How Memory Lane Games are trying to help those with dementia

Bruce Elliott and Peter Quayle tell Heather Martin about how they came up with an app game to help families struggling with dementia

I know, let’s call it Dementia Day,” Quayle said to Elliott. Or maybe it was the other way around. But when Elliott mentioned it to his 88-year-old mother back in Canada, she protested: “You think I’ve got dementia?” In the end, they called their digital health care app – winner of a KPMG “Tech Innovator” award – Memory Lane Games. Lucky Elliott’s mum was still watching out for him.

Mrs Elliott was “sharp as a tack.” But it was a different story for 90-year-old Mrs Quayle. She’d seen off cancer and was “built of the good stuff, with a heart function better than me”, her son says, but her memory had been going for a while. “I’m a computer scientist, no medical training; you do your best, chat about things, look for common threads – we can talk about the cats we had when we were young, even though she’s forgotten what was on TV today, or what she had to eat.”

By 2025, it is predicted that more than 1 million people in the UK will have dementia, with experts warning that cases will triple across the world by 2050. Families are taking on ever greater caring responsibilities. There are currently no prescriptions without side effects.

Good mates Bruce Elliott and Peter Quayle were sitting in their local on the Isle of Man, comparing notes over a pint, when they realised their mothers shared a love of old family photos. Bruce thought: I wonder if we can turn those photos into games? “That was the start of the journey.” Despite plenty of research into early detection, and delaying onset, there was “not enough innovation post diagnosis”.

Peter mocked up a game with pictures of his mum’s wedding: it was essentially, what year did you get married and who’s that standing next to you? Then they built another on Vancouver, for Bruce’s mum to test. They hired a young engineer “who knew about ten programming languages” as chief technical officer, and together made “some really good choices” to use tools from Google and Facebook and Mongo to keep development and infrastructure costs low. The engineer graduated with a first in mechatronic engineering from Lancaster University and now acts as an advisor, but “he built us a system that was incredibly scaleable and ran for free. Last month we had 10,000 people using our app,” Elliott says, “and our tech stack cost was zero.”

Peter, “a back office guy who looks at patterns”, was born and bred on the Isle of Man like his mother before him, and Bruce, a businessman with a background in gaming and marketing, came from Canada 19 years ago; their daughters met on the first day of school. “It’s the most wonderful place to raise kids,” Bruce says. “They’re taking the bus all over the island at 10 years old.” Peter’s mother is in a care home, a “fantastic place, like a hotel”, but he lives just five minutes away and can see her every other day. The government is equally accessible. Peter describes how they could pop in and see the chief minister at a couple of days’ notice, how the place is moving away from off-shore finance and rebranding itself as “the digital isle”.

We’re a much smaller company; we’re going to raise £5m, and with that we can keep our independence, we can keep our commitment to our free app all over the world

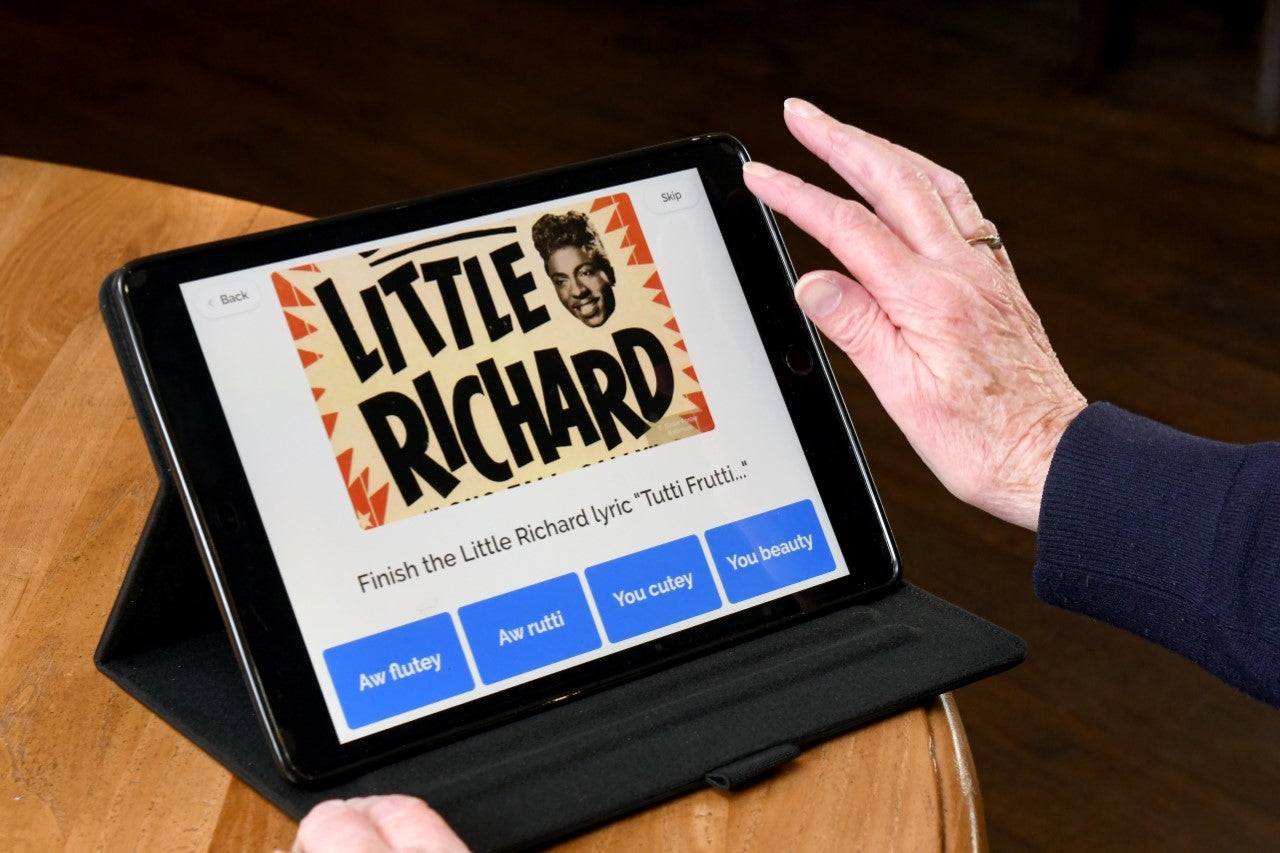

The games are mobile-based and built to a “frustration-free design”, with large buttons for answers: if you get the answer wrong “it just disappears as if it was never there”. There are around 1,500 games available, all for free in 100 different countries, and all conceived to start “positive conversations between people with dementia and their carers”. Among the most popular is “Finish the Lyrics”, organised by decade and tailored by country. Bruce recalls visiting a memory café in Birmingham, and how one old guy grabbed a tablet and started playing, his carer watching. Suddenly the guy stops and says, “Roy Orbison was way better than Elvis,” before breaking into a Big O song. His carer was in tears: she’d been looking after him for three months and he was usually non-verbal. There’s no scoring: it’s “all about the conversations that come from playing”. “You don’t say, ‘Hi Dad [cue: hello, but who are you],’ you say, ‘I wonder what this is,’ and start looking at this Beatles picture, and all of a sudden you’re engaged, and you’re talking.”

Memory Lane Games employs around 20 people, with offices on the Isle of Man and in Manchester. But Bruce and Peter’s children have built games for them too, and are representative of a growing pool of global volunteers. In the early phases of development, the company sought feedback from member countries of Alzheimer’s Disease International, which is how they come to have 250 games based on the Philippines, most in English but many also in Tagalog. “The Alzheimer’s Disease Association of the Philippines helped us localise content for the Philippine community, and are now prescribing our app for both stroke and dementia patients as cognitive exercise.” The app is also being used by speech and language therapists in the US. There are games on woodworking, cakes, cars and deciduous trees: “whatever the theme, we have volunteers building games for us”. Everyone has parents, everyone has interests and memories, everyone is qualified.

Elliott and Quayle are also teaming up with companies to support ESG (Environmental, Social and Corporate Governance) programmes demonstrating social impact. Staff are invited to pick a topic and provide six questions with multiple-choice answers; the Memory Lane Games team then curates the content, and sends a message to the volunteer saying: “congratulations, your game on classic motorcycles [for example] is now live.” Companies report that employees find the process therapeutic, and derive satisfaction from the sense of doing good. “What’s unique is how simple our games are,” Bruce says, “and how scaleable the product is globally. We can add a new game every day, on any topic from Perth gardens to beaches of Australia to piers across Britain. And we have minutes of game play, which is minutes of impact.”

Memory Lane Games is a seed stage start-up with plans to be profitable by Q3 of 2023. So far they have raised £1m, mostly from government grants and high-net-worth families; their immediate goal is £5m. “We can deliver free dementia care apps in every country in the world. But we need strong commercial models to support that activity.”

First among those models is a premium level, where for a few pounds a month families can personalise the app to create new games with their own photos, exclusive to them. Second are white labels, allowing healthcare organisations to build the app into their brand, likewise on subscription. Longer term, Elliott and Quayle are looking to join the “massive wave” of clinically validated prescription apps (Bruce cites bighealth.com‘s Sleepio, featuring a narcoleptic dog as a sleep aid, as an inspirational example), with Memory Lane Games set to become a prescription app in Germany next year. “The risk of digital health is much lower than traditional pharma, so governments are putting in new frameworks to accelerate the benefits of digital health in their populations.”

Hospice Isle of Man are undertaking a randomised clinical study of the app once a week for nine months involving 30 people with mild or moderate dementia, only the second clinical trial to be initiated on the island. “As we evolve to the point where our app is prescribed,” says Elliott, “we’ll have benefitted so much from the learning, the 50,000 downloads with people teaching us what works.”

According to Elliott, there are now many digital health unicorns raising significant capital. But he and Quayle are taking a different approach. “We’re a much smaller company; we’re going to raise £5m, and with that we can keep our independence, we can keep our commitment to our free app all over the world, and still fund this sustainable business. We’d rather impact a billion people than earn a billion dollars.”

The two men reminisce about a colleague who lost his mother to dementia, who had been playing a game on Manchester with her when suddenly she said: that’s the bench where I used to meet your dad when he came back from the war. “You hear memories you’ve never heard before. That’s the real magic: the conversation, the warmth of the moment. You break out of that six-minute loop of ‘why am I here and I want to go home’.”

“We fell in love with digital health,” Elliott says. “We built something that our mums loved and now it’s loved all over the world.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks