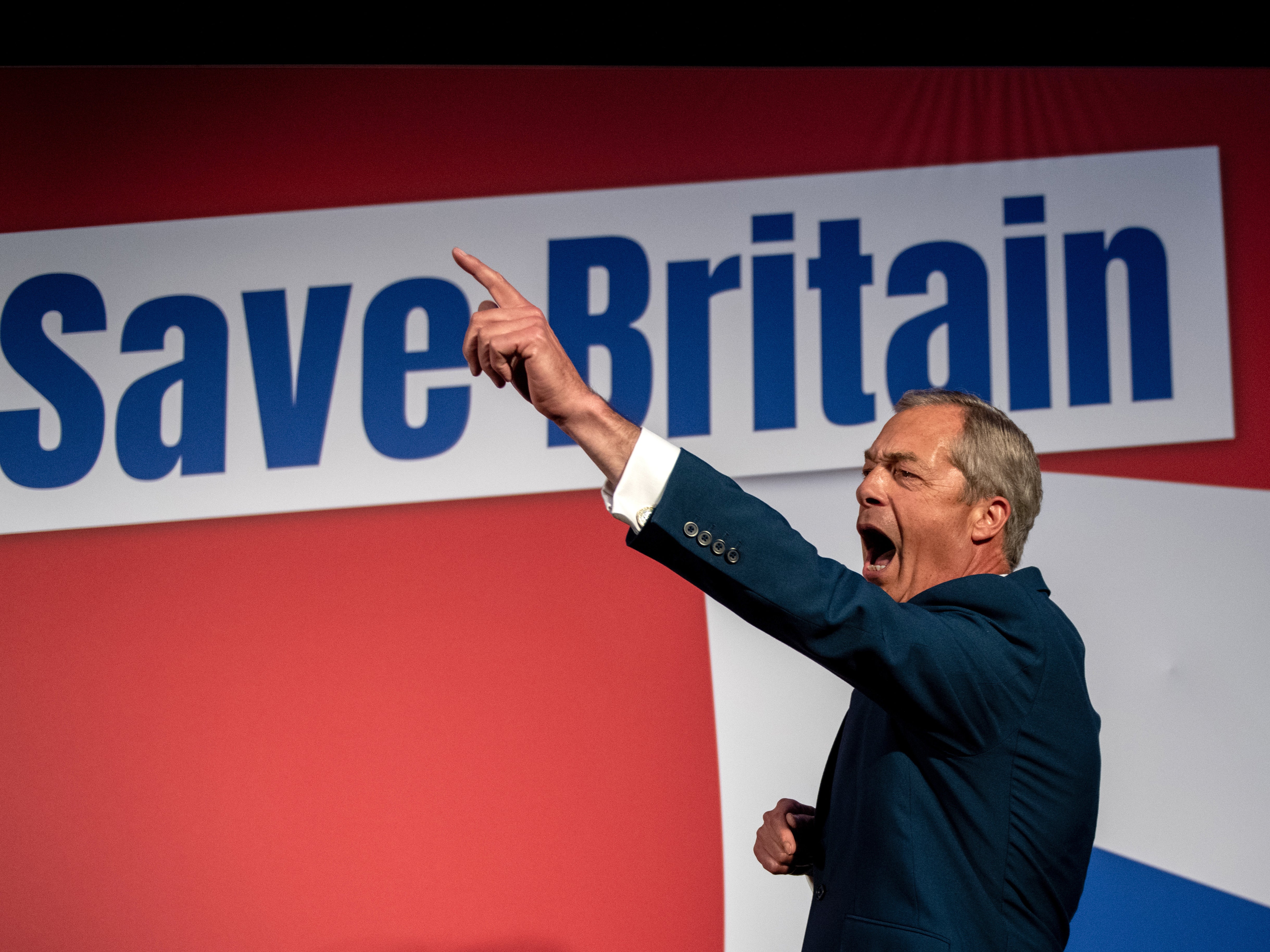

Why Nigel Farage’s immigration plan would be bad news for the economy

All the parties are promising curbs on immigration but the Reform leader has gone even further, saying he wants to cut net migration to zero. What would this do to the British economy? James Moore reports

Could Britain cope with Nigel Farage’s “net zero” migration without an economic meltdown? Privately, employers are running scared, not just of Farage but of the promises made by Labour and the Tories, both desperate to neutralise the threat posed by the Reform Party leader.

They are well aware that Britain needs migrant workers to cope with the labour shortages that bedevil its economy.

Official figures show that the number of job vacancies in the UK outstripped the number of unemployed people available to fill them as recently as the summer of 2022. An improving economy could easily deliver a repeat of that. UK business relies on immigration to keep the wheels of commerce turning. But by how much?

Madeleine Sumption, director of the Migration Observatory at the University of Oxford, says it is hard to quantify the costs and benefits because “different types of immigration have very different economic impacts, and the economic impact isn’t always the decisive factor when making policy decisions”.

“Ukrainian refugees are not expected to have a net positive impact and that is not why they were admitted,” she says. “For some categories, like work visas, the economic impacts are the main consideration. One of the challenges here is that there is no single metric to help policymakers decide which workers to admit.”

However, she adds: “Given the recent increases in salary thresholds in the private sector to £38,700 [for visas], the large majority of private-sector workers would now be expected to make a net positive contribution to public finances, for example. This implies that further restrictions beyond this point would likely have a negative fiscal impact.”

Immigration also has an outsized impact on certain important economic sectors. Take hospitality. Trade body UK Hospitality is keen to stress that 75 per cent of the industry’s workers hail from the UK. But that means 25 per cent come from overseas. In London, that number is much higher.

Will MPs be as keen to talk about migration curbs if there are no baristas to serve them their coffee? Or pull pints in the House of Commons’ many (taxpayer) subsidised bars?

Kate Nicholls, the boss of UK Hospitality, says: “While we recognise the need to control migration, this debate cannot be arbitrary and divorced from economic reality. There needs to be a serious debate about a pragmatic and stable employment plan that balances investment in skills and training, including reform of the apprenticeship levy, with sensible access to work visas.”

Construction is another industry that has had to call upon overseas workers to cope with labour and skills shortages, which have been made worse by an ageing British workforce and EU staff returning home.

“Putting arbitrary limits on skilled immigration on key roles before a plan for upskilling beds in could stifle economic growth. To that end it is unhelpful to take a broad brush approach to migrant workers given the way it impacts a number of sectors,” says Liz Drummond from the Construction Industry Council.

These are the uncomfortable realities policymakers beating the anti-immigration drum will face if and when they take power.

The latest migration figures show that net migration – the difference between the numbers of people arriving in the UK and those leaving – stood at 685,000 in the year to December 2023. That was a 10 per cent fall on the same figures the year before, but are still at historically high levels.

At the last election, net migration was around a third of current levels – and the Tories pledged they would cut it from that number.

In this campaign, both Labour and the Conservatives have said they want to bring down migration but neither has committed to a figure. Only Farage has said he wants net migration to be brought down to zero, with the number of visas for new arrivals affected by the numbers choosing to leave the country.

Matthew Percival, future of work and skills director at the CBI, says it is time for “a more honest conversation about immigration”, recognising that demand for immigrant labour is a symptom of shortages.

“Further restricting visas won’t deliver growth or public services,” he says. “Demand for immigration can be reduced by investment in technology, innovation and skills, and by action to help more people return to work. Businesses want to see all parties at this election put forward credible plans to ease labour shortages and support growth, starting with how they will boost public and private investment.”

Where should those plans focus, bearing in mind that most of the main parties agree that the UK desperately needs economic growth and that labour shortages (as Fell says) will only impede it.

While we recognise the need to control migration, this debate cannot be arbitrary and divorced from economic reality

One way of reducing the demand for overseas labour would be to improve the productivity of the existing workforce. In terms of the G7 group of the world’s biggest economies, UK plc is ranked in the middle of the productivity pack, behind the US, Germany and France but ahead of Italy, Canada and Japan.

In 2022 the average UK worker produced roughly 16 per cent less per hour than their German or American peers. So there is clearly room for improvement. However, there are no indications of that changing anytime soon. A House of Commons briefing paper published last month warned that productivity growth has slowed from its 2 per cent trend level in recent years.

Changing this would require heavy investment in skills and training, which all the business leaders I spoke to (including the many who felt immigration was too much of a hot potato for them to touch) would support.

Telecoms billionaire John Caudwell, formerly a big donor to the Conservatives under Boris Johnson, blasted the Tories’ record on investment in a recent Financial Times interview while calling on Labour to be “bold” when it came to investment. The party will need to be, if Keir Starmer is to realise his stated ambition to reduce immigration without damaging the economy.

Another way to reduce labour shortages would be to better utilise the domestic labour force and get more people classed as “economically inactive” into work. Data from the Office for National Statistics shows that economic inactivity is running at record levels. Those tarred with this unflattering designation include students, carers, retired people and those incapacitated through health conditions and/or disabilities (also running at record levels).

Prime minister Rishi Sunak recently railed against what he called Britain’s “sick note culture”, even though UK rates of absence are actually lower than in the US or Germany. His ally Mel Stride, at the Department for Work and Pensions, has sought to expand the “fit note” programme and says he wants to see more disabled people working.

The trouble is, says disability charity Scope, the labour market is not a friendly place for them. Director of strategy James Taylor says disabled people often face exclusion from the workplace. Employers are often to blame.

“The most common reasons include employer attitudes, lack of flexibility and inadequate support. As a result, the disability employment gap has stubbornly remained at around 30 percentage points for over a decade,” he says.

He also criticised the current welfare system for “forcing disabled people who are too unwell to work into unsuitable jobs by threatening to cut their benefits”.

Tony Wilson, director at the Institute for Employment Studies, also criticised the coercive approach and described the labour market as “ailing” in a recent blog post. He urged government to “build a system that is focused on helping more people find better work, on what you can do not what you must do, and on building meaningful partnerships.”

But there is little sign of that at present. Even if it changes, and Britain suddenly enjoys a leap in productivity, the need for some level of immigration will remain, particularly in sectors such as the NHS and social care.

However willing, disabled people aren’t going to be suitable to work as carers. They are more likely to need them. Nor are people who have taken early retirement likely to be keen to take up this sort of work. NHS workers, meanwhile, require extensive training.

It is worth noting that when Mishal Husain put Farage under pressure in a BBC interview – something few broadcasters have been willing or able to do – the net zero target wobbled a bit.

But Farage’s presence means Labour and the Tories are likely to have to continue to talk about the issue, probably without any reference to the economic impacts of any promises they make.

Unfortunately, as Unison’s general secretary Christina McAnea has said: “Until there are sufficient homegrown health and care workers, who are paid enough to keep them in their jobs, the UK is reliant on the overseas staff who choose to come here. Any slowdown is bad news.”

An incoming government of whatever stripe will have to deal with that hard reality once the rhetoric of the general election campaign is over.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks