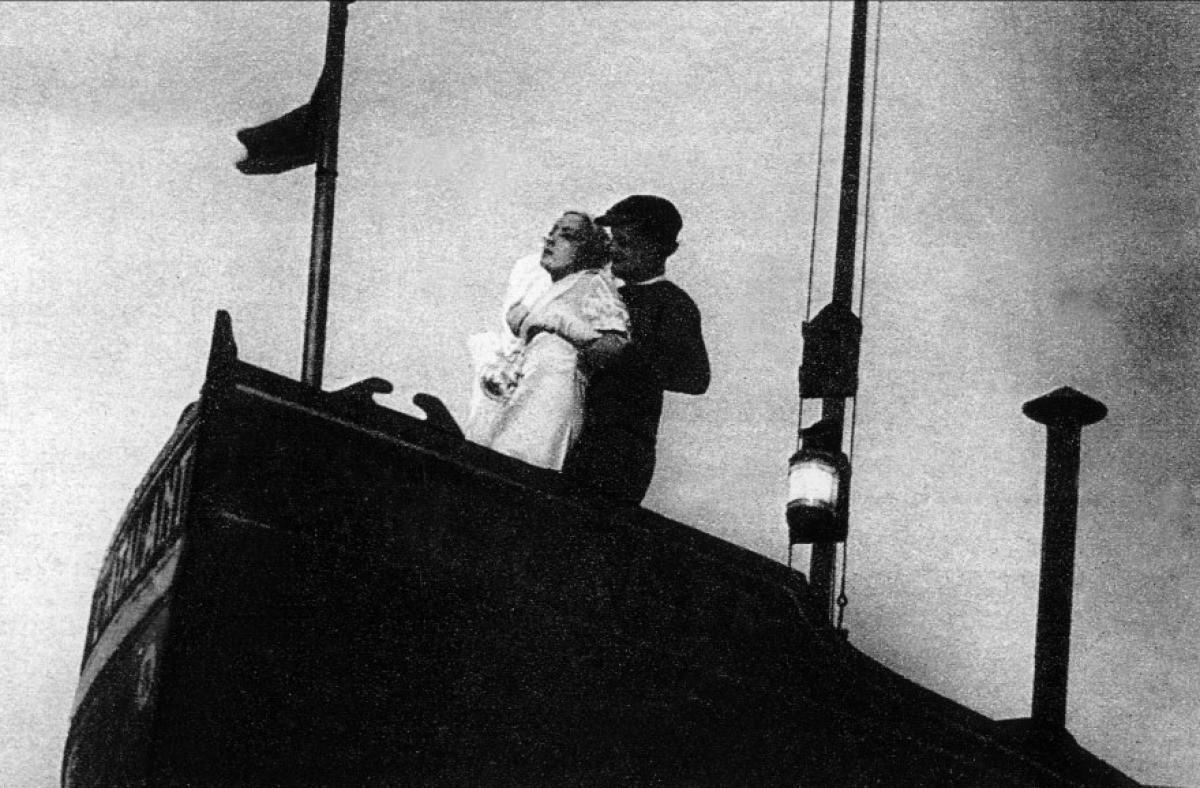

L’Atalante (1934)

Dir: Jean Vigo

“Vigo is cinema incarnate in one man,” the legendary French film curator Henri Langlois rhapsodised about director Jean Vigo, who died of TB aged only 29 in 1934. That was the year Vigo completed his masterpiece, L’Atalante, a film not only revered by generations of critics but still considered a viable dating movie today. It tells the story of a barge journey across France. Two newlyweds, Captain Jean (Jean Dasté) and his sweetheart Juliette (Dita Parlo), set off together, madly in love, accompanied on their voyage by the ship’s barnacled mate Pere Jules (played by the great French character actor, Michel Simon). Jealousy, discomfort and homesickness threaten to fray the relationship. The film is both a paean to rural France and an astonishingly delicate and lyrical love story.

La Règle du Jeu/The Rules of the Game (1939)

Dir: Jean Renoir

We probably wouldn’t have had Downton Abbey without it. Jean Renoir’s film was a direct influence on Robert Altman’s Gosford Park, scripted by Julian Fellowes, who would later create Downton. The British may like to think that they originated the country house drama but Renoir does a superb job here, both upstairs and downstairs. This is a comedy of manners but one featuring conspiracy, betrayal and murder. On the evidence here, the French upper classes were just as corrupt and hypocritical as their British equivalents. “I wanted to depict a society dancing on a volcano,” the director later observed of the film, made just before the start of the Second World War.

Viaggio in Italia/Voyage to Italy (1954)

Dir: Roberto Rossellini

The wonderfully supercilious George Sanders shows his familiar mellowness of sneer as the husband being very beastly to his wife (Ingrid Bergman) in Rossellini’s dark romantic drama. The director was one of the pioneers of Neorealist cinema but this was a film in a very different register to his earlier epics Rome, Open City and Paisa. It’s a caustic, uncomfortably intimate psychodrama about a couple on holiday in Naples whose marriage is falling apart. They can hardly bear to look at each other. Rossellini throws in references to antiquity – and in particular to the disaster at Pompeii – to show the couple’s relationship in a very different light. The film has one of the strangest, most surprising and moving endings in all of cinema.

Wild Strawberries (1957)

Dir: Ingmar Bergman

British (and international) perspectives on Sweden are very strongly influenced by the films of Ingmar Bergman. Summer with Monika (1953), with Harriet Andersson as “mucky Monika”, dealt with sexuality in a far freer way than any British films from the period. The Seventh Seal (1957) fixed the image of the gloomy, introspective Scandinavian playing chess with Death on the beach. Bergman’s Wild Strawberries, about a vain old professor (Victor Sjostrom), about to receive a great honour, looking back on his life, is an achingly beautiful film. It opens with one of cinema’s great dream sequences. In the course of the movie, the Scrooge-like professor revisits his past, comes to terms with his old demons and very movingly begins to mellow.

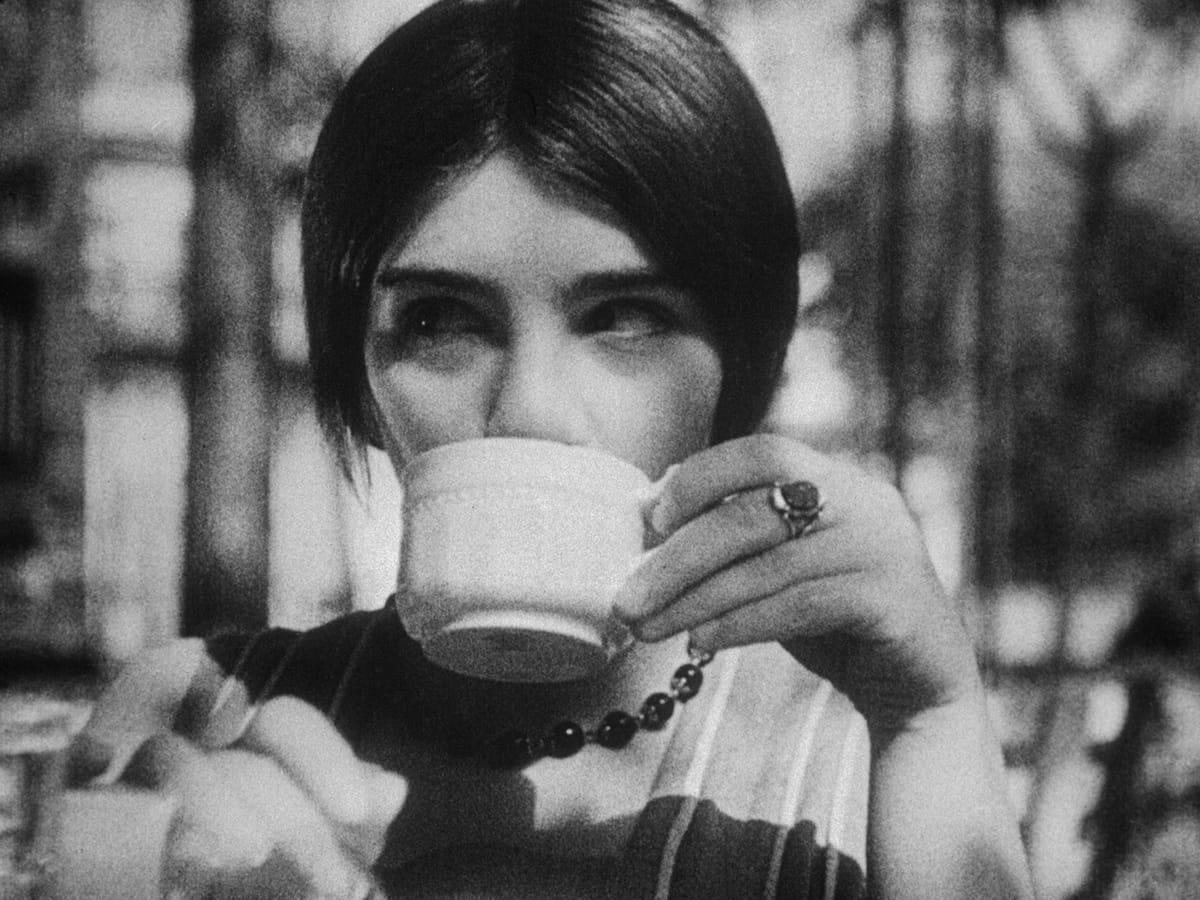

A Bout de Souffle/Breathless (1960)

Dir: Jean-Luc Godard

Godard’s famous formulation that all you need to make a movie is ‘a girl and a gun’ has a whiff of sexism about it. Breathless, though, is an example of a European New Wave film that blew everybody away. You could ignore the gossamer-thin crime thriller plot altogether and just concentrate on the formal boldness (all those jump cuts) and the interplay between the two stars. Movie couples didn’t come any more charismatic than the close-cropped Jean Seberg in her “New York Herald Tribune” T-shirt and Jean-Paul Belmondo as the petty gangster, coming on like a Gallic Humphrey Bogart – but a craggier, better looking one who managed to make the simple act of smoking a cigarette into a supreme poetic endeavour.

The Discreet Charm of the Bourgeoisie (1972)

Dir: Luis Buñuel

Spanish director Luis Buñuel’s Oscar winner about a group of well-heeled characters trying, and failing, to have dinner offered everything bourgeois British audiences wanted in a European arthouse movie. It was risque (the dinner hosts upstairs attempting to have sex while their dinner guests wait below), funny, morbid and very surprising. Imagine an X-rated version of The Good Life or Abigail’s Party and you’ll come close to its essence. In its own more restrained way, the film was also as subversive as Un Chien Andalou, Buñuel’s earlier surrealist masterpiece (co-directed with Salvador Dali). As American director Alan Rudolph noted approvingly, “watching this for the first time took every muscle in my appreciation mechanism. The satire is sharp, the tone startling, the humour cathartic.”

Veronika Voss (1982)

Dir: Rainer Werner Fassbinder

Rainer Werner Fassbinder was the arch provocateur of European arthouse cinema in an era of huge generational friction in German society. He died young, aged 37, in 1982, but racked up an astonishing number of films. This was his penultimate feature, an elegiac and twisted Sunset Boulevard-like love story about the romance between a hardbitten sports reporter and an ageing, drug-addled movie star, disgraced because of her links to the Nazi regime. The film has grim moments involving drug addiction and the Holocaust. It is also gorgeously shot in black and white, boasts a beguiling score by Peer Raben, and is full of unexpected moments of lyricism and tenderness. As director Mark Cousins put it, “Rainer Werner Fassbinder’s women are versions of himself, his languor and despair. Wow.”

The Three Colours Trilogy (1993-1994)

Dir: Krzysztof Kieslowski

When the Iron Curtain came down, many eastern European filmmakers were left at a total loss. They had spent their careers making veiled critiques of the Soviet Union and didn’t know what stories to tell next. Krzysztof Kieslowski was one Polish director who adjusted comfortably to changing times. His Three Colours trilogy, a series of features made in quick succession, looked at liberty, equality and fraternity in strictly personal and metaphysical terms. The three features were closely focused character studies. Some critics sneered that the trilogy, with its beautiful protagonists (Juliette Binoche, Julie Delpy, Irene Jacob), looked like shampoo commercials. The glossy production values notwithstanding, these commercially successful European arthouse films ventured into spiritual, philosophical realms that few British films would go near.

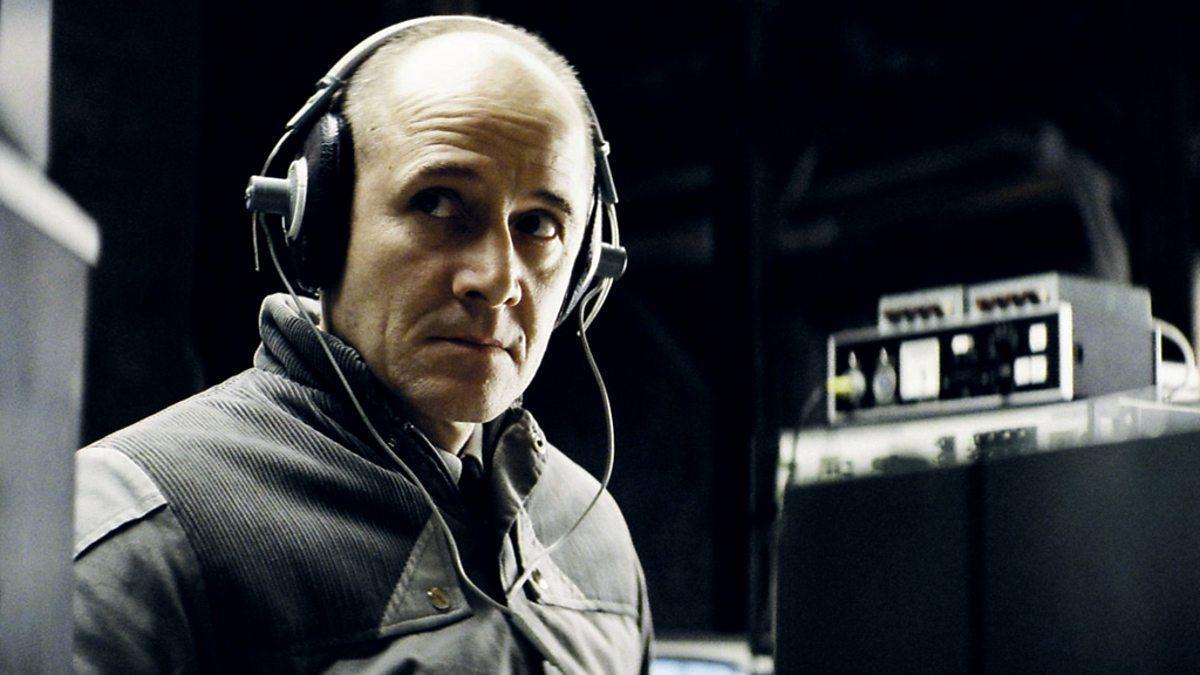

The Lives of Others (2006)

Dir: Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck

Nobody thought much of The Lives of Others at first. The Cannes Festival turned it down for competition. So did Berlin. Nonetheless, when it finally reached British cinemas in 2007, audiences were fascinated by debut director Florian Henckel von Donnersmarck’s depiction of an East German society in which everybody snooped on everybody else. Donnersmarck somehow gave a story about the Stasi spying on a playwright with suspect views a huge emotional kick. Anyone expecting a John Le Carré-style Cold War drama was wrong-footed by a film in which even the clammy, voyeuristic state spy (Ulrich Muhe) ends up behaving with an unexpected nobility and selflessness.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks