The Sopranos at 20: Flawed anti-heroes are now everywhere on TV, but they all began with James Gandolfini’s mobster

This story of an anxiety-ridden mob boss, which premiered 20 years ago today, opened the floodgates for a new breed of TV protagonists, writes Gerard Gilbert

You can tell that The Sopranos is a fairly ancient TV show from its opening credits. Cigar-sucking “waste management consultant” Tony Soprano (James Gandolfini) drives away from New York City to his suburban mansion in New Jersey, to the menacing beat of Alabama 3’s “Woke Up This Morning”. And there they are, reflected in his wing mirror: the Twin Towers.

The World Trade Centre would have had no greater significance when this sequence first aired 20 years ago today, on 10 January 1999, than any other Manhattan landmark – the same Manhattan where characters from NBC’s sitcom Friends, then ruling the airwaves, supposedly hung out. But while Friends witnessed the last gasp of network dominance, The Sopranos, from cable upstart HBO, was the future of television. Or as the company’s famous slogan would prefer it: “It’s not TV, it’s HBO”.

It was The Sopranos that first gave credence to that boast. In the intervening two decades, much has been written about how this story of an overweight, anxiety-prone mobster and his internecine family would pave the way for today’s Netflix-led box-set culture; how American television – the “idiot box” traditionally driven by its fearful advertisers – was suddenly being compared to Dickens and Shakespeare.

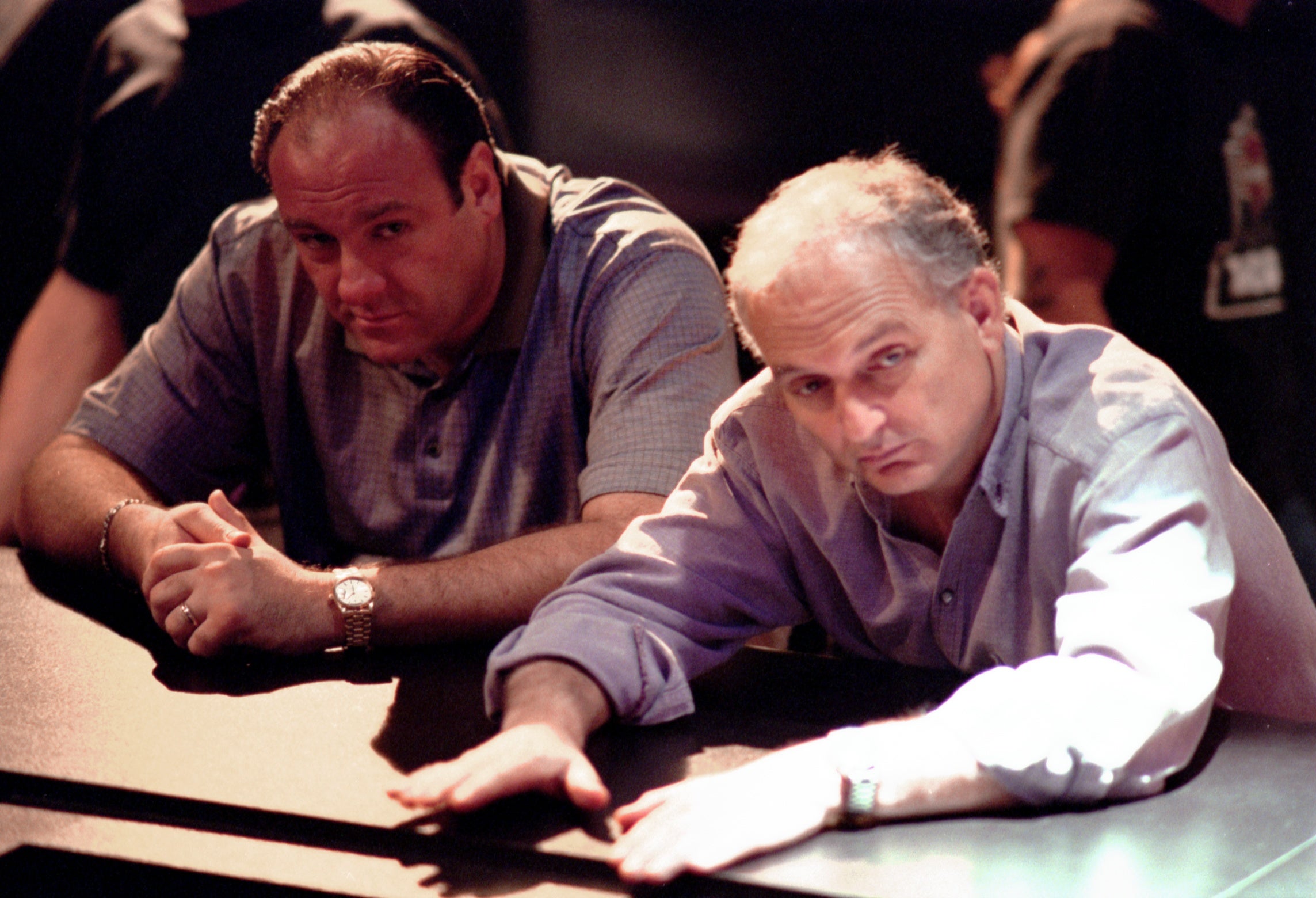

Before 1999, David Chase was a dissatisfied veteran of network TV, having written for The Rockford Files and Northern Exposure. The Sopranos was to be his baby.

By creating a show about Italian-American gangsters he was, of course, following in the considerable footsteps of Martin Scorsese. The Sopranos shared 27 actors with Scorsese’s 1990 movie Goodfellas, and Scorsese himself made a cameo appearance in only the second episode. But the show set itself apart too. While critics had begun to notice Scorsese’s “helpless yearning to get in on the act himself” – as David Thomson suggested in his book Have You Seen...? – The Sopranos offered a less romantic take on the mobster milieu. When we first meet him, Tony is having stress-related blackouts, causing him to seek the services of a therapist, Dr Jennifer Melfi (Goodfellas’ Lorraine Bracco) – the moral centre of the show.

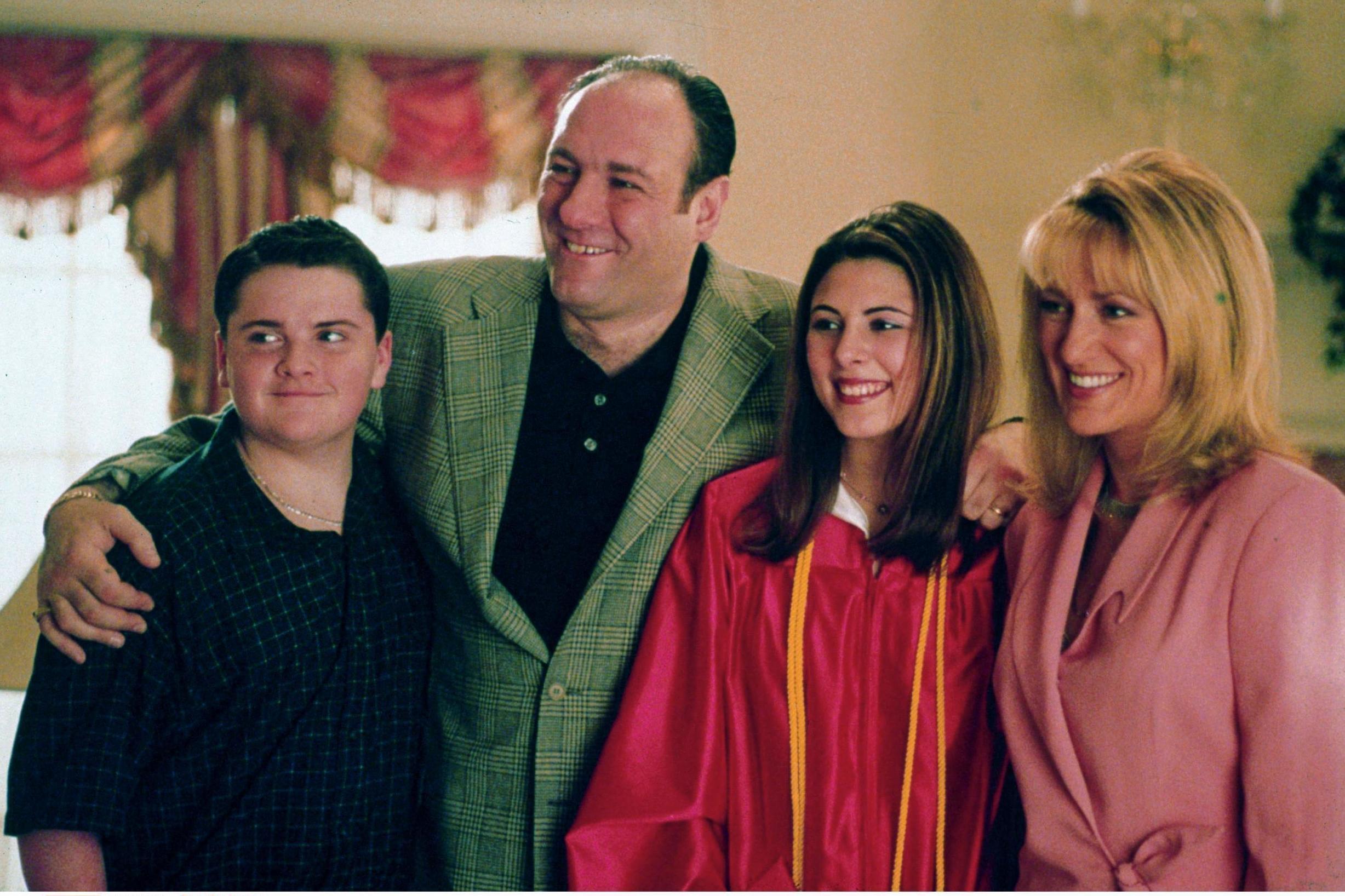

As Chris Albrecht, the then-head of original programing at HBO, put it: “I said to myself, this show is about a guy who’s turning 40. He’s inherited a business from his dad. he’s got an overbearing mom. Although he loves his wife, he’s had an affair. he’s got two teenage kids ... he’s anxious; he’s depressed; he’s searching for the meaning of his own life. I thought: the only difference between him and everybody I know is he’s the don of New Jersey”.

It’s a hell of a role for any middle-aged male actor, in other words, and James Gandolfini’s triumphant embodiment of this midlife crisis-driven thug was among the first to alert movie actors – then a caste (and several pay grades) above mere TV thespians – to where the rewarding work lay. These days it’s rare to find a film star who hasn’t dipped their toes in online original programming: Jane Fonda, Julia Roberts, Nicole Kidman, Sean Penn and Michael Douglas are just a few of the Hollywood deities taking the Netflix and Amazon dollar.

The Italian-American, New Jersey-raised Gandolfini came to the attention of casting director Susan Fitzgerald when she saw a clip of him playing a mob enforcer in the Quentin Tarantino-scripted True Romance – but Gandolfini did his best to sabotage his Sopranos audition.

“In the middle of this audition he says: ‘This is s***. I gotta stop’,” recalled Chase, shortly after the actor’s death from a heart attack in 2013 at the age of 51. “And he left the room, went down the street and disappeared. And so another audition was set up. Then we heard someone in his family had died – when, in fact, no one had died.” Chase now thinks that Gandolfini might have been bipolar. “Finally, he came to my house, in my garage, and auditioned there. He did great – like we knew he would – and after I got to know him, I realised this was standard operating procedure for him.”

Gandolfini’s erratic behaviour was legendary – the actor would sometimes go missing for days on end, requiring expensive schedule rejigs. Off camera, he would keep to Tony’s famous dressing gown, desperate to stay in character. This intense identification had a powerful effect. Critics have written of feeling a strange need to be in Tony’s good books. “I got the sense that he was watching me as I wrote,” admitted Australian author and journalist Clive James, who reviewed the show in 2004, “so I tried hard to get it right, while always trying to remind myself, of course, that he wasn’t really a gangster, just an actor.”

James thought The Sopranos superior to The Godfather movies, though his view was not shared by David Thomson, who felt that Tony was mundane compared with Michael Corleone. “Great art concerns people of true nobility who nurse a flaw,” opined Thompson. “Long before the end, I fear, both Tony and James Gandolfini were bores – characters of an innately supporting nature.”

In which case, Thomson must take a dim view of the countless flawed protagonists who have spewed out of television in The Sopranos’ wake, from The Wire’s Stringer Bell, Breaking Bad’s Walter White and Mad Men’s Don Draper to today’s glut of flawed anti-heroes in dramedies like Get Shorty or Barry, or drug sagas such as Narcos and Gomorrah. You name them. Nobility, flawed or otherwise, is in short supply these days in premium television drama.

“These were characters whom, conventional wisdom had once insisted, Americans would never allow into their living rooms: unhappy, morally compromised, complicated, deeply human,” says journalist Brett Martin in the introduction to his book Difficult Men: Behind the Scenes of a Creative Revolution. “They played a seductive game with the viewer, daring them to emotionally invest in, even root for, even love, a gamut of criminals.

“And it would no longer be safe to assume that everything on your favourite television show would turn out all right. The sudden death of regular characters, once unthinkable, became such a trope that it launched a kind of morbid parlour game, speculating on who would be next to go.”

It’s a trope that has been adopted by British TV dramatists – in particular, Jed Mercurio, who delights in killing off seemingly indispensable characters, whether on Line of Duty or Bodyguard.

Which brings me to perhaps The Sopranos greatest moment – its incredibly tense and audacious ending, when the screen cuts to black, and viewers are left not knowing whether Tony and his family continued to eat their meal in the diner or whether they were wiped out by rival New York mobsters.

This controversial ambiguity was a statement of intent more than anything that had preceded it: television was never again going to play by the old rules.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks