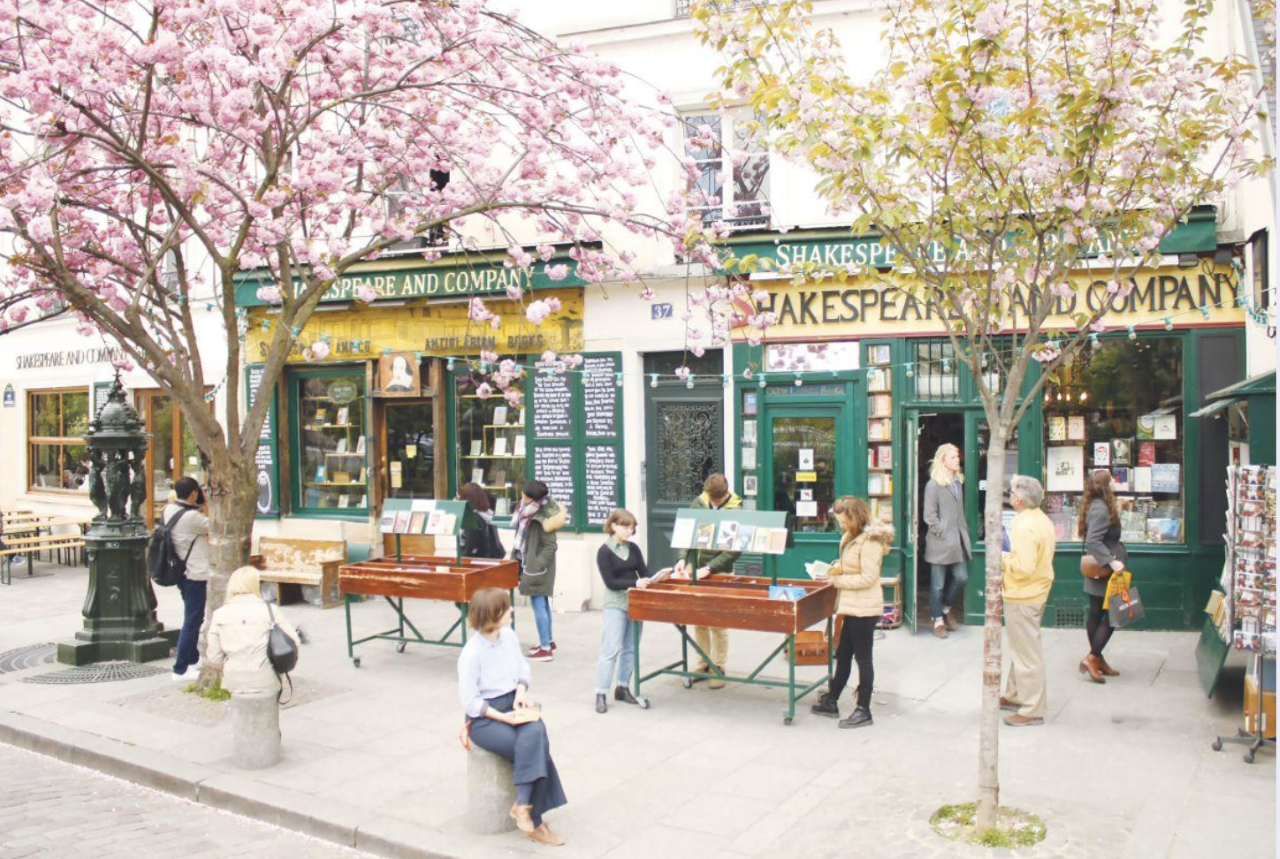

Struggling writers and ‘socialist utopia’: The story behind the ramshackle Paris bookshop beloved by Hemingway

Shakespeare and Company is now a multimillion euro business with financial benefactors all over the world, but it hasn’t lost its mystical charm, writes Peter Allen

The myth of an impoverished but magical Paris bookshop is one that has served Shakespeare and Company very well over the last century.

Its American founder, Sylvia Beach, opened the doors in 1919, and was soon handing out cash loans she could ill afford to struggling writers like James Joyce and Ernest Hemingway. There was no inside toilet, and only basic heating in cramped premises close to the Odeon Theatre. Flea market armchairs were provided for undernourished visitors to flop, talk and edit among the collapsing shelves and cockroaches.

Despite the squalor, Beach used her connections to get the first thousand copies of Joyce’s Ulysses out in time for 2 February 1922 – the author’s 40th birthday – and did not regret an outlay that threatened her with bankruptcy. She wrote in her memoirs: “It seemed natural to me that the efforts and sacrifices on my part should be proportionate to the greatness of the work I was publishing.”

Such art-above-profit determination is evoked in a new appeal for donations to support the shop into 2021: not just financially, but also “spiritually”. The idea is that you do not just pay to become a Shakespeare and Company Friend, but contribute to a near-supernatural commune, keeping it as vibrant as it ever was. Beach launched a similar membership scheme to get the shop through the Great Depression, when even established literary geniuses were facing ruin.

Today coronavirus is the great leveller – sales have been down by as much as 80 percent during lockdown – but there is a very big difference. Astonishingly, the world’s most famous small independent bookshop now has a turnover approaching €5m (£4.5m) a year, and makes very healthy profits. Accounts publicly available in France defy overblown news agency reports that it may not survive the pandemic.

In fact, so many people have been ordering on Shakespeare & Company’s website that it was forced to shut down temporarily to deal with a boom in orders. Now that the shop is open again you can turn up in person and pay as much as €25 for an edition of Ulysees and €26 for A Moveable Feast – Hemingway’s recollection of youthful penury around the very Left Bank streets where the shop is based. These are hardback prices, and come with the promise of a free shop stamp – a bonus that will very quickly turn them into collectors’ items.

All of this is a source of pride to the dynamic young management team who now run the shop with artistic passion, but also a shrewd financial acumen that pays for a full-time staff of 45, and coronavirus permitting an ambitious events programme, including visits from writers that in recent years have included Martin Amis and Rachel Cusk.

“People don’t necessarily like to think of a place as magical as Shakespeare and Company as a business concern,” said its literary director, Adam Biles, who is also an accomplished novelist. “In a way, I think they sort of like to detach this place from the general every day worries of having to make money, and buying and selling and things like that, which is interesting. There’s that famous quote: ‘The business of books is the business of life. If you’re dealing in books, if you’re making money out of books, then there’s nothing dirty or shameful about that.”

“There’s no kind of investment portfolio, or anything like that. Money is never being taken out of the bookshop – the money made by the books goes straight back into either paying salaries, or expanding the bookshop.”

Despite success with the balance sheets, the official history of Shakespeare and Company describes it as “the rag and bone shop of the heart”. George Whitman, Beach’s successor as owner, made sure the rickety stairwells at its current premises on the River Seine, opposite Notre Dame Cathedral, remained full of talent, from Samuel Beckett and Henry Miller to Beat Generation poets like Allen Ginsberg and Greg Corso.

A “Socialist utopia masquerading as a bookstore”, was George’s ultimate vision. Those seeking inspiration could share a free floor space at night with fellow “Tumbleweeds”, as he called less distinguished patrons of his literary dosshouse. One of the Beats was infamously so hard up that he used to steal books. Nobody cared too much – as long as he returned them one day.

Such anecdotes are an endless source of inspiration to Sylvia Whitman, George’s daughter, who took over as owner when he died in 2011. She too is principally motivated by her love of books, but appreciates that she is also in charge of a business on which many livelihoods depend.

“It’s not the romantic side of the story, so maybe that’s why it doesn’t interest people so much,” said Sylvia. “I do recognise that there is commercial success, because we’ve been really fortunate over the past few years to build up on the existing structure, so adding a café, a children’s room, an art room, and most recently a poetry room. We’re going from strength to strength with events, and all of that obviously takes financing, but we mainly sell books. Ninety-nine per cent of it is books.”

The Tumbleweeds remain incredibly important to Sylvia too: “The heart and soul of the bookshop comes from a lot of the writers in residence, and that just immediately gives a bohemian atmosphere. They walk about without shoes, often in love, and slightly hungover, reciting Rimbaud [the 19th century French poet Arthur Rimbaud].”

Former Tumbleweeds – there are around 30,000, many of whom have gone on to great things – have donated to the membership appeal, without wanting anything in return, while other well-to-do benefactors include France’s former socialist president, François Hollande.

Does this mean that the wishing well at the centre of the shop – where customers are invited to toss loose change in so as to “feed the starving writers” – might have outlived its historical usefulness? Not at all.

“I do feel that George’s description of a socialist utopia is still relevant,” said Sylvia. “We still have this idea that we want people to come and to be able to stay here, and almost feel like they have inherited a book lined apartment on the River Seine. You know, there is a real sense of sharing here, it’s the priority.”

Discussing the next chapter, Sylvia is cautiously optimistic: “No, we’re not about to close our doors but it depends how long the crisis goes on for, and if it goes on for many more months, we will have to get a bit smaller, but we’ll still be here.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks