Hemingway and the pandemic: how the writer was shaped by the horrors of Spanish flu

Far from dismissing the 1918 outbreak as his macho image might suggest, the scenes that he witnessed as a young man with the Red Cross deepened his sense of human fragility, writes Eamonn O'Neill

Earlier this year, as the world came to terms with the coronavirus pandemic, a letter purporting to have been written by F Scott Fitzgerald in the midst of the 1918 flu pandemic did the rounds on the internet. It was, of course, a parody, but the writing style and notes to his pal Ernest Hemingway meant the letter – unless you’re a Fitzgerald expert – was pretty convincing.

“At this time, it seems very poignant to avoid all public spaces,” it reads. “Even the bars, as I told Hemingway, but to that he punched me in the stomach, to which I asked if he had washed his hands. He hadn’t. He is much the denier, that one. Why, he considers the virus to be just influenza. I’m curious of his sources.”

Its real author, Nick Farriella, had expertly muddied the tone of Fitzgerald’s language with some contemporary, 21st-century concerns, and a dash of the cliched image of the character we’ve come to know as “Hemingway” – something of a macho bore, brawler and liar.

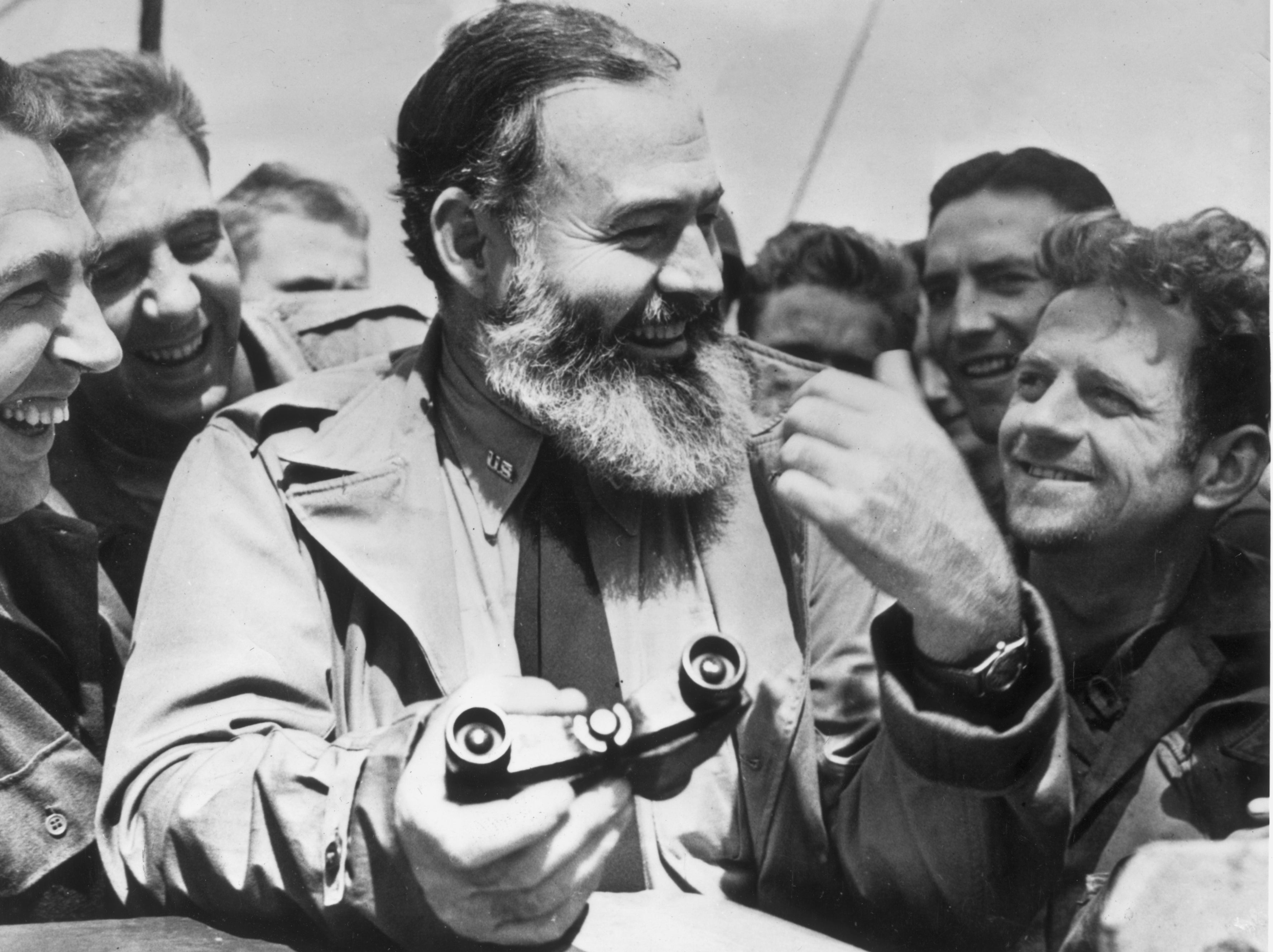

It’s an unfortunate but sometimes well-deserved persona, as I have come to know intimately whilst doing research for a new book examining Hemingway’s often ignored, shadowy time spent in London and Europe before and after D-Day.

This was an arguably defining time in his life and career, when he was possibly the best-known living writer in the world and something of a one-man global commercial brand. Even then, I discovered that when he was in the company of undercover spies and authors (sometimes both, as in the case of Roald Dahl) he could be, by turns, thoughtful, loving, brilliant, brave, embarrassing, abusive and downright nasty.

For some, the tone of the parody pandemic letter was a brief moment of entertainment because it was the return of the cartoonish wild-eyed and comical version of Hemingway from Woody Allen’s Midnight in Paris. For others, who knew a little more about Hemingway, it was yet another simplistic attempt to besmirch his deeply complex legacy – fake news, you might say.

Hemingway and the facts

In reality, Hemingway’s response to the pandemic of 1918-19 – and later waves too – was very different from the parody. The truth is effortlessly stranger and more enigmatic than any fiction. Of course, Hemingway was guilty of hyping facts to meet his mantra that fiction could be truer than the truth, but that didn’t change his basic respect for scientific facts and the natural world.

He was, after all, the dutiful son of a doctor from Oak Park, Illinois, and had witnessed first-hand his father’s work, using the experiences in his later fictional works. Hemingway scholar Susan Beegel has shown how serious illness, disease, and sudden and prolonged death were nothing new to him. He was aware, in humans and animals, of the fragility of life.

The GP’s son later had his own appalling experiences in the First World War, when he volunteered for the Red Cross. Bad eyesight meant normal duty was out of the question, but a determined Hemingway used the Red Cross to get to the Italian front line instead.

Within hours of arriving in Italy, Hemingway was tasked with cleaning up the body parts of victims of shelling, a sight that both fascinated and horrified him and which he recounted in his controversial short story A Natural History of the Dead. Within weeks he would be pulled off a battlefield himself, a bloodied wreck more dead than alive, with 228 pieces of shrapnel embedded in his legs. Long days and painful nights of touch-and-go recuperation followed.

After shadowing Red Cross nurses, Hemingway wrote about the worst death he ever saw. It hadn’t been from a bomb or a bullet: “The only natural death I've ever seen, outside of loss of blood, which isn't bad, was death from Spanish influenza. In this you drown in mucus, choking, and how you know the patient’s dead is: at the end he turns to be a little child again, though with his manly force, and fills the sheets as full as any diaper with one vast, final, yellow cataract that flows and dribbles on after he's gone.”

This horrendous scene was common amidst a global pandemic that had claimed 50 million people by December 1919. There was no coordinated national and international research as we would know it, no effective treatment, and certainly no vaccine on the way. Soldiers and volunteers like Hemingway were swimming in the virus.

Dodging disease

For a while, quarantining was all very jolly. By day, Hemingway dedicated himself to editing corrections to his soon-to-be bestseller ‘The Sun Also Rises’

Yet Hemingway dodged the peaks of the 1918-19 pandemic waves by weeks, sometimes days, as he convalesced in Italy, and then returned to the US. Once home, he discovered family and friends had perished from it. Despite youthful public insouciance, all these experiences privately scarred him, and that dying soldier in Italy was never far from his mind.

According to his masterful biographer Michael Reynolds, Hemingway’s superstition around death meant that “the slightest possibility of flu often sent him scurrying for healthier conditions, for he had a particular horror of drowning in his own fluids”. Consequently, in 1926 and now living in Paris, when his young son Jack, nicknamed “Bumby”, developed a “hacking cough”, Hemingway immediately sent him and his wife, Hadley, off to the clean air and sunshine of the Riviera to recover, while he went solo to Spain to work.

Hadley and Bumby Hemingway arrived in Antibes on 26 May 1926, and the child was immediately diagnosed with the infectious – and potentially fatal – whooping cough. Quarantine was called for, so both were summarily housed by their hosts, the ever-generous patrons of the arts Sara and Gerald Murphy, in a small dwelling near their own 14-roomed Villa America.

One week later they were moved again, under quarantine conditions, to a hastily vacated Villa Paquita at Juan-les-Pins, previously inhabited by Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, who had zipped off to the safety of another coastal retreat. To complicate matters, Hemingway’s mistress Pauline Pfeiffer, a chic editor at Vogue magazine, arrived from Paris, and within 48 hours, they were joined fresh from Madrid by the central figure in this peculiar set-up, Hemingway himself.

For a while, quarantining was all very jolly. By day, Hemingway dedicated himself to editing corrections to his soon-to-be bestseller The Sun Also Rises. By evening, everyone gathered for socially distanced cocktails with the Murphys and Fitzgeralds, who stayed outside the garden fence. Empty bottles, drained and upended, were mounted like heads on the spiked fence. Each one marked another day of quarantine for the Hemingway child.

It worked – to an extent.

Quarantine ended when his son got better, though as a precaution, Bumby and his nanny were housed nearby, leaving Hemingway in a nice hotel with the two women. He pretended he was happy, but inevitably the post-lockdown arrangement slid into emotional anarchy. He and Hadley argued, while Pfeiffer hung on for the prize she wanted most – Hemingway himself. It stayed that way as everyone decamped from the Riviera to Pamplona in Spain for the annual fiesta.

Within a year of that quarantined summer, the Hemingways were divorced.

Eleven years later, in 1937, despite quarantining in the village of Saranac Lake, in upstate New York, the Murphys’ 16-year-old son, Patrick, died from tuberculosis.

Hemingway rose at dawn on 2 July 1961 in Idaho and took his own life.

Jack Hemingway had a happier outcome than most in his family. He became a decorated Second World War veteran who survived capture and imprisonment after parachuting into Nazi Germany, and died peacefully in 2000.

Eamonn O'Neill is an associate professor in journalism at Edinburgh Napier University. This article first appeared on The Conversation.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks