Book of a Lifetime: ‘Pedro Páramo’ by Juan Rulfo

From ‘The Independent’ archive: Suhayl Saadi on ‘Pedro Páramo’ by Juan Rulfo

For me, reading Pedro Páramo is like opening a small mosaïque box, only to discover that it is empty, save for the whispers of those who had opened the box in the past. The novel is set in the post-revolutionary dustbowls of early 20th-century Mexico, when rapid industrialisation left hundreds of ghost villages scattered across the rural south. Urged by his dying mother to reclaim his patrimony, Juan Preciado arrives at Comala, and finds that things are not as they seem.

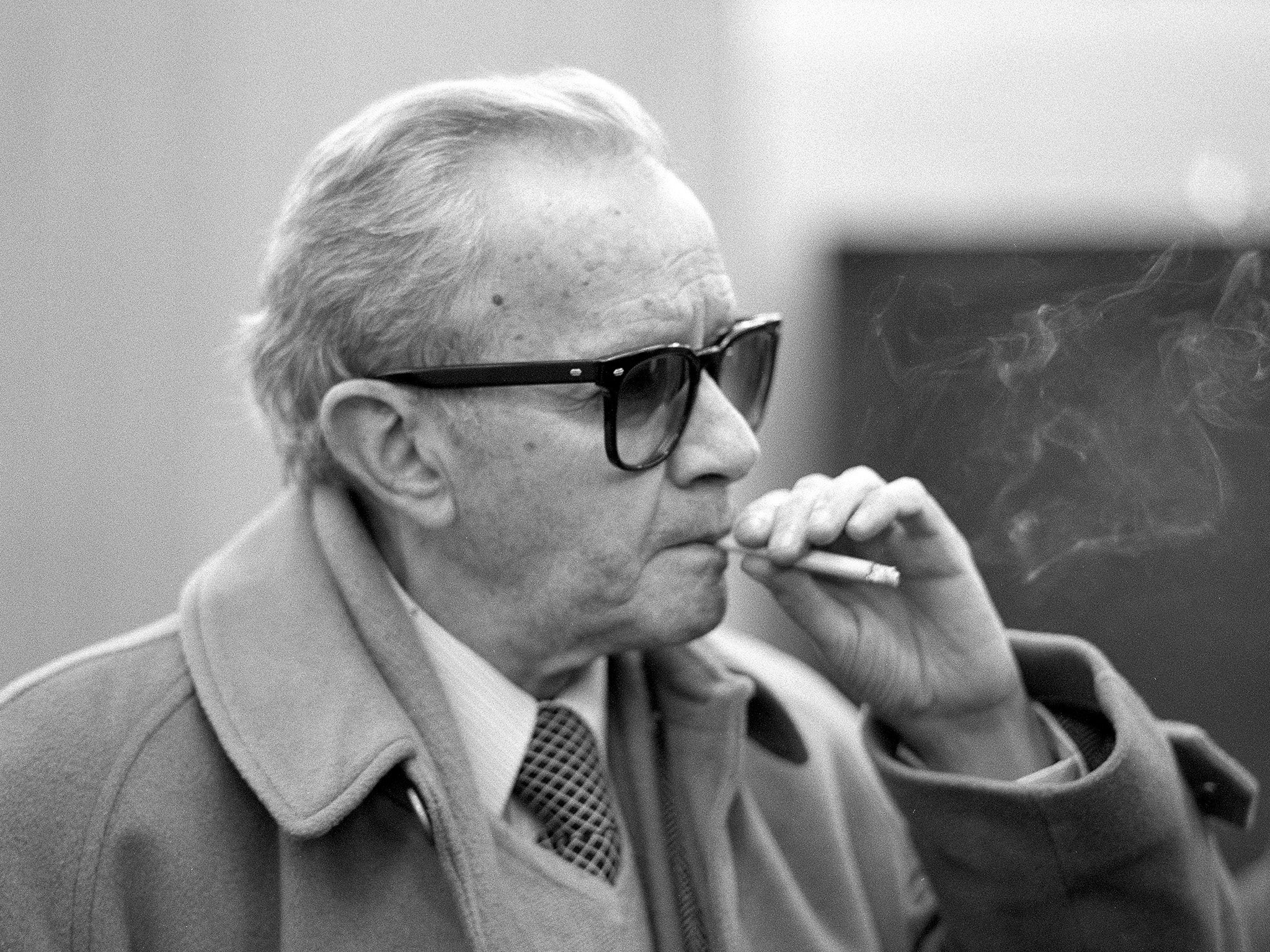

Written by immigration agent Juan Rulfo with state funding and published in Mexico in 1955, this psychotic novel does everything one could never dream of if limited by contemporary creative-writing dogma. The book’s structure fragments and its protagonist fades out of the narrative, there is no clear plot-line, no hooks, no character development arcs, no climax, no epilogue, and one is left with an existential sense of dislocation and uncertainty.

If this novel were to have been written today, there is little possibility that it would have been published. Yet without Pedro Páramo (translated into English by Margaret Sayers Peden), there would not have been One Hundred Years of Solitude, Hopscotch or Midnight’s Children. The literature of the past 50 years, our conception of the relationship between the word and reality, would have been measurably poorer.

Redolent of the hallucinatory work of Poe, Lovecraft, Bulgakov, Laxness, Burroughs and perhaps Faulkner, this fluid, Dantean “Mexican Gothic” tale is part socio-historical commentary, part transformative song. Rulfo’s immigration job took him all over southern Mexico. He was an excellent photographer and later he became publishing director of the National Indigenist Institute. His is a text in which meaning is subsumed into an architecture of shadows and whispers, and into the ebb and flow of the vernacular. The prose is spare, vivid, luminous and yet evokes a pernicious sense of gloom.

While his iconic novel draws on booze, folk Catholicism and the peculiar Mexican relationship with death, unlike more fêted Latin American writers, Rulfo does not dance exotic. Although now central to literary education in Spanish, with a protagonist acknowledged as the oneiric descendant of Don Quixote, this slim novel remains comparatively obscure in the English-speaking world.

In the end, we all are trapped in the box. Yet the walls are porous, the self indeterminate. Great art – and Borges considered Pedro Páramo to be one of the greatest texts in any language – ultimately remains elusive, and allows us to catch murmurs of the absolute.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments