Graceland at 35: How Paul Simon recorded a masterpiece in apartheid South Africa

Paul Simon’s album placed South African music centre stage in western culture for the first time – and would also land the musician in the eye of a political storm that would result in violence and assassination threats. Mark Beaumont explores the album’s tempestuous journey

Weekends in Soweto, South Africa, circa 1985, were the best time to be a musician. The police stayed home for a few days, so they weren’t out patrolling, following the sounds of music to unlicensed rehearsal sessions to confiscate instruments and throw them in the sea. There was no need for black artists to hide under blankets in the back of cars to get to gigs with white players in Johannesburg; the township itself came alive with music and colour. Bands struck up in every corner. Church choirs would gather in neighbours’ homes. Tribes would parade the streets singing the songs of their native tongues.

“From Zulu to Sotho to Xhosa to Shangaan…every weekend everybody dressed up with some colourful clothes,” remembers Bakithi Kumalo, a local session bassist at the time, who’d grown up learning how to mimic the tribes’ melodies on his bass. “They pass by, they sing the language and that was a good time to relax, the weekend, because there’s no government control.”

Between sessions for South African singers, recording 20 songs a day for a $5 fee, Kumalo was working as a mechanic to help buy medicine for his sick mother – one of the 16 family members sharing his four-bedroom house – when the call came from the unknown American. His boss relayed a message from his regular producer Hendrick Lebone that an out-of-towner was coming to Johannesburg for “a big project” and his playing was requested. At first, Kumalo was nervous, an almost perpetual state for the people of Soweto under apartheid.

“I’d never heard [the singer’s] name and I was scared,” he recalls. “In the township, when somebody tells you an English name, you know there’s a problem. I’m expecting a South African name calling me for a session, not an English name. My boss says, ‘Relax, he’s a singer from Jamaica’ – he sings ‘Mother and Child Reunion’. And I said, ‘That’s a brilliant song. He’s from Jamaica?’ He says, ‘No, no, Jamaica, Queens, New York’.”

Paul Simon arrived in Johannesburg in February 1985 on a pilgrimage of personal recovery and creative rejuvenation. His marriage to actor Carrie Fisher had collapsed. His turbulent on-off partnership with musical foil Art Garfunkel had hit the rocks once more, following the roaring success of their 1981 reunion concert in Central Park – the largest concert ever held at the time, before a crowd of 500,000 – and a fractious world tour. The comeback album the pair had planned fell foul of their personal differences, and emerged as Simon’s sixth solo record Hearts and Bones in 1983, his first major commercial flop. His label Warner Brothers had lost interest in him; the synthpop masses considered him a Sixties has-been. “I had a personal blow, a career setback, and the combination of the two put me into a tailspin,” he said.

In freefall, though, Simon discovered a weightless freedom. While producing a singer-songwriter called Heidi Berg, she’d handed him a label-less bootleg tape of mbaqanga street music from Soweto, entitled Gumboots: Accordion Jive, Volume Two. Already aware of the South African sounds of Ladysmith Black Mambazo, Hugh Masekela and Miriam Makeba, he was instantly entranced by this “summer music, happy music” that reminded him of the Atlantic records rhythm and blues hits of his Fifties youth. Scatting his own melodies over the tape while driving, he vowed to track down the artists, initially intending to buy the rights to the track “Gumboots” to write his own song over, as he had with his 1970 Peruvian folk single “El Condor Pasa”. Then, after hearing further tapes from South African producer Hilton Rosenthal, and with Warner paying him little attention as a lost cause, he decided to travel to Johannesburg to record with them in person. The sort of devotional odyssey which, within the confines of America, might usually have been made to Elvis Presley’s Memphis homestead.

The record he began in Johannesburg – 1986’s Graceland, 35 years old tomorrow – would become a 16 million-selling career resurrection for Simon, and a pan-global cultural benchmark. While Talking Heads, The Tom Tom Club, Adam and the Ants, Bow Wow Wow and Peter Gabriel had all explored African rhythms in their music before (the last even launching a festival, Womad, to help popularise global sounds in 1980), Graceland’s success placed South African music centre stage in mainstream western culture for the first time, and widely popularised what would become known as “world music”. It would also land Simon in the eye of a political storm that would result in violence and assassination threats and take the approval of Nelson Mandela himself to shake off.

Though Band Aid and “We Are The World” had turned many western rock superstar’s thoughts towards Africa by 1985, the prospect of one of them recording in South Africa was a moral and political minefield. Having twice turned down million-dollar offers to perform live in Sun City, Simon was well aware of the United Nations cultural boycott in place to protest the apartheid regime entering, under PW Botha, its 37th year of brutally oppressing and segregating the country’s black majority population. Consulting his friend and anti-apartheid activist Harry Belafonte following the recording of the USA For Africa single, he was reportedly advised to discuss his proposed trip with the African National Congress, who had instigated the boycott.

“In seeing Harry, he didn’t go far enough,” ANC member and Artists Against Apartheid founder Dali Tambo told NME in 1987. “He should have taken his advice, which was very solid advice. If you’re going into the country, then you must consult with the ANC… You consult with us so that we can put you wise about whether or not we think you will be used by apartheid, and about the effect of your cultural activities… If Paul Simon had come to us first and discussed this, none of this s*** would have happened.”

Instead, Simon booked two weeks of sessions at Johannesburg’s Ovation Studios without seeking any sort of approval. “I don’t feel as an artist that I have to consult with anyone,” he unapologetically explained at a 1986 press conference for the album. “I didn’t ask for permission to do the project, nor did I want any restriction on what I might think or say or write… I’m with the artists.”

“There were a bunch of other parties that were protesting, but Paul was welcome,” says Kumalo, and Simon would claim that South Africa’s black musician’s union had voted in favour of his visit. “In a way, I had to be a spokesman for the South African musical community,” he told Rolling Stone in 1985. “That is the reason I was allowed to go there … I am out there saying, ‘Take a listen to this music, world.’ That’s what they wanted me to say … I feel I owe that to them in exchange for giving me access to the musical community.” The same year, he told the New York Times: “I knew I would be criticised if I went, even though I wasn’t going to record for the government… or to perform for segregated audiences. I was following my musical instincts in wanting to work with people whose music I greatly admired.”

His critics were indeed vocal, and high-ranking. Paul Weller, Billy Bragg and The Specials’ Jerry Dammers added their voices to condemnations from Stephen Van Zandt’s Artists United Against Apartheid protest group. James Victor Ghebo, former Ghanaian ambassador to the UN, claimed “when he goes to South Africa, Paul Simon bows to apartheid. He lives in designated hotels for whites … The money he spends goes to look after white society, not to the townships.”

This wasn’t entirely true. Kumalo arrived at the Ovation Studios for the sessions, having borrowed the bus fare, to find himself working not just with a bona fide US star and his renowned producer Roy Halee but the cream of African musicians whom Rosenthal had recruited from the acts on the Gumboots tape: Lulu Masilela, General MD Shirinda and the Gaza Sisters, the Boyoyo Boys Band. What’s more, these were no $5 marathon sessions; Simon paid the musician $200 an hour, triple the New York union rate.

“I called my boss and said, ‘Listen, find somebody else, I think I’m not coming back’,” Kumalo laughs. “I got more money in one day than my boss was paying me for two or three months.”

Guided by a blind translator to allay any language barrier nerves, the sessions soon became a joy. “The whole vibe was different in the studio,” Kumalo remembers. “It was like, ‘This is a party!’ We were eating different – he would bring in sushi! Everybody was smiling, there was no stress. We got so comfortable. Paul bought me a bass and I bought clothes and then I went to the township and I looked different.” Even Halee, accustomed to more salubrious studios, was surprised by the sounds he could squeeze out of this tiny gospel garage. “I remember walking in there and thinking, ‘This is the best-sounding control room I’ve ever been in’,” he told Sound On Sound. “I’d expected a horror show, but everything worked and my first impression was, ‘This is very comfortable’.”

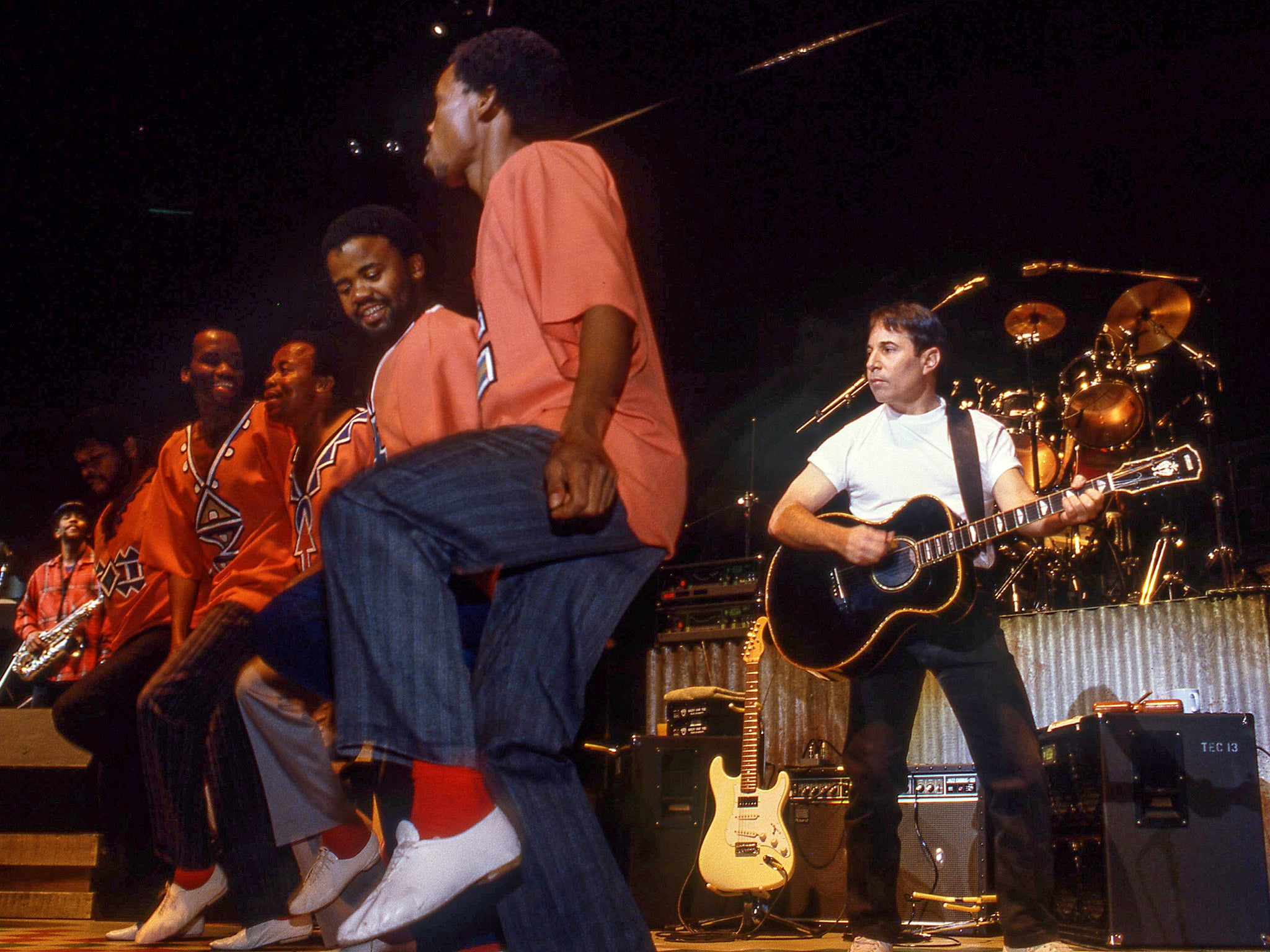

“We worked improvisationally,” Simon told the New York Times. “While a group was playing in the studio, I would sing melodies and words – anything that fit the scale they were playing in.” Simon would be accused of musical colonialism, cultural appropriation or “white saviour” exploitation over the album, but the South African musicians paint a picture of respectful, equal-footing collaboration on the series of half-hour jams worked up at Ovation.

“We used Paul as much as Paul used us,” said guitarist Ray Phiri. “There was no abuse. He came at the right time and he was what we needed to bring our music into the mainstream.”

“Paul was a godsend,” Kumalo says. “The way he treated musicians with a dignity and made us believe that you’re doing good. I was quiet most of the time, just smiling, thinking I have an engineer from America who was making my bass sound like heaven. I was in heaven! It was joyful. You can’t not be joyful in Africa when you hear this music.”

Simon, who’d arrived in Johannesburg with just a demo for “Gumboots” and left with the basis of half an album, also described the jams as “euphoric … we were functioning in a magical world, just making music. That’s what’s so great about music. It makes barriers fall away.” But the shadow of apartheid darkened even these jubilant rooms.

“There was a surface tranquility, but right below the surface there was all this tension,” Simon told Rolling Stone. “Once it gets past dark, the musicians have to figure out a way home. They couldn’t use public transportation. They are not allowed to be on the streets of Johannesburg after curfew. They would have to show papers, and it was something they clearly didn’t want to have to do. So always around six or seven o’clock, there would be an uncomfortable time when the players couldn’t concentrate until they knew there might be a car to take them home.”

Kumalo believes the difficulties he and his fellow players endured added to the urgency in their music. “My sound was something that nobody heard before,” he says. “The struggle made me really creative, play stronger. I’d play strong to get out of this struggle, I played to get out of it and it just happened. It was a great opportunity. The translator guy used to say, ‘When you have an opportunity that’s been given to you, go all the way, because it might not come back’.”

Having ventured into Soweto himself to visit a shebeen – “a gutted house where they set up a makeshift bar and have a record player and speakers … where people go to dance” – Simon returned to New York to spend several months in his Montauk home working the jams into songs: among them “Graceland”, “I Know What I Know” and “The Boy in the Bubble”, inspired by a dream he’d had about the slo-mo video footage of the Kennedy assassination while in Johannesburg. “I don’t know why I had that image,” he told Rolling Stone. “Maybe because there’s so much underlying violence going on in that country that is unspoken about.”

“When Paul and I came back to New York and listened and listened and listened to the material, it was the bass that really turned me on,” said Halee. “Take the bass line on ‘Boy in the Bubble’ – it’s off-the-wall great.” Hence Kumalo, alongside fellow South African players, found himself flown to New York for further Graceland sessions at Hit Factory Studios.

“That’s when I knew I’d made it,” he says. “I’m in a studio where the mixing board is 100 channels or something. New York was a dream place for me to go when I was about 12 years old, listening to American music – it stole my heart. I didn’t know other places in America. I thought the whole of America was in New York City.”

Playing on completed songs like “Under African Skies” and “You Can Call Me Al” was, according to Kumalo, “like opening a jar of honey – you could go forever”. Still, some of Simon’s Western pop tendencies rattled the visiting musicians. “Playing one song for nine hours...” Kumalo grins. “In Africa in nine hours you can record 10 CDs. And the minor chords, which we’re not familiar with in Africa, were like, ‘Oh my god, why is he going there? When I play that minor something is wrong, but he likes it!’”

Simon wasn’t done courting controversy yet. For the duet on “Under African Skies”, he recruited his friend Linda Ronstadt, who had accepted $500,000 to perform in Sun City in 1983. Critics likened the decision to “a slap in the face to the world anti-apartheid movement” and “using gasoline to put out birthday candles”. And when Simon tried the same collaborative methods with Los Lobos in LA for the final track “All Around the World or the Myth of Fingerprints”, the aftermath wasn’t quite as harmonious.

“He stole the song from us,” the band’s saxophone player Steve Berlin would claim, following a legal wrangle over Los Lobos’s lack of writing credit on the song. “We go into the studio, and he had quite literally nothing… no ideas, no concepts, and said, ‘Well, let’s just jam.’... Paul goes, ‘Hey, what’s that?’ We start playing what we have of it, and it is exactly what you hear on the record.”

Along with the title track’s tale of an Elvis pilgrimage to Memphis and the Cajun zydeco tune “That Was Your Mother”, recorded with Lafayette band Good Rockin’ Dopsie and the Twisters in a studio behind a record shop in Louisiana, the Los Lobos song was intended to help make the album a bridge between African and North American culture. Melting Simon’s wordy, folkish melodies into jubilant African rhythms on “I Know What I Know” and the rich, earthy vocals of Ladysmith Black Mambazo on “Homeless” (based on a traditional Zulu wedding song) and “Diamonds on the Soles of Her Shoes”, the record twinned Greenwich Village with Soweto as though they were different sides of the same town. “I wanted to say, ‘Look, don’t look upon this as something so strange and different – it actually relates to our world,’” Simon explained.

Sure enough, on its release in August 1986, Graceland charmed the globe. Its lead single, “You Can Call Me Al”, a brassy Western pop take on township jive made all the more accessible to western audiences by Chevy Chase’s comedy appearance in the video, became one of Simon’s biggest international hits; the album topped charts across Europe and Australasia and bagged a Best Album Grammy in 1987.

Anti-apartheid activists were less enthusiastic. Marking the first time that Africa’s players and voices were showcased on a mainstream American release, rather than merely its borrowed rhythms, the record found favour with the United Nations Anti-Apartheid Committee and South African campaigners such as Masekela. But the ANC blacklisted Simon and supported a boycott of his subsequent American and European tour, where protests sprung up outside venues.

Despite including imagery of police oppression in “The Boy in the Bubble” and addressing the poverty and violent displacement of South Africans in “Homeless”, Simon came under fire for focusing largely on personal lyrics of mid-life confusion on the record while failing to directly confront apartheid. “My strength is not political writing,” he argued to Rolling Stone. “I let my songs emerge from my subconscious…I didn’t say, ‘Now I’m going to write my anti-apartheid song’. I wasn’t snubbing the issue. I was investigating another area.”

The ANC boycott against Simon was lifted in 1987, but even after apartheid had crumbled and Nelson Mandela and the ANC invited Simon to play five shows at Johannesburg’s Ellis Park Stadium in 1991, Graceland still proved contentious. Hundreds of protestors besieged one concert, the office of the promoter Attie van Wyk was destroyed in a hand grenade attack, and Simon’s name was reportedly at the top of the assassination list of the militant Azanian People’s Organisation. Simon secretly met with the group to offer them proceeds from the tour in return for an assurance of the safety of himself and his audience; no deal was reached, but the shows passed without incident.

Meanwhile, Graceland was broadening music’s horizons. In the immediate aftermath of its success Ladysmith Black Mambazo became a celebrated international act, winning five Grammys, appearing in Michael Jackson’s Moonwalker and paving the way for South African acts such as Stimela and mbaqanga supergroup Mahlathini and the Mahotella Queens to wow western audiences. “World music” became the genre du jour for fellow A-listers such as Sting, and gained a reputation as the playground of wealthy cultural tourists, but once several decades had eroded such associations, it proved rich inspiration for the likes of Damon Albarn, MIA, Animal Collective and Vampire Weekend, whose self-titled debut was virtually a Graceland homage. Over the past decade, global rhythms have become fully integrated into Western music; Simon’s unifying mission was accomplished.

“What was unusual about Graceland is that it was on the surface apolitical, but what it represented was the essence of the anti-apartheid in that it was a collaboration between blacks and whites to make music that people everywhere enjoyed,” Simon told National Geographic in 2013. “It was completely the opposite from what the apartheid regime said, which is that one group of people were inferior. Here, there were no inferiors or superiors, just an acknowledgement of everybody’s work as a musician. It was a powerful statement.”

And if, in retrospect, Graceland is the sound of liberation rather than capitulation, it was a personal emancipation too. “There was the almost mystical affection and strange familiarity I felt when I first heard South African music,” Simon said. “Later, there was the visceral thrill of collaborating with South African musicians onstage. Add to this potent mix the new friendships I made with my bandmates, and the experience becomes one of the most vital in my life.”

Among those new friends was Kumalo, who moved to the US to tour with Simon for decades to come, work with the likes of Herbie Hancock, Joan Baez and Cyndi Lauper and releasing his own albums – his latest, What You Hear is What You See, arrives in October. He’s now ranked among the 50 best bassists in the world, and gratefully credits Graceland for changing his life – and, in however small a way, South Africa itself.

“That record was very important because it was the end of the era,” he argues. “Everything was about the timing. If he went in 1976 it wouldn’t have been the same. As apartheid is failing, Paul got this music and made South African music [so that] people can understand it, even from a different generation. Later on, people understood that Paul was a big part of change in South Africa because playing in Zimbabwe [at 1987’s Rufaro Soccer Stadium show in Harare, televised as The African Concert], every colour of South Africa and other parts of the world got together in one room. This had never happened. Paul came in and changed that.”

He gives a broad grin. For him, thanks to Graceland, every day is the best day to be a musician.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks