Alice Cooper: ‘You could cut off your arm and eat it on stage now. The audience is shock proof’

It’s 50 years since ‘I’m Eighteen’ made a star of the rocker who prefigured the gender-fluid glam rock era. He talks to Jim Farber about his new album, what Bowie borrowed, and how, before Trump, no one thought there’d be a worse president than Nixon

Alice Cooper vividly remembers the moment when his band finally found the sound that would make them both rich and notorious. “We were playing these long, complicated songs, with jams that would go on and on,” he says. “Our song ‘I’m Eighteen’ was like that. But then our producer, Bob Ezrin, said to us, ‘dumb it down, dumb it down. This song doesn’t want to be complicated.’ Finally, when we got it dumbed down enough, it became a hit.”

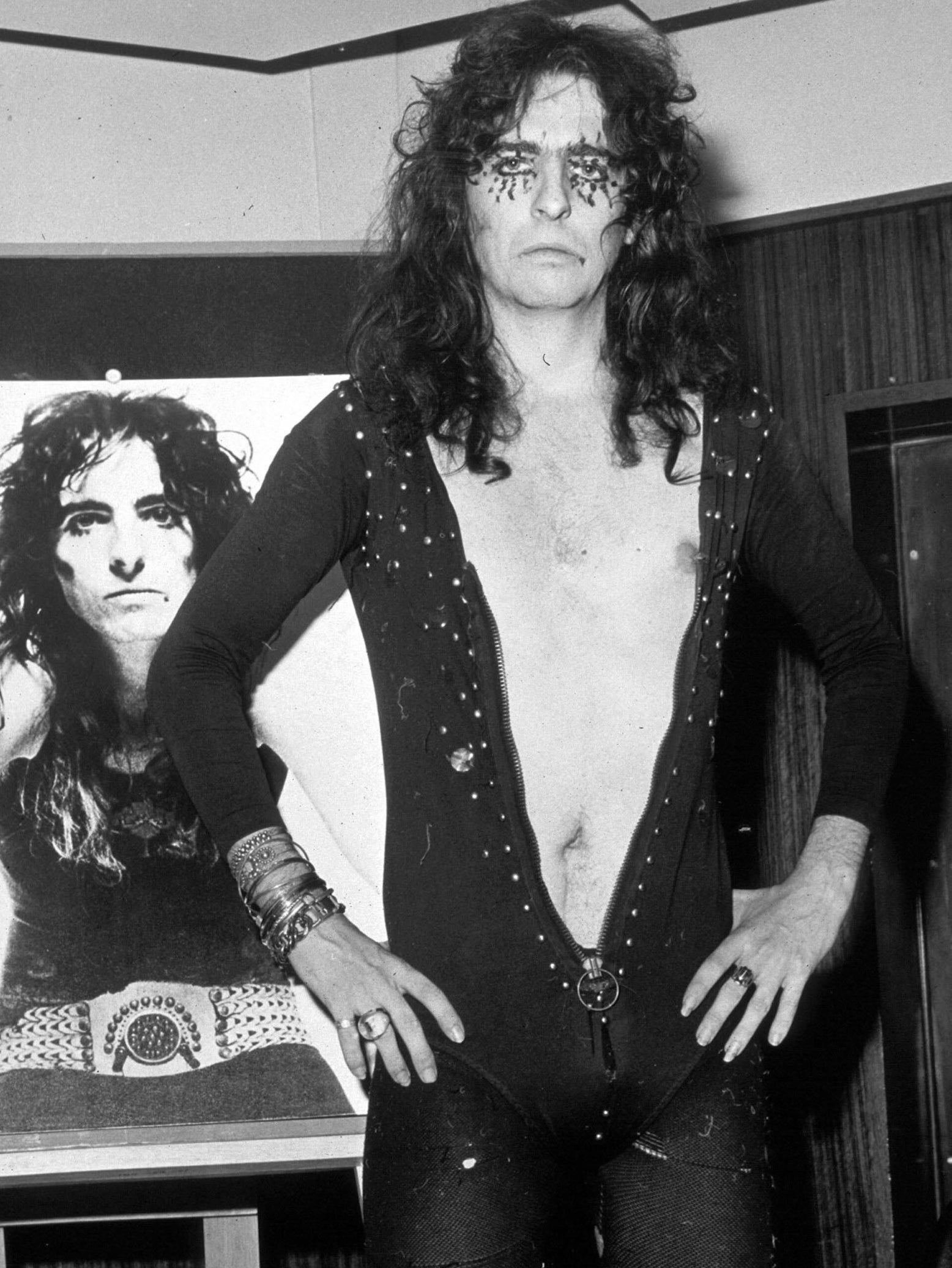

In fact, it became a big enough hit in the US to make Cooper – born Vincent Damon Furnier – a sensation, and his band one of the top acts of the 1970s. It didn’t hurt that their “dumbed down” sound – thrashing guitars mixed with a reptilian croak – slammed like a battering ram, or that it carried a teen angst theme witty and urgent enough to become a pan-generational anthem. Better, the band’s male lead singer had the headline-grabbing idea to take a woman’s name and mount the stage wearing bloodied panties over leather pants while playing around with snakes and guillotines. “We gave the audience everything their parents hated,” Cooper says with a laugh. “The way we saw it, if you’re driving by and you see Disneyland on the left side and a plane wreck on the right, you’re going to look at the plane wreck. We were that plane wreck.”

Next month will mark 50 years since it crashed, ignited by the 1971 release of the classic rock’n’roll album Love It to Death. To coincide with its anniversary, Cooper will release a new album this month that returns him to the sound and the city that inspired his breakthrough. Every song and musician on Detroit Stories honours the type of barbed-wire rock’n’roll created in that gritty American city. The album features a variety of players from seminal Motor City bands like MC5, Mitch Ryder and the Detroit Wheels, and Grand Funk Railroad, as well as all the surviving members of the original Alice Cooper Band. Cooper considers his classic group a Detroit act despite the fact that they formed in their native Phoenix and first sought fame in LA. (The singer was actually born in Detroit, but his family moved to Arizona when he was a child). “No city other than Detroit connected with what we were doing at the start,” Cooper says. “LA didn’t want anything to do with us.”

At the same time, LA’s contempt for the band helped them get their first recording contract. Frank Zappa, an Olympic-level contrarian, signed the group after watching an entire audience run for the exits minutes after they began to play. “Frank loved the freak appeal,” Cooper says.

The two Alice Cooper albums Zappa released on his Bizarre label, Pretties for You and Easy Action, were all over the place and, predictably, bombed. “We had that experimental sound, and when you put the theatre on top of it, nobody got it at all,” he says. “I think we scared the LA audience. They were mostly on acid and Alice Cooper is not what you want to see when you’re on acid.”

Searching for a new home base, their manager told them, “the first place that gives us a standing ovation, we’re going to move to”, Cooper recalls.

He thinks that turned out to be Detroit because “it’s an industrial city where they make cars so they’re always around machines that make a lot of noise. And it’s not real sophisticated. That audience wants hard rock.”

They first came to the city to play the local Saugatuck Pop Festival which also featured MC5 and Iggy and the Stooges. “I’d never heard of either of them,” Cooper says. “They were just local bands. But when I saw MC5 I thought, ‘wow.’” Then’ Iggy comes on and I went, ‘uh-oh, I got competition.’ I’d never seen anything like it. Then we did our show and it was loud and raucous and they loved it! When they found out I was born in Detroit, that was the clincher. I was the missing finger in the glove.”

The band began to record the Love It to Death album in the city, working with the then 21-year-old Ezrin, who had been an assistant on hit records by The Guess Who. (He would go on to produce everyone from Pink Floyd to U2.) “Bob hadn’t even produced an album yet,” Cooper says. “He was kinda like us, another kid. But we soon saw that this guy knows what he’s doing, and he became our George Martin. We worked every day for seven, eight hours relearning how to be Alice Cooper. Bob used to tell us, ‘when you hear Jim Morrison and the Doors, how do you know it’s them? They have a signature. You guys don’t have a signature.’ So, we worked on the sound of every instrument. Then he said to me, ‘you have a lot of different voices? What is Alice going to sound like?’ When we finally got that sound, it was Alice Cooper.”

The result highlighted how special the band were as musicians. “Mike Bruce was a great rhythm player who wrote simple songs. Dennis (Dunaway) was our surrealistic bass player. A lot of his bass lines were like a lead guitar. Neil (Smith) was like Keith Moon. He was all over those drums. And nobody played lead like Glen (Buxton). He added a lot of personality to the band.”

Meanwhile, Cooper both wrote the band’s lyrics and incarnated a character that exuded as much humour as horror. “I always thought, if you’re going to be scary, also be funny,” he says.

For extra zing, the Alice character, which he created back in 1969, presaged the gender fluidity of the entire glam rock movement. “David Bowie brought the Spiders from Mars to see our show in London,” Cooper says. “He told them, ‘that’s what we need to do.’”

Bowie downplayed the influence in later years, but it’s not hard to hear echoes of Love It to Death on The Rise and Fall of Ziggy Stardust, released more than a year later, especially in such Cooper songs as “Caught in a Dream” and “Long Way to Go”.

Following the pattern of “I’m Eighteen”, the band subsequent singles also aimed to be anthems. Their biggest chart score, “School’s Out”, which went to number one in the UK, offered an anarchic rallying cry for kids of any era. “You play that song for a 12-year-old right now and they go ‘yeah!’” Cooper says. “It’s something every kid can agree on.”

Another hit by the band, “Elected”, predicted the rise of a demagogue like Donald Trump. At that time, however – 1972 – it was written about Richard Nixon. “Nobody thought anybody would be worse than Nixon,” Cooper says with a laugh.

As the group became increasingly popular, even Bob Dylan came to acknowledge their talent. In a Rolling Stone interview in the 1970s, he shoe-horned in a line that proclaimed Cooper “an underrated songwriter”. At the same time, the road and the mounting pressures of recording took a ruinous toll on the group. Buxton’s drinking got so bad, he barely played on the band’s final album, Muscle of Love, in 1973. So, three years after they broke through, the group imploded. “We had run our race,” Cooper said. “There was nothing else we could do as that band.”

Cooper himself went straight into a successful solo career with his 1975 album, Welcome to my Nightmare. And while the rest of the group formed their own band – named Billion Dollar Babies after the hit Alice Cooper album – it tanked. During the 1990s, Cooper enjoyed a second strong run in the UK when three of his solo albums cracked the Top 10. Over the last decade, he has reunited several times with his surviving band mates. (Buxton died of viral pneumonia in 1989, after years of alcoholism.)

The new album features a track, “I Hate You”, in which each of the band members sings a verse pretending to put the other guys down. (In reality, Alice said there was never bad blood between them.) The song ends with all the guys yelling the line, “the thing we hate most is the space you left on stage,” which refers to Buxton. “Glen was our Keith Richards,” Cooper says. “He was the heart and soul of the band.”

Cooper believes the “shock rock” that launched his band could never be replicated today. “You could cut off your arm and eat it on stage and it wouldn’t matter,” he says. “The audience is shock proof.”

Yet, his snake and the music live on. At the age of 73, Cooper plans to return to the road as soon as touring becomes possible again, at which point he’ll happily belt out “I’m Eighteen” for the zillionth time. “When you sing that song in front of an audience, you are 18,” he says. “The way I look at it, Alice is like Batman or Spiderman. Those characters never age.”

‘Detroit Stories’ is out 26 February

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks