Books of the month: From Blake Bailey’s Philip Roth biography to Richard Coles’s The Madness of Grief

Martin Chilton reviews five of April’s biggest releases for our monthly column

Biography lends to death a new terror,” quipped Oscar Wilde. Luckily Philip Roth wasn’t too concerned about whether a posthumous account of his life raked over his disreputable, incorrigible past. Roth’s main instruction to his biographer was to make him interesting – and Blake Bailey excels in that with Philip Roth: The Biography.

April is an unusually rich month for life stories. In addition to the Roth book, there is also a new biography of acclaimed author Barbara Pym, memoirs by musicians Richard Thompson, Tracey Thorn (writing about her friendship with Australian drummer Lindy Morrison), and a touching memoir by Communards musician-turned churchman Richard Coles. All five are reviewed in full below.

Chris Power’s striking debut novel, A Lonely Man (Faber) is first-rate, about a struggling writer in Berlin, whose life takes a dangerous turn when he meets a ghostwriter for a recently dead Russian oligarch. Power’s previous book was the excellent short story collection Mothers and his latest book is bursting with potent, beguiling prose.

Two other impressive debut novels are Dawnie Walton’s bold, unsettling Final Revival of Opal & Nev (Quercus), a fictional oral history of a 1970s black punk rocker with a complicated past; and Anna Bailey’s psychological thriller Tall Bones (Doubleday), a tale of a missing 17-year-old girl, which delves into small-town prejudice and sinister family secrets.

I also enjoyed Leone Ross’sThis One Sky Day (Faber), a haunting story about grief and love, set in an archipelago called Popisho. Among the many charms of the novel is the way it celebrates the oddness of life. Alaa Al Aswany’s The Republic of False Truths (Faber) is a moving and imagined account of the 2011 Egyptian Revolution. Al Aswany, a dentist who retains his own practice in Cairo, is a beautiful writer (The Yacoubian Building) and this gorgeous novel is translated from Arabic by SR Fellowes. For something more offbeat, I’d recommend A Man Named Doll (Pushkin), in which Jonathan Ames – creator of the TV comedy series Bored to Death – launches a new thriller series about an eccentric LA private detective called Hap.

There are some cracking short story collections this month, the pick of which is Male Tears by Benjamin Myers (Bloomsbury Circus), featuring 18 richly distinctive stories, with unnerving, dark plotlines. Some are brief (“A River” is only 130 words long); all are original, including “Male Tears” about the deeply flawed state of the modern male and “The Folk Song Singer”, a bleakly funny takedown of a male music journalist by a world-weary female singer.

Haruki Murakami is a truly inventive storyteller and his new collection First Person Singular (Harvill Secker, translated from the Japanese by Philip Gabriel) contains some utterly beguiling reflections on nostalgia and loss. Murakami brings his love of baseball and music into the collection, including in the strange story “Charlie Parker Plays Bossa Nova”, which will delight jazz fans. An honourable mention, too, for Louise Kennedy’s The End of the World is a Cul De Sac (Bloomsbury), which contains some biting insights into the grim underside of life in Ireland.

Finally, two history books earn an unconditional thumbs-up. Serhii Plokhy’s Nuclear Folly: A New History of the Cuban Missile Crisis (Allen Lane), based on access to new FBI archives and declassified KGB files, is an enthralling account of a pivotal moment in modern history. It’s replete with startling revelations about the deception and mutual suspicion that brought the US and Soviet Union to the brink of Armageddon in October 1962. While in The Light of Days: Women Fighters of the Jewish Resistance (Virago), Judy Batalion pieces together the true, untold tale of a little-known group of females who took on the Nazis in the face of staggering odds. Batalion’s book honours the “ghetto girls”, who carried out espionage missions, bombed German train lines, and assassinated Gestapo chiefs. The individual tales of these exceptionally courageous young women are remarkable. It’s no surprise the book has been optioned for a film by Steven Spielberg.

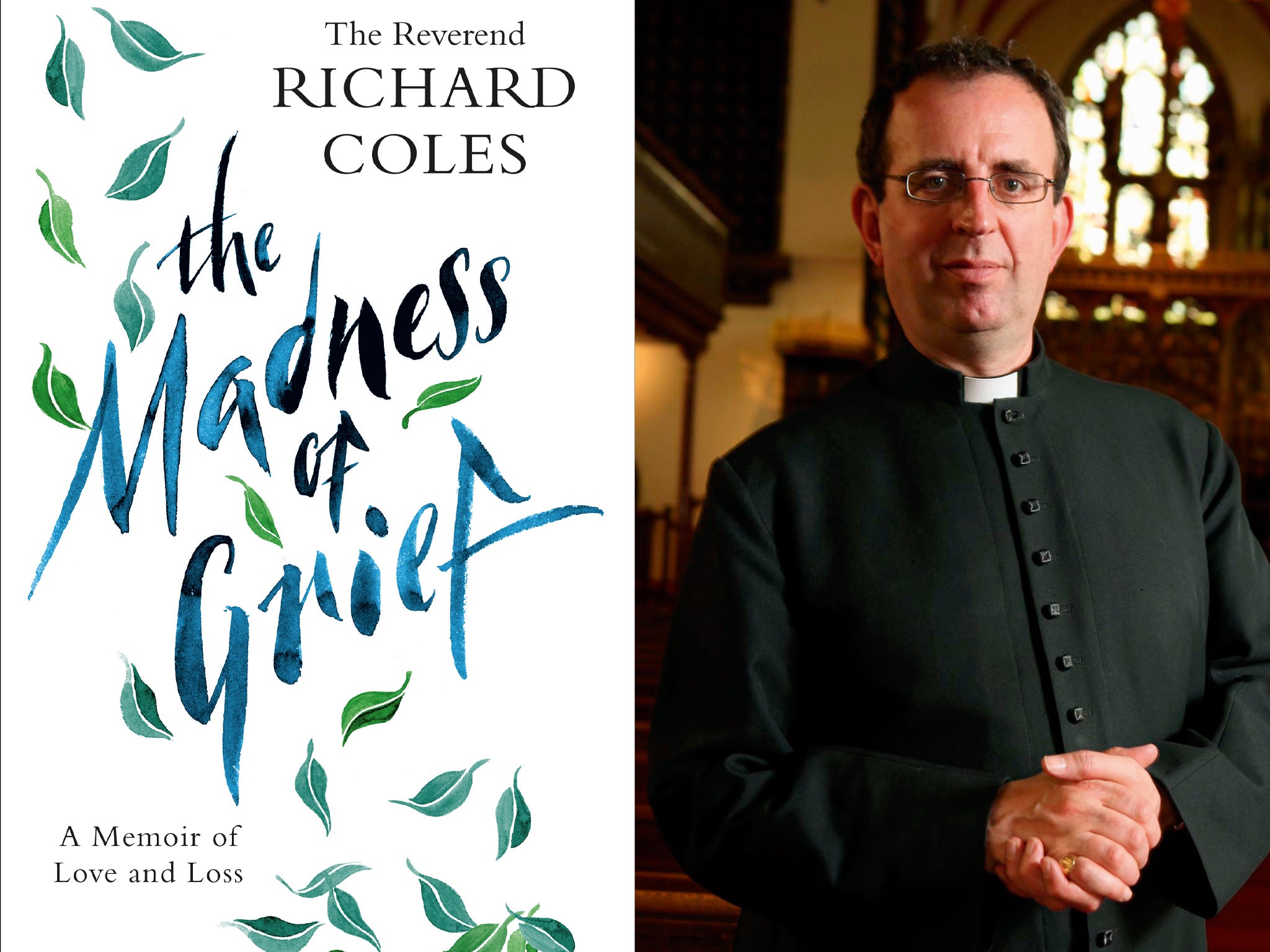

The Madness of Grief: A Memoir of Love and Loss by The Reverend Richard Coles ★★★★★

The Reverend Richard Coles – famous for being a regular host on BBC Radio 4’s Saturday Live and a member of Eighties pop band The Communards – has attended many deathbeds in his life. “Deathbeds came frequently as HIV rampaged its way through our circle of friends and intimates,” he recollects inThe Madness of Grief: A Memoir of Love and Loss.

Shortly before Christmas in 2019, Coles lost David Oldham, his partner of 12 years, who was 43 when he died of a liver disease, caused by alcoholism. Part of the haunting charm of the book is the affectionate, delicate and unsentimental portrait of lost love.

Coles clearly enjoys recalling his civil partner’s impish sense of humour, a man who branded Coles “a borderline national trinket” and would, during heated rows, “mock me and say, sarcastically, ‘Britain’s best-loved vicar?’”. Coles is open about the alcohol addiction that brought Oldham to “the edge of the abyss”; confessing that, at its worst, there was “an episode of such appalling behaviour the police were involved”.

Coles’s musings on joining the ranks of what he calls “fellow casualties of the war with death” will strike a chord with anyone who has grieved. The author captures the pain of looking through old photographs of the dead. He makes you think about the unexpected things you find among their possessions (bottle after bottle of untaken tablets, in this case) and is funny about the grim business of post-death bureaucracy, which he dubs “sadmin”. For me, Coles reignited a memory of the weird experience of having to select a coffin. “I made the selection like someone on a first date in a restaurant, choosing wine not from the bottom of the list, nor the top, but midrange,” Coles writes.

The book shines with the sort of wry, self-analytical wisdom you might expect from Coles, and one surprisingly unsentimental reflection leapt out, as he described the aftermath of Oldham’s funeral. “I thought of his coffin in the earth, not with the handful of dust I had thrown rattling on the lid, but with the three tons of earth unceremoniously dropped on it when the diggers filled it in. He was now six feet under, decomposing, a far more vivid image for me than someone floating through the air towards a dazzling light.”

The Madness of Grief shoots off at tangents – there are stark anecdotes about an IRA bomb, the former SAS soldier who had to guard Steve McQueen’s corpse and his own experience of deranged hate mail – and is full of affecting small details, including the moment he sang Joni Mitchell’s “A Case of You” to his dying lover.

Coles admits that he thinks about death all the time. Saul Bellow once described death as the dark backing that a mirror needs if we are to see anything. Coles’s book is full of resonating reflections, ones that urge us all to be kinder, to love more strongly.

The Madness of Grief: A Memoir of Love and Loss by The Reverend Richard Coles is published by Weidenfeld & Nicolson, £16.99

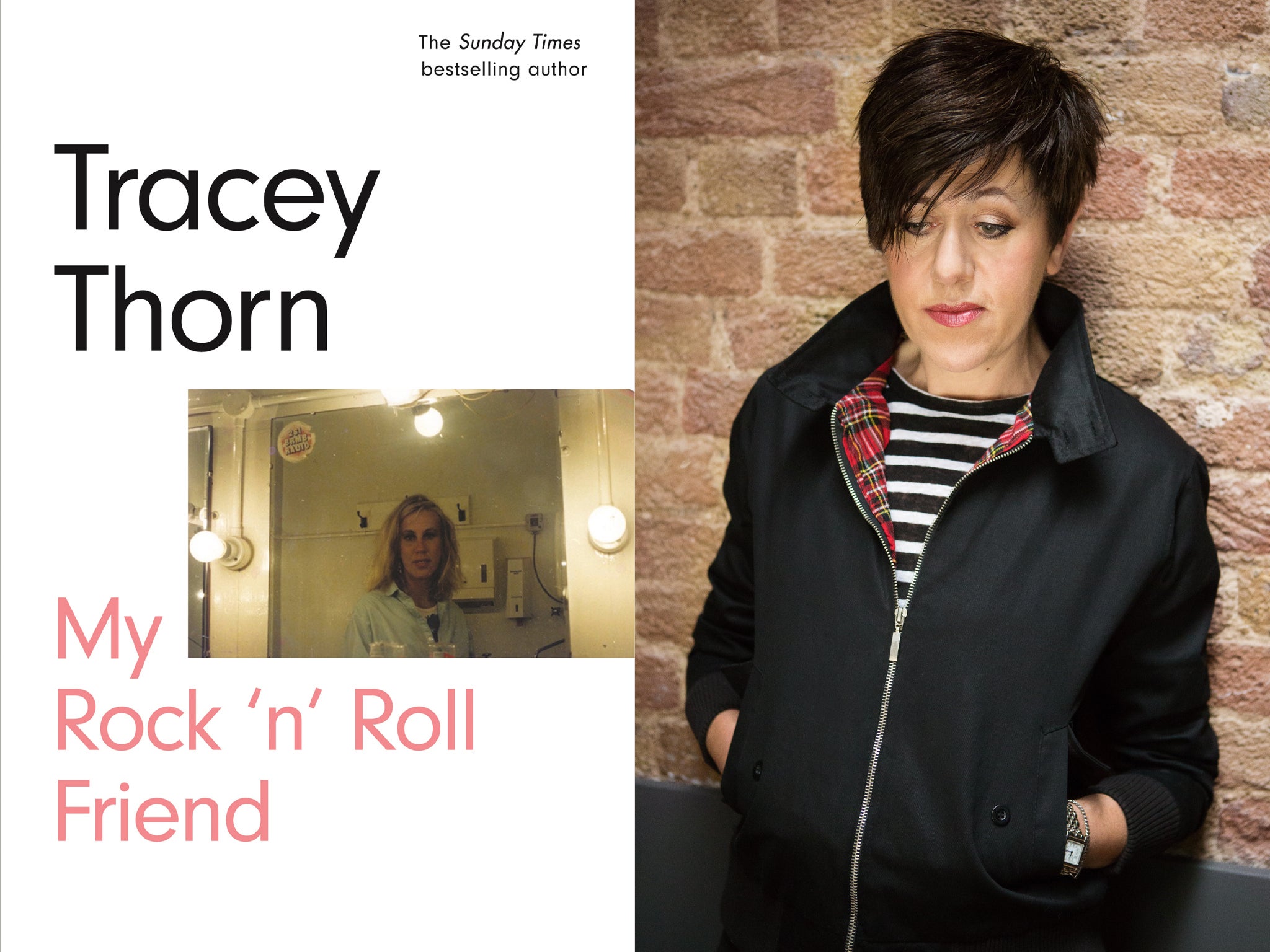

My Rock ‘n’ Roll Friend by Tracey Thorn ★★★★☆

The letters singer Tracey Thorn received from fellow musician Lindy Morrison were rarely dull, including the one in 1997 relating to her affair with a married man. “I was sitting on his cock working out our lives together,” the Australian drummer for The Go-Betweens informed Thorn in her correspondence. This engrossing book, a mix of memoir and social reflection, is Thorn’s attempt to work out their complex, emotional friendship. The book reminds us how much of identity is tied to memory.

After meeting in London, Morrison and singer-songwriter Thorn, part of bestselling duo Everything But The Girl, have been friends for nearly four decades. After a 20-year hiatus, and in the midst of Thorn’s own personal “crisis”, they met again in Sydney in 2019 to piece together the story of their shared past. The introspection makes for an absorbing, tender book, one that is, at times, very funny.

Chauvinist music journalists do not come out well in the book. Thorn has endured her own experiences of being “patronised”, while Morrison was all too frequently characterised as a “difficult woman” by reporters who never bothered to find out about her eventful past (something given its proper due by Thorn, with tales of violence, sexual experimentation, and radicalism). Thorn is more guarded in her own revelations: she refers to giving up drinking after “an unfortunate incident at a Smiths gig” without spilling the beans.

Despite spending 12 years as a key member of The Go-Betweens, a band dubbed “Two Wimps and a Witch”, Morrison was relegated to a peripheral figure when the history of the band was reframed, following her “brutal” dismissal in 1989. Thorn’s account of the break-up of a neurotic band, damaged by messy love affairs and power struggles, is absorbing. But she has wider points to make about the way society has treated Morrison, going back to when the young Aussie was told by a boyfriend that she should be “more feminine”, and advised by her own father to be “more demure” if she wanted to find a husband.

My Rock ‘n’ Roll Friend has lots of pertinent points to make about sexism – and motherhood and female identity – but it is far from a polemic. The book is, above all, a subtle exploration of the complexities of female friendship. Thorn reaches a richer, more rounded understanding of her friend, beginning to understand the contradictions, insecurities, and vulnerabilities that lie beneath Morrison’s fearless energy and outlandish behaviour.

This entertaining book is a glorious reminder of why any of us relish “the sheer f***ing buzz” of being in the company of a beloved friend.

My Rock ‘n’ Roll Friend by Tracey Thorn is published by Canongate, £16.99

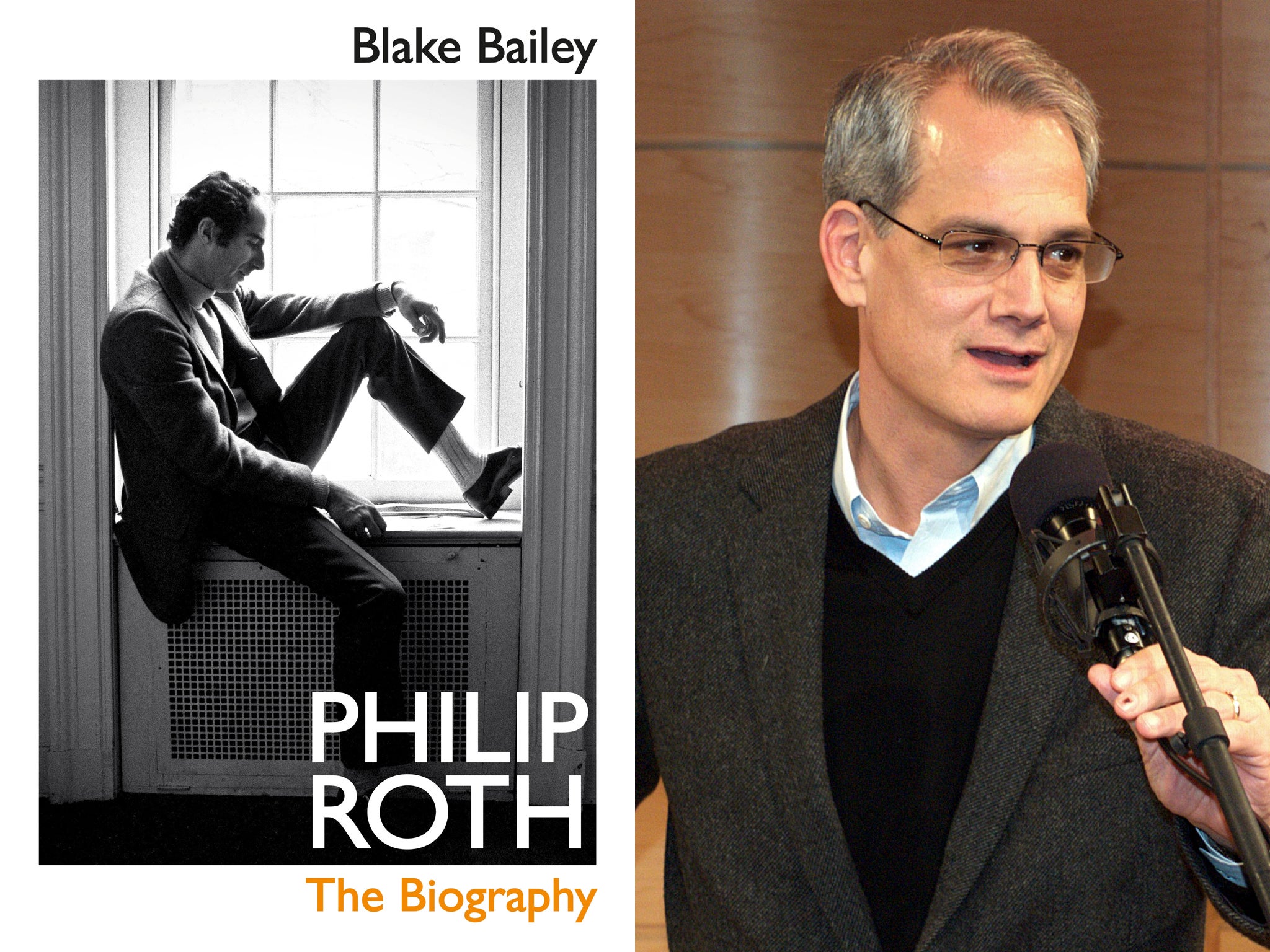

Philip Roth: The Biography by Blake Bailey ★★★★★

Philip Roth’s long-time cleaner Kathy Meetz got to know the award-winning author well during the “morbidly lonely” part of his old age, when he would often dwell on long-held grievances from his fractious life. Roth told her how nice it would be “to sit on a riverbank and watch all the dead bodies of my enemies floating by”.

Roth’s remarkable, tumultuous life deserves a brilliant chronicler and Blake Bailey, the author of an excellent biography of John Cheever, does a magnificent job. Although he acknowledges that he ended up feeling “tenderly” towards Roth, his book is an unvarnished – and therefore damning – portrait of one of literature’s true titans.

Roth, who was 85 when he died on 22 May 2018, used to quote Ernest Hemingway’s dictum that “life is a cheap thing beside a man’s work”. Novels such as American Pastoral, Sabbath’s Theater, Operation Shylock, Everyman, The Human Stain, I Married a Communist and The Plot Against America are masterpieces and will be Roth’s enduring artistic legacy, even though the author’s complex private life reveals a man who was frequently a thoroughly nasty piece of work.

Over 861 pages, Bailey reconstructs the defining influences of his upbringing in a Jewish family in Newark, New Jersey, and the experiences – including a spell writing “snide” movie reviews – that preceded his life as an author. One of the many delights is the score of interesting anecdotes about fellow writers, including Salman Rushdie (“a great writer and an interesting s***”), Norman Mailer (“menacing”), and his great rival John Updike (“he was an ace, maybe the ace”). Some of the most rewarding parts of the book focus on the secrets behind his fiction. Roth was a “fanatic reviser” and it’s intriguing to learn about the way he developed The Plot Against America, especially the pitiful fate of the young boy Seldon Wishnow.

Unsurprisingly, though, it is the controversial love life of the author of explicit fiction such as Portnoy’s Complaint, that dominates the book. We learn in passing of Roth’s visits to sex workers in London and in general about his predatory behaviour towards women. Jill, the girlfriend of former Paris Review editor Nelson Aldrich, remarked after meeting 25-year-old Roth in 1958 that he was a “very funny man but I felt he was always looking up my skirt”.

Women came and went with such rapidity (Roth believed in a “two-year limit to sexual interest”) that he became an expert in the “rock-hard” way of dumping girlfriends. By the time he was rich and famous, his lovers, including three of his students, were usually much younger. “I was forty and she was nineteen; Perfect, as God meant it to be,” he said about dating Laurie Geisler in 1973. “What puzzles me is your need to subjugate women,” his friend Herman Schneider told him a couple of years later when Roth boasted about teaching another young girlfriend how to give a blowjob.

The two most significant relationships of his adult life (outside of those with his mother Bess, father Herman, and brother Sandy) were his two “ugly” marriages. Bailey’s account of Roth’s first, emotionally destructive, marriage to Norwegian Maggie Martinson, a woman the writer considered to be “mad”, skilfully picks apart this fraught, disputed part of Roth’s life, including his troubled relationship with Martinson’s “bewilderingly-raised, love-deprived” children, Helen and Ronald. “If you ever fuck my daughter, I’ll drive a knife right down into your heart,” was a regular refrain in their household. Ah, happy families. There was ice in Roth’s veins. When Martinson was killed instantly in a car crash in 1968, he whispered to her casket, “you’re dead and I didn’t have to do it.” He refers to the man who drove the car in which she was killed as “my emancipator”.

Roth’s second marriage, to actress Claire Bloom, was also toxic and turbulent. His animosity towards his step-daughter Anna (whose father was actor Rod Steiger) was off the scales. The marriage ended in a bitter divorce in 1995, amid allegations over his improper “advances” to Anna’s school-age friend Felicity. For a lot of his time with Bloom, Roth conducted an 18-year affair with a married woman called Inga, who said they shared a “mutual addiction to sex”. She is one of many people who talked openly to Bailey. These personal reminiscences are a big factor in the strength of the biography. “During his London years, Roth would call Inga long-distance and expect her to listen while he masturbated,” recalls Bailey. Although Roth was a shrewd chronicler of human nature in his fiction, his self-absorption meant he missed the signs that Inga had slowly become addicted to alcohol.

Roth exacted literary revenge by pillorying Bloom in a novel. But if you were close to him, you were food for his fiction. Inga became the libidinous Drenka in Sabbath’s Theater. Poet Freya Manfred said that some of her private comments appeared almost verbatim in The Human Stain. “Roth apologised for taping her without her knowledge,” Bailey notes. His depiction of women led to repeated claims of misogyny. It didn’t bother Roth, who joked with Bellow about going to “feminist prison”, and ranted about “man-hating” academic “harpies”.

“Old age isn’t a battle; old age is a massacre,” Roth famously wrote, and Bailey charts the author’s decline, which included mental health problems and suicidal impulses, with sharp-eyed compassion. I remember being moved by Roth’s 1991 National Book Award-winning memoirPatrimony: A True Story, which sparked outrage over his graphic account of the mortifying episode in which Roth’s elderly ill father soiled himself. “I imagined that somewhere down the line, it would be useful to know what it was like to watch someone you love die,” said Roth. Ruthless, or just brutally honest? Bailey presents the evidence and leaves room for readers to make up their own minds about Roth’s character. Along with Roth’s vile behaviour, there are many examples of stunning generosity.

Bailey’s book is so rich in historical detail and psychological insight, as well as wonderful quirkiness – including the writer’s interactions with celebrities such as Bill Clinton, Mia Farrow, Jackie Kennedy, Nicole Kidman, and Penélope Cruz – that it’s hard to see it being surpassed as the definitive account of Roth’s life.

I found Roth’s perfidiousness and “relentless self-justification” exhausting in the end, yet his personality, warts and all, is key to what made him capable of writing such powerful, disturbing fiction. As he liked to say, “there’s no remaking reality.” This is biography at its best and more than lives up to Roth’s instruction to Blake that “I don’t want you to rehabilitate me. Just make me interesting.”

Philip Roth: The Biography by Blake Bailey is published by Jonathan Cape on 8 April, £30

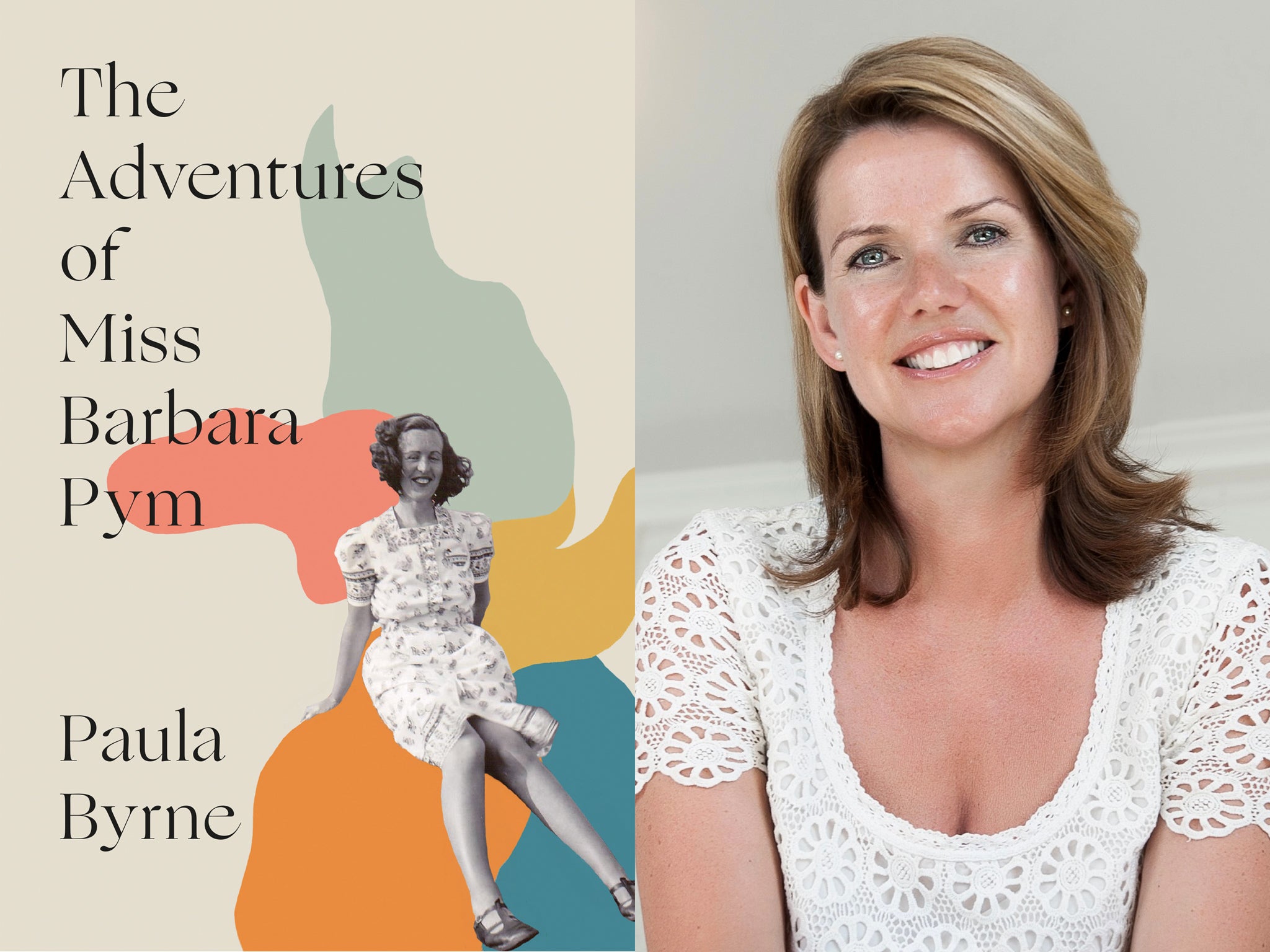

The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym by Paula Byrne ★★★★☆

When John Updike wrote about novelist Barbara Pym, he said it was fair to say that none of her characters could be described as living happily ever after. Although Pym was often hailed as Jane Austen reincarnated, there was a gloominess and steely sharpness to her worldview, especially in the magnificent Sweet Dove Died. It’s clear her fiction was born out of her own troubled life.

Over 686 pages – broken down into 134 brisk chapters –The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym provides numerous new details about the novelist’s unhappy love life. “The more badly men treated her, the more deeply in love she felt,” concludes Paula Byrne, author of two books about Austen. She had access to Pym’s archives and the diaries the Shropshire-born author started when she was 19. Pym destroyed the diary pages relating to one of the most horrific incidents in her past – the time she lost her virginity to fellow Oxford undergraduate Rupert Gleadow, in what was, according to Byrne, an incident “we might now call date-rape”.

Although Pym later played up to the caricature of what she called a “bewildered English spinster”, Byrne is at pains to point out that she was in fact a liberated, independent woman, ahead of her time. Byrne uses Pym’s eventful post-Oxford love life, full of pain and misery, to clarify the factors that shaped her stories.

One of her early affairs was with an SS officer called Friedbert Glück, a friend of Adolf Hitler, and it’s no surprise that Pym later glossed over much of the truth about the extent of her damaging infatuation with Nazism, during a time during she wore a swastika pin. In 1934, aged 21, she attended a “delightful” Nazi rally in Hamburg, later gushing about the way the Fuehrer “looked smooth and clean and I was very impressed”. Byrne says Pym later admitted that she was “ashamed” of her behaviour in this period before she knew about the Holocaust. You can decide for yourself whether a moral verdict on her time as a Nazi groupie is useful.

The account of her “wilderness years” – she went unpublished from 1962 until 1977, a period during which she was worried about her finances, and deeply hurt by the constant rejection letters from publishers – is pieced together well. It was a disheartening time when Pym felt all at sea with the modern world (“Oh, unimaginable horror!” she said of the demolition of Gamages, the famous department store in High Holborn in the early 1970s).

Byrne gives full credit to poet Philip Larkin for the way his steadfast support helped revive Pym’s career in 1977. She died of cancer in 1980 and by then her talent was fully appreciated. The scrutiny of her life reveals a flawed, unhappy personality. I didn’t warm to Pym the person, but the pleasure of Pym’s intellectual company lies in her novels.

The Adventures of Miss Barbara Pym by Paula Byrne is published by William Collins on 15 April, £25

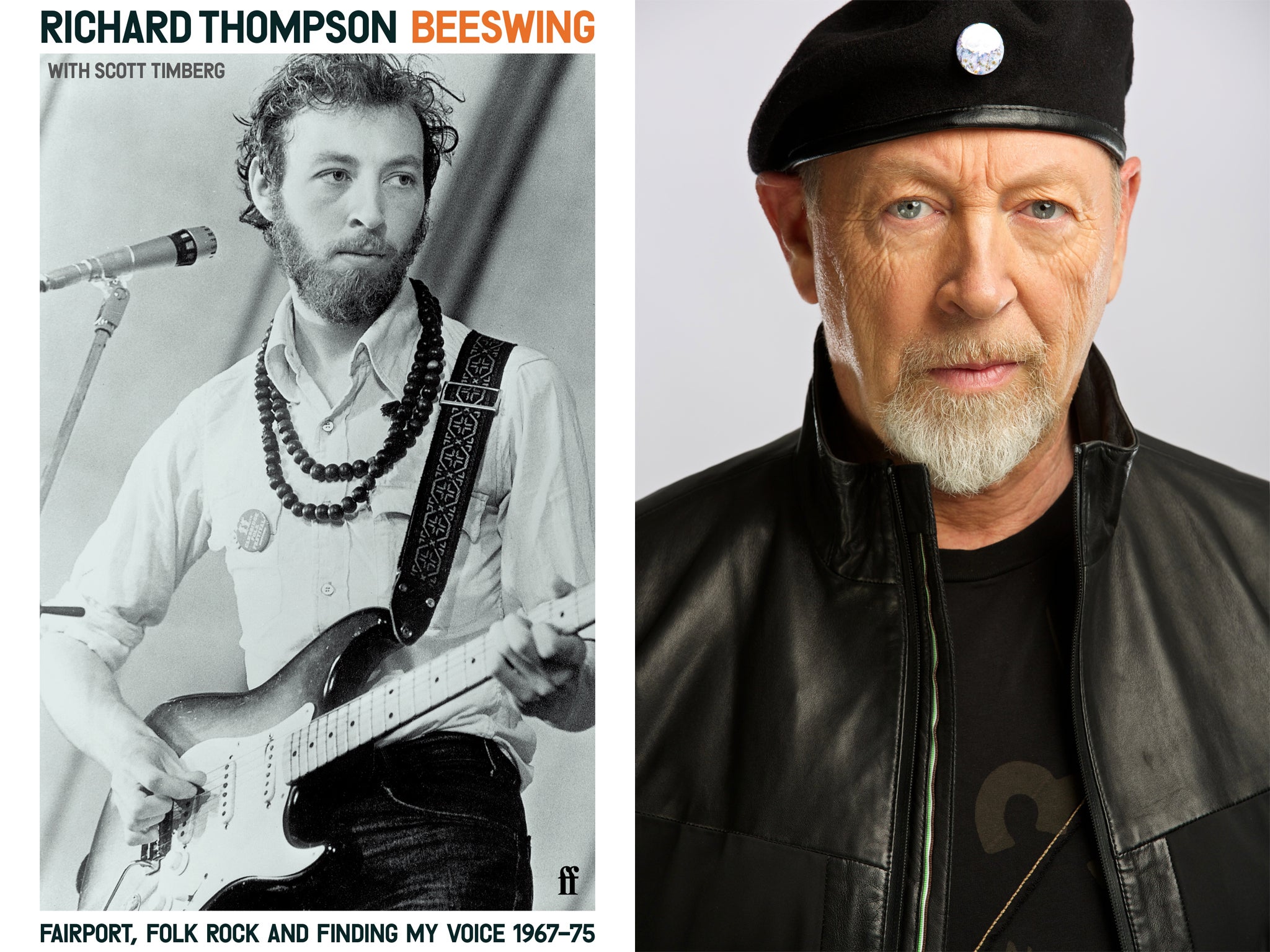

Beeswing: Fairport, Folk Rock and Finding My Voice 1967-75 by Richard Thompson ★★★★☆

Richard Thompson, who co-founded folk-rock band Fairport Convention at the age of 18 and helped invent a new genre of music, is pretty withering in his view of his own industry in his memoirBeeswing, written with the help of the late Scott Timberg. “The music world is full of arseholes – absolute, arrogant, self-serving dickheads who imagine it all revolves around them,” writes the 71-year-old.

Thompson left Fairport Convention in 1971 and went on to build his own solo career as one of the finest guitarists and songwriters of the modern era. Although Thompson notes that “songwriting is a strange business, and those who claim to understand the creative process are usually uttering bullshit of the first magnitude,” he offers a few nuggets about the sources for some of his own songs. “The Poor Ditching Boy” was inspired by the novels of Thomas Hardy; “Turning of the Tide” was inspired by his liaison with a German sex worker in the Reeperbahn. Thompson writes sensitively about folk musicians Sandy Denny, Nick Drake, and John Martyn. He gives a witty breakdown of his disastrous collaboration with the hard-drinking Gerry Rafferty.

When Thompson first toured with Fairport Convention, he recalls that the band all read George Melly’s memoirOwning Up, copying the jazz singer’s vocabulary. “Melly’s descriptions of guest house horrors reflected our own experiences,” writes Thompson. One of the charms of this well-written, shrewd autobiography is that it brings to life a lost world of small clubs, life on the road, and the hand-to-mouth existence of 1960s musicians. Thompson remembers that he once turned down the chance to go to Paul McCartney’s birthday party, adding, “If I could speak to that nineteen-year-old snob now, I’d give him a good shake, tell him not to be so judgemental and get down there and enjoy himself”.

There’s been a fair amount of drama in Thompson’s personal life, including the tragic motorway crash in the early morning hours of 12 May 1969 that killed Fairport Convention’s drummer Martin Lamble (who was just 19 at the time), as well as fashion designer and magazine columnist Jeannie Franklyn (who was dating guitarist Thompson). “Our transit van looked as though a thoughtless giant had stepped on it,” writes Thompson, who conveys the shock, grief and numbness that affected the surviving band members. “In 1969, no one thought of counselling or therapy,” he notes.

Although we learn about his “fractured relationship” with his police officer father, amid the self-appraisal Thompson has a fleet-footed way of sidestepping painful and vulnerable episodes in his life. For example, there is just a brief aside about fathering a child with a woman 10 years his senior, while the tumultuous end of his marriage to Linda – one of the most visceral break-ups in music – is dealt with in one paragraph that ends, “this was a tough time for everyone, especially our children, and the wounds are still healing”. This is more like a spin doctor’s press release than serious introspection.

Those who love Thompson’s music and his shrewd, comical, cynical lyrics, will particularly enjoy flashes of his biting humour, including his account of a bizarre encounter with Buck Owens, the story of his own clog-wearing wedding disaster, and, as the absolute topper, his account of a pilgrimage to Mecca with a group of Pakistani-British worshippers. The disastrous trip, which came after his involvement with Sufi religion, is a memorable account of illness, pestilence, fisticuffs, and a swim in the Red Sea during which a “bloated, headless body of a camel floated by”. The trip surely deserves its own epic folk ballad.

“I’m always trying to figure out why I am the way I am,” remarks Thompson. Although it’s enjoyable to spend time with this restless, questioning mind, you suspect that, in the quest to work out the truth, Thompson is keeping a few cards hidden, perhaps even from himself.

Beeswing: Fairport, Folk Rock and Finding My Voice 1967-75 is published by Faber on 15 April, £20

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks