It’s OK to show Woody Allen and Roman Polanski films at Cannes and Venice – if they are good

Here at the Venice Film Festival the Hollywood bad boys are out in force being feted and fawned upon despite the dark clouds of MeToo accusations hanging over them. So, asks Geoffrey McNab, are the great and the good of the film world right to look the other way?

Are European film festivals becoming the last refuges for the ageing scoundrels of the film industry? This question has occurred to many during the 80th Venice Film Festival, which closes this weekend. They are asking why directors and stars with such troublesome reputations are still finding warm receptions on the Cannes Croisette or the Venice Lido. Alleged rapists, wife batterers and child abusers are being allowed to show their movies. Festival programmers are drawing a clear distinction between these figures’ tabloid reputations and their work.

Roman Polanski is just one of several disgraced veterans who had new movies at Venice this year. He unveiled his dreadful new comedy The Palace last weekend. Joining the Polish director on the Lido was Woody Allen, presenting his French-language feature Coup de Chance, and Luc Besson, premiering his eccentric new picture, Dogman. These are all filmmakers who’ve been involved in explosive court cases relating to their private lives.

Polanski is a hugely contentious figure. Post #MeToo, there has been renewed focus on his statutory rape of teenager Samantha Geimer in the 1970s, his flight from US justice and questions over whether it’s appropriate to continue showing his work.

Allen can’t shake off the allegations of sexual abuse against him by Dylan Farrow, his adopted stepdaughter, although he continues to deny these allegations emphatically. Besson has faced a series of rape charges.

Their presence on the Lido has sharply divided opinion. To some, the criticism of these artists, which is far louder in the US and UK than in continental Europe, is evidence of hypocrisy and a disturbing rush to judgement. After all, Besson has been cleared of all the charges against him. Woody Allen again reiterated in an interview with Variety this week when asked about Farrow’s allegations, “the situation has been investigated by … two major investigative bodies. And both, after long detailed investigations, concluded there was no merit to these charges.”

It’s now 46 years since Polanski’s unlawful sexual intercourse with the then 13-year-old Samantha Geimer in 1977. He has made many films and won Oscars since then and Geimer herself has long since made her peace with him (although other women have also levelled accusations against him, which he denies).

Even when they’ve been cleared by the courts or forgiven by the victims, the filmmakers have found themselves personae non gratae at many events, especially those in the UK or North America. It was very telling that none of the films by Besson, Polanski and Allen was selected for the Toronto or London Film Festivals (which generally programme high-profile titles from the Lido).

The European festivals remain far more accommodating. Even when there has been substance to the allegations against filmmakers and actors, the invitations haven’t been withdrawn. Johnny Depp has faced conflicting libel judgments first in the UK, where he lost his case against The Sun, which had labelled him a wife beater, and then in the US, where he won after his ex-wife Amber Heard was ordered to compensate him for defamation. Nonetheless, in spite of the controversy still surrounding him, he remains the face of French fashion house Dior’s Sauvage scent and continues to be invited to illustrious film events such as Cannes and San Sebastian.

Depp gave an intriguing performance, dark and introspective, as Louis XV of France, in actor-director Maïwenn’s lavish costume drama Jeanne du Barry, which opened Cannes in May, and yet many took exception to his being there at all. He travelled to the Riviera in the wake of his bitter divorce from Heard, amid those continuing accusations of domestic abuse. Festival director Thierry Fremaux batted away concerns, pointing out that no one had banned Depp from acting in a movie. If they had done, “we wouldn’t be here talking about it [his new film]”.

Asked recently by The Independent about Depp’s fall from grace, his regular collaborator, Ed Wood director Tim Burton likened the morally indignant online vigilantes targeting Depp to the angry villagers in Frankenstein. “I always used to think about society that way, as the angry village,” he said. “You see it more and more. It’s a very, very strange human dynamic, a human trait that I don’t quite like or understand.”

Like Fremaux in Cannes, the Venice festival’s director Alberto Barbera hasn’t been remotely apologetic about hosting figures whose names come with sizeable asterisks next to them. “I’m not a judge who is asked to make a judgment about the bad behaviour of someone. I’m a film critic, my job is judging the quality of his films,” he told The Guardian.

Weinstein has faded from view. The same can’t be said of Polanski, Allen and Besson. These filmmakers remain lightning rods

The obvious counterargument is that giving artists such as Polanski a platform at festivals is to endorse alleged or actual misbehaviour and abuse of power. It is to risk undermining the work of the #MeToo and #OscarsSoWhite movements in shifting long-entrenched attitudes within the industry. What is the point in all the talk about diversity and gender equality if those accused of serious wrongdoing are still being feted today?

The imprisoned Weinstein has faded from view. The same can’t be said of Polanski and Allen. These filmmakers remain lightning rods. In Venice this week, they have posed troublesome questions for audiences, fans and critics alike.

It was startling to see the contrast between the sunny mood of reviewers coming out of Monday morning’s press screening of the new Woody Allen film and the rage of protesters later in the day outside the premiere. The former were pleasantly surprised by the wit, humour and emotional depth of Coup de Chance. The latter howled at the director with undisguised contempt and fury.

Polanski and Allen are being forced to work with European financiers because no Americans will go near them. Certain commentators imply that the European industry is far more laissez-faire about morality than those upright US studio folk who simply won’t associate themselves with the now tarnished idols. This idea is palpably absurd. I remember years ago interviewing the actor Nick Nolte not long after he had been arrested for driving drunkenly down the Pacific Coast Highway. He had had his mugshot taken by the cops. His dishevelled appearance and garish Hawaiian shirt made headlines around the world. Was he worried his career might be affected adversely? Not at all, he blithely replied. If it wasn’t “kiddy porn and you haven’t murdered anyone”, the studios didn’t mind what you did as long as you could still make them money.

When Amazon Studios cancelled its film deal with Allen in 2019, the streaming giant claimed that his reputation and comments had made it impossible to market his films properly. The subtext there was that he was no longer bankable. This was a fiscal decision as much as it was a moral one.

What is becoming increasingly apparent is the inconsistency and irrationality on both sides of the debate about which filmmakers should be cancelled and why. Allen, Polanski and Besson are far from the only directors who have faced serious claims of misconduct. Another film screening in Venice this week, Matthew Wells’s documentary Frank Capra: Mr America, revealed that the Italian-American filmmaker behind everyone’s favourite Christmas movie, It’s a Wonderful Life (1946), was, in fact, a racist who insulted almost every ethnic group imaginable including his own. Should he be cancelled too or only allowed to have films shown at festivals?

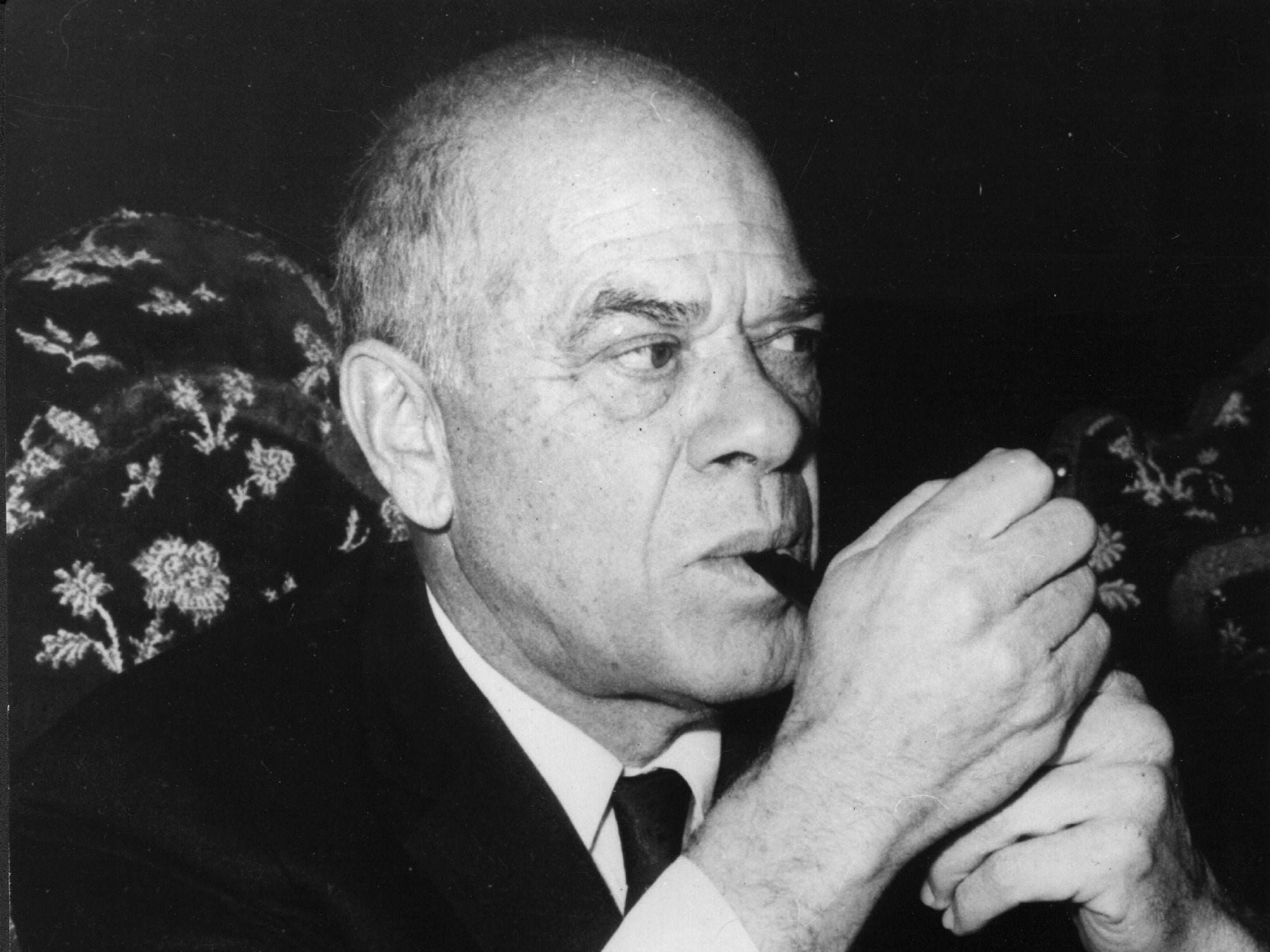

What about Otto Preminger, who was a notorious sadist, or John Ford, a mean-spirited bully whose behaviour on set would surely not be tolerated today, or Hitchcock, with his coercive abuse and harassment of Tippi Hedren, or Michael Powell, notorious for browbeating crew members, or Ingmar Bergman, whose tantrums were legendary, or Bernardo Bertolucci’s shameful treatment of the young Maria Schneider during the making of Last Tango in Paris (1972)? The list goes on and on. If you were going to be truly consistent in dealing with claims of bad behaviour and objectionable attitudes, you’d probably have to cancel at least half the filmmakers in cinema history, starting with DW Griffith for his unabated racism and going up to such contemporary figures as Brett Ratner, who has faced multiple accusations of sexual misconduct (accusations he’s vehemently denied). At the same time, it seems craven not to call filmmakers out when they harass, intimidate, assault or prey on colleagues, friends and family.

Surely some balance and perspective is now needed? There have been hugely positive changes in the European and US film industries over the past five years. The membership of Ampas (Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences), the Oscar-voting organisation, is now far more diverse and international than when Spike Lee snubbed the event in 2016 because of its almost all-white lists of nominees.

Austrian director Jessica Hausner (whose new British-set feature Club Zero premiered in Cannes) talked recently about how the rampantly chauvinistic attitudes she encountered earlier in her career are no longer tolerated in the European industry. “The whole #MeToo movement has challenged us all and has shown us that this patriarchy exists. We nearly had forgotten… I was living in a world where I decided to accept it. But then came #MeToo and I decide maybe I don’t have to accept it, I don’t have to live with it. To me, this #MeToo movement really was an eye-opener. It changed a lot.”

No one wants the changes overturned but it should still be permissible for Cannes and Venice to show films by the likes of Polanski, Besson and Allen if that work is strong enough. The alternative is for those festivals to fall down a rabbit hole of extreme political correctness in which programmers are no longer judging the work on its own merits but are instead assessing every new film on the basis of the tortuous backstories of those who made it.

On aesthetic grounds alone, it would surely have been far wiser for Venice head Barbera to drop the reels from Polanski’s The Palace, probably the worst film the Pole has ever made, into the Venice lagoon than actually to project it in public. Critics savaged it with a ferocity that made the behaviour of the killer pooches in Besson’s bizarre canine thriller Dogman look mild by comparison. At least, though, for once, they were attacking the film and not launching an ad hominem assault on the man who made it.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks