Keep rollin’ rollin’: Are Limp Bizkit still the ultimate cultural punchline?

The nu-metallers became the scapegoats for Y2K frat-boy nastiness but, 20 years since their last giant album, Adam White asks whether it’s possible to view their significance in musical history any differently…

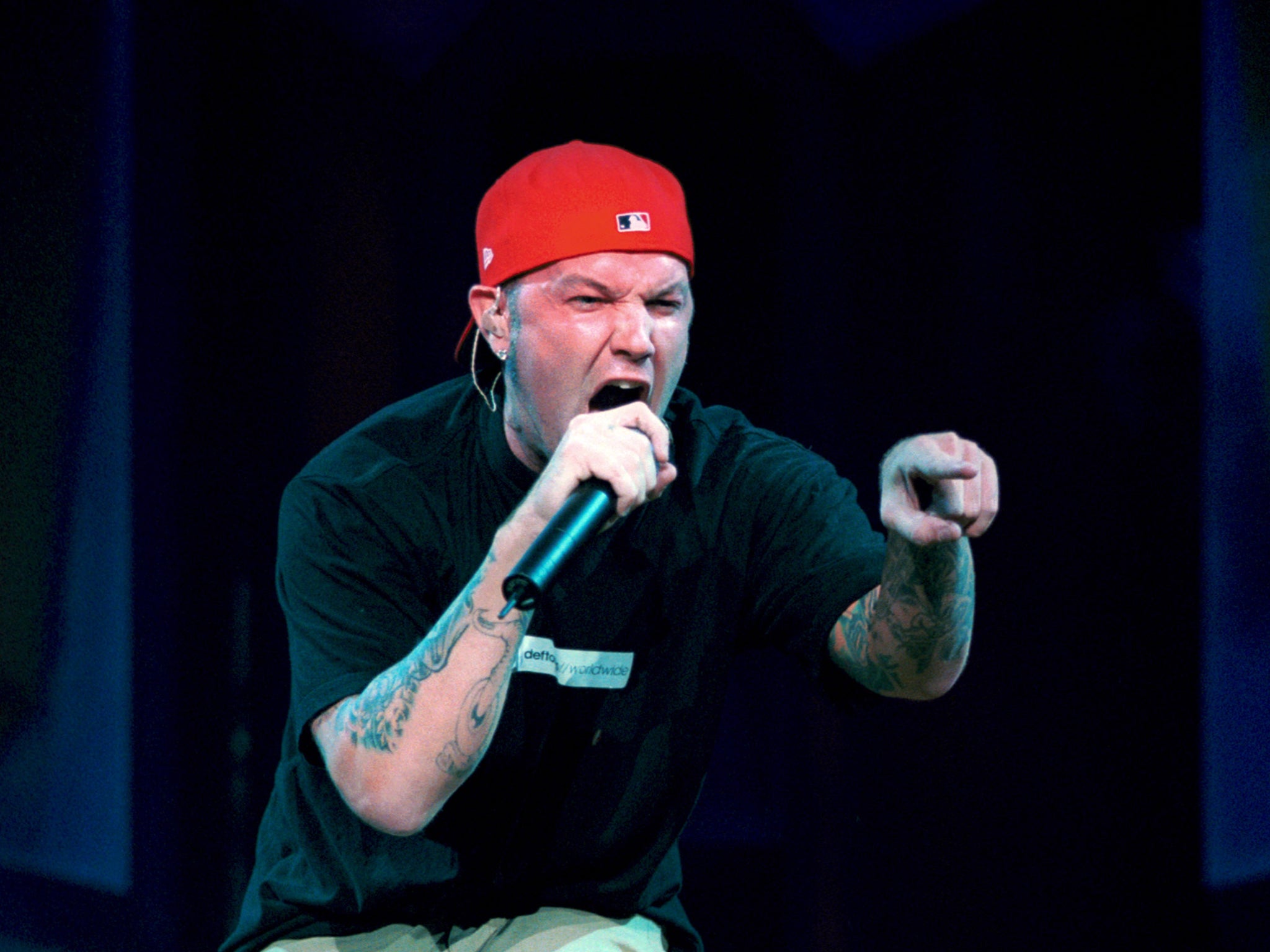

In a nondescript building in Austin, Texas, all of the city’s waste, rubbish and animal remains pass through an enormous recycling operation, turning trash into something useful. But when the city asked its citizens to help rename their waste services, back in 2011, an unavoidable number of people polled that they wanted to call it the Fred Durst Society of the Humanities and Arts. It was a withering gesture to the Limp Bizkit frontman, famous for his chinstrap beard, backwards cap and for being the absolute worst. And it was a sign that, even a decade after their sweary peak, they were still very much a cultural punchline.

The Boaty McBoatface-style hijack spoke to the group’s long legacy of dismissive mockery. Responsible for hits like “Nookie”, “Rollin’” and “Break Stuff”, the Bizkits were Britney-bothering frat bros powered by Lynx body spray, cherry lubricant and white male hubris; the unrepentantly juvenile face of the nu-metal genre that fused hip-hop and rock with the lousier leftovers of grunge. Spearheaded by Korn, and subsequently dominated by the likes of System of a Down, Papa Roach and Staind, nu-metal came to monopolise late Nineties rock, sparking moral outrage and a significant backlash. Limp Bizkit was often regarded as the flashy runt of the litter, with today only Nickelback inspiring as much collective wrath, used as a similar shorthand for the misery bad rock music has apparently wrought upon the world. In Limp Bizkit’s case, their treatment was both entirely correct and incredibly hyperbolic.

Twenty years ago this week, Limp Bizkit hit a commercial peak they would never again revisit. Chocolate Starfish and the Hot Dog Flavoured Water, their horrifically titled third album, was their magnum opus – a shambolic and petulant if weirdly pleasurable racket built on themes of romantic resentment, gold-chain arrogance and teenage angst. That Durst was pushing 30 at the time of recording was a mere technicality. The album is as miserable and bitter as a 14-year-old’s tantrum, set aflame by thrashing guitars, squelchy bass and turntable scratches courtesy of DJ Lethal and guitarist and songwriter Wes Borland, always the group’s secret weapon.

Lyrically, it’s an attack album. Durst rants about his ex, the vultures riding his coattails, “haters”, and society at large. “Life’s just a little f****d up,” he raps on “My Generation”. “Generation X, generation strange / Sun don’t even shine through our window pane.” He also raps horribly, his rhymes banal, his delivery a persistent, snarky, high-pitched croak. He has undeniable magnetism, though, a frontman as noxious as he is funny. There was always a deliberate Farrelly Brothers-style comedy to Limp Bizkit after all, their name conjuring images of masturbatory gross-out, the “Chocolate Starfish” of their third album title equally crude. At Ozzfest 1998, they emerged on stage through a giant toilet bowl. “We’re definitely a dumb rock band,” Borland told Rolling Stone ahead of the album’s release, in an acknowledgement that Limp Bizkit had its tongue firmly implanted in its cheek.

Savvy networking and deliberate provocation made the band’s name pre-Chocolate Starfish. Invited to tour with Korn after impressing that group’s frontman, Jonathan Davis, Limp Bizkit became rapidly notorious for their anarchic swagger, gleeful antagonism towards the press and how easily they seemed to glide into heavy rotation on MTV. If their debut album, 1997’s Three Dollar Bill, Y’all, seemed comprised of nothing but Korn knock-offs, “Nookie”, the lead single from their 1998 follow-up Significant Other, set the template for much of their future material – these were scorned boys partying through the pain and unexpectedly capturing the cultural mood. Durst, nothing if not a slick careerist, was even declared senior vice president of the group’s record label within months of “Nookie” flying up the charts. At the same time, battle lines were being drawn between the band’s hardcore fans and those looking on in horror.

“There was a fairly universal lack of enthusiasm from the staff at NME to cover any of those bands and Limp Bizkit certainly foremost amongst them,” remembers NME editor at the time Ben Knowles. “It was just so dumb and crude and offensive and sexist. It was almost like one of those post-American Pie films come to life in musical form.” Readers regularly sent letters complaining about the magazine granting them any acknowledgement, “even through the caveat that we’d only feature them to challenge them”, he adds. “This was just a waste of good trees in their eyes.”

Lifting from the angry-boy energy of its preceding albums, Chocolate Starfish is a great mood swing record: it’s about needing to wreck and destroy to feel something, with hazy mid-tempos about secret desires and maudlin feelings breaking up the vitriol. Considering it flows so haphazardly, emotions all frayed and heightened, it’s not surprising that teenagers flocked to it.

“Limp Bizkit came around at the right time for me,” says one-time superfan Kris, who was in his teens when “Rollin’” hit number one on the UK singles chart. “They were pissed off at the world and hated everything, and I felt the same way. Looking back, it wasn’t always obvious what they were angry about, but that doesn’t matter when you’re 17. It’s easy to identify with someone who is expressing something you also feel deep down inside, even if you can’t articulate what that thing is.”

It’s that lack of eloquence that made Limp Bizkit oddly powerful. Durst and his band weren’t poets or miniature Kurt Cobains sinking into artful woe but brawny meat-heads acting on impulse and finding freedom in wanton destruction.

“He was really one of nu-metal’s few big, outspoken faces,” says Jason Arnopp, author of Ghoster and, at the time, the deputy editor of Kerrang! – sales of which skyrocketed when it became a major advocate for the nu-metal scene. “Korn and Slipknot were incredible bands, but Jonathan Davis was a sensitive introvert and Slipknot initially felt like a faceless collective. Lyrically and sonically, Limp Bizkit fitted nu-metal’s cauldron of styles, but they had their own sound. If there was one element that spoke loudly to teens back then, it was this kind of incoherent rage. They helped listeners purge their frustrations.”

Durst was a bullied and disaffected white boy from Jacksonville, Florida, a self-described “f***ing loser” who joined the navy in lieu of any other options and also to impress his cop father. It apparently didn’t work, and he was discharged after 18 “soul-crushing” months, he told Rolling Stone in 2000. Durst’s story was a familiar one, particularly for young, blue-collar American males, his overgrown juvenilia, testosterone-driven insecurity and lazy arrogance as a rock star subsequently inevitable. That he became a hero to kids just like him even more so.

Durst was Limp Bizkit’s achilles heel as much as he was their star. Early into their fame, a narrative had emerged determining that Limp Bizkit were bad men making bad music and birthing a generation of proto-incels in the process. Their concerts were “orgies of lewdness tinged with hate,” wrote revered music critic Ann Powers in The New York Times, promoting the idea of women as sexual objects worthy of ritualistic disrespect or worse if they cheat or romantically reject the men lusting after them. “Boneheaded sexism is on the rise throughout the rock scene,” Powers added. One NME cover featured a picture of Durst alongside the headline: “Is this the most hated man in rock?”

“I met him several times, and always liked him,” Arnopp recalls. “He was a pretty serious, ambitious, driven character who claimed that obsessive compulsive disorder gave him a meticulous attention to detail, but also tormented him. He became disgruntled with the press, and he would rant about ‘haters’ a lot, but I came to wonder if he rather saw the benefits of remaining the underdog in some way. Proving everybody wrong certainly served to motivate him.”

The treatment Durst received from the press seemed to stem from his behaviour outside the studio, or on tracks that even the band themselves would come to regret. He was gleefully driven by money and celebrity, indifferent to the time the band’s label paid a radio station $5,000 to play their music, and boasting of his friendships with everyone from Ben Stiller to Kate Hudson to George Lucas. His ludicrous misogyny, notably a rage fit on the 1998 track “Don’t Go Off Wandering” over a woman who “mentally molested” him but withheld sex, should have made the group’s second album Significant Other unlistenable in 1998, let alone 2020. And his feuds were regularly embarrassing – he wasn’t Courtney Love deliciously dismissing her lessers, but your paunchy third cousin whining about similar unfortunates.

For the band as a whole, there was also their personal Altamont. Limp Bizkit often left cosmetic destruction in their wake, encouraging audiences to smash up venues and bash into one another in mosh pits, but they were also associated, if tangentially, with real tragedy. Woodstock ’99 was a disastrous revival of the legendary hippie festival that was live-streamed by MTV, with Limp Bizkit on the bill along with Red Hot Chili Peppers, Metallica, Alanis Morissette and a host of other rock acts. The weekend was blighted by horror – a woman was reportedly raped in the audience during Limp Bizkit’s set, one of a horrifying number of sexual assaults that allegedly occurred across the three-day event, while the band was blamed for inciting the riots and looting that occurred in the wake of their performance.

In 2019, The Ringer re-examined the tragedies of the festival and determined that Limp Bizkit weren’t the root cause for its failings as much as the media at the time seemed to suggest. Oppressive heat, overcrowding and poor facilities created a tinderbox, with many acts who played the festival suggesting Limp Bizkit were used as “scapegoats” by the media. “I don’t think that the riots shoulda happened, period,” Korn’s Jonathan Davis told the site. “That was some bulls***. But I think Bizkit being blamed for it is because they were the heavy band. We were the outlaws at that time. I don’t think it was their f*****g fault.”

But the narrative that emerged, of Durst recklessly driving volatility in the crowd, wasn’t exactly quelled by the group’s reaction to it. In their subsequent music video for single “Re-Examined”, they are put on trial for the events of Woodstock ‘99 and executed via drowning. It was a misjudged decision to put two fingers up to criticism, rather than acknowledging that they could have done better. Their reputation in the music press, already dismissive, only darkened.

“Limp Bizkit’s songs revert to an almost pre-sentient, inchoate rage, the same selfish, knucklehead reaction that fuels gun-toting high-school killers,” wrote The Independent’s review of Chocolate Starfish, contrasting teen-driven metal with the Columbine Massacre just as flippantly as those who blamed the tragedy on Marilyn Manson.

Pre-social media, Woodstock ’99 didn’t have an immediate effect on Limp Bizkit’s popularity outside of critic circles. Chocolate Starfish was their biggest album to date, breaking the record for highest first-week sales for a rock band.

“There was a degree of snobbery and disdain to the criticism aimed at them, which people who liked them just didn’t have,” says Knowles. “If you were going to the Reading Festival in August of 2000, if it was like ‘Limp Bizkit world’. That generation of 16 to 22 year olds, they were 100 per cent sold. They had the T-shirts, everybody was wearing backwards red baseball caps, and there was no sort of irony in it. You then realised that NME keeping that slightly arch tone meant that we were always going to fail to engage with these artists. I think it was about six months later that Kerrang!’s sales overtook NME’s for the first time ever.”

Limp Bizkit, for a few years, dominated the industry, before crashing spectacularly. A year after the release of Chocolate Starfish, a fan was crushed to death in the moshpit during the band’s set at an Australian music festival, and Borland would depart the group soon after. Durst, forever trailed by bad press, seemed to spiral, storming off stage while the band toured with Metallica – “F**k Fred Durst” had been chanted by the crowd. The group’s fourth album, Results May Vary, traded rock-rap for gloomier emoting, draining the band of their exhilarating wrongheadedness. They would disband soon after, reuniting in 2009 for world tours and occasional recording.

Nu-metal itself would seem to crumble alongside them. It proved a commercial flash in the pan, with history determining Limp Bizkit their most graceless alumni. It is true that they embodied the feather-light pop end of the genre, with none of the surprising depth of Korn, nor the elegant inventiveness of Linkin Park. They were, however, an imperfect vessel for adolescent chaos in all its colours.

“Whether we like to admit it or not, young people sometimes want to break stuff and be dumb and stupid, and Limp Bizkit gave a voice to that,” Kris adds. “I’m older now, I like to think that I’ve matured, but there’s still a part of me that loves that sound, the crashing and the f***ing about. It’s me when I was 16/17, and whether or not it’s considered stupid or embarrassing or people say that they were, you know, a stain on rock or whatever, they meant a lot to me and spoke to me. I’ll always be grateful for that.”

“That angry, rap/rock crossover music spoke in a direct and emotional way to the frustrations of teenagers, and it certainly has echoes through the music you see today,” Knowles says, naming Billie Eilish as one example of a slight, potentially unintentional, scion of Durst. “That sort of music is only going to continue to speak to teenagers, but in a way where they get it and journalists in their twenties will continue to slightly sneer at it.”

Limp Bizkit were obnoxious and destructive because America is obnoxious and destructive; they were a group that embraced ignorance and thoughtlessness because that’s what reckless young men tend to do. In truth, their reputation always felt appropriate. No one likes teenage boys, with their bad facial hair and boorish lens on the world, even less so grown men acting much the same, but it’s also important to acknowledge them, and ensure that they’re seen and heard and don’t fall through the cracks. And through the journey of Durst, now a filmmaker and impressively quiet relic of 2000s pop culture, impart the message that you can be ridiculous, asinine and crude as a young man in the world, but then grow the hell up.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks