You're so cool: True Romance is Quentin Tarantino's masterpiece... precisely because he didn't direct it

Twenty-five years on from reaching cinemas, Tony Scott's full-throttle direction is clearly the perfect foil for the 'Pulp Fiction' man's surprising script about two lovers on the lam

Early in 1993, in the same Los Angeles hotel where Bobby Kennedy had been shot dead 25 years previously, Tony Scott slapped Patricia Arquette across the face.

The director raised his hand not out of anger or cruelty, he would later explain, but to uncork a flow of emotion in his actor, who was having difficulty with the scene they were filming at the recently shuttered Ambassador Hotel on Wiltshire Boulevard (finally demolished in 2006). She was being violently interrogated by a mobster played by future Tony Soprano James Gandolfini (who’d rented a room in a fleapit motel and gone days without showering to prepare for the part). The script called for her to flit between several emotions: shock, terror, a violent desire for vengeance.

“My mind wasn’t where I wanted to be,” she would recall. “So Tony said, “Do you want me to help you?” I said yes, and he smacked me in the face. I was shocked. I started crying.”

It’s hard to imagine Scott, who died by suicide in 2012, getting away with such a provocation today. Then, there is a lot about True Romance – directed by the Top Gun filmmaker from a script by Quentin Tarantino – you couldn’t get away with today. As the film marks its 25th anniversary on 10 September, its manic energy and nose-thumbing at political correctness have never felt more like cast-offs from another era.

Consider the celebrated “Sicilian” scene: a jab-a-minute square-off between a top-of-their-games Christopher Walken and Dennis Hopper in which two white men deploy the “n-word” with glee. Elsewhere, future Oscar winner Gary Oldman plays a white rasta pimp. And Arquette’s character, Alabama, is a gooey prostitute with a heart of unsmelted gold – an empty vessel without agency and full of nothing but good intentions.

On its quarter century, the case can also be made that True Romance stands uniquely apart in the pantheon of Quentin Tarantino movies. It’s the only entry in the Tarantino canon that the former video store clerk didn’t direct – ignoring Oliver Stone’s butchering of his screenplay for Natural Born Killers a year later. Yet it is for this very reason it has also arguably aged the best (racial slurs and on-set violence aside).

Watched today, True Romance is a super-kinetic joyride, its whack-a-mole energy partly attributable to Tarantino’s script – there really is a surprise on every page – but also to Scott’s full-throttle direction. Just as significantly, the tics that would become problematic as Tarantino’s career progressed are barely present. The soundtrack isn’t intrusive in the manner of Reservoir Dogs or Pulp Fiction (the tinkling love theme, “You’re So Cool”, by Hans Zimmer, is a homage to Carl Orff’s “Gassenhauer”, as featured in Terrence Malick’s Badlands).

And, though it may seem a strange point to make about a film culminating in a three-way shoot out over a suitcase full of cocaine, the performances are more restrained than in Tarantino’s usual work .

Take the aforementioned Sicilian sequence in which Walken’s menacing consigliere verbally jousts with Hopper’s ex-cop. Knowing death is imminent, Hopper jokingly insults his interrogator’s Sicilian heritage by explaining how hundreds of years ago invading Moors changed the genetic makeup of the island’s population (yes, it really is that racist). What’s telling is that, even as they walk between comedy and high-tension, neither of the stars goes “full Tarantino”. The exchange works in part because it stops shy of over the top – it’s what keeps it from being mere prat-falling.

Contrast this with Walken’s next appearance in a Tarantino movie, as the ridiculous US Army Captain who appears in flashback to Bruce Willis’s boxer in Pulp Fiction. It’s just the wrong side of ridiculous and lacks the coiled tension of his face-off with Hopper.

As the title proclaims, True Romance is a tale of star-crossed lovers – Slater’s geeky comic store employee, Clarence Worley, and Arquette’s Alabama Whitman, a call girl hired for Clarence as a birthday gift. Their love blossoms. So to win Alabama’s freedom, Clarence confronts her pimp – Oldman’s dreadlocked Drexl Spivey. Sparks fly, along with bullets. With Drexl dead, Clarence flees, accidentally taking with him a suitcase full of cocaine that will serve as the movie’s MacGuffin. Somewhere along the way he and Alabama tie the knot.

Soon, he and Alabama depart Detroit for Los Angeles where, trying to offload the drugs, they tangle with cops, criminals and, worst of all, Hollywood producers.

The origins of the film go back to Tarantino’s days as a movie rental clerk at Video Archives on Manhattan Beach in Los Angeles (the comic store where Clarence works is regarded as a stand-in for Tarantino’s former place of employment). Sometime around 1988 colleague and occasional collaborator Roger Avary presented him with a 500-page script for a project titled The Open Road, with which he was struggling.

“It was an early screenplay of mine about the odd couple relationship between an uptight businessman and an out-of-control hitch-hiker who travel into a hellish Midwestern town together,” Avary would remember.

“Quentin… asks me if he can finish it. A year later it doesn’t resemble my original story in the slightest – he has, in fact, transformed it into something much more brilliant that will eventually become the bits and pieces that make up the foundations of True Romance, Natural Born Killers, and Pulp Fiction.”

The script gathered dust for several years. Then, in 1991, Tarantino blagged his way onto the set of Tony Scott’s The Last Boy Scout, where a friend worked as an assistant. Off the back of 1986’s Top Gun, Scott was regarded as one of Hollywood’s supreme hacks – a marshaller of flashy, soulless distractions. But Tarantino adored the panache of Scott’s directing and felt a kinship with the Englishman, in many ways another outsider in Tinseltown. So when the opportunity presented itself, he cornered Scott and pitched Reservoir Dogs and True Romance.

Intrigued and perhaps mindful of his own struggles in Hollywood (he’d been fired and rehired on three separate occasions on Top Gun), Scott agreed to cast his eye over the screenplays. “He gave me two scripts: True Romance, which was his first script, and Reservoir Dogs,” recalled Scott. ”I’m a terrible reader, but I read them both on a flight to Europe. By the time I landed, I wanted to make both of them into movies. When I told Quentin, he said, ‘You can only do one.’”

Tarantino was paid $50,000 for True Romance, which he used to fund Reservoir Dogs. That break-out movie was released the year before his collaboration with Scott and caused an instant sensation. The one-time video clerk and struggling actor was the toast of the industry and suddenly half the leading men in Hollywood wanted to be in True Romance.

Top Gun’s Val Kilmer lobbied Scott for the Tarantino surrogate role of Clarence. Scott went with Slater on the strength of his mercurial turn in misanthropic comedy Heathers. When they initially clashed over Clarence’s personality, Scott told the actor to watch Taxi Driver. He wanted some of Robert De Niro’s righteously crazy Travis Bickle in the character.

Kilmer would instead play the Elvis-like ”mentor” figure who appears as an apparition to Clarence in several sequences. Brad Pitt, for his part, got hold of the script and asked to play the perpetually stoned housemate, Floyd (Scott agreed, allowing Pitt to improvise most of his dialogue).

Even the usually fastidious Oldman was easily won over. He had lunch with Scott at the Four Seasons in LA, at which the director revealed that the plot of the movie was far too complicated to explain but that he wanted Oldman to play a white man who thinks he’s Rastafarian. Oldman said yes on the spot; such was his enthusiasm, he invited his 70-year-old mother to the set to watch his climactic death scene.

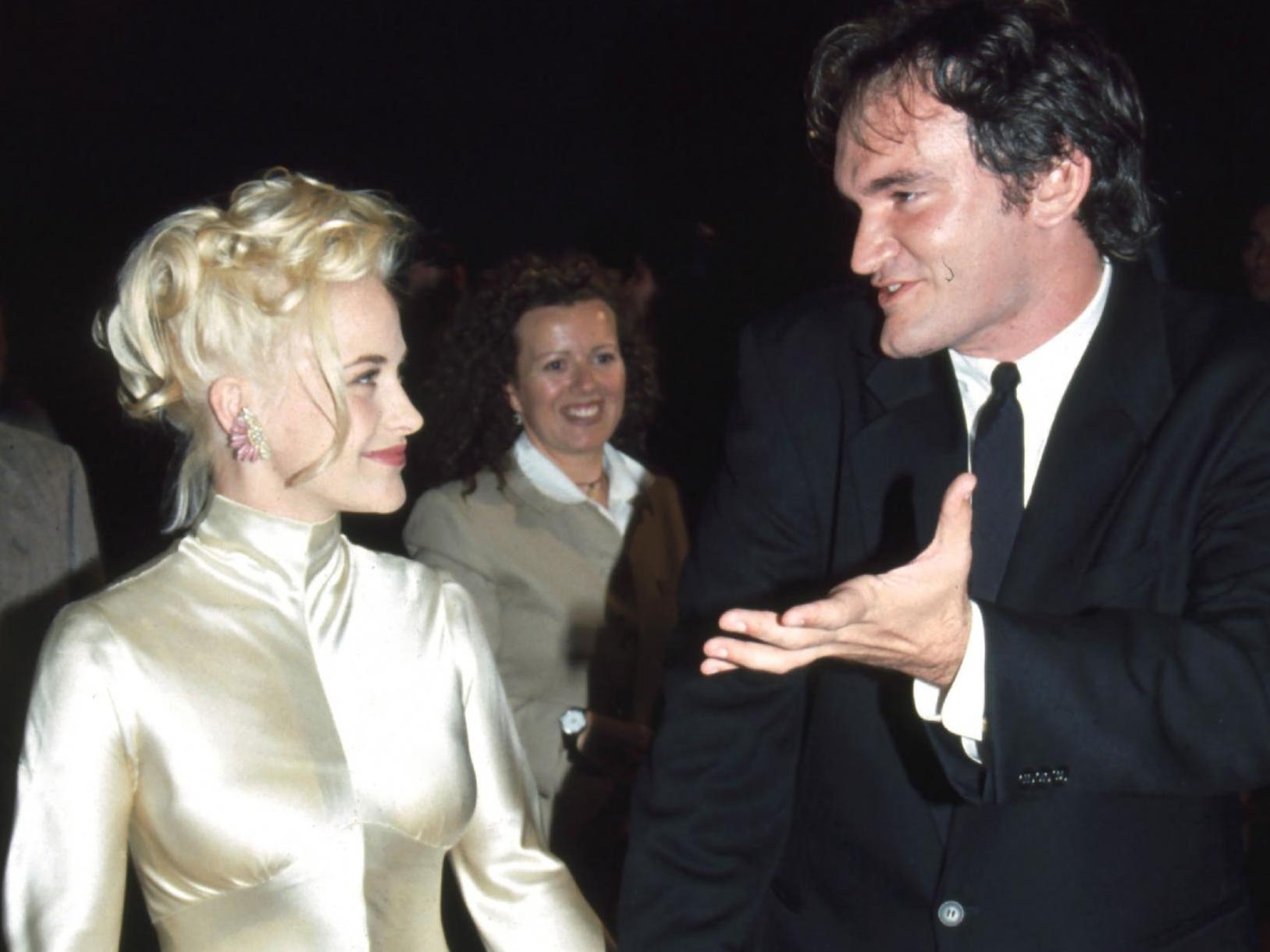

The casting of Alabama, however, was more problematic. The character had to be several things at once: a little ditzy, but with an air of melancholic wisdom and capable of holding her own in the scene in which she is beaten to a pulp by Gandolfini’s gangster, Virgil. Scott wanted Drew Barrymore, with whom he was reportedly obsessed. But she had already committed to another film.

Enter Arquette, best known at that point for being chased by Freddy Krueger in A Nightmare on Elm Street 3: Dream Warriors. Any doubts Scott had about her evaporated when he saw the effect she had on Slater, who was visibly besotted. The leads would become romantically involved; their chemistry gives their onscreen relationship a palpable fizzle. “It was love at first sight,” Slater recalled. “But working with Patricia was tricky, because I was in a relationship. We both made attempts to be professional, but at that age it was difficult.”

Arquette, it’s worth noting, was one of the few cast members not bowled over by Tarantino’s script. She was perhaps a little ahead of her time in blanching at all the racial slurs.

“My agent told me about this script for a Tony Scott movie,” she would tell Maxim magazine. “There was a lot I liked about it, but I didn’t like when Alabama was sort of racist. By now we’ve all gotten used to Quentin’s tone, but at the time I was somewhat shocked by it. I was asking myself, ‘What is this? Whoa!’ I don’t know if the line about being turned off by Persians was in the script [in the early diner scene Alabama lists “Persians” as a turn-off]. Actually, every time we shot that scene, I would say a different ethnic group – I wanted to be equally offensive to all people.”

True Romance occasionally tips into magic realism, with Clarence receiving visitations from Kilmer as a figure who can only be interpreted as ghost of Elvis – and who convinces him to risk everything for Alabama. Is Elvis real or a figment of Clarence’s potentially unhinged mind? Both Scott and Tarantino have said it’s up to the viewer to decide.

Tarantino’s original True Romance script serves as a trial run for Pulp Fiction. As with the later movie, his version of the story jumps all over the place, so that it’s not initially clear how Clarence and Alabama crossed paths or why they’re fleeing Detroit.

Tarantino starts with Clarence in a seedy bar, where he is feeding an unimpressed women his best chat up lines concerning his love for Elvis. Then, after the credits, we bounce forward to the on-the-run Clarence and Alabama fetching up at Clarence’s father (Hopper), with a suitcase full of cocaine. Only later, in flashback, do we learn how they met and of Clarence’s fight with Drexl.

Scott attempted to work with this experimental framework before throwing in the towel and opting for a straightforward chronological approach (he retains the original opening of Clarence in the bar). “From what I’ve heard, he tried my structure but went nuts with it – went far beyond what I did,” said Tarantino. “So apparently there’s this really metaphysical avant-garde cut of True Romance floating around out there somewhere.”

The director also changed the original ending in which Clarence dies in the cocaine shoot-out. Instead, the character comes back to life and he and Alabama live happy ever after in Mexico (Arquette’s real son plays their child). Tarantino initially objected – but upon watching the final movie agreed that Clarence surviving was more consistent with the tone of Scott’s film.

One aspect of True Romance generally unremarked upon is the fact that Shakespeare’s “something is rotten in the state of Denmark” line is referenced twice.

“You know I knew something must be rotten in Denmark,” sighs Clarence, when Alabama reveals she is a prostitute. Later, detective Nicky Dimes ( the late Chris Penn) tells his chief “We knew something was rotten in Denmark,” after discovering a packet of Clarence and Alabama’s purloined cocaine in the possession of actor Elliot Blitzer (Bronson Pinchot), their go-between in the impending deal to sell on the drugs.

That Tarantino was explicitly referencing Hamlet was hypothesised the year after True Romance’s release, in a Los Angeles Times essay by poet and jazz critic Stanley Crouch. He described the film as “an ingenious variation of Hamlet”, with “Denmark” representing America’s criminal underbelly, “the dope world of casual sadism and murder”.

Quite what the plot of True Romance has in common with that of Hamlet is not immediately apparent – beyond the fact both feature out-of-control characters in a heightened reality and a visiting ghost (the King instead of “King Hamlet”). Perhaps Tarantino intended it as an early version of the magic suitcase from Pulp Fiction – a mystery never meant to be solved.

Before his tragic death, Scott was regarded as the hack yin to brother Ridley’s visionary yang. Yet True Romance pleads the opposite case, arguing that he is a master of style, pushing mainstream cinema to its aesthetic limits. The violence, in particular, has a hyper-real, comic book quality. Far from lessening the impact, this makes the bruises and bullet wounds seem even bloodier.

Without question, Tarantino’s jacked-up Bonnie and Clyde-like script – a tribute to Malick’s lovers-on-the-lam classic Badlands – makes True Romance the film it is. But it is equally indisputable that Scott’s mastery of action and his blistering fast-cuts are the source of the movie’s jittery energy, its crazy-eyed rush.

There is, moreover, a case that it is this aspect of True Romance that has aged the best and that it’s the Tarantino-isms – the “n” word, the casual sadism – that feel like flotsam from less enlightened times.

“One of the things that’s actually been kind of gratifying about reading all of this internet stuff, where everyone’s talking about their favourite Tony Scott movie, is people were not saying that in 1990,” Tarantino would mark after Scott’s passing. “People used to say ‘Oh, he’s a commercial hack. His stuff is bullshit.’ And I loved his shit. I thought it was fantastic.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks