What is biohacking – and can you actually hack your health?

Biohacking is a divisive term, but it’s worked for Emilie Lavinia, and many others

If someone told you there were a way to “hack” your biology so you’d never get sick again, that you could hit pause on the ageing process and have boundless energy, would you believe them? It’s certainly an attractive prospect but given what we know about the inevitability of growing older, of succumbing to illness and degeneration and the taxing nature of our modern lifestyles, for most, the notion of “hacking” one’s biology lies somewhere between science fiction and snake oil.

Biohacking is a DIY approach to achieving optimal health. The idea is that by testing and tracking your body’s personal metrics and adapting your behaviours, you can improve your physical and mental health and athletic performance, stabilise your hormones and slow the ageing process. The practices many people employ to achieve these goals range from dietary interventions and supplementation to daily ice baths and injecting nutrients directly into the body. Within the biohacking sphere, you’ll find protocols that mix functional medicine and ancient practices with modern data tracking and genetic analysis. In short, there’s a lot going on here.

I’m suspicious of “hacks” in general. I’ve lost too much time to online videos that promise a “five-minute hack” and ultimately suggest a far more long-winded and counterintuitive way of doing a mundane task. Life hacks have never served me well so when I first heard about health hacks I responded with a natural degree of scepticism.

But the idea of hacking the human body, or “biohacking” is now a viral concept, with a strong church of committed disciples. Some practices seem fringe and radical – what normal person is really going to spend £2m a year on their diet and inject themselves with their own child’s blood in a bid to cheat death, à la Bryan Johnson – the biohacker at the centre of Netflix documentary Don’t Die.

Some forms of biohacking aren’t exactly cheap or accessible and attract a very well-heeled crowd. In fact at a recent and very exclusive Don’t Die dinner, Kim Kardashian shared her desire to live forever with Johnson as they shared biohacking tips with fellow longevity expert and enthusiast Andrew Huberman.

However, outside of moneyed celebrity circles seeking to buy back youth, other biohacks enshrine simple behaviours and modifications that modern research seems to support. However, it takes a lot of wading through data and personal trial and error to figure out how and why something might work, and for every biohacking breakthrough based on a scientific paper or personal experience, there’s an expert warning against cherry-picking data and overdoing it on supplements.

“Biohacking can often be another way of propagating wellness fads that don’t have scientific evidence,” says Professor Tim Spector, co-founder of Zoe and the author of Spoon Fed. “Respecting and understanding our biology and how to maintain our health, rooted in a robust understanding of human physiology and the scientific evidence, is the way I recommend focusing on improving our wellbeing. The idea that you can ‘hack’ your biology is another way of searching for silver bullets,” he says.

“It’s not something that I think is necessary for most people. Our bodies are clever and have evolved to help us to stay healthy. All we have to do is look after ourselves and eat foods to support our biology. For example, eating lots of different plants to support our gut microbiome will help us to feel better now, and live longer and healthier years.”

Read more: What happened when I tried a traditional Russian wellness ritual loved by biohackers

In my quest to understand the fundamentals of biohacking, I’ve interviewed hundreds of people, some with medical degrees, some self-appointed research enthusiasts, founders, athletes and chronically ill people who’ve turned their health around. While many of their stories and insights have impressed me and have appeared to rely on the basic tenets of good health that we should all be following, others have just seemed bonkers.

I recently spoke with a doctor about the benefits of self-injecting NAD (something the biohacking crowd is currently mad for), but I mentally checked out when my interviewee went off piste and started telling me about how he followed a carnivore diet and had never felt better. No one will ever convince me that only consuming large amounts of (often raw) meat and no fruits or vegetables is good for a human being, not even a doctor.

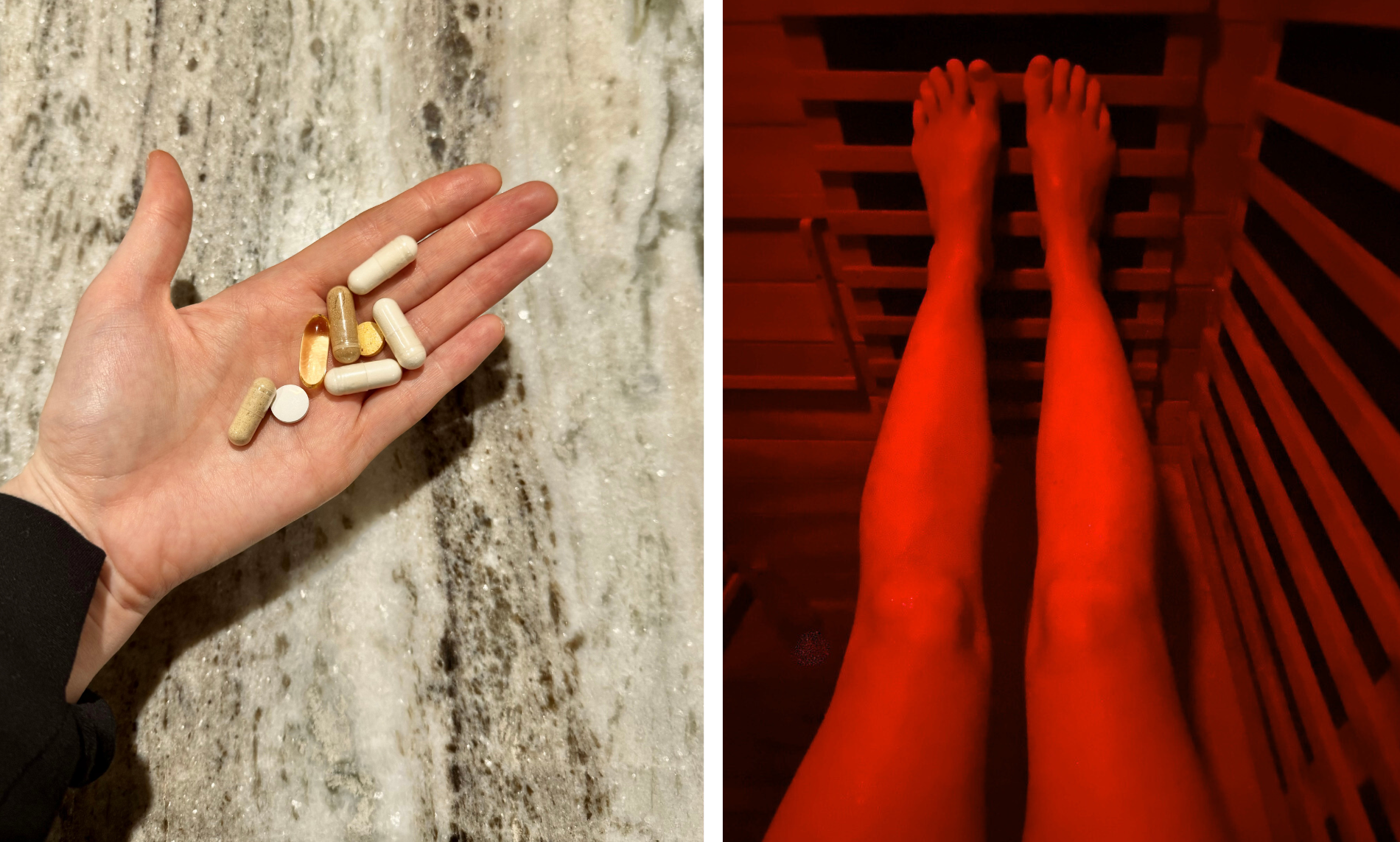

I began my own biohacking journey in 2020 in an attempt to discern what was going on with my hormones. I outsourced numerous blood tests to private healthcare companies, adapted my diet, started lifting weights, had my body scanned, took personalised supplements, tracked every available biometric using my Oura ring and spent a lot of time in infrared saunas.

I now know a staggering amount about my own body that I didn’t know before, including my biological age, which foods don’t agree with me and why I often feel so tired. I never set out to become a superhuman or live forever, but my body is the healthiest it’s ever been. Whether or not you’d call this process “biohacking” or simply taking an interest in your own body and embracing healthier habits is up to you.

Biohacking is a somewhat divisive term, but there’s definitely something in it, because many people, myself included, are seeing results.

How to practise biohacking

The starting point for most people with biohacking is diet. “There are a few types of ‘biohacking’ changes which have good evidence behind them,” explains Professor Spector, “one of these is ‘time-restricted eating’ or intermittent fasting. Zoe research shows that, on average, when participants switched to eating within a 10-hour window, they experienced improved mood and energy. More than half of them also reported improvements in gut symptoms, like bloating.”

Dave Asprey, an author and influencer who’s earned himself the moniker “the father of biohacking” famously used diet and fasting to turn his own health around, swapping a vegan diet for his own creation: The Bulletproof Diet. It is a protocol that supposedly supports weight loss, improved energy and cognitive function. It’s wildly popular and offers guidance on nutrition and intermittent fasting that most people can follow, but Asprey himself has said there’s no such thing as a one-size-fits-all approach.

Biohackers essentially rely on a set of golden rules for optimal health: eat well, get enough quality sleep, address nutrient deficiencies and move your body. But the real work begins atop these foundations and that’s where tracking comes in. Biohackers use fitness trackers like the Whoop, Oura or Garmin devices to gain a real insight into where the body is doing well and where there’s room for improvement. Other biometric tests also provide the data that’s needed to create a personalised protocol, like blood tests to assess hormone levels and genetic testing to check for the likelihood of high cholesterol for example.

Read more: Five reasons why you should be walking 10,000 steps every day

Tracking is central to being able to interpret your body’s needs and introduce the changes or “biohacks” that will foster optimal health. Professor Spector, who prefers the term “bio-harmonising” to biohacking, co-created the Zoe device, a continuous glucose monitor worn on the upper arm, to help people track their diets and improve their overall health.

“We all respond to foods differently, and knowing the best types of food, and how to eat them, can set you up for a lifetime of great health,” explains Spector. “The Zoe tests, which measure blood sugar control, blood fat control and gut microbiome health, among other metrics, help us provide actionable advice and guidance for members to make the smartest food choices – fuelling their bodies with the food that helps them thrive the most. For example, for one Zoe member that might mean starting their day with a savoury breakfast to help keep their blood glucose levels stable, or practising ‘food sequencing’, which might mean eating a sweet treat after a high-fibre, plant-based meal.”

Personalised testing is really at the forefront of biohacking. But knowing what you should test and how you should test for it can be tricky. Is a wearable like the Whoop enough? Or should you also be having regular blood tests and using a continuous glucose monitor? I currently measure my VO2 max, my heart rate variability, my basal body temperature, my glucose levels, my metabolic function and countless other metrics.

However, the newfound obsession with testing for the sake of testing is one of the reasons the biohacking movement has received criticism over the past few years. After all, if we feel relatively healthy, do we really need to test every possible indicator of our health to ensure we’re optimal?

Who can benefit from biohacking?

Like myself, I’ve seen many people turn to biohacking in a bid to take control of their health. Issues like anxiety, fatigue, weight gain, insomnia and chronic pain have led countless people down the path of tracking and attempting to optimise their wellbeing. For these people, health hacks aren’t about living forever, they’re about finding a comfortable baseline right now and learning about preventative measures that can be self-imposed.

Dr Samantha Decombel, the co-founder and chief scientific officer of FitnessGenes, a company that provides personalised fitness and diet recommendations based on DNA analysis, explains that “it can be quite frustrating when you see companies selling magic bullet solutions. Because ultimately, many issues are causative, the vast majority are more by association and probabilistic. But human biology is so complex and there’s so much going on that there could be other factors within both your genetic background or your environment that are having a much greater effect.”

“There are a lot of companies that are promoting longevity, living forever. You know this sort of narrative – that of perfection and being optimal. And actually, that’s not how biology works. Biology works on a system of trade-offs. So it’s about thinking, what’s the biggest risk to me? And what are the mitigations I can take to try and stave off that sort of chronic illness, as long as possible?”

Decombel’s approach to biohacking, much like Spector’s, is more about equipping people with the knowledge they need about their own bodies to make informed choices about their health than prescribing one-off hacks. And this is where biohacking can really work – when you understand specifically what your body is lacking and how to tip the scale to achieve a healthy balance, the outcome can be significant.

“We had one user,” explains Decombel, “who’d been out of work for two years because she had brain fog, and she’d really struggled with that. We identified a gene variant and she was able to start taking a supplement to address a deficiency. She said it was like the fog lifted overnight. But it was that one little bit of information and trying that one different intervention that meant she could work again. But everybody’s different, everyone is unique. For some people, they might learn how to eat a little healthier for their body genetically, but for others, testing can genuinely be transformative.”

The only drawback to all this of course is cost. Biohacking has a reputation for being popular with millionaires with limitless resources. Not everyone can afford regular personalised testing, expensive supplements and a full-sized ice bath in their back garden. Even fitness trackers are still not ubiquitous enough to offer competitive pricing.

“That biohacking space is very dominated by an elite few that have the time and the resources to invest in it,” says Decombel. “And [genetic testing] is something that actually is relatively cheap and it could be made available a lot more widely.”

The basis of all biohacking is taking the right steps to feel better and whether these steps are complex and expensive depends on your goals. There are plenty of free biohacks that self-optimisation influencers, such as the likes of neuroscientist Andrew Huberman and Health Optimisation Summit founder Tim Gray, recommend. Things like getting morning sunlight, having a consistent bedtime, hydrating before caffeine and doing daily yoga and meditation are all inexpensive biohacks that anyone can do.

Is biohacking safe?

There’s certainly no one-size-fits-all approach when it comes to your health, which is why experts have been so critical of the term “hack”. You might think that by plunging into an ice bath each morning, fasting for extended periods of time, lifting weights and taking supplements, you’ll be doing your body a favour. However, if you haven’t tested to see if you’re actually deficient in any of the supplements you’re taking, your body will have to work harder to process those excess nutrients. If you fast and exercise but don’t have enough energy, you could place your body in a state of shock and cause hormone dysregulation and fatigue. So while certain behaviours might work for some, not every biohacking trend will be safe or right for you.

It’s also worth noting that much of the scientific research that biohackers rely on to justify certain protocols has been conducted on male bodies, and further research is needed to confirm whether these protocols could be right for everyone. Researchers like Dr Stacy Sims posit that “women are not small men” and that personalised testing is vital if you want to enhance your health and performance. My own experience of trying out “bio bro” protocols that include fasting, 5am wake-up times and cold plunges have taught me as much.

Striking the balance between testing, tracking and trying new behaviours safely is where biohacking can work for you. As Spector says, our bodies have evolved to do a good job of keeping us alive and really, a lot of what biohacking focuses on is undoing environmental damage, not fixing a problem with our basic biology, which is already set up to function pretty well.

Cutting out foods and drinks that will likely upset your gut microbiome, doing regular exercise, getting enough rest and making sure you’re getting the vital nutrients you need are not so much biohacks as basic lifestyle changes that will help you in the long run. But if you want to start testing your hormones, checking how your deficiencies and genetic variants affect your health and adapting your behaviours in order to treat a health problem, consulting with professionals should be your first port of call.

Spector explains that “80 per cent of chronic diseases are caused by four modifiable factors: smoking, alcohol, diet and exercise”. Adding that there’s “no need to resort to extreme methods to ‘biohack’ our bodies if we’re looking after ourselves following the principles of a good lifestyle and diet. Our bodies are very smart, and they’re designed to keep us alive. So, if we learn to work with them and equip them well through diet and movement, then they’ll do the rest for us.”

Read more: I tried the viral 75 soft fitness challenge – here’s what I learnt

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks