The Independent's journalism is supported by our readers. When you purchase through links on our site, we may earn commission.

I was with Oasis from the start – they’re a band that wouldn’t exist in 2025

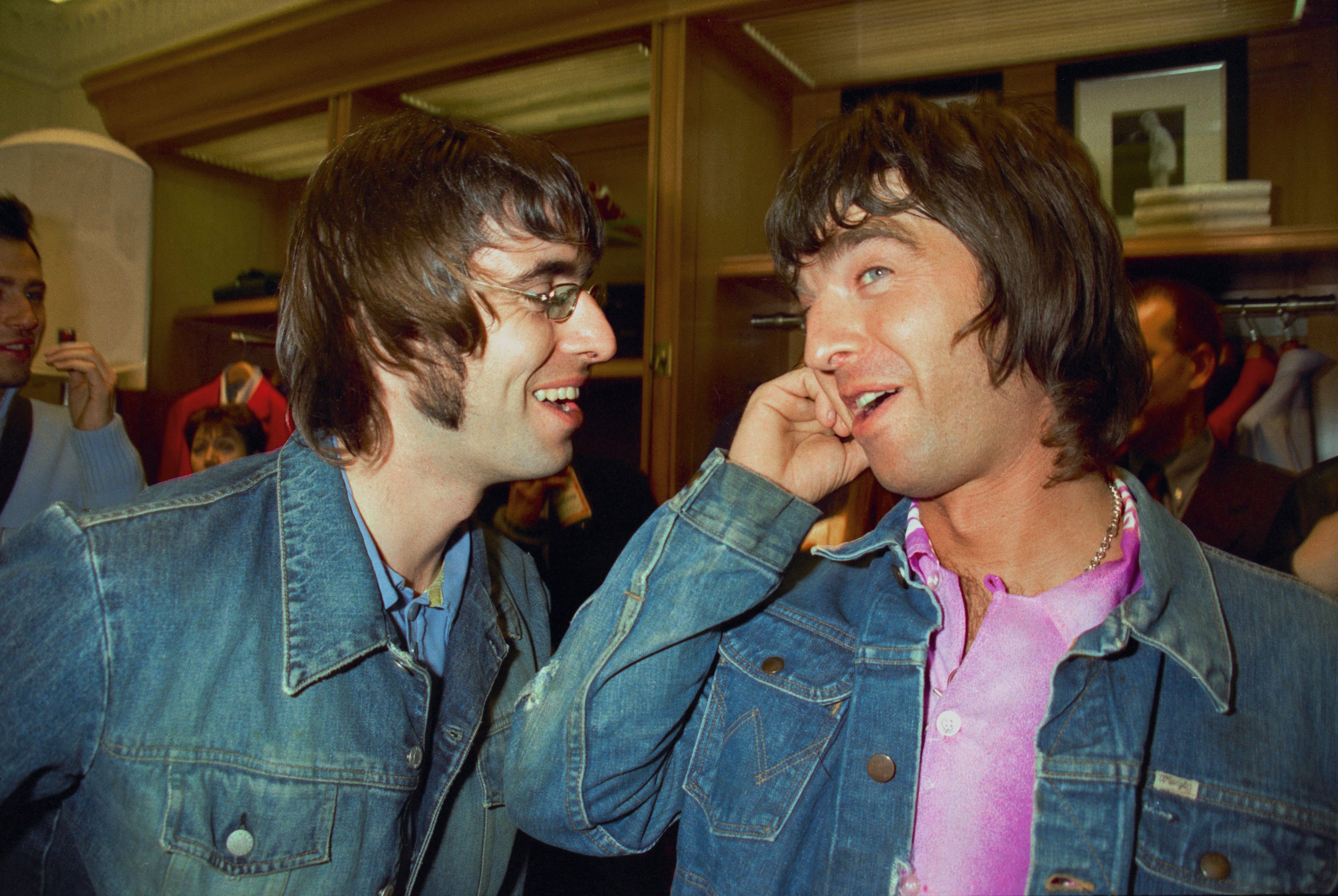

James Brown was there when the Oasis story started and saw the Gallagher brothers grow from lads to dads who could still cause chaos in the Groucho Club before school pickup time. He reflects on the band who are now connecting with a new generation – and for good reason too

In the spring of 1994, I was working late putting Gary Oldman, Leslie Nielsen and Elle Macpherson on the covers of the first issues of what would quickly become the magazine of the decade, loaded. We were launching a funny magazine that crossed music, football, clubbing and drinking. The next morning five of the staff poured into the office excitedly yelling about a new band they’d seen the night before at the 100 Club in Oxford Street.

“You’ve got to come and see this band, they’re brilliant, they look like football fans playing Sex Pistols songs. The publicist let us all in through the fire doors at the back.”

A few weeks later they went to see them again at The Astoria, a huge theatre in Tottenham Court Road, that's how fast they were growing. “Honestly you will love this band,” continued the young staff writer. “They played a 10-minute version of ‘I Am The Walrus’.”

At the time, no one else would have the audacity to attempt to improve on a Beatles classic, but it was typical of the front of Noel and Liam Gallagher, which was as loud as their songs. The band were called Oasis, which, in 1994, was a popular name for hairdresser salons, but quickly became synonymous with the sounds and antics of The Gallagher brothers, Bonehead, Guigsy and co.

These were the boys from the back of the class, their names sounded like they should be in The Bash Street Kids. Just as The 2 Tone bands like The Specials, The Beat and Madness had done, Oasis had a natural tough playground appeal which, once they’d broken onto Radio One, The Word and Top of the Pops, helped speed up their rising popularity.

We immediately sent a journalist and photographer to Manchester to shoot them in their casual attire outside Man City’s Maine Road. The lead singer Liam looked like he was about to kick the photographer’s head in.

They were terrace boys who wore their musical influences all over their sleeves and didn’t attempt to disguise who their heroes were. They were a cross of The Beatles, Pistols, Happy Mondays, T-Rex and Jesus and Mary Chain. All swagger and feedback and big booming bass, drums and lead guitars. They were fantastic. A breath of fresh air.

Their music was immediate, loud, fast blitzkrieg pop, but the speed of their success was the most astonishing thing about them. They seemed unstoppable, on the rampage. And like the magazine, they’d captured something of the time and just continued to grow and grow, breaking sales records, scooping up awards. And annoying people who’d lost or maybe never had any sense of fun.

I first met them in September, a few weeks after the release of their now iconic album Definitely, Maybe when they arrived unannounced with an ex-NME colleague of mine at my 29th birthday party. They said they loved the mag and Noel offered to write a theme tune if we ever wanted to make a TV show.

By the time two hours of free booze had been drunk, a girl came up to me, pointed at Oasis and said: “Those lads have nicked my handbag.” I explained they’d just had their first number one album and they were probably past the handbag nicking stage. Sure enough, it appeared soon after underneath the seat she’d left it on.

The mid-Nineties genuinely was such a different time, the pre-social media age, people who looked like handbag thieves were fast becoming modern icons and heroes. The films (Trainspotting, Pulp Fiction, Twin Town) and the books (The Beach, Are You Experienced, Trainspotting again) combined a sense of recklessness with big beaming spotlights of hope.

Within a few years of loaded and Oasis launching, the Tories had been seen off and the prime minister-to-be was playing head tennis with Newcastle United manager and former England star Kevin Keegan.

There was a looseness and unpredictability to our lives and the nights out we had then. If a mate didn’t arrive at a pub at an agreed time there was no instant messaging, you had to just wait and see if they showed up, or make new friends.

You actually talked to each other to find out who you were drinking with or snogging; you couldn’t run an instant forensic analysis of people via Instagram and TikTok. How we got on in our careers was different too.

The hardship of the Eighties, when the miner’s strike and mass unemployment had divided the country, sharpened the ambitions of many of us leaving school and refusing to accept the limitation of the dole life the Thatcher government was offering us.

A decade on, after we started our own black market cottage businesses, there were working-class people in their mid-twenties running massively popular clubs, record labels, bands, magazines and fashion companies.

We’d succeeded despite the Tory years of government; we’d revolted against them rather than been inspired or helped by them. Noel Gallagher and his Creation Records label boss Alan McGee were typical of the generation who’d learnt more from politicised bands like The Jam and The Clash than our teachers and career officers.

We had Noel on our loaded cover twice, he was so recognisable that one Christmas in conversation with Irvine Welsh, we simply put a cropped shot of his famous eyebrows and haircut on the front of the magazine. A far cry from the permanent array of semi-naked women the mags that followed us would serve on their covers.

When I later put Liam and Noel on the cover of GQ the interview took place on the same day they’d drunkenly challenged the Rolling Stones and Beatles to a fight on Primrose Hill on Radio One. Some of their anecdotes in the article were so wild they ended up costing Conde Nast £25,000 in libel fees to George Harrison’s son, Dhani.

This kind of chaos married with the aggression, the humour, the fraternal infighting, mixed with their defining anthems, not only made them the band of the decade but preserved a sort of authenticity that made them attractive to subsequent generations.

They predate the x-factorisation and pop idolisation of music. They sang themselves famous in dark clubs not on brightly lit predestined talent shows. There remains a rawness to their original work that our children love.

When he was about seven, my eldest son, who’s now 23, came home from primary school and asked “Dad, are you Oasis or Blur?” Like at my late-Seventies secondary school in Leeds, where we’d been mods, punks, teds or rude boys, the Britpop rivalry was one of the last great youth cult opportunities for kids to attach themselves to a tribe.

His next question was: “Did you ever meet Oasis?” A year later I introduced him to them in their dressing room at the FIB Benicassim Festival in Spain. It’s now my son’s generation as well as those hankering for their own youth that are looking to snap up the tickets to the band’s 2025 reunion.

I think it’s because Oasis was born in an era that wasn’t washed clean and controlled by the digitalisation of communication and self-representation. By the political polishing of what’s accepted in polite society. It’s hard to imagine a band as caustic and unsophisticated would be welcomed today. It’s Liam’s more laidback older self that’s made him such a star of X/Twitter; the younger him would have been cancelled years ago.

The most rock ’n’ roll time I had with them was interviewing Liam in 2005 when our lives had moved on a bit and the wild men of rock ’n’ roll and men’s mags had both become dads. He was most excited to hear about me taking my son to Diggerland, a theme park in Rochester Kent, which was a muddy field full of yellow JCBs loved by the Bob the Builder generation.

After our interview, I took him over to the Groucho Club to meet Gazza. When an incredibly inebriated Gazza pleaded with Liam to sing for him and Liam refused things started to get slightly tense until I started the opening line of the theme to SpongeBob SquarePants, which I knew Liam watched.

He immediately joined in and Gazza was delighted, but Liam had the last laugh when he let loose with a fire extinguisher and pelted out of the club as we both set off to pick our kids up from school. It was hard to encounter the Gallaghers and not come away with something worth retelling.

And now they’re back in the month when the leading pop culture media podcast, The Rest Is Entertainment, just asked “Where have all the bands gone from the charts?” If they record, as well as play live, this could change.

Double divorces for the brothers might have made the reunion seem more attractive now but culturally, a new generation is yearning to see them. What goes around comes around. Like the late Nineties, Labour are in power, a credible version of the Sex Pistols are playing live and England’s football team have nearly won a tournament.

They’ve got a year to manage their traditionally volatile relationship before they play live together again. Here’s hoping they will make it because it will definitely be worth it.

James Brown’s memoir of life in the Nineties ‘Animal House’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks