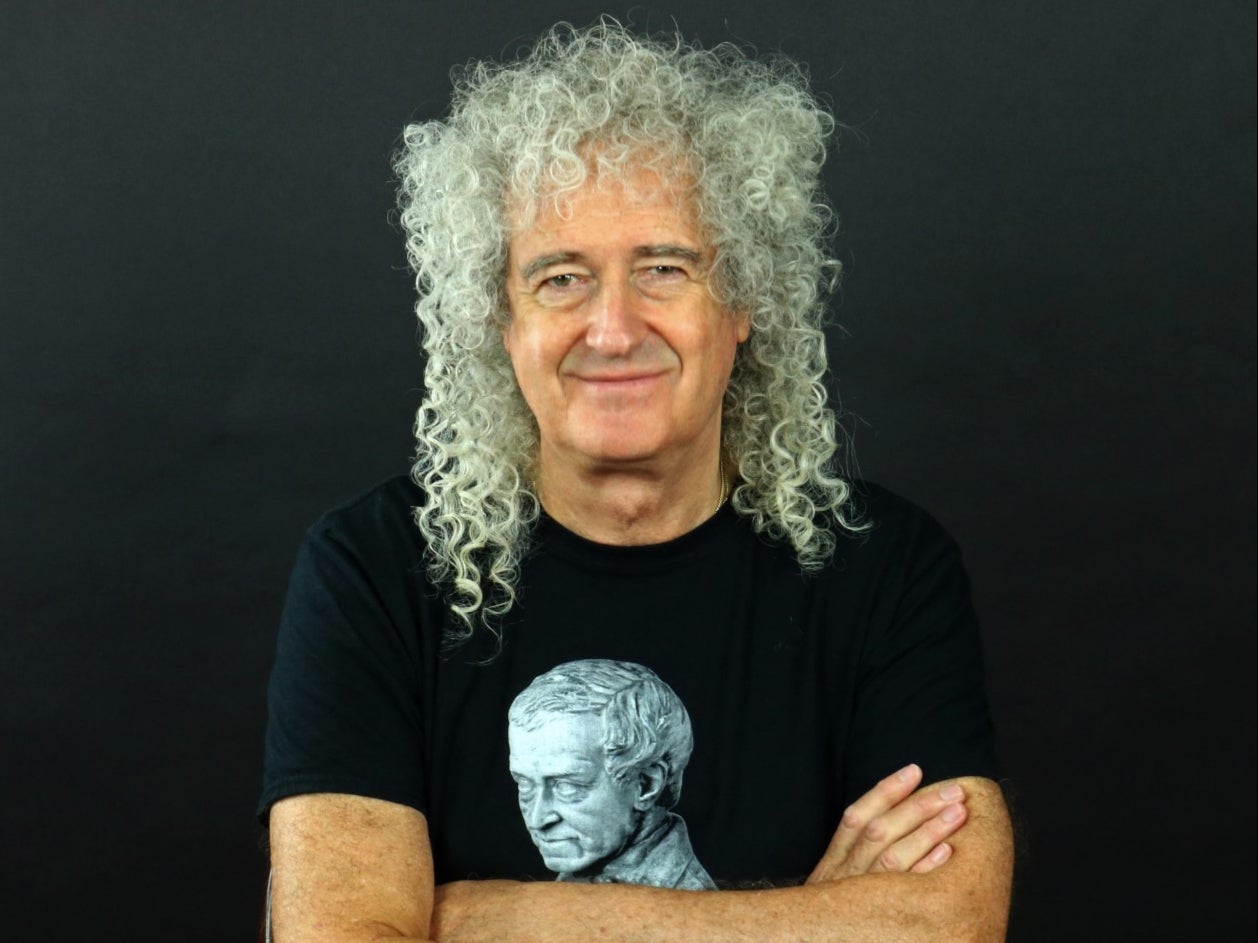

Brian May: ‘I nearly drove off Hammersmith Bridge – I couldn’t cope’

The Queen guitarist talks to Mark Beaumont about the most difficult moments of his life and why he’s resurrecting his debut solo album, as well as the Covid failures of the Johnson government, Eric Clapton and the anti-vaxxers, and why Bezos and Branson have just taken a pointless, wasteful trip

A near-death experience makes some people more focused, serene, blessed with new perspectives and thankful for second chances. Brian May’s brush with mortality, though, seems to have lit a fire. If he’s going to hang around on this earthly plane, it’s time to start demanding improvements.

“I think it would have been impossible for anyone to make worse decisions than Boris,” says Queen’s totemic guitarist – a gentle giant who ranks among the most successful musicians in history, with up to 300 million album sales and many of music’s most air-punching anthems to his name over 50 years at the very peak of British bombast rock. Speaking in hushed tones from a red-curtained Zoom screen, like an online fortune teller going rogue, he’s characteristically calm and collected but his chest – still recovering from heart surgery last year – is pumping ire.

“At every point he did too little, too late,” he says. “Hundreds, if not thousands of our relatives died because of bad advice and because of the bad decisions that Boris made with Hancock and those other people. If he’d taken the precautions of shutting down the borders a year earlier, we wouldn’t have been in the situation we were. And the fact that he’s willing to trade lives quite openly for economic gain, I find horrific… completely unacceptable. It’s like Winston Churchill going out in his garden and seeing the planes overhead and the bodies and going ‘the bombs are dropping! The bombs are dropping! Should we hide? No, actually let’s think of the economic consequences of hiding…’”

In one almost tantric opening address, May lets a year of pent-up frustrations flood out. He berates the government’s incompetent pandemic response, the media for “putting pressure on the government to do less than they were actually doing… that cost lives, I’m convinced”, Trump (“it’s easier to promulgate lies than truth these days”) and social media groupthink: “having a point of view and expressing it has become impossible. If you don’t go along with the herd view you get vilified and drummed out of business. I find it very, very unhealthy.” Before his steam runs out, he turns his sights on his long-term bugbear of badger cullers, but he saves his most withering barbs for flat-Earthers and moon landing deniers. “I don’t really want people spreading misinformation, especially if my kids are getting hold of it, or my grandchildren,” he argues. “It was all done in a Hollywood studio? Bulls***.”

May has had plenty of recuperation time over the past year to let such concerns stew to boiling point. Last May, after a bout of lockdown gardening, he suffered a heart attack requiring urgent surgery. “It was very odd. I sat down and suddenly had this tightness in the chest and a bit of a pain and the arms felt weird. I was a bit short of breath and I thought, ‘Isn’t this a heart attack?’ It’s the weirdest feeling. I was very lucky because it wasn’t a long enough episode to affect my organs or my brain critically. The day after I was in Harefield [Hospital, just outside London] having three stents put in. I came under intense pressure to have the multiple bypass surgery – when you’re lying there in bed wondering if you’re going to die tomorrow it’s the most bizarre thing, it’s like people coming in and trying to sell you encyclopaedias.”

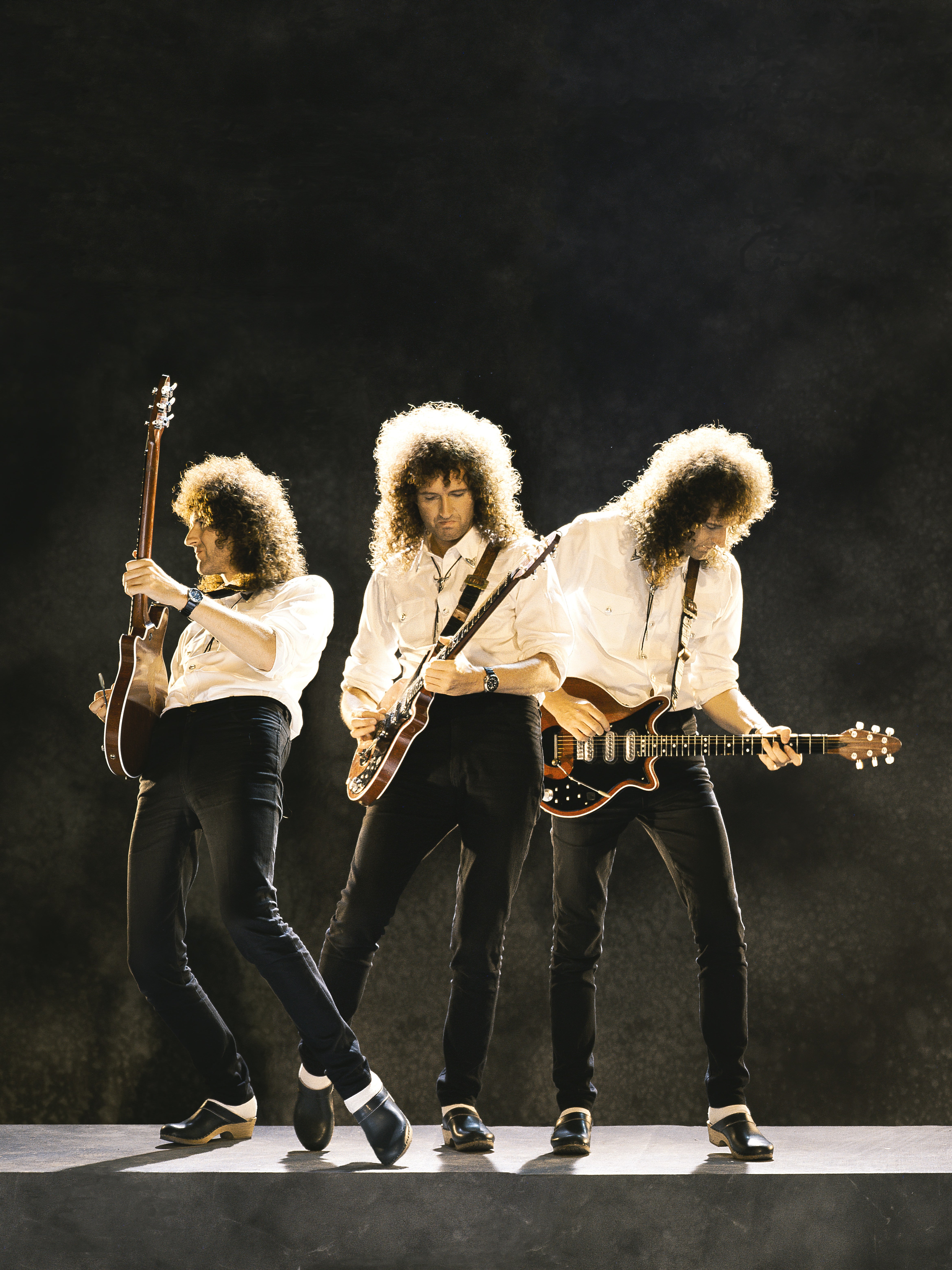

As a result, he’s become a “health and exercise addict”, undergoing cardiac rehab training: “It’s become a joy, because it really does something for your head as well as your body.” In his downtime, he also found himself reflecting on his life and career, drawn particularly to his 1992 debut solo album Back to the Light when he discovered the record wasn’t available online for him to add to his regular lockdown Instagram stories.

“I thought, ‘It’s time to do something about this,’” he says, “because I’m well proud of those albums that I made sticking out from the big edifice of Queen, at the time when Queen was looking like it was crumbling because Freddie [Mercury] was dying. It was a very, very tough time. So I thought, ‘Let's get them out.’”

Though a suitably dramatic, bombastic and Queen-like adjunct to the band’s 1991 album Innuendo, Back to the Light – re-released this week as the first in a luxuriant reissue series entitled Brian May Gold – was a deeply personal album for May, written at arguably the lowest point in his life. After he’d had two decades of overwhelming fame and success with Queen, losing Mercury to Aids in 1991 compounded the loss of his father to cancer that same year. And just as his band was falling apart, so was his first marriage.

“I was mostly very, very depressed and despondent, losing too much at one time,” he says of his mindset while making the album. “Losing Freddie, apparently losing the group, losing my marriage [May had separated from his first wife Christine Mullen in 1988], apparently losing my children, losing my dad, it was a big catalogue of loss. The stuff with my kids was the worst, feeling that I was losing them. Divorces normally get very messy and very resentful and a lot of times I was fighting to be able to see my kids. That to me was a club I didn’t want to be in and I couldn’t handle it… Something really caved in in my brain. I didn’t know what depression was in those days; I hadn’t really given it a name and I’d never sought professional help. I just wallowed around in it and tried to solve it in my own ways. I ended up nearly driving off Hammersmith Bridge a lot of times. I couldn’t cope.”

Besides his new relationship with EastEnders actress Anita Dobson, whom he’d go on to marry in 2000, it was music that kept May afloat. Writing Back to the Light “in the billiard room that I had done in the country” was a therapeutic process, producing a record steeped in loneliness, loss, pain and confusion. “Too Much Love Will Kill You” – a morbidly wry sentiment when Mercury sang it on an archive version included on Queen’s 1995 final album Made in Heaven – read like a cry for help from the pinnacle of rock’s Mount Olympus: “I’m just the shadow of the man I used to be/ And it seems like there’s no way out of this for me”. Across the record, May worked through his issues, from the rows and flying pans of break-up blues “Love Token” to “I’m Scared”, in which he primal screams a brutal torrent of fears and insecurities about death, suicide, divorce, failure, imposter syndrome, his appearance and, somewhat randomly, Steven Berkoff.

“I’m looking for everything that’s in there,” May explains, “trying to clean out all the dirt and all the fear and looking at it and kind of laughing at it, but actually facing it. It was me trying to be honest because I thought that was the way through, [to] share your feelings.”

There’s plenty of homesickness and alienation on the album too. Was he uncomfortable in the cocoon of fame? “I wasn’t uncomfortable [but] I suppose I took a while to adapt and I fiercely protected what I regarded was my real self. I didn’t want to become starry, I didn't want to become a standard rock star and I still don’t. Part of me is very much nested in science, astronomy, astrophysics [May juggled advanced astrophysics studies with music during Queen’s early years, and finally completed his long-delayed PhD in 2007]. Part of me is very much caught up in the welfare and rights of animals. I have this huge passion for stereoscopy, so I’m not really the standard rock star anyway, but I love it.”

In which case, he must have been an awkward presence at Queen’s legendarily excessive parties. “I was kind of on the fence. I enjoyed myself, I liked to party, but I’d got married just before all this happened, so I was constantly trying to tread the line and be a decent husband. It wasn’t easy, and I didn’t dive into all that stuff, like probably most people did… I don’t enjoy the feeling of the room spinning. I also didn’t take the drugs but that goes back a long way with me, it’s a kind of a commitment to myself. I wanted to keep myself clear, I wanted to know what was real. I've always been inspired by the music and I wanted it to stay that way. I didn’t want to look back in a few years’ time and it all be a jumble and I wouldn't have known what was the music and what was the drug.”

The most touching song on the record is “Nothing but Blue”, a tribute to Mercury written the day before he died. Did May have a premonition? “Yes. We knew it was close and yet we denied it in ourselves. We thought no, Freddie can’t go, it can’t happen, something has to rescue Freddie, he’s Freddie after all. How could he be allowed to slip away from us? It’s about what I thought I was going to feel when he was gone. What I actually did feel is another long story. I think both Roger and I will tell you that we over-grieved for a very long time. And by over-grieving, I mean we kind of denied that the past existed almost. We wouldn’t talk about Queen, and that went on for a while.”

Roger and I grieved for Freddie for a long time

Releasing a solo album became a key part of May’s recovery process. “I regarded myself as a musician – I think I'd resisted that, I thought maybe I was a scientist just having a little fling with music, but around that time I thought, ‘Actually, this is what I do.’ And I thought, ‘Well, I don’t have Freddie any more, I don’t have Queen any more,’ because we agreed we wouldn’t do it any more after Freddie left, or after anybody left. So I thought, ‘Well, I have to go out and do it myself. This is a door, I have to walk through it. I will be the frontman, I will sing my own stuff… I will kind of deny that Queen is important to me.’”

In the coming years, May would seek professional help at the Cottonwood clinic in Arizona, where he underwent a 12-step programme. “That’s when I actually did find out what depression was and I discovered that there was a way of treating it,” he recalls. “It was fundamentally an addiction clinic, but depression is treated as a kind of addictive behaviour there. I spent some weeks with a number of addicts, many of whom became lifelong friends. It changed my life.”

Through treatment May rediscovered his spirituality and gained strength from the Serenity Prayer – the famous text written in 1951, best known in the iteration, “God, grant me the serenity to accept the things I cannot change, courage to change the things I can, and wisdom to know the difference” – “That’s the most powerful piece of prose in the world to me – it covers just about everything that can knock you over”. Afterwards, May began to come to terms with his legacy. “The truth is, I can’t disentangle, there’s always going to be Queen in me,” he admits. “I helped to build it, I was one of the four architects. In a sense, I’m always in Queen.” It seemed only natural, then, for he and Queen drummer Roger Taylor (bassist John Deacon declined to join the reunion) to tour Queen’s ever-popular repertoire again, first with Free and Bad Company singer Paul Rodgers from 2004 until 2009, then with American Idol runner-up Adam Lambert.

“Dozens of people were ringing me up or emailing me saying, ‘You've got to hear this guy, you’ve got to get Queen back together, he’s got to be your singer,’” May says. “Then the programme actually asked us to come along and sing with the two finalists, Adam and the other guy. I think we did ‘…Champions’ and the chemistry was evident.

“Adam’s basically got everything – an extraordinary voice, an incredible range, he’s a natural performer, he’s suitably camp, which seems to be a requirement for our lead singer, he’s got a great sense of humour. He’s never tried to replace Freddie and he’s never tried to imitate Freddie. He just interprets the songs the way he feels them, so it’s not a museum piece, it’s an organic thing that’s still alive. We still have Freddie in a sense, we have little points in the show where Freddie appears… it’s a nice balance. There’s even a point where Adam can interact with Freddie in a strange way.”

May claims that the most recent Queen + Adam Lambert tour, truncated by Covid, was the biggest and most successful he has ever played, and certainly the band’s currency refuses to wane. Even after shifting 25 million copies to become the UK’s best-selling album of all time, their 1981 Greatest Hits compilation was to be found battling Olivia Rodrigo for the UK No 1 spot just last month, while recent news stories reported that Queen were making £100,000 a day from their 2018 biopic Bohemian Rhapsody. Does he even notice that sort of small change any more?

“These people don’t get their figures right,” May grins. “Bohemian Rhapsody made a billion dollars but a tiny, tiny fraction of that comes to us. It’s just the way the film industry works. We make some money out of it but not a massive amount. A lot of my money goes out towards saving animals, that’s just the way I am, I’m trying to do some good in the world… I’m conscious that I’m not particularly good at handling money, never was, but on the other hand money was never my prime thing. I was supremely happy living in a bedsit and eating cod in a bag.”

One very rich guy putting himself into space… what is it really for?

As an astrophysicist with a reported nine-figure net worth, you’d assume May would be a proud ticket holder for the Musk mission to Mars and itching to join the billionaire space race. You’d assume wrong. “I love space exploration,” he says. “I’m a member of the New Horizons team that sent a grand piano-sized object to fly by Pluto, and I interact with a lot of the Nasa missions. When it comes to one very rich guy putting himself into space – actually not into space, only about 60 miles high – I ask myself, ‘What is it really for?’ Is it blazing a trail? Not really, because men have been to the moon. Is it some kind of vanity, and if it is could the money have been better spent elsewhere? I saw this cartoon where somebody said, ‘We’ve got two billionaires competing to see who can get into space first. Wouldn’t it be nice if they competed on how quickly they could solve world hunger instead?’

“It’s kind of like being shot out of a gun and being weightless for a while. It’s not a lot different from the vomit comet, which is used to train the astronauts. I don’t think I want to do it. If someone offered me a ticket to sit up there in the International Space Station and look down on the earth for a couple of weeks I’d probably say yes, because that’s real space: what an incredible thing. I’d like to find a window that looks outwards and just contemplate the universe from that situation. I think we’re all incredibly inconsiderate to each other and our loss is huge because we don’t take care of the planet, we don’t take care of each other and we do not take care of the other species that we’re supposed to be sharing the planet with.”

Does he ever look at Professor Brian Cox making the leap from musician to celebrity scientist and think, ‘That should be me’? May laughs. “He’s amazing, incredible guy, I’ve worked with him. My group was more successful than his, but he’s a way, way better scientist than I am.”

Everybody and his conspiracist uncle on Facebook, of course, is a search engine scientist these days. May shakes his head at the mention of Ian Brown and Eric Clapton refusing to play shows with Covid restrictions and questioning the safety of the vaccines. “I love Eric Clapton, he’s my hero, but he has very different views from me in many ways. He's a person who thinks it’s OK to shoot animals for fun, so we have our disagreements, but I would never stop respecting the man. Anti-vax people, I’m sorry, I think they’re fruitcakes. There’s plenty of evidence to show that vaccination helps. On the whole they’ve been very safe. There’s always going to be some side effect in any drug you take, but to go around saying vaccines are a plot to kill you, I’m sorry, that goes in the fruitcake jar for me.”

May’s lockdown revelations have been far more personal than virological. He feels much healthier than he did before his heart attack, but little changed from the man who made Back to the Light: a scuttled, non-standard rock star determined not to go under.

“I went back and immersed myself in what I’d done in 1992 and I found that I was still that person,” he confesses. “Some of the problems are always inside yourself and they don’t necessarily go away. Your dreams, your expectations, your passions largely stay constant in your life. That’s why I still relate so much to this album. I thought, ‘This still speaks for my heart, I don’t want to change a note, I would like it out there because I’d like people to know how I feel’. Especially at this time, when we’re all looking to try to get back to the light in some way after this horrific time that all humans have been through in the last couple of years.”

He may not be Zooming from a window seat on the ISS, but his new perspective couldn’t be broader. The light is there, if humanity ever decides to bask in it.

The remastered reissue of ‘Back to the Light’ is out now

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks