Metallica: ‘Everyone is so tightly wound, like they’re gunning for a fight’

If anyone knows about survival, it’s the heavy metal band who’ve lasted four decades. As they release a recording of their live orchestra performance, the thrash legends tell Roisin O'Connor how they’ve been waiting out the pandemic and why we need to move forwards

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Lars Ulrich has been having two recurring dreams. In one, the Metallica co-founder is trying to reach his drum kit, but the stool is too far away and his sticks are made of rubber. In the other, he’s at the top of a skyscraper that sways, cartoon-style, back and forth, and holding on for dear life. “Maybe a few hours with a psychiatrist could explain it,” he laughs down the phone from his home in San Francisco.

Instead, Ulrich has been discussing these dreams with his bandmates. They’ve been holding weekly Zoom chats throughout lockdown, in which they talk about new projects, including the just-released S&M2 – a live recording of Metallica’s performances last year with the San Francisco symphony orchestra. It’s the latest offering from a band who swatted away their competition upon arrival with massive, chugging riffs, subtly layered production and dynamic arrangements. They’re renowned for their willingness to push themselves beyond the traditional expectations of a heavy metal band, hence the sitar sound on “Wherever I May Roam”, from their self-titled fifth album (1992), and the string section on “Nothing Else Matters”.

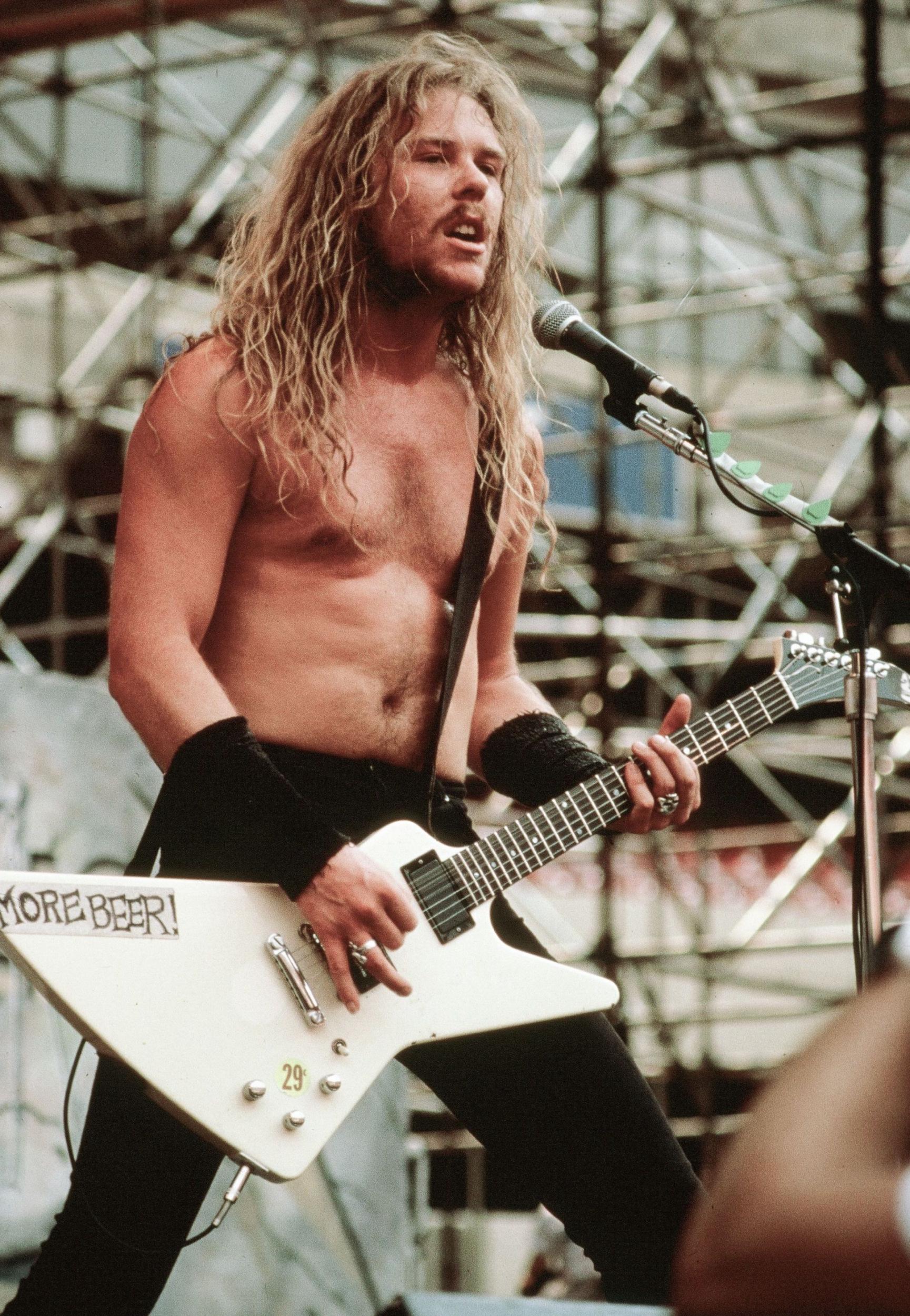

When Covid-19 put the music industry on pause, Metallica were already dealing with a different setback. In September last year, the band announced the postponement of their Australia and New Zealand tours in order for frontman James Hetfield to return to rehab for addiction treatment. Metallica’s publicist has requested that I don’t ask about the rehab itself, but Ulrich assures me that “everybody’s well... [each] dealing with their own version of this” – this being the pandemic – “just like everybody else all over the world”.

“There’s nothing to complain about,” he says of his personal experience of the here and now. “An unexpected treat in these dark times” was his two eldest children moving back in. “I get this euphoric feeling when they come home [from college],” he continues. “Then it’s like… s***. Am I older than I think I am?!” The family has had wonderful moments of sharing music and film. Yet he senses how difficult it is for the younger generation to see past the Covid-19 fog, to a future where live entertainment, employment and socialising are possible once more. “And these kids take quarantining very seriously.”

It’s touching to hear these heavy metal behemoths – tattooed (with the exception of Ulrich, who famously dislikes them), fit and muscular even in their mid-fifties – open up about the serenity of their home lives. In a separate call, bassist Robert Trujillo reveals he’s been learning to cook dinner for his family (spaghetti bolognese is his go-to) at home in southern California. He’s thinking about taking up cycling, too, inspired by his friend Mike Bordin, drummer for the rock band Faith No More. “Honestly, before this pandemic, I never would have said that,” he admits, laughing. “I don’t know, man. There’s a lot of room to grow. It’s a good time to figure out what you wanna do – you move forwards rather than back.”

Metallica are a band that have always looked to the future. Next year will mark 40 years since they formed in Los Angeles in 1981, an achievement few other bands, even heritage ones, can claim. They’ve survived loss – most notably the death of bassist Cliff Burton in 1986 – and several lineup changes. Their debut album, Kill ’Em All, redefined a genre and was described by critics as “the true birth of thrash”. And after 10 studio albums, world tours, an infamous legal battle with Napster, Grammy Awards (plus one notorious snub in favour of Jethro Tull in 1989), an induction into the Rock & Roll Hall of Fame, marriage, kids, divorce, marriage again… they’re still here, trying new things.

I wonder aloud to Ulrich whether the fact that he and Hetfield were experiencing similar life moments at the same time had any bearing on that oft-discussed longevity. A 1997 interview with The Independent detailed the band’s members going through pivotal changes: Hetfield’s wife, Francesca, was expecting their first child, while Ulrich was also settling into family life.

“When you’ve been in a band for 400 years like we have, you have lots of mile markers,” Ulrich says now. “And at around the same time, we all made this transition from rock and roll delinquents to more… family-orientated choices. That’s pretty significant for how the Metallica story has played out. It also probably played a significant part in the fact that you and I are talking right now.”

It’s taken a lot of work, he notes, and the band still have their ups and downs, many of which are addressed in the unflinching 2004 documentary Some Kind of Monster, in which the band were at one point so fractured that their management sent them to a “performance enhancement coach” to sort it out. “We’re very transparent in letting fans be a part of our journey,” says Ulrich, while Trujillo, who replaced bassist Jason Newsted after he resigned in 2003, points out that they’re “a team that experiments”, one made up of four incredibly forceful personalities. “As individuals, we’re so different, but we’re family,” he says. “And we always try to understand each other.” He recalls his own, intense induction into the band. There certainly wasn’t any handholding. “I was chasing the catalogue every fricking show, because I didn’t know what I was gonna play!” he recalls. “You can’t just be a good musician and join Metallica. Being able to have a relationship with different personalities is vital.”

This ability to communicate proved essential for the S&M2 concerts. For a band that thrives on an “anything could happen” attitude at their live shows, working with an orchestra was a daunting prospect. “We know each other well enough that when something derails we can make it work,” Ulrich says. “But when something derails with this many people, it can turn into a bit of a clusterf***.” That said, he adds, “As a band, we love being out of our comfort zones.”

The S&M2 album is an extraordinary accomplishment. Where many live albums can fall flat by removing the energy of the performance through over-production, S&M2 crackles and spits. There are mind-boggling solos from guitarist Kirk Hammett, and – in the video recording – beaming smiles from the orchestra as they accompany his finger-blistering shreds. Metallica’s music is often cinematic in its ambition and scope; for years, the band has walked onstage to Ennio Morricone’s “Ecstasy of Gold”. Now, they perform a rousing rendition of their own. Classical and metal might seem like an unusual pairing but this is not Metallica’s first rodeo. An arrangement by the late composer Michael Kamen, who first persuaded Metallica to do an orchestra performance for 1999’s S&M, adds some 007 drama to the already epic sweep of “The Call of Ktulu” (Kamen scored Licence to Kill).

Among the most poignant moments is a solo performance of Cliff Burton’s “Anesthesia (Pulling Teeth)” by SFS member Scott Pingel on the stand-up bass. Burton’s 94-year-old father, who died just a few months after the concerts took place, was moved to tears. Trujillo suggests that Burton’s passion for classical music – Bach in particular – “laid the groundwork” for Metallica’s foray into the genre.

Trujillo, who brought his flamenco influences to the band when he joined, also believes that each member is a product of their environment, which has helped to embolden Metallica’s sound with more varied musical styles than your average metal band. “When I hear riffs from James, I hear the groove of south-central LA but also the danger,” he says. “Kirk is from San Francisco, which was an R&B-driven neighbourhood. From the classical sound to being chased by gangbangers in LA… all of that finds its place in our music.”

Ulrich says that the band has never taken their success for granted, but it does allow them to continue operating “in our own little universe”. He’s noted many times before that he’s not one to dwell on the past, but he does acknowledge the ways Metallica have changed over the years. “We’re getting much better at setting boundaries for ourselves,” he says. “In the wake of our success, we have the freedom to roll along. We’re super lucky we don’t have to play by the rules.”

I hear Ulrich wince slightly when I broach a comment he made in a 2016 interview, that he’d move back to his native Denmark if Donald Trump won the US presidency. The election in November has thrown his comments into focus once more. But it transpires that Ulrich’s remark had more to do with him being drawn back to his roots: “I feel a deeper connection to where I came from as I get older,” he explains, “and I think in whatever time I have left, I’d like to spend more of my time there.” He loves the US, he clarifies. “You and I could spend hours talking about what I love about America as a place and as an ideal. So when I say I think about moving back to Denmark… that’s not a middle finger to America.”

Compared to so many other artists of late, Metallica tend not to wade into politics; their music speaks of unnamed authority figures that must be challenged, and they avoid calling out any explicit real-life characters. More than anything, their music provides an outlet for fans (and the band themselves) to channel all their rage, fear and uncertainty – but also their hope for the future.

“There are so many people choosing violence and division right now,” Trujillo says. “I feel everyone is so tightly wound, like they’re gunning for a fight. For me, it’s better to be careful than to pursue aggression.”

Ulrich shares a similar view, recalling the unity he sees during the band’s shows. “We played Abu Dhabi a few times,” he says, “and there were maybe 50,000 people there from Iran, Iraq, Saudi Arabia, Lebanon… incredible fans from all over the world whose countries don’t get on particularly well.” But inside that venue, he says, those fans held hands, embraced. “They’re sharing a collective musical experience”.

“If you choose to travel around the world and connect people through music, that has to be the thing that pushes you,” he says, before echoing, whether subconsciously or not, Metallica’s best-known song. “All the s*** outside… none of that matters.”

S&M2 is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments