Macho Mann: The Hollywood director who still loves a cold-hearted killer

In movies like ‘Heat’, ‘Thief’ and ‘The Last of the Mohicans’, filmmaker Michael Mann perfected the art of digging into the souls of fatalistic men. As the director’s biopic of Italian entrepreneur Enzo Ferrari hits the Venice Film Festival, Geoffrey Macnab salutes his career so far

There is a cult of macho individualism that certain movie directors can’t seem to shrug off, whatever their age. Michael Mann is one such director. “Have no attachments. Allow nothing in your life that you cannot walk out on in 30 seconds flat if you spot the heat around the corner.” So goes the philosophy of master thief Neil McCauley (Robert De Niro) in Mann’s epic crime thriller Heat (1995). While it is among the most memorable lines of Nineties action cinema, the words would be equally believable uttered from the lips of John Wayne as vigilante Ethan Edwards in John Ford’s The Searchers (1956), the lone cowboy “doomed to wander between the winds” as Martin Scorsese once described him.

Cary Grant’s Geoff, the air freight boss in a remote South American outpost in Howard Hawks’ Only Angels Have Wings (1939) is another character cut from the same hardy cloth. “Joe died flying, didn’t he? That was his job. He just wasn’t good enough,” Geoff reacts after yet another of his young pilots, and close friend of his, is killed in the mist. Emotional attachment is a serious no-go for these men.

For better or worse, Mann is unreconstructed in his view of masculinity. The heroes of his films, who are always men, are defined by their professionalism and their ruthlessness. They don’t crumble in a crisis and they seldom give vent to their feelings.

The veteran US director will be in Venice later this month with his new movie, Ferrari, about the Italian motor racing maestro and businessman, Enzo Ferrari (played by Adam Driver). Advance word suggests that Enzo is yet another of cinema’s rugged, lonesome heroes, a Mann’s man doing what a man has to do. Penelope Cruz plays his wife, Laura Ferrari, and Shailene Woodley is his mistress, Lina Lardi. The film is set during a short and turbulent period of its subject’s life, long after he had retired from racing cars in order to start building them. Enzo’s factory is teetering near bankruptcy. His son has recently died, and his marriage is on the ropes. At this point, Enzo risks it all – his family and his reputation – on a bet that he can win the 1957 Mille Miglia, the 1,000-mile race between Brescia and Rome over public roads involving over 300 cars, as celebrated as it was lethal.

“Open-road races had long been considered too dangerous by most civilised nations,” author Brock Yates wrote in his 1991 book, Enzo Ferrari: The Man and the Machine, from which Mann’s movie is drawn. The Italians loved the Mille Miglia. As many as 10 million people would line up every year to watch “fast cars racing on real roads, around twisting mountain hairpins and through narrow city streets”.

In 1957, the bet paid off. Sort of. Ferrari triumphed with driver Pierro Taruffi (played in the film by Patrick Dempsey, a real-life race car driver as well as an actor) coming in first place. Tragically, however, another competitor in a Ferrari car, Spanish aristocrat, gambler and playboy Alfonso De Portago (Gabriel Leone), was killed after his tyre burst. He had been photographed shortly before the accident, on a brief stop during the race, kissing the movie star Linda Christian (played by Sarah Gadon). His car spun out of control, like “a pinwheel of death” in Yates’ account, and hit the crowd. Twelve people were killed including five children and Portago himself – who was “sawn in half by the scything hood of the Ferrari”.

Enzo secured the victory he craved but paid a heavy price. “Death had wrapped itself around Enzo Ferrari like a Modena winter fog,” Yates writes evocatively in his book. The press came after him. The Vatican thundered that motorsports were immoral. He was charged with manslaughter. Although (as Yates notes), it was “silly and irrelevant” to blame the constructor for the carnage, it took Enzo over four years to clear his name.

This, then, promises to be an enthralling story of a captivating man. In his dark glasses and sleek suits, Enzo looked as much like a Mafioso as he did an automobile magnate. Ferrari’s own website celebrates what it calls the founder’s “ruthless single-mindedness”. You can easily understand why Mann was so drawn to him as a subject.

“It’s a very intense story which only takes place over four months, but it is the pivotal four months of his [Enzo’s] life, in 1957,” the director (also an executive producer on 2019’s Ford vs Ferrari) told USA Today News before he started work on the project. “So, it’s very much a drama. I am not interested in linear biopics that try to encapsulate a whole life.” Elsewhere, he has described the movie as an “operatic melodrama in real life”. The new picture has taken as long to construct as any of its subject’s most cherished cars. It was scripted by the late British writer Troy Kennedy Martin (best known as the creator of TV’s cop series Z Cars and writer of the Michael Caine movie The Italian Job). It fits neatly into Mann’s tradition of testosterone-driven, detail-oriented studies of a lone hero – a winning formula the Chicago-born director has returned to again and again.

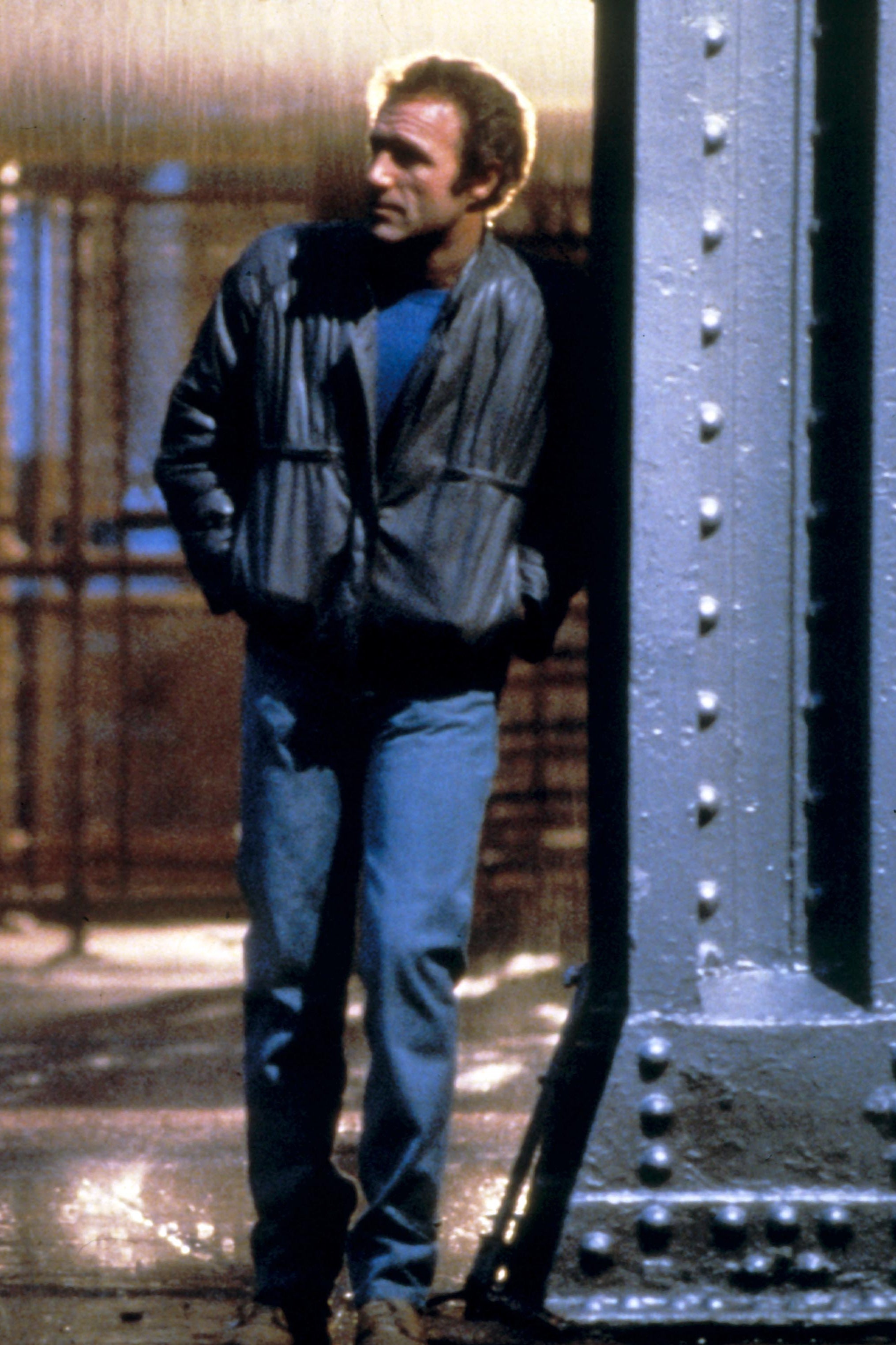

In his debut theatrical feature, Thief (1981), the main character shared traits with both Ferrari and De Niro’s Neil McCauley. The safe-breaker Frank (James Caan) is equally resourceful and self-reliant. He has Ferrari’s fascination with machinery and, like Neil McCauley, he has done time in jail. “I don’t care about nothing but myself… I survived because I achieved that mental attitude,” Frank tells the waitress (Tuesday Weld) he becomes involved with. “You don’t know from one day to the next whether you’re going to get killed, go home or get busted,” she says to him – a piece of advice that would serve almost any of Mann’s protagonists similarly well.

Mann’s brand of macho action cinema has deep roots. Gangster films and westerns are full of characters who ride alone and die alone, more often than not in a bloody crash or in a hailstorm of bullets. They are professionals with a grimly fatalistic view of life. They don’t complain when luck turns against them. Today these anti-heroes, almost always men, can’t help but seem strangely anachronistic. In cinema as in society, masculinity is no longer defined by how quickly and efficiently you can blow a safe or shoot your enemies between the eyes. Shedding a tear or showing doubt is no longer taboo either.

Profiles of Mann invariably caricature him as being just like one of the emotionally aloof, ferociously driven characters of his movies. The New York Times, last year, recalled him on the set of Ferrari agonising over the colour of the wallpaper in Laura Ferrari’s room. Daniel Day-Lewis (who starred in Mann’s 1992 film The Last of the Mohicans) was quoted as describing the director as “an intellectual, but he thinks like an engineer, and he has the spirit of an artist”. It makes him sound like Howard Roark, the maverick architect hero who ends up dynamiting his own building in the absurdly overblown 1949 movie adaptation of Ayn Rand’s The Fountainhead starring Gary Cooper.

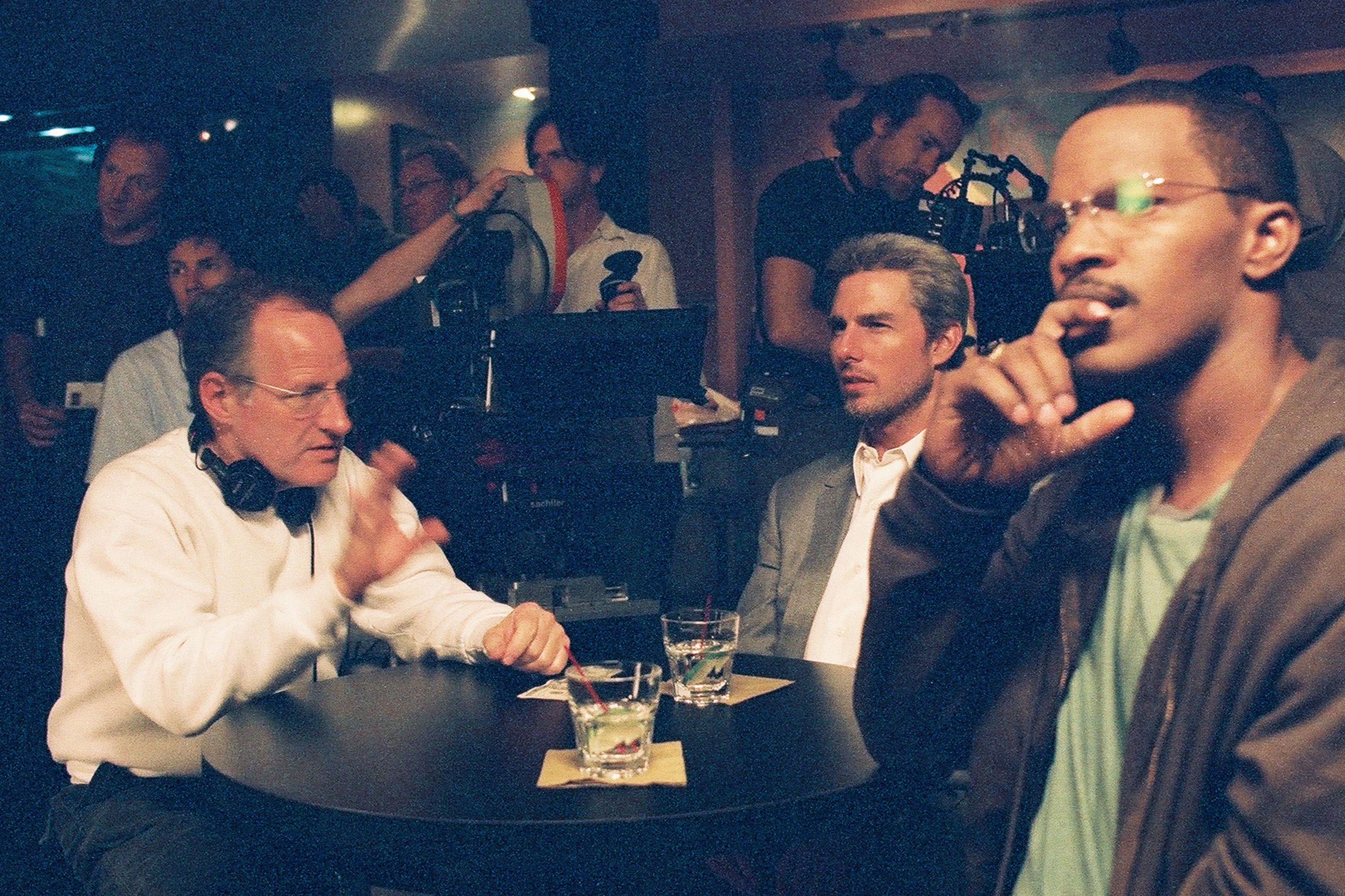

Rand’s cult of extreme individualism has been endorsed by everybody from Donald Trump to Oliver Stone. “Rand lionises the alpha male capitalist entrepreneur, the man of action who towers over the little people and the pettifogging bureaucrats – and gets things done,” author Jonathan Freedland wrote in an attempt to sum up why Rand’s novels remain so popular. Mann’s movies do something similar. Their heroes, whether the assassin played by Tom Cruise in Collateral (2004), De Niro’s criminal in Heat, Day-Lewis’s pathfinder in the Mohicans movie, Will Smith’s heavyweight champ in Ali (2001) or now Adam Driver’s Ferrari, are always headstrong mavericks going their own way.

As they grow older, other directors who, like Mann, had specialised in making visceral action movies about lone wolves, have reconsidered their priorities. Late Howard Hawks films became notably more playful. In Hatari (1962), his laidback screwball safari comedy filmed in Tanzania, Hawks cast John Wayne opposite scene-stealing baby elephants and monkeys. “I wanted to make it like it was a vacation,” the director later said of the film’s easygoing, tongue-in-cheek mood. Toward the end of his life, Japanese master Akira Kurosawa moved away from samurai stories and towards comedies like Madadadyo (1993), reflective dramas like Rhapsody in August (1991), one of few films he made featuring a female lead, about an old woman who lost her husband in the Nagasaki bombing, and his introspective portmanteau picture Dreams (1990). At 80, resisting this late career trend, Mann isn’t toning down the machismo in the slightest. Last year, he published his first novel, a sequel to Heat which he hopes to make into a film (possibly with Adam Driver taking over De Niro’s role as Neil McCauley). Now he is set to unleash Ferrari.

The early responses to the new movie have been glowing. “Mann has made many remarkable movies but perhaps never one as simultaneously thrilling and moving… Not just a feat of virtuosity, this is a grand and striking evolution of his career themes and his most deeply personal work,” critic and programmer Dennis Lim commented after announcing that Ferrari would close this year’s New York Film Festival. These are lofty words, and it remains to be seen if the new film will indeed harness the raw power of its predecessors. After all, even the most alpha male movie directors lose their thrust sooner or later. There will come a moment when they spot the heat coming around the corner – and realise they are simply too frail to get away.

Michael Mann’s ‘Ferrari’ screens in competition at the 80th Venice Film Festival next month

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks