The goal of Falanx is to help companies defend themselves against cyberattacks

Ethical hacker Rob Shapland has to be able to think like the villain without turning into one himself, writes Heather Martin

We all thank our lucky stars that Sherlock Holmes resisted the call of the dark side, and that crime writers settle for acting out their grim fantasies on the page. I felt much the same about Rob Shapland when I met him for coffee at The Hoxton hotel in London. Not least because it was evident that should he so choose, there was nothing about me that he could not find out.

But I wasn’t too worried. Not only is Shapland bound by the beauty of contracts, he struck me as an ethical kind of guy. All part of his persona, of course, especially when it comes to “pen attacks”.

Shapland is head of innovation and ethical hacker at Falanx Cyber, which specialises in protecting organisations against hackers of the unethical variety. He has to be able to think like the villain without turning into one himself. “Falanx’s goal is to help companies, mostly SMEs, defend themselves. We have solutions that we know work, because we do the attacking as well.”

According to Shapland, the only difference between an ethical hacker and a dark hacker is a consent form. “Everything else is the same.” Only not quite. “There’s always a line I can’t cross, but a criminal hacker can. I can’t bribe someone, I can’t threaten them, I can’t blackmail.”

Shapland became a “pen tester” with First Base Technologies after two “boring” years in business straight out of university. He admits he had a laugh at the word “penetration”: in this case, dressing up and breaking into places, with consent. First Base was founded in 1989 as the first ethical hacking company in the UK, specialising in attack, and acquired three years ago by defence-focused Falanx Cyber; perhaps Shapland was the asset they were after. Back in 2007 he was “new to the industry but clever enough to learn”, recruited as much for his linguistic as his computing skills, perhaps too because he is fit and personable without drawing unnecessary attention to himself. The young Rob did business studies, computing, economics and English language at A-level, and had always enjoyed creative writing; his love of reading was nurtured by the bedtime stories he was raised on. Perhaps when he retires from special ops he’ll become a novelist or scriptwriter.

He describes how he was once recruited by a pharmaceutical company to steal their most valuable piece of data. First, he used LinkedIn to identify a range of employees. Then, posing as a member of the HR team, he went phishing for a username and password, striking gold with one of the directors. He supplemented this with the contact details of an IT person at head office, chosen because a quick trawl of his social media showed him at an airport about to fly out of the country. Head office was large and remote, which lowered the risk of recognition.

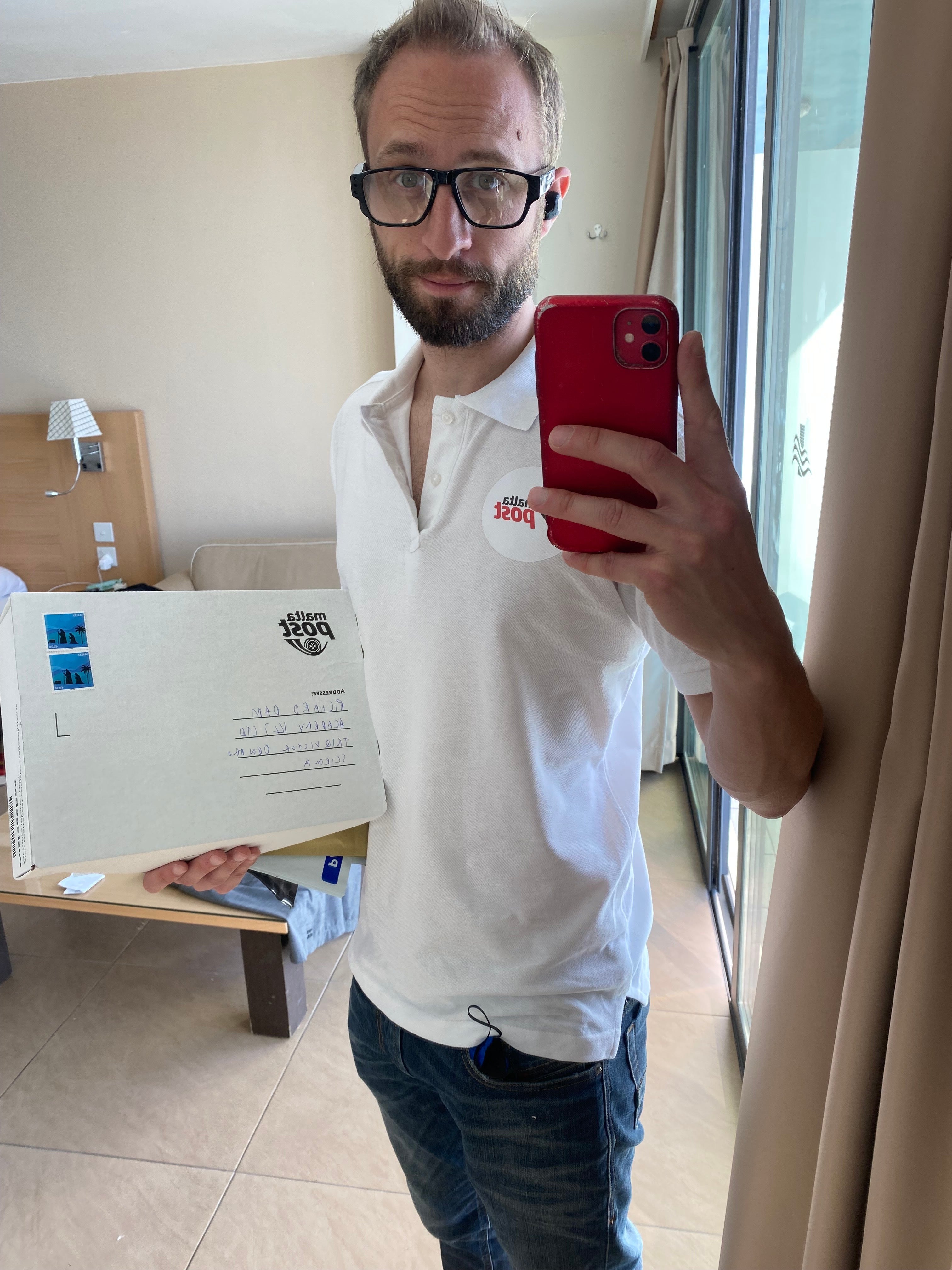

Next he consulted his wardrobe, deciding which of his playbooks – engineer, cleaner, employee, postman, courier – was most suitable. “We call it the pretext: what we’re going to wear, who we’re going to be, how we’re going to get in. The pretext has to match up with your objective once you’re inside.” Friendly but forgettable is what he aims for. “You can play the role of forgettable. It’s part of the outfit.”

On this occasion he opted for the persona of telecoms engineer. He had the uniform ready to go, complete with hi-vis jacket, logo and ID badge, plus a box of tools and cables and a clipboard with some work reference numbers on. He looked the part. No wig and make-up, like the actress he’d teamed up with on occasion in the past. Yet convincing all the same.

But the receptionist isn’t convinced. “There’s been a network outage,” he tells her, “and your head office has called me to come in and fix it for you. Do you mind if I connect into your network?” There’s nothing in her diary, and it’s the first she’s heard of any outage. Shapland supplies her with the number of the head office guy and persuades her to ring it, which she does, only to find out what Shapland already knows, that he isn’t there. Could Shapland kindly get him to contact her? Cue a call from a Falanx colleague and one satisfied receptionist. Now Shapland has a guest pass and visitor badge and it’s looking good for the hacker.

Then the receptionist summons the on-site IT guy, who is sceptical, but ushers his visitor into an office of 20, sits him down at a terminal and asks how he can help. Shapland requests a cappuccino, hoping it will keep the guy out of his hair for long enough to get what he’s come for. No such luck – turns out there’s a cappuccino button on the office machine. Then the guy says: “You going to be alright on your own? I’ve got a meeting for the next hour and a half.” No problem, Shapland replies, thanks for your help!

“I’ve done about 200 of these physical intrusions. I know from experience that if you play the role, everything will probably be OK. There’s always one person on the inside who knows what you’re doing, and they’re your get-out-of-jail-free card if it goes wrong.”

He was carrying three hidden cameras: one in the arm of his glasses, one in a “hideously” patterned tie, and a third in a standard lid for a disposable coffee cup. Which gave him the ammunition he needed to report back at the end, once he’d managed to make off with the prize.

Some companies stop there, limiting themselves to reading the report and berating their employees. Others, chastened, will buy into Falanx’s full Managed Detection and Response (MDR) service, which involves 24-hour manned digital surveillance from their centre of defensive operations in Reading. “Imagine that a company is protected by anti-virus walls. There are always ways in. MDR is like the police patrolling inside those walls.” A ransomware attack is especially crippling. Not only do you have to pay vast sums to get your data back, but if you don’t pay up, there’s the added threat of it being released onto the internet. “We call it double extortion.” The criminals have already taken out your backup systems, and insurance just means “you’re covered, but more likely to be targeted”.

For a company to outsource cyber security requires trust. “That’s why we based our operations centre in the UK,” Shapland explains. “We want people to be able to say: I want to come and see you, physically see the guys looking after our data.” It’s digital with a human face, which is how I’m able to meet Rob under his real name. Many rival companies rely purely on AI, saying it guards against human error. “But then the onus is on you to manage that AI. You haven’t got someone doing it for you, like we do. That’s where the “managed” part comes in.” A human-AI alliance is the most powerful form of defence.

The most common response to one of Shapland’s intrusions is to get him in for staff training. Rather than simply tell people what they shouldn’t do – don’t let yourself be tailgated, don’t click on random links – he shows them what happens when they get it wrong. “They’ll see me walking into their building, they’ll see themselves in the video, and because they’re engaged they remember it. I do a lot of training, but always through stories. I tell a story and weave in the advice as I go.”

Rob was into team sports as a boy. He still runs and does obstacle-course racing, and plays strategy games like Agricola. What he wasn’t into was drama. “I suffered a lot from anxiety. I couldn’t have imagined doing what I do now and going on television and talking about cyber security. I was the one in the back trying to keep myself to myself.” That’s why he was attracted to red team hacking in the first place. “I wanted to push myself out of my comfort zone.” Having to inhabit another persona spoke to his creativity and took him out of his own head. He had a gift for the job, and felt empowered to do good in the world, to help in the fight against evil.

Which brings us to Russia’s war in Ukraine. Just the day before, Joe Biden had warned of the increased likelihood of cyber attacks against the West in retaliation for sanctions. An attack on national infrastructure is considered relatively unlikely, because such things as water, electricity and gas are backed up by highly resilient systems that take mere hours to kick in. The financial industry is likewise well defended. What Shapland predicts is that Russia will scan the internet for vulnerable SMEs using out-of-date software, with a view to disabling thousands at a single stroke. “With one action you can take out ten thousand companies. Then automatically deploy the ransomware and encrypt their entire networks. If you’re not interested in money but just want to disrupt, then mass-scanning and mass-attacking everybody is the way to go. Imagine trying to operate a business with no idea who your customers are.”

What should companies do to protect themselves? “Get their systems patched and up to date, introduce multi-factor identification systems, and invest in MDR.” It sounds like a lot, but Falanx Cyber expects to get the basics in place within hours, or at most a few days.

“One hundred percent the reason I got over my anxiety was because of work,” Shapland concludes. “Because of needing to break into buildings.” It’s not your run-of-the-mill therapy. But it sure sounds like fun.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments