Books of the month: From August Blue by Deborah Levy to Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer

Martin Chilton reviews the biggest new books for May in our monthly column

Obsessive fans are a curious phenomenon. I must admit that before reading Michael Bond’s Fans: A Journey into the Psychology of Belonging (Picador), I had not heard of “Bronies” – middle-aged men who meet in online communities to celebrate the characters in the My Little Pony toy franchise – and I was also left puzzling about the sort of person who would pay $25,000 for a kidney stone passed by William Shatner. In Fans, Bond looks with a shrewd eye over the subject of fandom through the lens of social psychology. It’s an enlightening read, and a hoot.

Bond also records that a Justin Timberlake devotee once paid £1,025 for a piece of French toast half-eaten by the bestselling pop star. Music fans looking for more vintage fare will enjoy Too Late to Stop Now: More Rock ’n’ Roll Stories by Allan Jones (Bloomsbury Caravel), which contains more than 40 interviews written by a journalist who started with Melody Maker in the early 1970s and went on to launch Uncut magazine.

The profiles include Elton John, Elvis Costello and Chrissie Hynde. There is also a revealing encounter with Sting, whom Jones first met in August 1977, when the singer had recently left the security of a full-time teaching job in a mining village called Cramlington to form The Police. After a hostile reception at a festival in France, a diffident, nervous Sting asked Jones, “Should I just give up?” Two years later, with Gold Discs hanging in his lavatory, success had worked its tantric magic. “I know I’m arrogant. I think it would be false for me to be modest,” Sting told Jones. “I’m a great singer and I know it. I’m a great songwriter and I know it.”

There are striking descriptions of country landscapes in naturalist John Wright’s The Observant Walker: Wild Food, Nature and Hidden Treasures on the Pathways of Britain (Profile Books) – including observations on the Cheviot Hills, Hayling Island and The New Forest – though I was most taken by the chapter “Fulham to Marble Arch”. In this stroll through the capital, Wright, an expert on fungi, guides the reader through a myriad of delights most Londoners probably miss, including the St George’s Mushrooms to be found in Farringdon, the Sea Beet in Dagenham and the Wild Rocket in Hackney.

It is two decades since DJ Taylor won the Whitbread Prize for his book on George Orwell. His fresh study, Orwell: The New Life (Constable), draws on previously unseen material – including recently-discovered letters from the author of Nineteen Eighty-Four to his girlfriends – for a rounded, astute guide to one of the 20th-century’s most important writers. Another major biography out this month that utilises new material is Jonny Steinberg’s Winnie & Nelson: Portrait of a Marriage (William Collins). The study reveals some startling truths behind the fractured and volatile marriage of anti-apartheid activists Winnie and Nelson Mandela.

Fans of comedian Josie Long will savour her take on modern life in the short story collection Because I Don’t Know What You Mean and What You Don’t (Canongate), which includes a satirical view of life in a cul-de-sac, where the locals spend their time discussing eggs via their WhatsApp group. A collection I would particularly recommend is Jolene McIlwain’s Sidle Creek (Melville House), complex and elegantly written stories set in a quirky Appalachian landscape.

My favourite book in translation this month is Paolo Milone’s The Art of Binding People (Europa Editions, translated from the Italian by Lucy Rand), the arresting memoir of a psychiatrist who worked on an emergency mental ward. As well as the tales of strange patients – one constantly plays imaginary tennis in the corridor, imagining, with no shortage of ambition at least, that he is competing at the Italian Open – the poetic ruminations give a real insight into the pain of battling and treating mental illness. “Psychiatry is one big game of snakes and ladders,” observes Genoa-born Milone.

Novels by Deborah Levy, Claire Kilroy and Jen Beagin, posthumous essays by Barry Lopez, Rebecca Simon’s history of pirates and Claire Dederer’s study of predatory male monsters are reviewed in full below.

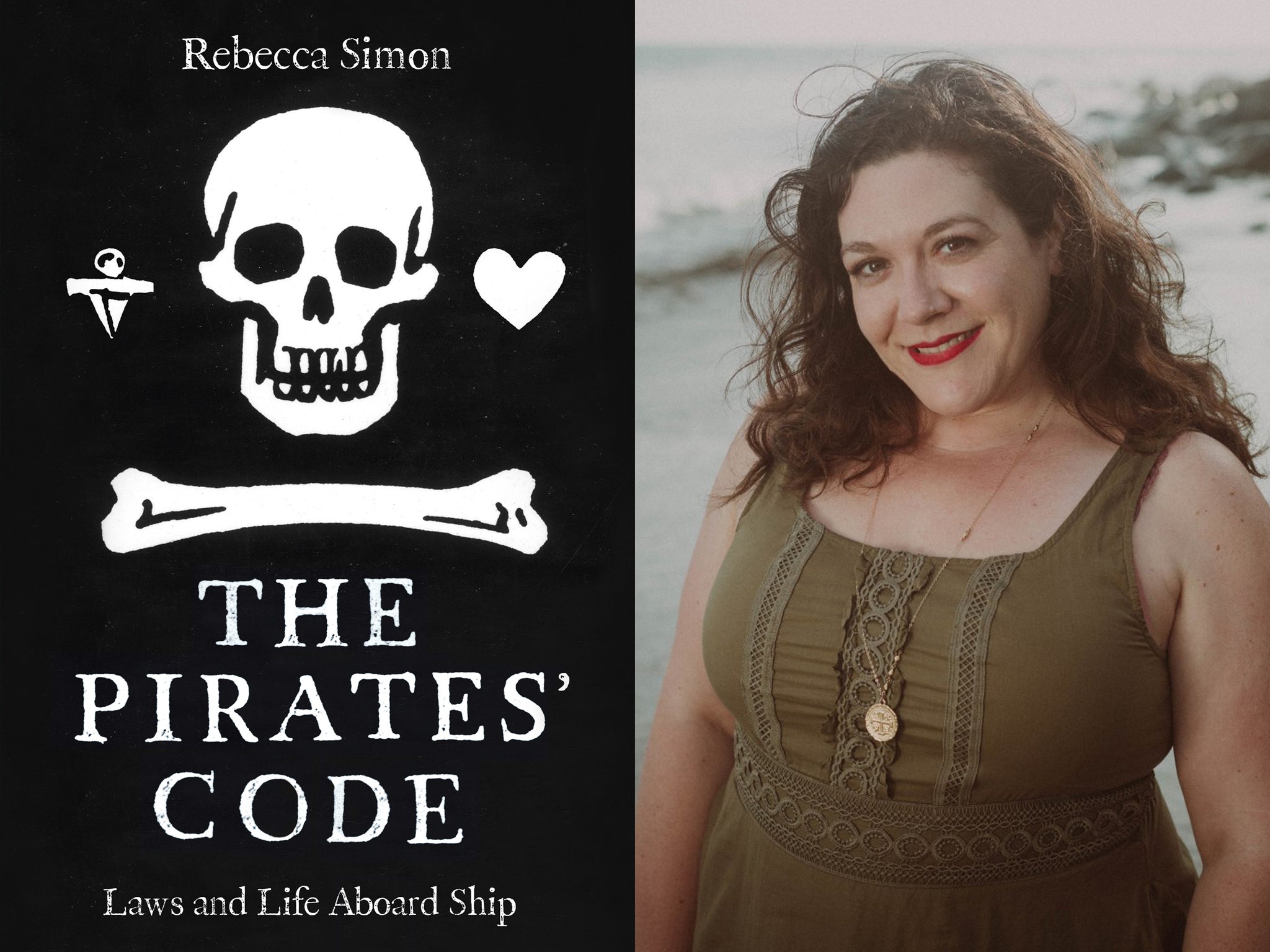

The Pirates’ Code: Laws and Life Aboard Ship by Rebecca Simon ★★★★☆

Horatio tells Hamlet how “a pirate of very warlike appointment gave us chase,” capturing the real threat in Shakespeare’s day of buccaneers targeting sea travellers. A century later and the terror had only increased: in The Pirates’ Code: Laws and Life Aboard Ship, Rebecca Simon, Professor of History at Santa Monica College, estimates that there were up to 2,400 pirates sailing around the Atlantic Ocean by 1718.

What was life really like on a pirate ship? In her impressively researched book, Simon offers an engrossing account that goes well beyond the romanticised Johnny Depp/Jack Sparrow view of life as a criminal on the high seas. Her chapters on health and safety, sex and relationships, weapons and battle tactics, and entertainment on pirate ships are particularly enlightening.

Pirates were actually a diverse bunch – and their society was not totally lawless. Their ships were often egalitarian. If the pirates believed their captain was unfit to rule, they could vote him out and select someone new. Black pirates, many of whom were escaped slaves, fared better than in so-called civilised society and, explains Simon, “were often just as valued as the rest of the crew members and received their fair share of plunder as payment”.

There is a lot of grisly information about the punishment techniques – keel-hauling, marooning, woodling, maiming and forced cannibalism among them – including one that is horrid enough to make any man’s eyes (salt) water. Pirate transgressors were sometimes hung by their genitals, “til the weight of their bodies tore them lose”. I don’t remember seeing that in Peter Ustinov’s jolly movie about Captain Blackbeard.

Of course, “modern piracy” is still with us – 132 ships were attacked in 2021 – but for a rollicking account of the reality of the “Golden Age” of piracy, Simon’s book should float your boat.

The Pirates’ Code: Laws and Life Aboard Ship by Rebecca Simon is published by Reaktion Books on 1 May, £15.99

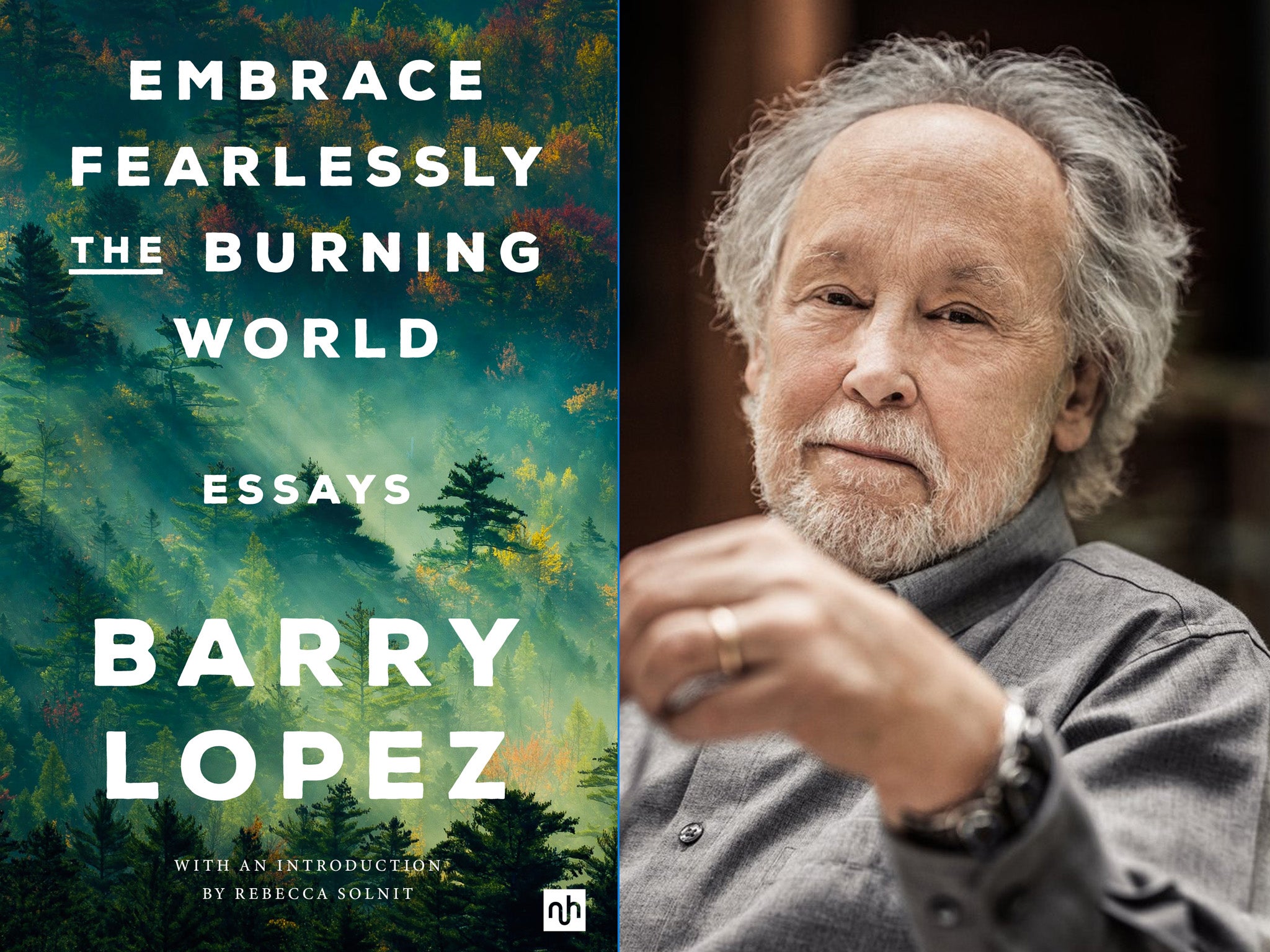

Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World: Essays by Barry Lopez ★★★★★

National Book Award winner Barry Lopez died of cancer, aged 75, on Christmas Day, 2020. Now he is celebrated with a mesmerising, posthumously published collection of 26 essays, Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World, which features an introduction by Rebecca Solnit.

Lopez had an enquiring, original mind, and among my favourite essays is “An Era of Emergencies is Upon Us and We Cannot Look Away”, in which Lopez argues eloquently for a new kind of civilisation, “one more cognizant of limits, less greedy, more compassionate, less bigoted, more inclusive, less exploitative” – and one not propped up by “the ethical obtuseness of the king’s adoring enablers”.

He loved exploring the edges of the world and the book includes vivid accounts of his trip on an ice-breaking vessel in Antarctica, training as a scuba diver and observing walruses in the wild (one experience of helping save sea lions provides a truly extraordinary mystical moment). Again and again, he reminds you of the “therapeutic dimensions of a relationship with place”.

Lopez also has a remarkable capacity to look into the dark recesses of the human mind. In the essay “¡Nunca Má”, originally published in 2008 in the Pacific Journal of International Writing, Lopez reflects on the bewildering experience of visiting Auschwitz, a site of “industrialised murder”. As he walks through the site of Nazi horrors, he feels an onset of panic, “as if I were suddenly trying to swim in gasoline”. The experience makes him reflect on the “genocidal origins” of the United States (something that “remains, regrettably, a region of political oblivion”), a subject explored in the powerful “Out West”, written after his trip to “the slaughter grounds” where Native Americans and their animals were killed in such staggering numbers.

The essay that scorched itself into my mind, however, is the one in which he deals openly and bravely with his harrowing childhood. After his mother split from a violent bigamist father, Lopez fell prey to Harry Shier, a fiftysomething doctor who ran drying out clinics for alcoholics in North Hollywood. He groomed the family and raped the author for years, crimes that started when Lopez was just six.

In the 2013 article “Sliver of Sky”, Lopez describes what it like to be a sexually brutalised child, living in silent compliance. He pieces together how the respectable Shier was able to groom children, in a way that explains Jimmy Saville’s modus operandi. “A reputation for valued service and magnanimous gestures often forms part of the protective cover paedophiles create,” Lopez comments. The account of how his mother reacted when he finally tried to talk about his horrendous past is one of the most heartbreaking passages I have read for years.

Despite the deep sorrow, the book is one that overflows with compassion. You finish the book awed by Lopez’s quest for understanding the predicaments that nearly everyone encounters, at some level, at some time, in their lives. I was enthralled by embracing his fearlessly burning mind.

Embrace Fearlessly the Burning World: Essays by Barry Lopez is published by Notting Hill Editions on 2 May, £12.99

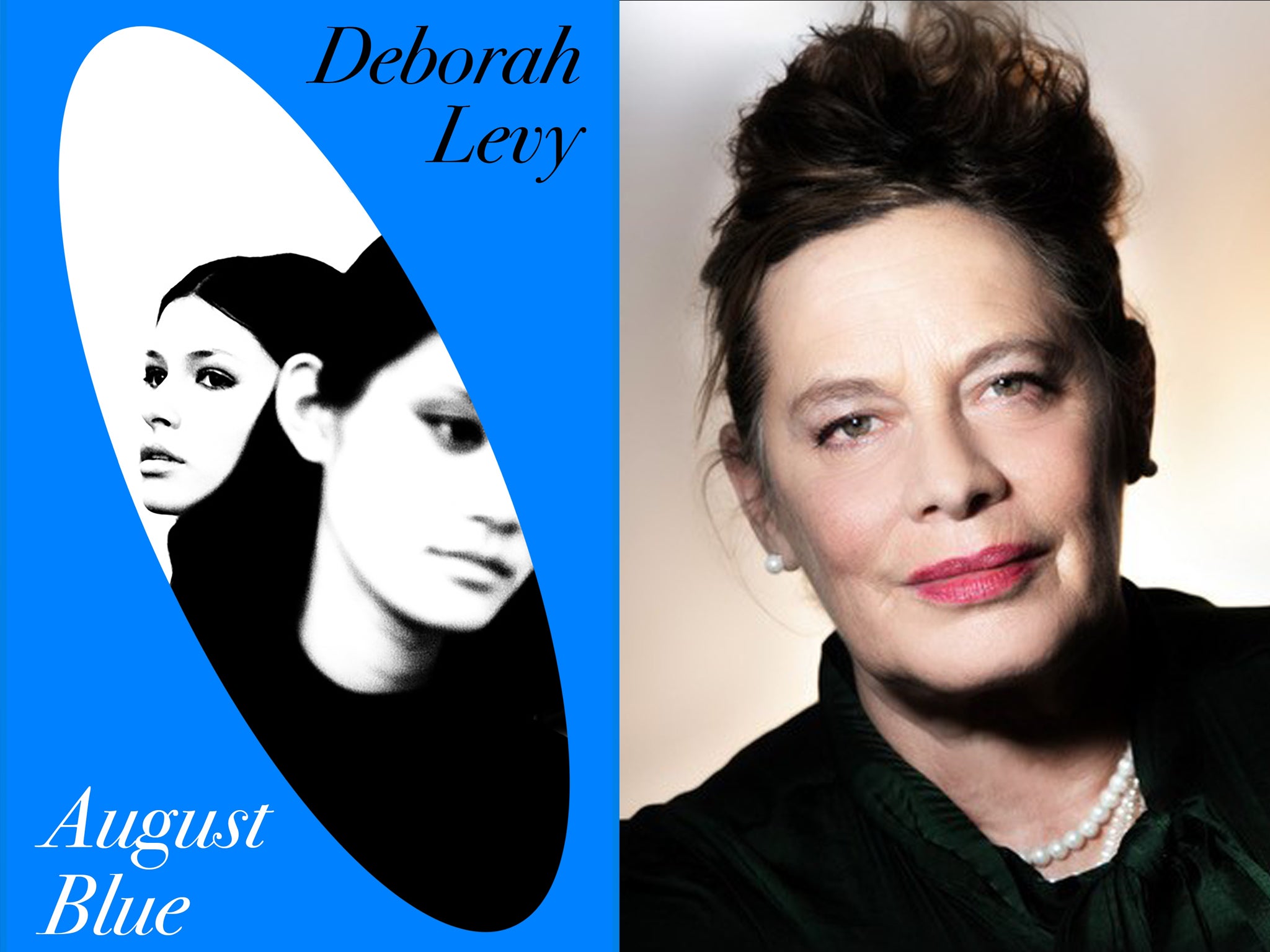

August Blue by Deborah Levy ★★★★★

After the public humiliation of walking off stage during her performance of Rachmaninov’s Piano Concerto No 2 in Vienna, virtuoso musician Elsa M Anderson, unmoored and crushed, embarks on an odyssey of discovery across pandemic-hit Europe. She admits she has “lost her nerve”.

Deborah Levy is a master novelist and in August Blue, a beguiling story of how identities collide and crack, she shows us what it feels like to be a divided self. Elsa, who was raised to be a virtuoso pianist by a “merciless” teacher, has reached 34 without ever really confronting her origins: the mother who gave her up, the unknown father and the foster parents she rejected.

The disaster in Vienna, and her own unsettling experience of encountering a mysterious doppelganger, force her to confront what she wants out of life, or whether she even wants to continue with it. Levy’s beautifully atmospheric novel – set in Greece, France, London and Sardinia – succeeds as a dazzling portrait of melancholy and renewal. The cover design is gorgeous and the writing exquisite. Towards the conclusion, Elsa ponders on the meaning of two young people kissing by a bus stop. “Frantic kissing. As if this devouring of each other was an existential duty. The obligation to keep the life drive going strong when death is our ultimate destiny.”

August Blue by Deborah Levy is published by Hamish Hamilton on 4 May, £18.99

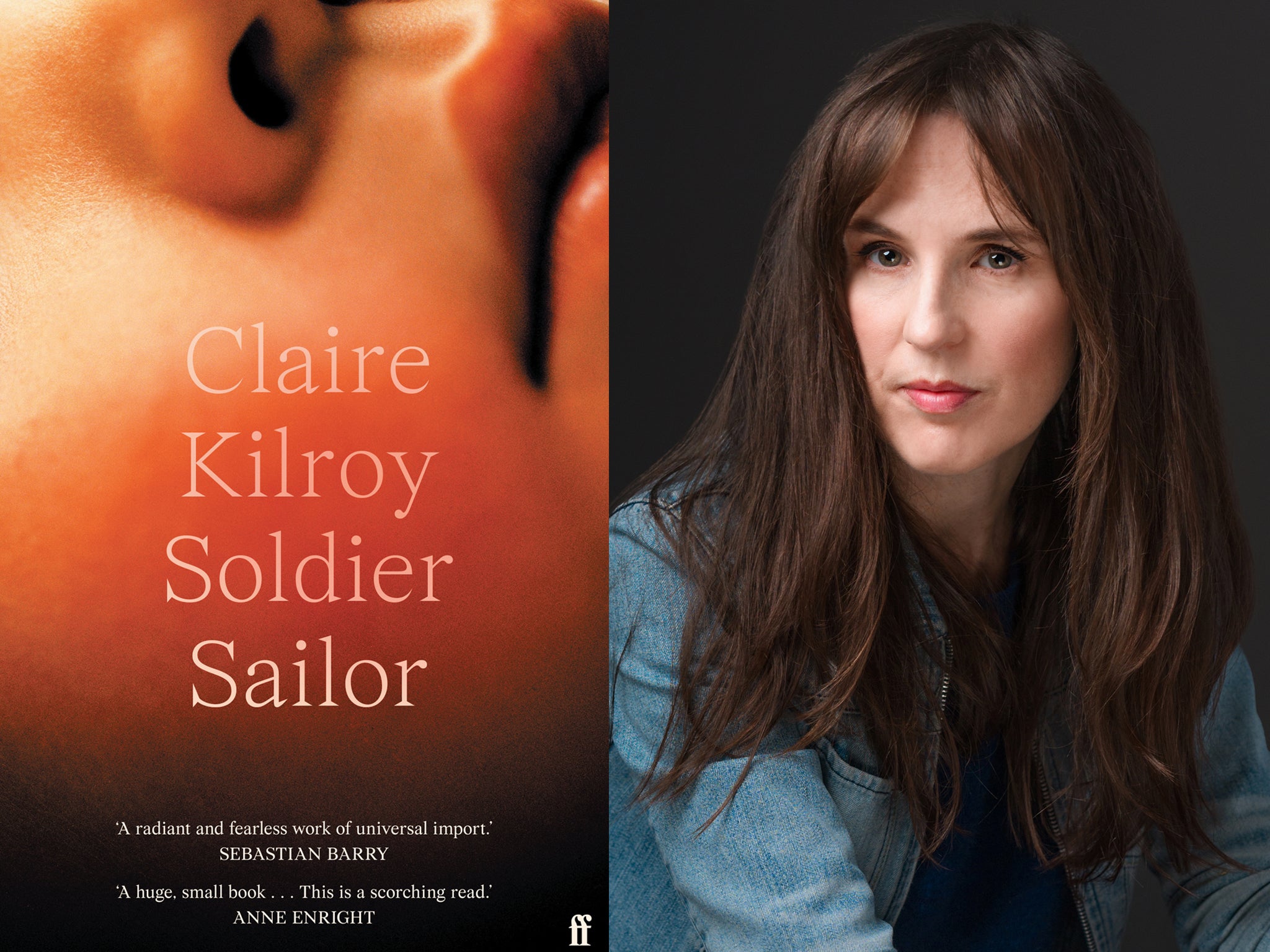

Soldier Sailor by Claire Kilroy ★★★★☆

Claire Kilroy, who gave birth to a son in 2012 when she was 38, described motherhood as “the hardest and most daunting thing I have done in my life”. Soldier Sailor, a blistering novel about a new mother, hits with the force of a lightning strike.

This brilliant work of fiction is the Dubliner’s first novel since 2012’s The Devil I Know. She began it around 2018. Until then, of course, she had scant time for writing, forcing her to put aside the opportunities to create what she calls “those small miracles when a door swung open on to a room in my imagination” in order to raise her child. She stored up some small miracles in those “lost” years, thankfully, and her lyrical depiction of a life of trudging drudgery, told in countless tiny telling details, will surely clang loud bells for all the mothers who see their own frustrations highlighted in this bleak, angry and enchanting novel.

Soldier Sailor is a fearless book, one that treats motherhood as a serious literary topic, and Kilroy’s deceptively simple way of capturing the roller coaster of turmoil and joy, the quickly changing emotions that result from the thin membrane “between coping and not”, possess a haunting power.

Kilroy is clearly angry about how so much of parenting falls to the woman and a sense of rage throbs throughout the book. It’s a strange thought, however, that nearly all the sleep-deprived, housework-and-childcare-burdened mothers will probably be too busy raising kids to have the time to read such a resonating novel. Perhaps the type of domestic duty escaping father presented in the book should be shackled the moment they attempt to leave their house with golf club bag in hand, and then be forced to listen to an audio version read by their own exhausted partner.

Over and over, Kilroy skewers the patriarchy and the self-absorbed men who benefit from it. Any father worth his salt will surely shudder with remorse in recognising some of his own failings. Kilroy presents the bigger picture, too, acknowledging the way a patriarchal society fosters this gender disparity in parenting, encouraging absent fathers to hide behind the justification of having to work hard. “Your bosses promote you for shirking family responsibilities while your wives’ careers dwindle to a halt because somebody is left handling the baby,” says the protagonist (referred to by her nickname Soldier) to her husband.

In the novel, a chance meeting with an old friend reminds Soldier of what life used to be like, and she starts to confront what it means to be “banished from the adult world”. Soldier constantly advises her son Sailor, a wonderfully depicted pickle of a toddler, not to be a dick. “Don’t be one of them,” she pleads. She calls her husband “the enemy within”, and in truth it is hard not to view the husband in the novel as a prize dick. The strain on this fictional marriage because of his emotional juvenility is palpable, summed up by his obdurate, obtuse behaviour during a fraught shopping trip to an Irish Ikea. The scene is memorably – and painfully – funny and sharp. Later, there is a stark, revealing moment when, oblivious to his wife’s panic and fear at the sudden illness of their child, he simply rouses himself “up on to his hind legs to shut the bedroom door”.

Perhaps “mum’s-life-is-s*** lit” may not catch on with the popularity of chick lit, but rarely has the everyday experience of child-raising, presented from a first-time mother’s standpoint, been executed with such depth and grace. And although Soldier Sailor is a book that burns, the final moving 10 pages are a glorious reminder of the inescapable joy of being stuck with a tiny human ball and chain.

Soldier Sailor by Claire Kilroy is published by Faber on 4 May, £16.99

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer ★★★★★

“Could Lolita be published today? I doubt it,” asks Seattle-based Claire Dederer, a first-class writer who describes herself as that “weird beast… a professional critic”. Her new book Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma is an enthralling, challenging and downright unsettling interrogation of cultural titans in the era of #MeToo. Dederer wants us to think deeply about the struggle to separate the maker from the made.

It surely needed to be a woman who wrote this book – Dederer lists her own #MeToo moments, including being subjected to two attempted rapes and “multiple physical assaults on the street” – yet, as it happens, Lolita author Vladimir Nabokov is judged by Dederer as “a kind of anti-monster” because his 1955 novel is ultimately less about paedophile Humbert Humbert than it is about what it is to steal a childhood. Dederer calls the novel “the world’s most adept depiction of the erasure of a girl”.

The author, looking at her own role as a parent, discusses raising children in a world that, at times, seems “teeming with predators”. She skilfully, thoughtfully – and with balance – dissects some of these famous monsters, men whom she considers to be “black holes”. One subject is Woody Allen (“I took the f***ing of Soon-Yi as a terrible betrayal of me personally”), and details what she claims is the knowing way he artistically groomed his audience with Manhattan, a film about a 42-year-old man’s affair with a 17-year-old student.

The chapter on Roman Polanski is a key one. “There is no other contemporary figure who balances these two forces so equally: the absoluteness of the monstrosity and the absoluteness of the genius. Polanski made Chinatown, often called one of the greatest films of all time. Polanski drugged and anally raped 13-year-old Samantha Gailey,” Dederer records, skilfully navigating the tight rope of intellectual fairness as she concludes that while Polanski was a monster, Rosemary’s Baby is marvellous and has a “startlingly feminist vision”.

Dederer knows how to land a devastating punch. She takes apart artist Pablo Picasso (“the used-up women in his life make a fleshy pig-pile”) and author Ernest Hemingway (“like Picasso, he created a kind of multi-car pileup of women over the decades”) with panache.

Monsters is a vital book for our times, and it offers so much rich food for thought. Dederer knows she is not alone in grappling with the issue of whether you should deprive yourself of Chinatown or Annie Hall because this peerless art was made by monstrous men. She also muses on whether the “stain” of rancid, predatory behaviour works backwards. Should we boycott the music of Michael Jackson? Can we see the humanity even in monsters?

Dederer is candid about her own life – especially when she looks at the issues of drinking and “negligent” motherhood – and also offers smart and provocative views on JK Rowling, “cancel culture” and our own compromised position in a capitalist society that leaves us with “tragically limited roles as consumers”. She shows us the unfiltered picture of what it is like to live in an internet-frenzied world where we are growing more “enmeshed” with public figures by the day. If all this seems too heavy, that is misleading. Dederer is a wonderfully accessible and entertaining guide. And she is witty.

She knows that she is dealing with complex issues. You are left musing along with her about why, in the main, Virginia Woolf gets such a pass for her anti-Semitic views. In Woolf’s case, this is muddied further by the fact that she called her own Jewish husband, Leonard, “my Jew”. Overall, however, and not just with Polanski and Allen but with David Bowie, Miles Davis and others, you are left with a complete understanding of why Dederer states that she has spent her entire life “being disappointed by male artists”.

I would imagine that for women readers Monsters is a book that will strike loud, wounding chords. Those men who read the book should perhaps nod in agreement with the author John Banville, who said (in a quote that appears in the book), “if I were a woman I’d be so furious all the time”.

Monsters: A Fan’s Dilemma by Claire Dederer is published by Sceptre on 11 May, £20

Big Swiss by Jen Beagin ★★★★☆

“I’m here because I’ve never had an orgasm in my life, even by myself,” 28-year-old Swiss-born gynaecologist Flavia tells Om, her sex and relationship coach. Greta, the divorced 45-year-old transcriptionist of these therapy sessions, is instantly hooked, especially when she learns that Flavia had previously suffered an horrific assault at the hands of a violent psychopath.

When Greta accidently meets Flavia, whom she has dubbed “Big Swiss”, at the dog park, she pretends to be a woman called Rebekah and flirts with the intense and compelling beauty whose voice she knows intimately. As they begin a love affair, a dangerous game of secrets, power struggles and false identity is set in motion and things begins to spiral out of control.

Big Swiss, the third novel from talented author Jen Beagin, is being made into a television series by HBO, and Killing Eve star Jodie Comer seems inspired casting for the titular protagonist. The novel is set in Hudson, New York (a place that has always been “crawling with drunks and sluts”) and what makes it such a captivating, jaunty novel is that all the characters seem, well, absolutely unhinged. Flavia’s oddball husband collects shivs confiscated from prisoners. Even the ancient ramshackle house that Greta shares with the eccentric Sabine is crazed, infested with spiders, bees and even maggots.

It is a difficult skill to be naturally and genuinely witty as a fiction writer, but Beagin has, as they say, the chops. Big Swiss is raunchy, rude and downright funny. Flavia tells Om that she finds hand jobs and blows jobs to be a chore, “sort of like walking the dog and drinking wheatgrass at the same time”, one of many occasions when the male ego is punctured with devastating effect in the novel.

The author neatly uses humour as a balm for pain, though. Greta, whose mother killed herself when the teenager was on a dire summer camp trip, tells Om that she cannot forget that on the journey there, “a moustached man in a red convertible drove alongside the bus with his cock out and a big smile on his face”. “Old-school pervert,” Om scribbled. “Magnum PI vibes.”

In among the jokes and the delight in the weirdness of human nature, Beagin delivers a moving love story and a highly original examination of identity, infidelity, mental health, gender and sexual stereotypes. It is also about the difficulty of forgiveness – of oneself as much as of others. “I don’t accept apologies,” Big Swiss says. “Sorry is just something you take off a shelf.”

You won’t be sorry for revelling in this highly original novel.

Big Swiss by Jen Beagin is published by Faber on 18 May, £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks