Zoë Wanamaker: ‘Of course women should be the centre of attention’

At 71, the formidable star of stage and screen is still speaking out and taking parts that scare her. As she returns in Netflix fantasy drama Shadow and Bone, she talks to Isobel Lewis about her fight for better female roles and why she never cracked America

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Zoë Wanamaker was never going to be just another cookie-cutter star. “I knew when I was beginning that I wasn’t going to be a heroine,” she says. “In the classic sense – pretty, long legs, very thin, with big tits and stuff. It’s never been on the cards for me... I would like to have played Juliet. But nobody would ever cast me as Juliet, so fine. You can’t go backwards.”

Juliet or not, Wanamaker is one of the most beloved stars of stage and screen in the UK. The 71-year-old is a nine-time Olivier Award nominee for her work in London’s West End, and has also been up for Tonys for her appearances on Broadway, in shows such as Piaf, Loot, Electra and Awake and Sing! On screen, she’s probably best known for her role as matriarch Susan in the long-running BBC sitcom My Family and as Madame Hooch in Harry Potter and the Philosopher’s Stone, excelling, in particular, at playing formidable women.

The arts were always in Wanamaker’s blood: she was born in New York to Canadian actor Charlotte Holland and American actor and director Sam Wanamaker. Her parents were Jewish – although she tells me she identifies as “Jew-ish” – and despite her family moving to the UK when she was just three after her father was blacklisted in the US, she grew up with a decidedly American sense of humour – which is to say, just a little bit “naughty”.

Her whole life, Wanamaker has been surrounded by people fighting for what they believe in. Her father spent 27 years of his life lobbying for the building of the Globe Theatre, she recalls. “My dad said, ‘You know, the English are very slow. They can’t get excited about something. They have to do this and this... to move a tanker around to change them. It’s slow.’” When it was finally built in 1997, she was the first person to speak on its stage, in his honour.

Then there were the other young actors she worked alongside in the 1970s, who were “very forward” in discussing topics such as equal pay. “I was part of that generation who hopefully began to change things,” she says. It’s a cause she’s long advocated for, along with that of improving the roles available to women on screen. “I suppose an actor’s mission is to find things that are deeper than that, so that you’re not just the girlfriend, or the person who’s been run over by a truck, or a housewife. You’re more than that,” she says.

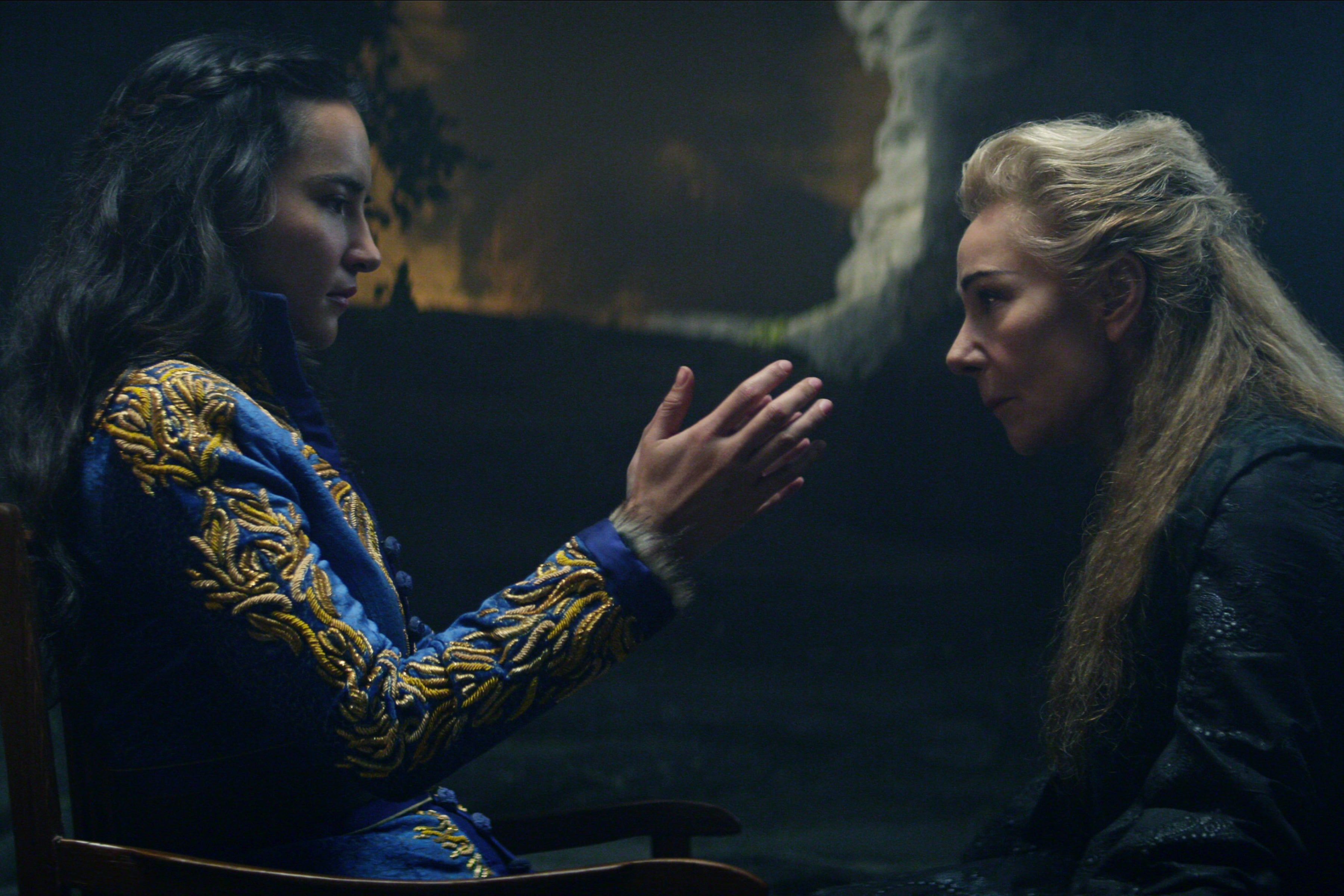

Now, Wanamaker seeks out projects based on how “intriguing” they are. This was a major factor in deciding to take on her latest role in Netflix’s big-budget fantasy series Shadow and Bone, based on Leigh Bardugo’s Grisha trilogy of young-adult novels. Set in the war-torn world of Ravka, the books centre around Alina Starkov (Jessie Mei Li), an orphaned soldier who learns that she has magical powers that make her capable of freeing her country from evil.

Wanamaker plays the role of Baghra (fondly nicknamed “Bag Lady” on the cast’s WhatsApp group), a wise and harsh teacher tasked with training Alina to harness her powers. She took the part for two key reasons: it was unlike anything she’d done before; and it was, in her words, “completely nuts”. While she’d never heard of Bardugo’s books before reading the script, she quickly became fascinated by their huge, young fanbase, whose reaction to the show’s announcement bordered on “hysterical”. “I looked it up online,” she says, “and I suddenly found this girl who was going” – she puts on a high-pitched American accent – “‘I’m so excited, Shadow and Bone has been cast! This is the best thing since Harry Potter!’ It’s tribal.”

Beyond the impressive special effects, gripping plot and stunning costumes, Shadow and Bone is notable for how female-centric it feels. Fantasy shows have often faced criticism for reducing women to secondary characters or sex objects, but it made total sense to Wanamaker that the show would be written by and told from a female perspective. “Women, of course, should be the centre of attention because we give birth, and we support, and nobody gives a monkey’s fart why,” she muses. “You have to make sure that – you know, as a woman, girl – that you’re not beneath [men]. You’re equal, if not better,” she adds with a delighted cackle.

This idea of standing up for what’s right and learning to say no has been woven through Wanamaker’s career. She worked on My Family for 120 episodes across 11 series from 2000 to 2011, but was vocally unimpressed with the quality of the writing following the departure of showrunner Fred Barron. In a 2007 interview with The Daily Telegraph, she claimed that she and Robert Lindsay had refused to film an episode because the script was “so bad”, adding: “That caused a lot of problems, but we just felt it was not good enough.” In the end, she tells me, it was “more of a loyalty to the actual piece” than belief in its quality that kept them on the show. “[My Family] was a learning curve for me,” she says – “that you can actually say, ‘This is not good.’”

I wonder aloud where that courage to speak out comes from, and Wanamaker recalls being fresh out of drama school, working in repertory theatre to get her Equity licence. There she learned to collaborate with her fellow actors, and that “if something’s not comfortable, you have to speak otherwise you’re not doing your work”.

There’s a casual defiance to Wanamaker that makes it hard to imagine a world in which anything could hold her back. But reminiscing about her 45-year career, she says choosing to stay and work in the UK rather than going to the US when she was young will always be a sticking point. Not a regret, per se, but something she wishes she’d been “more confident” about. “I was too English and way too sensitive to go and put myself out to America… That’s what I feel I’ve missed. My dad said to me once, ‘If you don’t put out, you don’t get out.’ I’ve always remembered that, because I’m not a pusher.”

Wanamaker is clearly indebted to theatre for the shape her career has taken and, like many in the industry, has struggled without it for a year. But things are (tentatively) beginning to look up. Just hours before we speak, it’s announced that she is going to star opposite Peter Capaldi in a new production of Nick Payne’s two-hander, Constellations, at the Vaudeville Theatre, with a rotating cast of actors including Russell Tovey, Omari Douglas and Anna Maxwell Martin.

She lights up when we discuss theatre’s return. “I think people will be thirsty again and that’s the most important thing,” says Wanamaker. “What concerns me is that because of Covid, we’ve left young people behind somewhat. And that’s because they’re isolated [by] this thing… so their imaginations, their own brains are being slightly squished.” Her hope, she says, is that the return of the arts will allow the industry to “claw back” the punters. “I’m hoping that they can’t be lost because it’s such an extraordinary thing that we have, the arts all together.”

The conversation turns to the government’s much-touted £1.57bn culture recovery fund, which has been sold on the promise of keeping the arts alive. While Wanamaker says she is “grateful” for the money being given to the arts, she’s keen to point out that much of the funding is in loan form that must be paid back. Brexit will make it more difficult for artists to tour across Europe, too – “it’s a clusterf***”, she says, adding that it’s reflective of a larger underappreciation of the arts.

“All I know is that Germany and France have a much bigger budget to support the arts – much bigger,” says Wanamaker. “And it’s part of the culture. Why is it not part of our culture, when we have so many extraordinary artists, architects, painters, writers, blah blah blah…? The sciences and the arts are the lifeblood of a country – without that we’re pallid. We have to keep that knowledge that we come from particular ancestry, and it should be passed on. It’s crippling if it’s not.”

It’s a bleak prophecy, but there’s optimism in Wanamaker’s words. After all, the stories being told across the stage and screen are more interesting, the opportunities for actors more diverse, and the industry is slowly becoming more inclusive. And on a more personal note, there’s no fear holding her back, says the actor. “If it scares me, then it’s worth doing.”

Shadow and Bone is released on Netflix on Friday 23 April

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments