Oppenheimer and the cult of the Brainy Blockbuster

As Christopher Nolan’s historical biopic storms the box office, Geoffrey Macnab explores the films that found commercial success while still challenging audiences intellectually

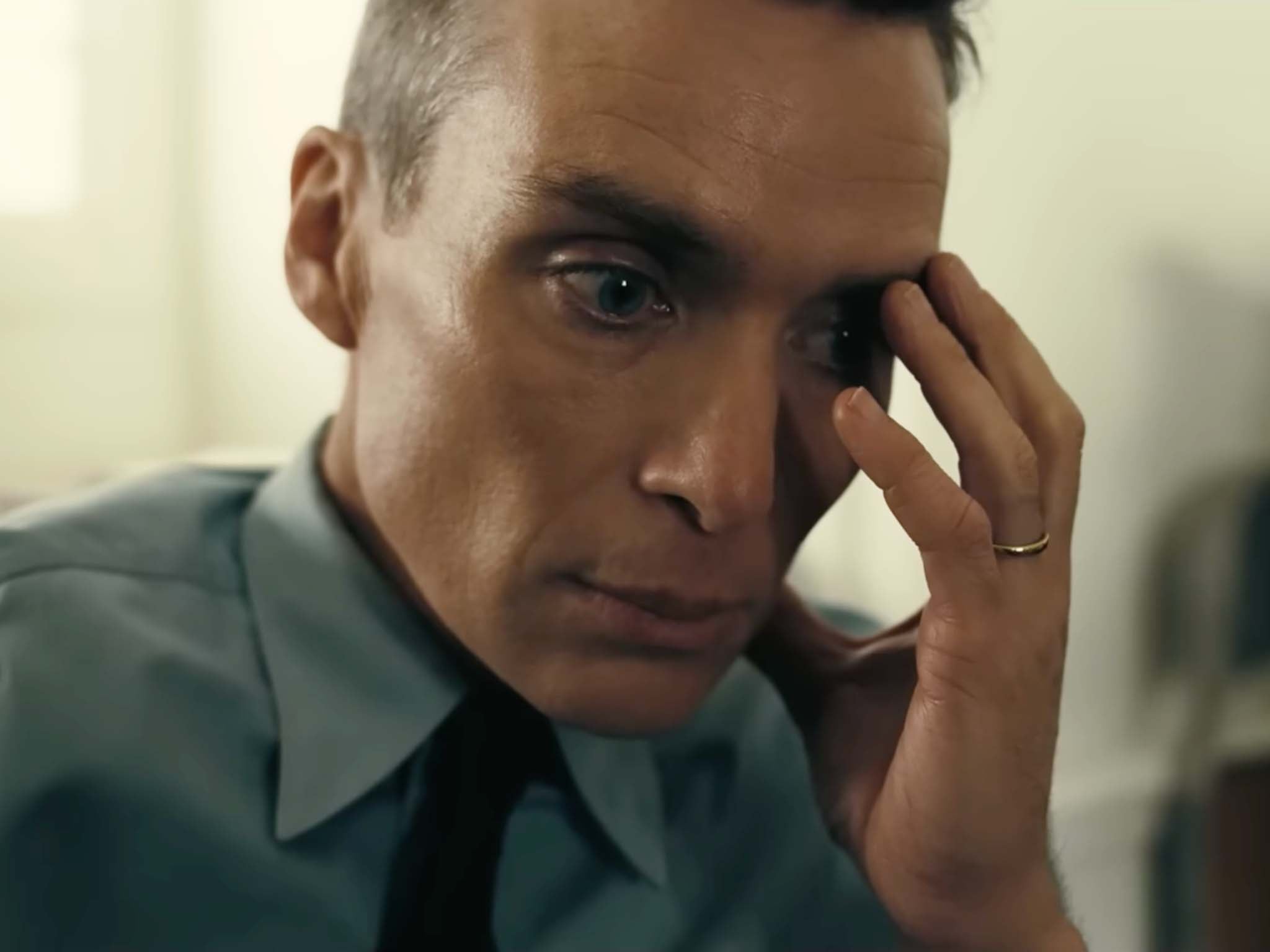

Cillian Murphy, star of current box office hit Oppenheimer, recently explained how he had known all along that Christopher Nolan’s cerebral new feature would connect with audiences. “It is, thematically, so huge. All the questions it poses, these huge ethical, moral paradoxes. It’s kind of massive…” the actor told host Marc Maron on the WTF podcast. “I love the way he [Nolan] presupposes a level of intelligence in the audience. He knows the audiences aren’t dummies and he knows the audience can keep up. He knows the audience wants to be provoked and challenged.”

Indeed, Oppenheimer makes heavy demands on viewers. It is a biopic of the theoretical physicist who led the US efforts in building the first atomic bomb. Shot in 70mm, the film features spectacular and disturbing sequences of nuclear blasts, but any action is contained within 10 minutes of its three-hour runtime. Much of the drama instead involves scientists, politicians and military personnel in labs, offices and courtrooms, talking and talking. This, then, is not Iron Man or Star Wars – yet Oppenheimer has made over $200m globally in ticket sales during the first four days of release, a staggering figure rarely achieved outside franchise epics and Marvel movies.

There is a long tradition of artistically complex films winning Best Picture Oscars but, as was the case with Everything Everywhere All at Once (2022), Coda (2021) and Nomadland (2020), these tend to be made on relatively small budgets, certainly not with the $100m pot Nolan reportedly dipped into for Oppenheimer. Their box office returns were modest, too. When it comes to commissioning blockbusters, Hollywood studio executives are generally thought to have a very low opinion of their customers’ intelligence. And they are far more interested in getting a return on their investment than they are in wrestling with big ideas about politics, war, communism, and nuclear fission. The result is what Martin Scorsese has disparagingly referred to as “theme park” cinema: popcorn movies for distracted viewers in which superheroes save the world, dinosaurs run amok, sharks snack on surfers, and intrepid astronauts travel to galaxies far, far away.

That’s why, at first glance, it seems such a surprise that Nolan was allowed to embark on a project as ambitious and eggheaded as Oppenheimer. But the fact is, if you look over film history, you’ll quickly realise that alongside the so-called “high concept” movies – the brash, VFX-driven action-dramas whose plots can be summed up on the back of a small envelope and which any producer can pitch in 30 seconds – Hollywood has often produced far more challenging work and has sometimes done very well with it, financially speaking. Contrary to popular belief, the biggest earners aren’t always the franchise films. Look at the Box Office Mojo charts for “Top Lifetime Adjusted Grosses” and you’ll find plenty of left-field work. Long before Oppenheimer, the US majors were achieving blockbuster results with highbrow, subversive movies.

From today’s vantage point, it seems astonishing that an English-language screen adaptation of a once-banned book by a Russian poet and philosopher was seen in cinemas by significantly more people than watched either Avatar (2009) or Avengers: Endgame (2019). David Lean’s 1965 screen version of Boris Pasternak’s Doctor Zhivago, starring Omar Sharif as a sensitive doctor caught up in the tumultuous events of the First World War and the Russian Revolution, sold an estimated 124 million tickets worldwide. It’s almost as many as the 128 million haul achieved a decade later by Steven Spielberg’s Jaws (1975), the movie now credited with ushering in the new age of summer tentpoles.

Like Oppenheimer, Doctor Zhivago was three hours long. It had an equally intricate narrative structure involving flashbacks, jumps in time, and a storyline dealing with political upheaval. It opened with an absurdly lengthy musical overture in which spectators heard Maurice Jarre’s Oscar-winning score as they looked on at abstract, wallpaper-style imagery of trees for several minutes. Lean recreated the wintry Soviet Union in a sweltering studio in Madrid. The film had a love story at its core but the ultimately doomed romance between Sharif’s Yuri Zhivago and the beautiful young Lara (Julie Christie) aside, it has many similarities with Oppenheimer. Reviews for Doctor Zhivago, however, were far more grudging than they have been for Nolan’s biopic. It was dismissed as “a spectacular soap opera filled with cardboard characters” and derided as irredeemably pretentious – yet still, it was a huge hit wherever it showed. “It seemed that nobody liked it but the public,” Lean’s biographer Gene D Phillips later quipped.

Zhivago demonstrated that an auteur-driven literary adaptation with highbrow credentials could do well among mass audiences. In hindsight, the box office success of William Friedkin’s The Exorcist (1973) was even more surprising than that of Zhivago or of Oppenheimer. With its vomiting, head-twisting and masturbating with a crucifix, Friedkin’s shocker looked guaranteed to alienate and disgust any mainstream audience. Instead, this story about a seemingly happy, healthy girl (Linda Blair) possessed by the devil turned into the highest-grossing X-rated film in history. Still today, it remains one of Warner Bros’ biggest success stories. And while The Exorcist may be a horror movie, it is a complex one that explores religion and faith at the same time as it scares viewers witless.

Like Oppenheimer and Barbie, its pink-hued summer box office rival, The Exorcist became a full-blown cultural phenomenon. When it reached London cinemas in the spring of 1974, venue managers were startled to see thousands of people queuing around the block early on the morning it opened. It was later banned in certain towns (including Wakefield) and reports, which emerged in papers like the Liverpool Echo, of St John Ambulance men doing “brisk business reviving casualties of fainting, hysteria and sickness” wherever The Exorcist showed only whetted the public’s curiosity further.

Today, The Exorcist is acknowledged as a classic. “A masterpiece of not just horror film” is how it is described by the Venice Film Festival, where next month a screening will be shown to commemorate its 50th anniversary. What the festival organisers don’t mention is the blockbuster status of The Exorcist, a film that (according to Box Office Mojo estimates) sold more tickets than Jurassic Park, Marvel or any James Bond outing. Jason Blum’s Exorcist sequels (the first of which, The Exorcist: Believer is due in the autumn) will struggle to emulate its success.

It’s not only subversive horror films that have done jaw-dropping levels of box office business, but offbeat romantic dramas, too. Who needs Superman or Batman when you can have Benjamin Braddock? The Graduate (1967) was adapted by Mike Nichols from a short literary novel by Charles Webb. It starred Dustin Hoffman as Benjamin, a neurotic young college graduate drifting through life when he is seduced by an older woman (Anne Bancroft’s Mrs Robinson). The Graduate was a risqué suburban satire in which the most memorable character was an alcoholic, middle-aged seductress – and somehow it achieved global ticket sales of 85 million. The Simon and Garfunkel songs may have helped but the film’s runaway success still took everyone by surprise. Nichols thought he had made a barbed, small-scale art movie, which would do only modest business at best.

Critically, the film fared less well, at least at first. The director’s biographer Mark Harris wrote: “The first people who saw the movie had only derogatory things to say about Hoffman.” Critic Pauline Kael likened it to a television commercial. Cast members themselves were underwhelmed by their own work. It was only when the filmmakers attended a public preview and saw the young audience whooping and hollering at the end, when Benjamin elopes with Mrs Robinson’s daughter Elaine (Katharine Ross), that they realised they had made a hit. Currently, The Graduate sits at number 23 on the all-time box office, just below Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).

The late 1960s and 1970s offered up many of the most offbeat hits in movie history. There are obvious reasons: the counterculture, the end of the old-style studio system, and the willingness of Hollywood execs to back unusual, irreverent projects from fearless young directors – but even so, you don’t expect to see Robert Altman’s freewheeling, semi-improvised Korean War satire M*A*S*H (1970) selling more tickets than Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1984), or that the adjusted grosses for Milos Forman’s One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), featuring Jack Nicholson as the rebellious inmate in a mental asylum, were higher than those for Pixar’s Toy Story 3 (2010). Such results suggest that Cillian Murphy is right: it’s perfectly possible for filmmakers to achieve spectacular box office results by provoking and challenging audiences.

Still, it’s always a risk. While bookies have already got Oppenheimer as the favourite to win the 2024 Oscars Best Picture award, its triumph won’t likely lead to a new wave of brainy blockbusters. Doctor Zhivago, The Graduate and The Exorcist all had maverick directors studios were ready to roll the dice on and they’ll do the same for Nolan, sure, but there aren’t many others around who’ll be given the same license. History suggests that originality can work at the box office but, when it comes to blockbusters, Hollywood remains a conservative town. The instinct is to stick with known properties in the form of franchises and sequels. That would explain the line-up for the next few months: Ghostbusters, Aquaman, Kung Fu Panda, Dune, and Godzilla, alongside the usual Marvel sequels and spin-offs. Beyond Martin Scorsese’s Killers of the Flower Moon and Ridley Scott’s Napoleon (both underwritten by Apple Original Films), audiences who are hoping for big movies that don’t look and sound exactly like their predecessors will be looking in vain. One film about a porkpie hat-wearing physicist won’t change anything. Just because Oppenheimer is a hit, don’t think that means more test tube movies down the line. Chances are, it’ll be superheroes over scientists for a long while to come, with only Timothée Chalamet’s Willy Wonka giving us any respite from the ongoing, testosterone-driven monotony.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments