Books of the month: From Rachel Cusk’s Second Place to Jhumpa Lahiri’s Whereabouts

Martin Chilton reviews six of May’s biggest releases for our monthly column

There’s a strange synchronicity to May’s books. The protagonist of Rachel Cusk’s superb new novel Second Place is warned that “you can’t expect to keep a snake as a pet”, in reference to the disaster that unfolds after she invites a cruel, egotistical artist to stay at her remote coastal home. In the acknowledgements, Cusk writes that Second Place owes a debt to Mabel Dodge Luhan’s 1932 memoir about the time DH Lawrence came to stay with her in Taos, New Mexico. “My version – in which the Lawrence figure is a painter, not a writer – is intended as a tribute to her spirit,” writes Cusk.

This struck a resounding bell because I had just finished reading about the poisonous Lawrence and his relationship with Dodge in Frances Wilson’s new biography of the writer, in which Dodge’s husband Tony (the name given to a central character in Second Place) describes Lawrence as “a snake”. Both books are reviewed in full below, along with a non-fiction gem by Dr Emily Mayhew, novels by Jhumpa Lahiri and Rahul Raina, and a fascinating new study of Alfred Hitchcock by Edward White.

I confess I’d never heard of Marguerite Jervis (1886-1964), the author of 149 books, 11 of which were adapted for the cinema, including ones (more coincidence) by Hitchcock. In The Queen of Romance – Marguerite Jervis: A Biography (Honno), Liz Jones pieces together the eventful life of this Burma-born pioneer, including her abusive marriage. Jervis worked in Fleet Street, acted alongside Gloria Swanson, and wrote risqué novels. Many of her books were written under a fake male pen name, Oliver Sandys, and exposed the sexual abuse and addiction problems of chorus girls. Jervis was a trailblazer and merits this publishing spotlight.

Jamaican poet Kei Miller examines discrimination in his non-fiction collection Things I Have Withheld (Canongate). The powerful essays include his own letters to the late American novelist James Baldwin and his reflections on the permanence of racism. He writes movingly about Frank Embree, a boy of 19 who was lynched in front of a crowd of over a thousand onlookers in Fayette, Missouri, in 1899. Miller, referring to the infamous interview Liam Neeson gave to The Independent in which the actor admitted desiring a violent confrontation with “a black bastard”, memorably describes the 19th century crowd of deep south bigots as “a mob of a thousand Liam Neesons”.

Comedian Rosie Wilby offers a lighthearted guide to modern dating and dumping in The Breakup Monologues: The Unexpected Joy of Heartbreak (Green Tree). Among the musings is a droll account of attending a “Sex lab” at the University of Essex. I remember a friend in the early 1980s joking about being “burned off” by a vain boyfriend. Wilby shows that language evolves, noting that the new “therapeutic term” for being dumped is “narcissist discard”.

In Dancing on Ropes: Translators and the Balance of History (Profile Books), Anna Aslanyan looks at the role played by translators in history, and the book is full of oddities and interesting anecdotes. Precise translation is particularly important in wartime. Aslanyan details how the misinterpretation of a Japanese state cable to the Americans in 1945 escalated tensions and ultimately led to the atomic attack on Hiroshima. Sometimes it makes for comedy, too. When Donald Trump referred to “sh*thole countries” in 2018, this was translated in Taiwanese media to “countries where birds don’t lay eggs”.

It’s another good month for history. Gwynne Dyer’s readable, sharp The Shortest History of War (Old Street) does what it says on the tin, while Professor Alice Roberts has written a transporting gem in Ancestors: The Prehistory of Britain in Seven Burials (Simon & Schuster), a truly groundbreaking account of ancient Britain that brings burial sites to life.

Among the month’s most interesting fiction is Natasha Pulley’s The Kingdoms (Bloomsbury), about an alternative universe involving a British slave in the French empire, and Elodie Harper’s The Wolf Den (Apollo), a gripping historical story about a slave in Pompeii’s infamous brothel. I would also recommend Maggie Shipstead’s Great Circle (Doubleday), a riveting tale about a Hollywood starlet who is forced to confront her own troubled life when she is cast to play a daredevil pilot who crash-landed in the Antarctic in the 1950s. There are also plenty of thrills in Andy Weir’s Project Hail Mary (Del Rey), a tale of a lone astronaut’s battle to save the world, by the author of The Martian.

Finally, there are two new imprints starting this month, both launching with debut novels about modern relationships: Kylie Whitehead’s Absorbed (New Ruins) – about a bored female worker who starts taking on her boyfriend’s character – and Emily Itami’s Fault Lines (Phoenix) about a married woman who begins a dangerous affair with a successful restaurateur.

Whereabouts by Jhumpa Lahiri ★★★★★

There is a glorious vignette in Jhumpa Lahiri’s Whereabouts, in which the unnamed middle-aged protagonist sits in a playground in the sun and eats a sandwich. The two-page chapter is written with grace and sensitivity, making art out of an everyday banal action.

Lahiri, who was born in London to Bengali parents and raised in the US before relocating to Rome, wrote Whereabouts in Italian and translated it herself into English. In her pared-down, direct and elegant language, the author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning Interpreter of Maladies explores themes of detachment and loss in 46 brief chapters. One magnificent chapter, “In the Bookstore”, is like a small, haunting short story.

The narrator, a single woman who is an academic, has conflicted feelings about her dead father and elderly mother and admits she cannot escape the shadows cast by her family. “I think a great deal about my parents, and I ask myself, in this sheltered place, why they’re still nipping at my heels,” she says. Lahiri also neatly skewers male pomposity in her description of one of the woman’s former lovers, a born complainer (“that tiresome anxiety, that ongoing lament”) and captures the pain and confusion of dealing with life’s troubles and unforeseen defeats.

There are deeply etched portraits of all the (Italian) whereabouts – the cafes, the parks, the bridges, museums and shops – places that both depress and sustain her. Although there is a palpable sense of estrangement in Whereabouts, there are also life-affirming moments of human tenderness. In my favourite chapter, “In the Hotel”, the protagonist, who is there for a conference she dreads, forms a bond with the scholar next door, even though they barely interact. “Without planning to we wait for each other every morning and every evening, and for three days our tacit bond puts me obscurely at peace with the world,” the woman recalls.

Lahiri has written a gorgeous novel, one full of unsettling contradictions. It left me mulling on aspects of it long after I’d read the final page.

‘Whereabouts’ by Jhumpa Lahiri is published by Bloomsbury on 4 May, £14.99

Second Place by Rachel Cusk ★★★★★

In Second Place, Rachel Cusk’s protagonist (identified only as M) invites an artist (just called L) to the remote marshy coastal landscape. She gradually begins to fear that she has “invited a cuckoo into our nest”. Cusk, the author of the excellent Outline trilogy, slowly and skilfully draws the reader into a compelling psychodrama that is full of surprising, stimulating reflections on creativity, art, culture, power structures, parenthood, and the moral questions that animate our lives. In addition, the descriptions of nature are utterly beguiling.

The novel, written as a first-person recollection to the never-explained character Jeffers, is one to drink in slowly. Some of the scenes are truly striking. One is the account of M’s disturbing street-spat with her former psychoanalyst; another is the moment during a walk when L admits being startled by the sound of gunshots from the fields. M tells him that it is one of the stationary gas-guns the farmers put in their fields to scare the birds off the crops. “Sometimes I liked to imagine, I told him, that it was the sound of wicked men blowing their brains out, one after another,” she says.

The additional cast – M’s daughter Justine, her boyfriend Kurt, L’s young girlfriend Brett (“he’s a vampire on her youth”), and M’s husband Tony – are all rich in character and foibles. Tony aside, the men do not come out well in the novel. They are neglectful and self-absorbed. At one point, L warns her daughter that she will “always be able to find a white man to be obliterated by”.

Some of the most tender moments areelicited byL’s honesty about her own image. She admits she has “grown up disgusted by my physical self”, echoing the insecurity felt so long ago by Dodge (who compared her own shape to a Christmas tree). Cusk allows you to see why she is attracted to such a hardhearted, selfish visitor. He stays in the guest home they call Second Place. “Second place pretty much summed up how I felt about myself and my life – that it had been a near miss, requiring just as much effort as victory but with that victory always and forever somehow denied me,” L admits to Jeffers.

I relished Second Place. It’s a novel of deep insight and scarring honesty – and the ending is flawless.

‘Second Place’ by Rachel Cusk is published by Faber on 6 May, £14.99

The Four Horsemen and the Hope of a New Age by Emily Mayhew ★★★★☆

The Four Horsemen – War, Pestilence, Famine, and Death – have been around since the Book of Revelation and continue to threaten the world. Dr Emily Mayhew, historian-in-residence at the Department of Bioengineering at Imperial College, London, specialises in the study of severe casualty in modern warfare. In her vital, compelling book The Four Horsemen and the Hope of a New Age, Mayhew looks at how humanity is under threat in the 21st century, and she examines the unsung heroes who are battling against modern perils.

In the chapter “War”, Mayhew looks at the extraordinary coalition of humanitarian workers in Mosul, Iraq, who helped save its people from the worst horrors of the liberation battle against ISIS. Her amazing cast includes doctors, scientists, statisticians, engineers, peace negotiators, pharmacists, historians, forensic scientists, vaccinators, and volunteers – all battling under terrible conditions to find answers to life-and-death problems.

Mayhew’s book is rich in explanation and background detail. In “Pestilence”, she records how Ebola got its name from the first recorded outbreak in 1976, near the Ebola River in the Democratic Republic of the Congo. “Scientists who discover new, potentially deadly viruses try to name them after rivers because it’s thought to be unhelpful to name them after villages or towns,” explains Mayhew.

Our own fight for survival against a Covid-19 pandemic is central to the long chapter “Pestilence”. She pays deserved tribute to the health workers – some of whom incurred facial pressure injuries after wearing pressure-sealed filtering face-piece respirators for far longer than recommended. She makes a convincing case about why outbreak analytics will be so important in preparing for “the emergence of the next pathogen epidemic”.

Mayhew also focuses on antibiotic resistance, in what she calls the second age of antibiotics. “Even if only a few bacteria are left behind after a course of antibiotics, under selective pressure the survivors learn to resist, to alter their DNA so they can repair their cell walls and make other proteins so they can reproduce again. The new version of themselves comes with the new learning already incorporated,” is her frightening warning.

Although this is a scary book, it is also one full of hope. “This is the simple and essential truth at the heart of my work: there are more people working in our world for good than any other kind,” Mayhew writes.

‘The Four Horsemen and the Hope of a New Age’ by Emily Mayhew is published by Riverrun on 6 May, £20

How to Kidnap the Rich by Rahul Raina ★★★☆☆

Rahul Raina’s energetic debut novel How to Kidnap the Rich is an exciting blend of crime caper, satire, love story and social commentary, based around the “fast-moving world of educational impersonation”.

Ramesh Kumar escapes his impoverished upbringing in Delhi by tutoring the lazy, mediocre sons of rich Indians, sitting college entrance exams in their place. When he scores the highest mark in India while posing as one of them, it catapults the dimwitted teenager, Rudi Saxena, into a frenzied life of fame, wealth, and excess. Rudi becomes the star of the television show Beat the Brain, while Ramesh remains behind the scenes, controlling the whole masquerade until it comes tumbling down in a chaotic mess of kidnappings, blackmail, mutilation and double-crossing.

Raina, who was born in Delhi, neatly skewers the inequalities of Indian society, racism (education is merely a tool to a “whiter life”), sexism, and celebrity. Despite Rudi’s lack of intelligence and ordinary looks (he is described as having a “no-matches-on-Tinder face”), the youngster becomes a superstar in India. Ramesh controls his life, from his money-making enterprises to his Snapchat, Instagram, YouTube, and Twitter accounts. “I didn’t try to be smooth, a manicured, polished celebrity. I just had to be a normal Indian teenager. I dialled my natural intelligence down about 75 per cent, and there I was,” he says.

A few of the jokes fall flat but, on the whole, the novel is full of sparkling wit. The first half of the novel is the most affecting, detailing motherless Ramesh’s grim upbringing at the hands of his abusive father. “I did not have a good, toothy UNICEF-website smile,” says Ramesh, who has to scramble to get away from a lifetime of working at his father’s tea stall. India’s patriarchy does not come out well in the novel. Fathers don’t communicate with children, husbands don’t listen to wives, and men are generally predatory: when Rudi has to disguise himself in women’s clothing, he is constantly groped.

Along with the fast-paced twists, Raina also satirises the state of modern India: the repercussions of the ongoing rivalry with Pakistan; the spectre of China as the predominant world superpower; the shallowness of modern culture; and the country’s pervasive corruption. Almost everyone in the novel seems open to bribery.

The novel also mocks the state of modern journalism. When Ramesh poses as an online journalist, he claims he works for a leading website where the name of the game is “anything that gets clicks”, listing “Gossip. Bollywood. Pakistan. Saris falling off.”

How to Kidnap the Rich, which has already been optioned by HBO, is an enjoyable romp with some spiky things to say.

‘How to Kidnap the Rich’ by Rahul Raina is published by Little, Brown on 6 May, £14.99

The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock: An Anatomy of the Master of Suspense by Edward White ★★★★☆

There have been dozens of books on Alfred Hitchcock, and finding a new angle must have been a challenge for biographer Edward White. In The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock: An Anatomy of the Master of Suspense, White uses the neat device of looking at the master filmmaker’s character through 12 aspects of his work and life – including “The Womanizer”, “The Voyeur”, “The Family Man” and “The Londoner” – to examine the secrets of the man who made Psycho.

Hitchcock was a fascinating, weird, warped genius. White is unsparing in analysing the director’s creepy, predatory behaviour towards actresses, especially Tippi Hedren during filming for The Birds and Marnie. Hitchcock was out-on-a-ledge bizarre, an individual capable of saying the most brutal things. He told Kim Novak, who starred in Vertigo, “You have got a lot of expression in your face. Don’t want any of it… it’s like taking a sheet of paper and scribbling all over it.” It was a characteristic cruelty from a filmmaker who reportedly described actors as “cattle”.

The book is overflowing with anecdotes, memories and curiosities. The chapter about Hitchcock’s weight problems is hugely enlightening (he had ice cream for breakfast and regular six-course lunches and dinners) and it’s fascinating to learn about Hitchcock’s relationships and collaborations with writers. He nearly worked with Gore Vidal, Harold Pinter and Tom Stoppard; was turned down by Ernest Hemingway and Graham Greene; got along well with Dorothy Parker; and had a fractious working relationship with John Steinbeck. Raymond Chandler dismissed him as a “fat bastard”.

Although he was often grotesque, Hitchcock was also funny. His daughter Pat recalled Hitchcock’s love of ingenious practical jokes, “such as the time he hired an elderly actress – who was in on the joke – to attend one of his dinner parties, where she sat silently through the meal as Hitchcock pretended not to know who she was or why she had arrived, leaving the other guests bemused”.

The book offers lots of insights into what made him such a revolutionary director of masterpieces such as North by Northwest and Rear Window. It’s hard to get near the truth of Hitchcock the man, though. He was a master of manipulation and dissimulation, and although White offers lots of clues to the real Hitchcock, you can’t help feeling that many of the unspoken truths of one of cinema’s strangest masters went with him to the grave in 1980.

‘The Twelve Lives of Alfred Hitchcock: An Anatomy of the Master of Suspense’ by Edward White is published by Norton on 14 May, £22.99

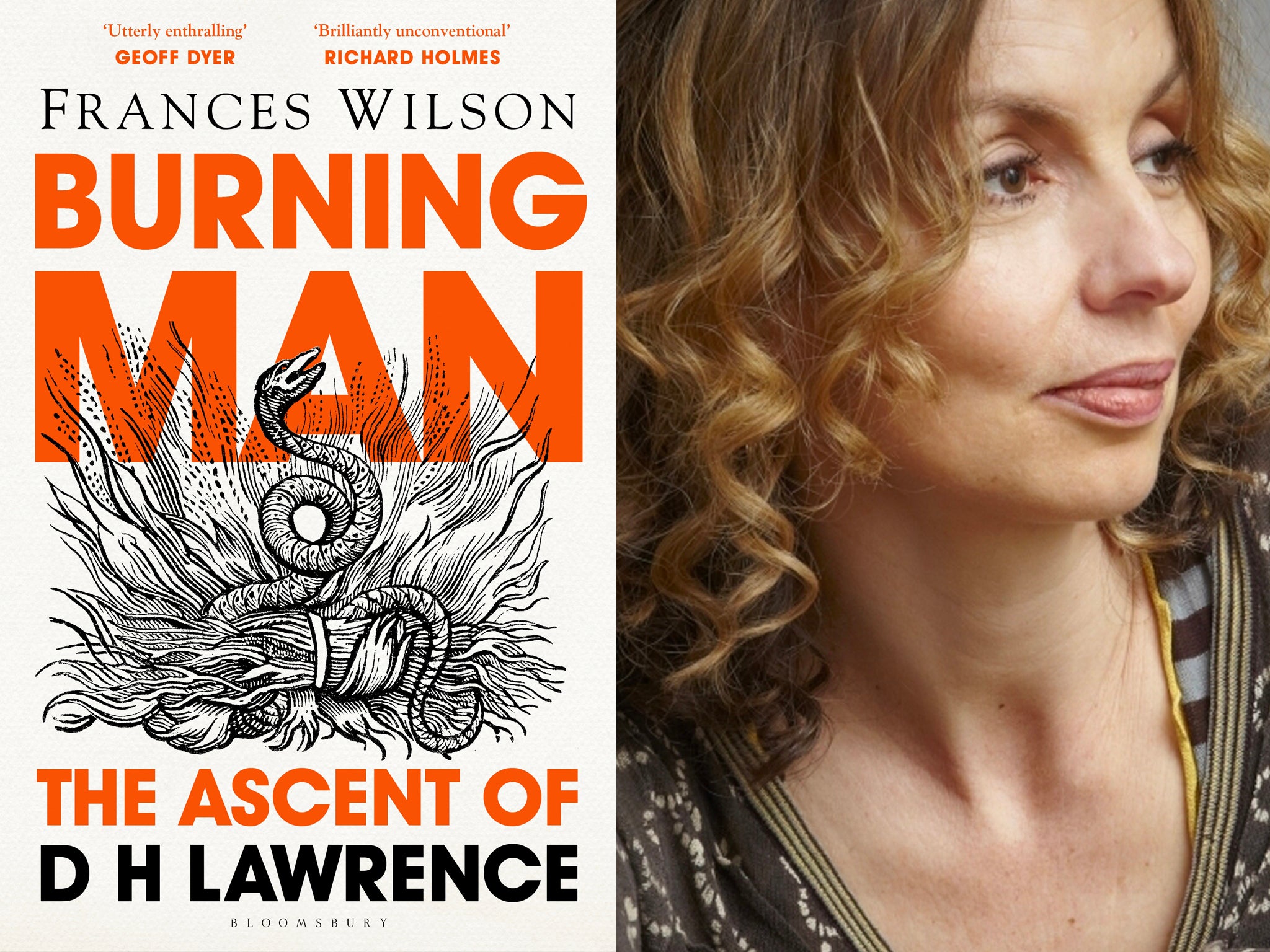

Burning Man: The Ascent of DH Lawrence by Frances Wilson ★★★☆☆

David Herbert Lawrence was a banned author in 1915. More than a thousand copies of The Rainbow were burned in London, and in the 1960s a Glasgow Herald book reviewer was sacked for a positive review and pilloried as a misogynist. According to Frances Wilson, author of Burning Man: The Ascent of DH Lawrence and his first female biographer in modern times, “Lawrence is still on trial”.

Lawrence, the author of Sons and Lovers and Lady Chatterley’s Lover, was only 44 and weighed six stone when he died. He was a sickly child who had grown into a sickly, consumptive man. Wilson captures the ferocity and aggression of this driven author. His words were often spiteful. The London Underground was “a tube full of spectral, decayed people”; Cornish men were “detestably small-eyed and mean – real cunning nosed peasants”, and although Wilson is a fan of his novels, she does not skirt over his failings, describing him as “unhinged”. She analyses his sexual beliefs and attitudes, including his Oedipal feelings for his mother (“I loved her, like a lover,” he told his girlfriend Jessie).

Violence was bred in his bones. His father’s brother killed one son with a kitchen pot, and the writer followed in his own miner father’s wife-beating footsteps. Wilson details the shocking incidents when Lawrence beat his wife Frieda Weekley, pulling her hair and hurling kitchen objects at her. One time he even threatened to smash her head in with a poker.

The biography contains interesting details about his travels and his friendships (especially his fraught relationship with Mabel Dodge Luhan), and the book really hits its stride in dealing with his more obscure writing, such as the unfinished “Great American Novel”. That book was written during a stay in New Mexico, and its discussion is part of the biographer’s stated aim of “revealing a lesser-known Lawrence through introducing his lesser-known works”. There are also nuggets about his writing habits. The author of Women in Love liked to sit beneath an open sky with a pad of paper on his knees, and told a fellow novelist that it was best to write at the same hour every day.

Frieda said it was “sheer willpower” that got him over the Spanish flu epidemic in late 1918 that killed 228,000 Britons. “People were dropping in the streets gasping for air, cities were sprayed with chemicals and the white anti-germ mouth mask became as familiar a garment as a hat or coat. Because porridge was thought to protect you, Lawrence and Frieda lived on porridge,” writes Wilson. Shortly afterwards, Lawrence fled England – a land, he said, of “miserable sodding rotters… a snivelling, dribbling, dithering palsied pulse-less lot”.

Burning Man presents a rounded, empathetic portrait of Lawrence. Will his reputation ever recover? Well, not if any dog lovers read this book and the account of his bizarre, violent attack on a canine called Bibbles.

‘Burning Man: The Ascent of DH Lawrence’ by Frances Wilson is published by Bloomsbury Circus on 27 May, £25

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks