The Cannes Film Festival’s geriatric 2023 line-up risks a slide into irrelevance

The Cannes director Thierry Fremaux has filled this year’s event with movies from silver-haired figures, but, says Geoffrey Macnab, it risks sapping the energy from the world’s biggest and most prestigious festival

When did filmmakers start getting so old? Look through the main programme of this month’s Cannes Film Festival and you will find new work from all over the world by directors so venerable that they make US politicians Joe Biden and Donald Trump look youthful by comparison.

Cinema used to be regarded as a young person’s medium, but Cannes director Thierry Fremaux has filled this year’s event with movies from silver-haired figures who wouldn’t look out of place playing shuffleboard in a remake of Ron Howard’s OAP comedy, Cocoon. (1985). In paying such extravagant homage to these older directors, he risks sapping the energy from the world’s biggest and most prestigious festival.

The revered Martin Scorsese, who is back at the festival with Killers of the Flower Moon, has just hit 80. The German director Wim Wenders, who has two new films in the festival, is 77. He was one of the faces of New German Cinema, but that was back in the 1970s. The UK’s Ken Loach, who is presenting his new film The Old Oak, the title seems strangely apt, is 87 next month.

The esteemed Italian auteur Marco Bellocchio, returning to the Riviera with his 25th feature film, Kidnapped, is 83. The controversial French director Catherine Breillat’s new feature, Last Summer, is about a sexual relationship between a middle-aged woman and her teenage stepson – and Breillat herself is a strapping 74-year-old. Maverick Japanese director Takeshi Kitano, the godfather of Japanese gangster movies and who is unveiling his new period drama Kubi, is 76. The Spaniard Victor Erice is making his comeback with Close Your Eyes at the age of 82.

Accompanying these septuagenarians and octogenarians to the festival is a phalanx of filmmakers in their sixties, among them Todd Haynes, 62, whose new film May December stars Natalie Portman and Julianne Moore.

This year’s festival, then, has the feel of an arthouse cinema equivalent to a nostalgia-fuelled comeback tour by an Eighties pop band. It is showcasing work by familiar names who made great movies in the past.

The divisive American Woody Allen, 87, won’t be shuffling up the red carpet at Cannes. Fremaux drew the line at screening his new French-language comedy Coup de Chance. “If his film is shown at Cannes, the controversy would take over against his film, against the other films,” the Cannes boss explained to trade publication IndieWire.

Roman Polanski, 89, another director with an equally problematic reputation, also missed the cut with his latest feature, The Palace, a film whose eclectic cast includes the unlikely pairing of John Cleese and Mickey Rourke. Fremaux said it wasn’t a candidate for selection, which suggests it wasn’t ready in time, but Cannes is already packed with movies from other old devils of world cinema.

On one hand, the presence of all these gnarled veterans is testament to the continuing excellence of their work. When the Cannes programmers identify filmmakers they admire, they tend to keep on inviting them back as long as their movies are up to par. One regular visitor, the late Portuguese director Manoel de Oliveira, was 101 years old when he presented his 2010 feature, The Strange Case of Angelica, in Cannes. Eight years after his death, in 2015, he has a film screening this year too – his 1993 feature Abraham Valley is being shown in honour of its 30th anniversary.

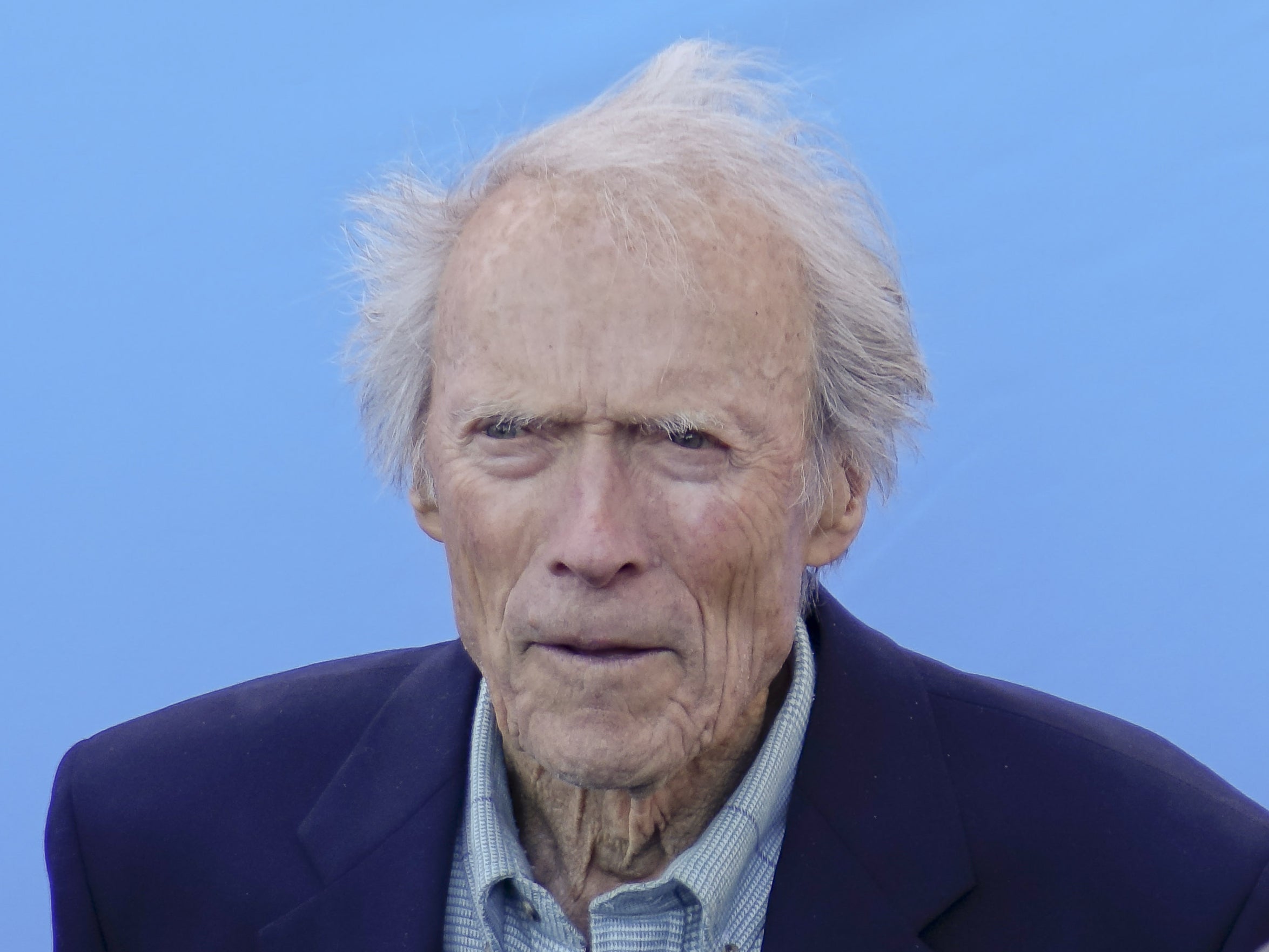

Clint Eastwood, now in his nineties, is another favourite of the Cannes programmers and must be a strong bet for selection next year, once he has completed his next and possibly final feature, Juror No 2. Ridley Scott, 85, was tipped for a Cannes berth for his new Napoleon biopic starring Joaquin Phoenix as Bonaparte. It turns out the film won’t be in the selection – unless it is added late on – but, even without it, the average age of directors selected by the festival is creeping inexorably upward.

The fact that directors like Scott, Scorsese, Bellocchio, Allen and Eastwood can get new projects into cinemas and on to streaming platforms points to a complete sea change in the way movies are now financed. It used to be almost impossible for filmmakers of their age to keep on working. No one would insure them. Making films is stressful and physically demanding work. Producers fretted that they simply wouldn’t have the energy to complete the job effectively. They also questioned whether these directors would be capable of attracting the younger cinemagoing audience that the box office depends on.

Cinema history is littered with stories of once-feted figures spat out by the system as they grew older. Orson Welles made his masterpiece Citizen Kane (1941) when he was still in his mid-twenties – and it was downhill from there as far as his status in Hollywood was concerned. By the end of his career, studios and financiers were reluctant to go near him.

There are many poignant accounts of Billy Wilder late in his life turning up at his office every day to work on projects that would never come to fruition. “You don’t know you have retired until after it happens,” he told Wilder biographer Charlotte Chandler about the end of his career when he couldn’t get a project off the ground. The longer he stuck around, the more he felt his reputation was diminishing. “It’s like a New York Times obituary. If you outlive your fame, you lose paragraphs,” he lamented.

In the rare cases that older movie directors were allowed back on to movie sets, someone would always have to be there to hold their hands. When Robert Altman was in his late seventies and making costume drama Gosford Park in London, he had younger director, Stephen Frears, on call at all times, ready to step in if his health should fail. The same applied for the Italian filmmaker Michelangelo Antonioni when he made Beyond the Clouds (1995). Antonioni, then in his eighties, had suffered a stroke a few years before which affected his ability to speak. However, after Wenders agreed to work alongside him, the financiers allowed the picture to go ahead.

Now, it is youth that isn’t trusted. Financiers are far more comfortable with seasoned talent they know than with newcomers. This applies to the actors as well as the directors. Tom Cruise, now 60, was the toast of last year’s Cannes Festival with Top Gun: Maverick and is still performing death-defying motorbike stunts for his new Mission Impossible films.

Many of the stars expected to excite the paparazzi in Cannes are also getting long in the tooth. Johnny Depp, who plays Louis XV in the festival’s opening film Jeanne du Barry, turns 60 next month. Robert De Niro, who stars in Scorsese’s film, will be 80 in August. Moore, the star of Haynes’s flick, is 62.

Quentin Tarantino will be in Cannes this month as a special guest of the Directors’ Fortnight. This is the sidebar set up in the late 1960s to showcase new filmmakers making movies too radical and idiosyncratic for the main competition. Nobody can question Tarantino’s credentials as one of US indie cinema’s most prominent mavericks but he too is in his sixties.

It is telling that most of the well-travelled directors whose work the festival is so keen to foreground this year came of age as artists in the 1960s and 1970s, an era of radicalism and new movements in cinema. They defined themselves against an older generation. They tended to be progressive politically, innovative formally and rebellious in spirit. Now, they are old themselves – but still trying to make the same irreverent, polemical, taboo-breaking movies that they did in their prime.

If they were at the start of their careers today, trying to break through, how would they react to the refusal of the old guard to step aside?

“French cinema is dying from its false legends,” François Truffaut (1932-1984) famously proclaimed just before the 1957 Cannes festival. At the time, Truffaut was an outspoken young journalist dreaming of making his own movies but being held back by a system that, as his biographers Antoine De Baecque and Serge Toubiana noted, was “fossilised” and “flaunted a haughtiness for novelty and youth”. Truffaut railed against the “cinema de papa” and the many literary adaptations that older French filmmakers were then churning out – whom he called “civil servants of the camera” rather than “true artists”.

He wrote witheringly about the “progressive degeneration” of Cannes. The festival organisers were so stung by his criticisms that they refused him accreditation. It was obvious, though, that the young firebrand, still in his early twenties, was simply trying to shunt some of the old-timers aside, to clear some much-needed space for younger filmmakers.

Maybe Cannes needs an equivalent to a Truffaut to shake it up today. It’s in clear and present danger of turning into an old boys’ club.

Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon may be excellent, but it won’t generate anything like the same excitement created by the director’s Taxi Driver in 1976, when the festival jury, led by playwright Tennessee Williams – who abhorred its violence –awarded it the Palme D’Or. Cannes audiences booed the movie but that only added to its impact. It had a delinquent energy, which reflected the youth of its creative team.

Loach’s film The Old Oak, about the last pub standing in a once thriving mining community, is bound to be full of searing observations about race, class and inequality in the post-industrial UK. Will it have the impact of his 1966 TV film, Cathy Come Home, which provoked questions in parliament and started a nationwide debate about homelessness? Probably not… as the director himself recently told The Hollywood Reporter about the challenges of making a feature film when you’re knocking on 90: “Your facilities do decline. Your short-term memory goes and my eyesight is pretty rubbish now, so it’s quite tricky…”

You can’t help but admire Loach and the other old-timers for staying in the game so long, but if Cannes continues to favour the ancient over the new, its relevance will soon fade.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments