‘Part of the culture’: How the Carry On films became the most lucrative comedy franchise in the history of British cinema

As the last film in the franchise, ‘Carry on Columbus’, turns 30, Geoffrey Macnab looks back on what made the innuendo-filled, bawdy movies so popular – and whether they would stand up today

It’s 530 years since Christopher Columbus “discovered” America in 1492 – and 30 years since an almost equally significant event, the release of the final Carry On film, Carry on Columbus (1992).

“There are some chuckles along the way,” acknowledged the film trade magazine Variety, whose critic at the time applauded the film’s familiar use of bawdy humour and double entendres. This was the 30th entry in a franchise that stretched back to 1958. Shot quickly and cheaply, it starred the strapping Jim Dale as Columbus and a gently subversive June Whitfield as Queen Isabella of Castile. No classic (it was later voted “the worst British film ever made”) it nonetheless allegedly turned a profit.

“They were all under budget, and they all made money in great sums,” Peter Rogers, the redoubtable producer behind the Carry On series, once told film historian Brian McFarlane.

The series is still held in immensely strong affection by the British public. Several of the Carry Ons are now available on Britbox in what the platform describes as “remastered and re-loved” editions. They have been painstakingly restored as if they are recovered treasures from an ancient, lost civilisation. “Contains sexual innuendo,” the billings tell potential viewers, although it’s not clear whether this is a warning or a recommendation.

Oscar-winning producer Jeremy Thomas is the nephew of Gerald Thomas, who directed the Carry On films. As a boy, Jeremy, born in 1949, was on the set of the very first film in the series, Carry on Sergeant (1958), and he also visited many of the later productions during his summer holidays. He has gone on himself to produce art-house epics like Bernardo Bertolucci’s The Last Emperor and David Cronenberg’s Crash, but his affection for the “beautifully coarse” Carry Ons remains undimmed.

“The good ones are very, very good. They are part of English heritage as much as Charlie Chaplin or Ken Loach or Powell and Pressburger,” Thomas tells The Independent. “I am not saying the films have the same value artistically but, vis a vis heritage, it [the Carry On series] is England. It is part of the culture.” He believes that the best entries in the series contained social and political insights as well as lots of lewd jokes.

For the three decades in which they made the Carry On films, producer and director Peter Rogers and Gerald Thomas were British cinema’s answers to alchemists, turning very base materials into box-office gold. The later films in the series, after some of the mainstays like stars Sid James and Hattie Jacques had either moved on or died, lost some of their glow – but they still made money. That is why it is so surprising that no further Carry Ons have been made since 1992.

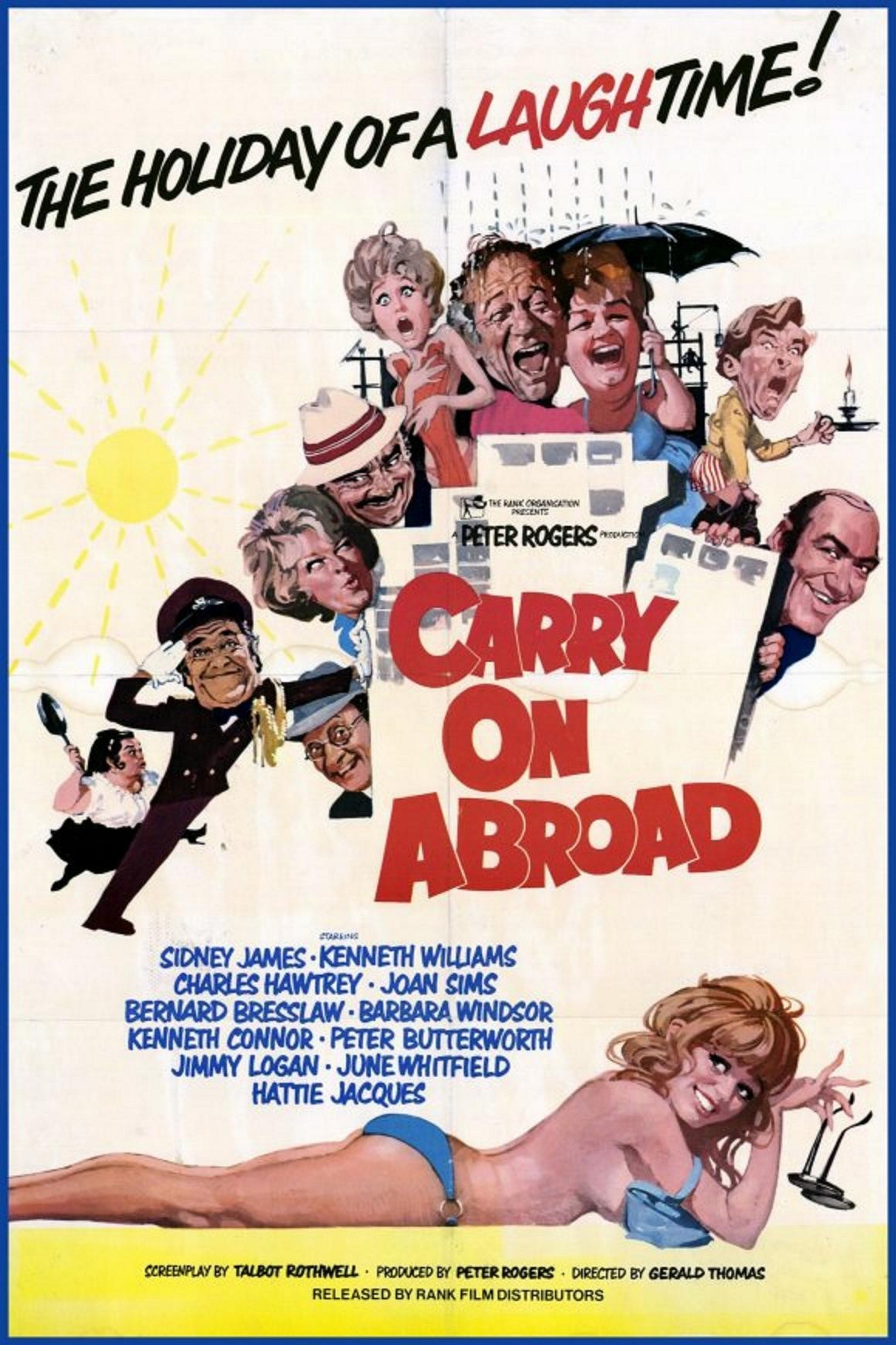

It would be a mistake to think that the British have grown out of the saucy seaside postcard vulgarity that the Carry On films celebrate. In some areas, it seems, neither our humour nor our prejudices have changed significantly over the last 30 years. Brexit suggests we are just as suspicious about continental Europe as we were when Kenneth Williams’s tour guide Stuart Farquhar (“stupid what?”) led the bus party on their ill-fated holiday to a half-completed hotel in a sweltering Mediterranean resort in Carry on Abroad (1972).

After the rise of the #MeToo Movement, you might think that contemporary viewers would find the sexual politics of Carry On to be well beyond the pale. Whether it’s Sid James leering lasciviously at Barbara Windsor’s breasts or screenwriter Talbot Rothwell churning out yet more innuendo-laden one-liners about woodcutters with big choppers, attitudes in the series toward love, courtship and gender always tended to be on the troglodyte side. Nonetheless, revisionist critics argue that the Carry On films are, actually, “defiantly feminist”.

This is certainly the perspective of Caroline Frost, author of the new book Carry On Regardless. As Frost tells The Independent, she divides the 30 films (not including the compilation movie That’s Carry On!) into three periods. The first films in the series, scripted by Norman Hudis, “prick” the institutions of the period: the army, the police force, schools and the NHS. The main roles tend to be played by men because they are set in institutions dominated by males. Even in these early films, though, female actors like Hattie Jacques and Joan Sims have significant roles.

Then came what Frost calls “the golden age” of Carry On, with period romps and spoofs like Carry on Cleo, Carry on Screaming, Carry on Spying and Carry on Up the Khyber. “I would argue that the producers and writers gave the female characters a lot more to do than did the original films that they were themselves parodying.”

The author’s argument about the feminist credentials of the series doesn’t entirely stand up to scrutiny. It’s hard, for example, to find a progressive subtext in the famous scene in Carry on Camping (1969) in which Barbara Windsor’s bra suddenly flies off, landing smack in Kenneth Williams’s face, after she has been doing some excessively vigorous early morning aerobics. Frost, though, argues that by this time (the beginning of the permissive era) “all bets were off. Society itself was changing. Women were no longer staying at home, cooking their husbands’ dinners. They had liberation on their minds both in the workplace and in the personal space – and I think the films reflected that.”

As for the jingoism and the fear of foreigners found in films like Carry on Abroad, Jeremy Thomas argues that these jokes are more at the expense of the nervous, insular, repressed British themselves than their more sophisticated European cousins. His uncle Gerald, he proudly points out, had a house in France. “He loved abroad like everybody does.”

Far more craft went into the comedies than their detractors acknowledge. They may have had low budgets but top technicians often worked on them. For example, Carmen Dillon, a legendary art director and production designer whose best-known credits include Laurence Olivier’s Hamlet and Joseph Losey’s The Go-Between, also worked on Carry on Constable and Carry on Cruising.

Gerald Thomas and Peter Rogers were very skilled at commandeering leftovers from other, bigger movies. They used some of the sets from Chitty Chitty Bang Bang on Carry on Up the Khyber and famously borrowed costumes and equipment from the hugely expensive Elizabeth Taylor vehicle, Cleopatra, for their spoof, Carry on Cleo.

Carry Ons have the habit of making you smirk against your better judgement. There is something engagingly feeble about some of the jokes. Watch the opening credits for Carry on Abroad and you see the actors and technicians listed in traditional fashion. However, the film’s technical adviser, a certain Sun Tan Lo Tion, isn’t a name you’ll find working in any other British productions of the time.

The parochialism is also a selling point. Bond movies shoot in exotic locations. The Carry On pictures were made in such far-flung places as the town hall in Slough, the car park at Pinewood Studios or the Odeon Cinema in Uxbridge. If the producers couldn’t afford to shoot in the actual Sahara desert, they could always use Camber Sands in Sussex instead, obviously the next best thing even if shooting was interrupted by too much snow at the seaside.

Jeremy Thomas remembers going into cinemas full of spectators “riotously laughing” at the latest Carry On. Every few minutes, there would be a new pun or gag and a fresh explosion of mirth. That mood was replicated on the sets that he regularly visited. “They [the actors and technicians] were having incredible fun,” he says. “It was incredibly joyous, happy filmmaking. That’s my vision of it. I saw it with my eyes as a young person. It was a riotous endeavour that went on for 30 years.”

So what do the Carry On films mean today? Caroline Frost acknowledges that younger viewers may find them utterly baffling. “The Carry On films were a lot bawdier and would be seen as quite offensive… they made fun of everybody including women and including people who quite rightly would not be the targets of offensive jokes and humour now. They did stuff you can’t get away with any more.”

For old-timers, though, the pleasure never fades. One of the quirks of the Carry Ons is that you can watch them again and again. Jeremy Thomas says that if he is channel surfing and stumbles on one of them, he’ll always be “happy to dip in” even if he has already seen the film “50 times before”. He’ll still also laugh in exactly the same places.

“Infamy! Infamy! They’ve all got it in for me!” the toga-clad Kenneth Williams, playing Julius Caesar, famously shrieked as the assassins came after him during Carry on Cleo. He could just as well have been talking about the high-minded critics who skewered each new movie in such cruel and patronising fashion.

There is a sense that the films remain under-appreciated partly because they were so successful. Comedies are notoriously hard to pull off. In his own distinguished career, Jeremy Thomas has never even attempted one. His uncle Gerald, though, turned them out by the dozen.

“[The success of the Carry Ons] was a lot harder than they made it look. That has been proved by the fact that nobody has been able to repeat it,” Frost says of what remains easily the longest-running and most lucrative comedy franchise in the entire history of British cinema.

Several Carry On films are available on Britbox. ‘Carry On Regardless: Getting to the Bottom of Britain’s Favourite Comedy Films’ by Caroline Frost is available now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments