Capturing the Moment? It’s more painting by numbers in this so-so Tate show

Painting and photography square off in this new show full of big hitters but with no clear message or purpose

Painting is supposedly undergoing a renaissance, but there’s barely an artist working today who doesn’t employ photography in one form or another. Indeed, in our photo-tweaking, Instagram-posting, image-manipulating times, painting has become, it could be argued, a mere by-product of photography.

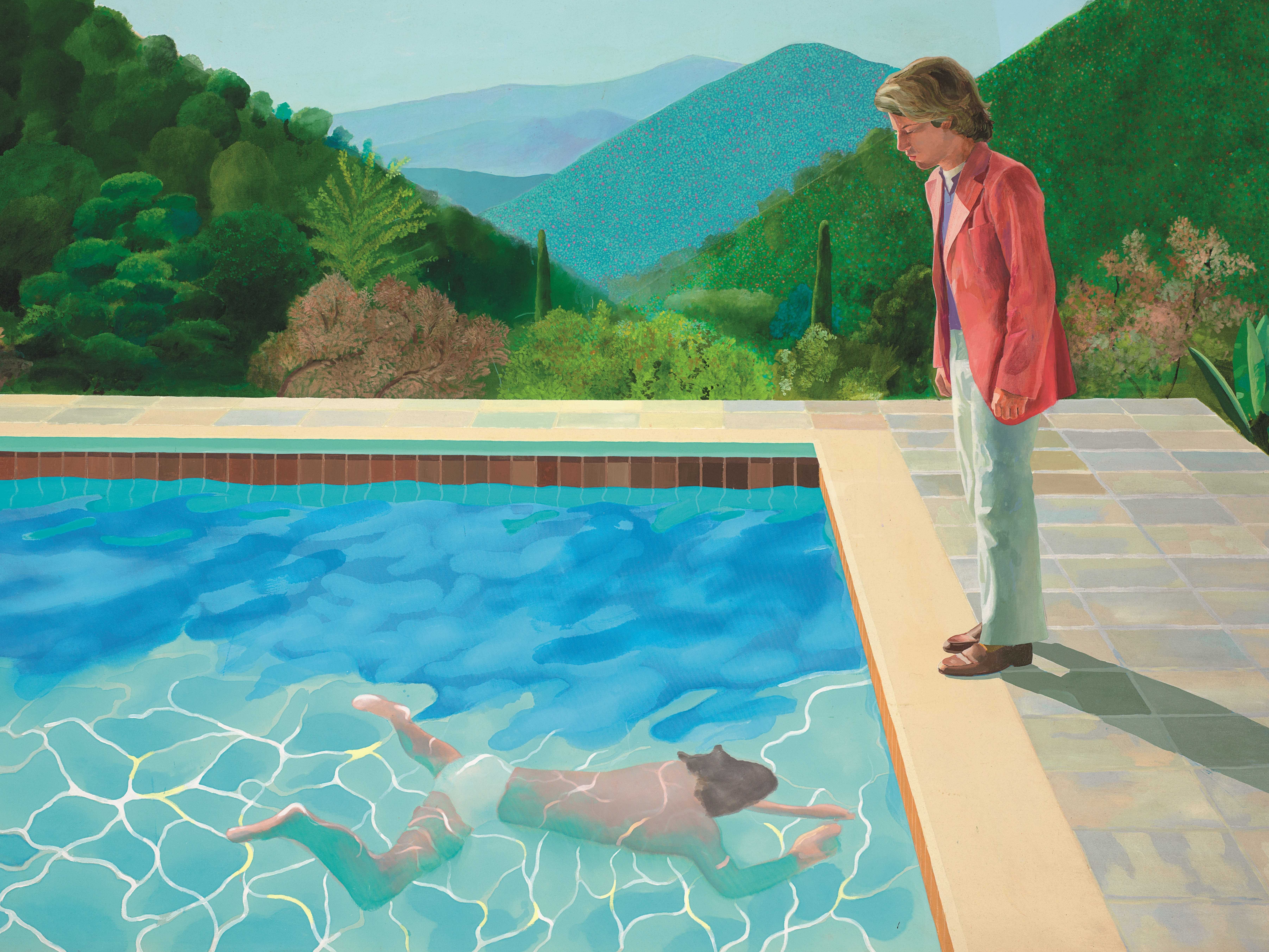

This potentially hugely vexed field provides fertile ground for a major Tate exhibition, exploring the “dynamic relationship between contemporary painting and photography”. Capturing the Moment draws substantially on the collection of the Yageo Foundation, created by the Taiwanese electronics giant, which famously bought David Hockney’s Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) for $89m – then the most expensive painting by a living artist – in 2018. The show puts modern master paintings by the likes of Francis Bacon, Gerhard Richter and Peter Doig into “dialogue” with recent acquisitions by younger artists from the Tate’s own collection.

With the stage set for a really prickly and entertainingly rivalrous encounter between the two mediums, it’s surprising to find ourselves looking at paintings by Lucian Freud – an artist who prided himself on only painting directly from life – as we enter the show. The title of the room, however, gives the thinking behind the display and, indeed, the entire show, away: Painting in the Time of Photography. Since all painting has been somehow touched by an awareness of the possibilities of photography since the mid-19th century advent of the medium, the exhibition seems to regard just about any painting created since 1830 as within its remit. Freud’s poignant The Painter’s Mother IV (1973) is justified on the grounds of its downward-pointing – and arguably photographically inspired – angle over her crumpled features.

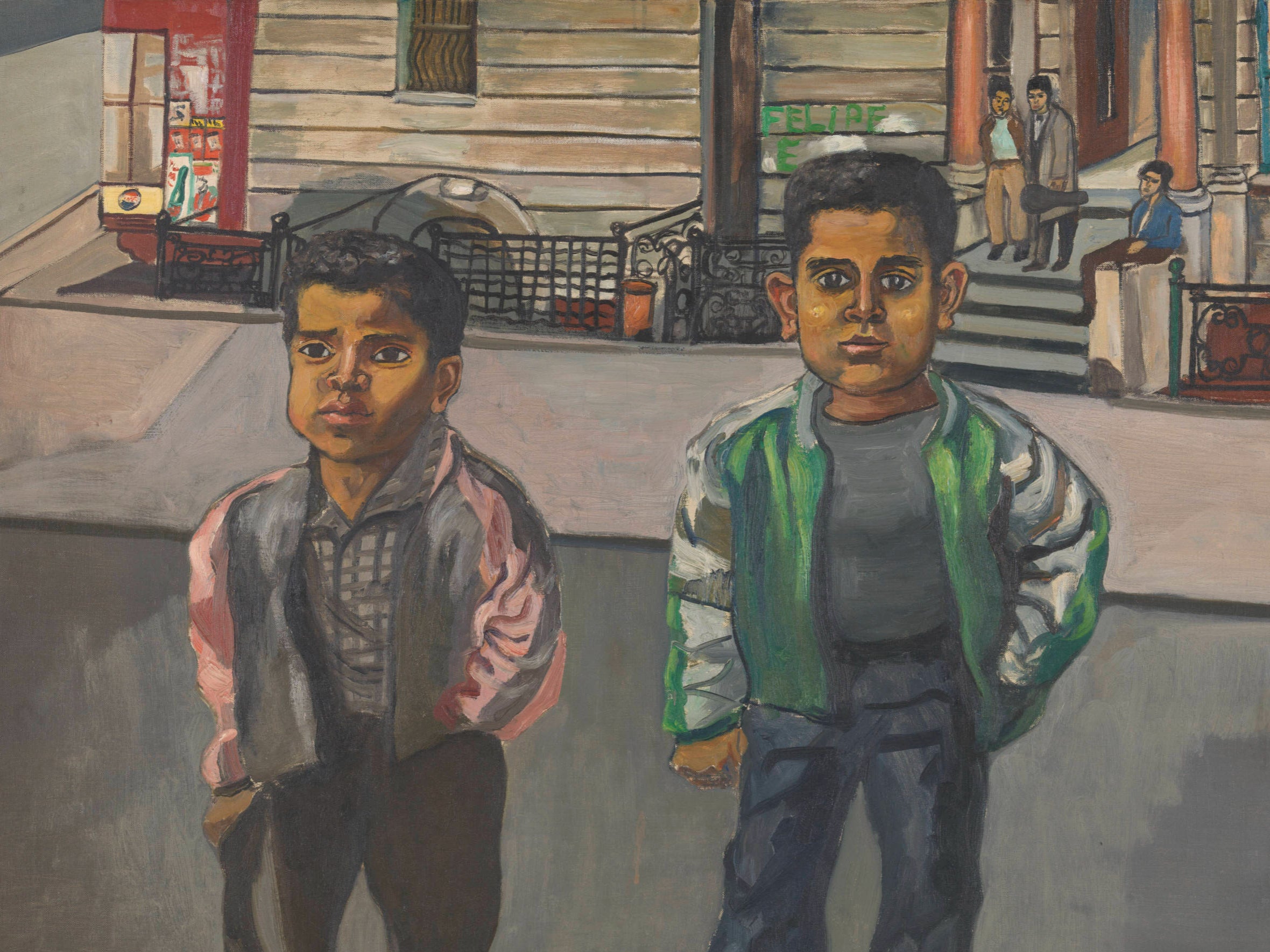

Dorothea Lange’s iconic photograph Migrant Mother, Nipomo, California (1936), showing a drawn and exhausted Depression-era mother cradling her child, is put into conversation with Picasso’s Weeping Woman painted a year later in response to the Spanish civil war, and Alice Neel’s cloyingly faux-naif Dominican Boys on 108th Street (1955). While it would be nice to report that a signature work by one of the greatest painters of the 20th century has far greater truth than a mere photograph, the harrowing veracity of Lange’s image makes the Picasso look facile and kicks the Neel right out of the gallery.

This though is the only directly competitive moment in the entire exhibition. Rather than develop a strong central argument, the show seems content to point out the differences, similarities, angles and echoes between works to frequently inconclusive and sometimes blindingly obvious effect.

A room called Tensions, for example, is manifestly lacking in tension. Francis Bacon is one of painting’s great users and abusers of photography. But Study for a Pope VI, one of a series based on a photograph of Velazquez’s Portrait of Pope Innocent X, isn’t a great example of his ability to “emotionally charge… every brushstroke”, as the wall texts have it.

In the same room, Paula Rego’s War (2003), a melee of sinister rabbit-headed figures based on a snap of a terrified woman carrying a baby during the Iraq war, would make more sense if the photograph were shown alongside. Georg Baselitz’s trademark “upside down” painting Orange Eater II (1981) seems unconnected to photography, but it’s a nice work from the Yageo collection, so, hey, why not include it?

When it comes to photography influenced by painting, the exhibition spends far too much time telling us what we already know. Seen on a wall-filling light box in a darkened room, Jeff Wall’s A Sudden Gust of Wind (1993) has a truly cinematic impact. Four wind-blown figures run after flyaway scraps of paper in an image derived from an 1831 woodblock print by the Japanese artist Katsushika Hokusai. Yet the fact that the image, with its photoshopped figures and paper undercuts our perceptions of photography as a “faithful” capturing of a single moment, will come as a revelation to no one. While many gallery-goers still struggle with some of the basic premises of modern art, the infinite malleability of photography is something everybody these days just gets. For once the public understanding feels ahead of the curators’ rhetoric.

German painter Gerhard Richter’s blurry photorealist paintings are generally considered some of the most intelligent explorations of the boundaries of painting and photography, though their clever-clever appeal has always passed me by. Is that actually two candles in Two Candles (1982) or one candle and its reflection in a mirror? Do we care? He’s quoted on the wall as saying “the most banal amateur photograph is more interesting than the most beautiful painting by Cezanne”. Fair point, but I’d have been happier if he’d made that, “the most beautiful painting by Gerhard Richter”.

But that Hockney painting, Portrait of an Artist (Pool with Two Figures) (1972), used as the show’s poster image, makes a far stronger impact than I expected. Showing Hockney’s long-time boyfriend Peter Schlesinger, from whom he had recently separated, looking pensively down at another young man in a Californian swimming pool, the large-scale painting might have felt a touch sentimental, even cheesy. Certainly, the contrast of realistically rendered figure and abstracted water feels Hockneyesque to an almost cliched degree. Yet there’s an authentically tragic note in the merging of past and present in a composition Hockney assembled from a collection of random personal snaps. I’d almost forgotten he could do paintings this good.

Around this we’re given an interesting, but oddly arbitrary selection of works, including a wall full of grade-A Pop Art – though some of the best pieces are from Tate’s own collection. Peter Doig is so much the great photographically-inspired painter of our times that including his Canoe Lake (1997) feels almost gratuitous. American painter John Currin, who I generally can’t stand, provides the quirkily sinister Thanksgiving (2003), in which three versions of his long-necked wife cook the turkey.

While there’s little outright copying of photographs – and oddly almost no photorealism – in the show, there’s the sense that art today is about synthesising and curating existing stuff, from iPhone images and works of art to just about everything you can imagine from everyday life. The idea of creating original form, whether through imagination or observation, feels long gone. The most notable exceptions to this come, hearteningly, in the final room with Laura Owens’s near-abstract post-internet paintings and Christina Quarles’s wacky digitally-derived figures that look at times as though they’re stretched out of chewing gum.

These though are a mere aside in a show that takes us on a pleasant enough amble through a lot of mostly excellent recent painting and photography, without providing a strong argument – or indeed any real argument – for why we’re there. It feels as though a large body of works were made available from one of the world’s major collections, and a rationale hastily developed around them. In these straitened, post-Covid times, that must present an appealingly cost-effective way of mounting an exhibition; though looking at the ticket prices, the savings aren’t being passed on to the viewer. It doesn’t bode well for the future.

Tate Modern, until 28 January 2024

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks