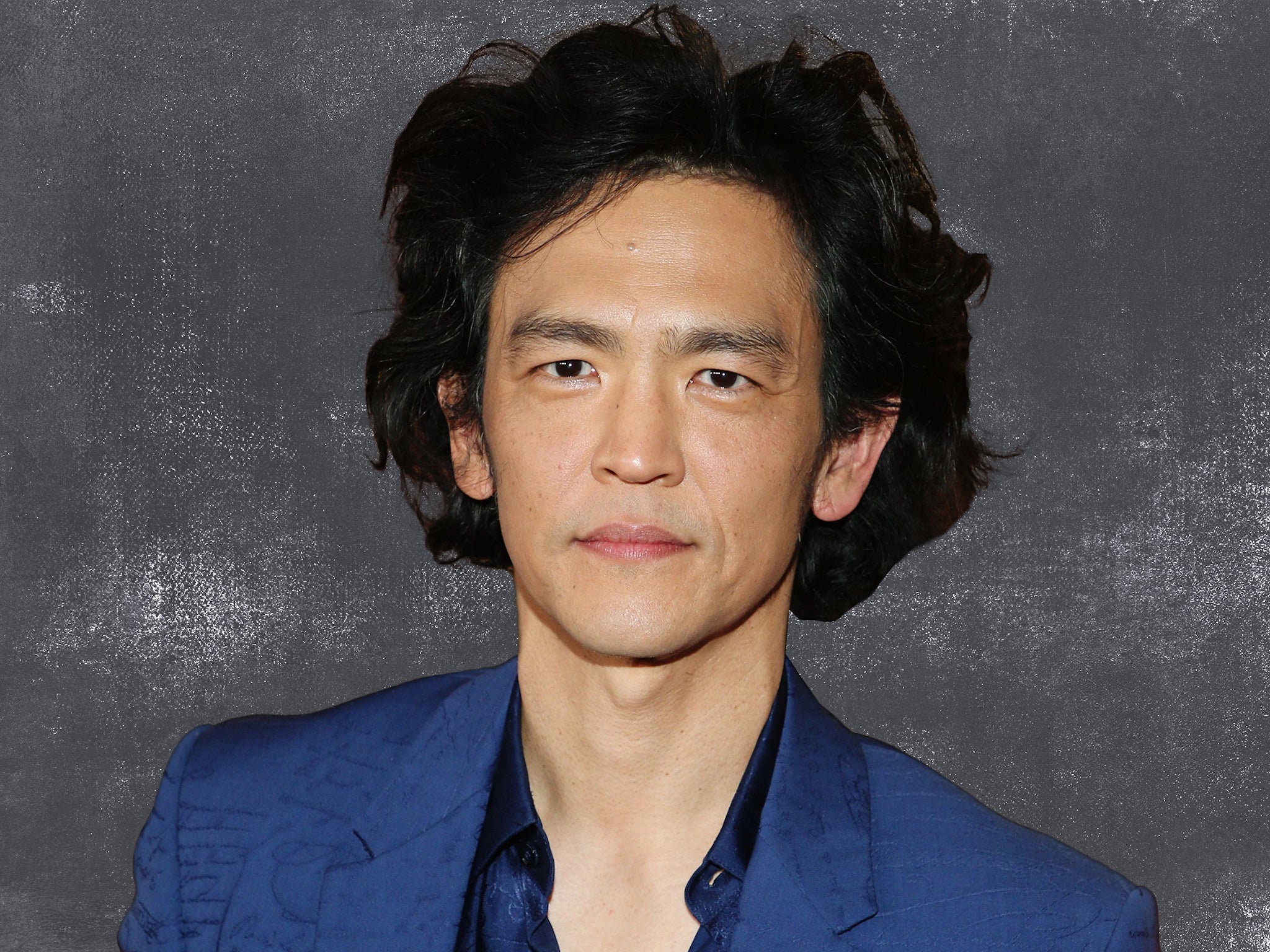

John Cho: ‘A movie that treats race in the background feels more authentic... people don’t think about their race throughout the day’

From ‘American Pie’ to ‘Cowboy Bebop’ and Amazon’s new film ‘Don’t Make Me Go’, Cho is an actor on the rise. He talks to Annabel Nugent about growing up with a sense of shame, protecting his privacy, and his desire to do a film about a killing spree

For what it’s worth, John Cho is sorry. “Listen, I’ve sent my letters of apology to all the nations of the world.” In fairness to him, he wasn’t the one to coin the term “milf” – only the one to popularise it, thanks to a small but notorious part in 1999’s American Pie. More than two decades later, the raunchy comedy’s legacy – including that catchy epithet for sexy mums – is lasting.

“I’m sorry I unleashed that,” Cho jokes as he appears on Zoom. At 50, the actor looks scarcely older than he did playing a high-schooler taking shots off a girl’s chest. “I always thought ‘milf’ was a vulgar term, but I will say there are a lot of women who self-identify as that, so somewhere it took a turn.”

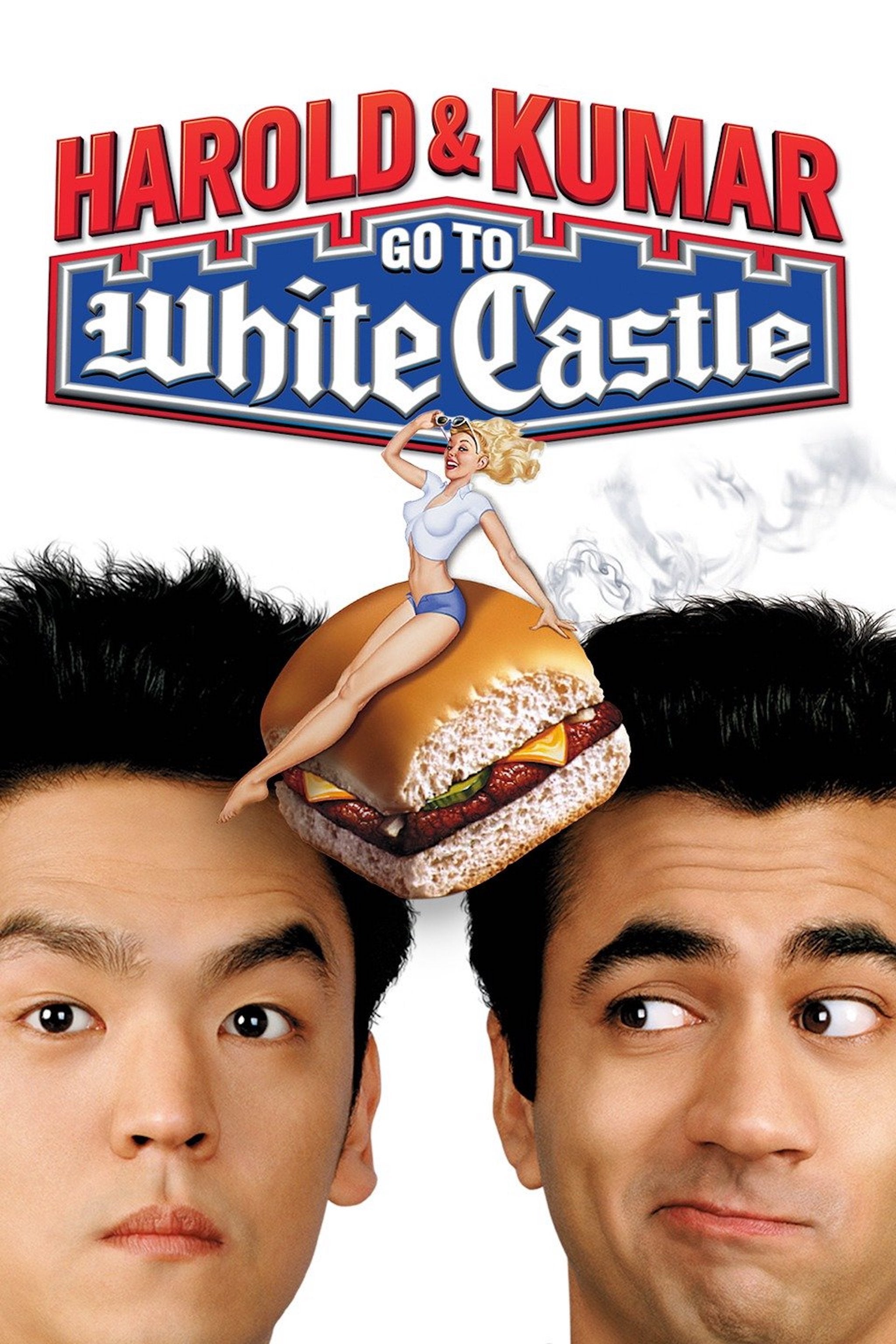

The same can be said of Cho’s career: somewhere it took a turn. After “MILF Guy #2” in American Pie and “Sale House Man #1” in American Beauty came a string of TV appearances in high-profile shows such as New Girl, How I Met Your Mother, and Grey’s Anatomy. There were movies, too. Harold and Kumar Go to White Castle revolutionised the stoner genre. Cho played Harold to Kal Penn’s Kumar. Truly, a triumph for PoC potheads everywhere.

Then came the chance for Cho to emulate his childhood hero, his “North star”, George Takei, as Sulu in JJ Abrams’s Star Trek trilogy. Slowly but surely, he became one of the most recognisable faces in Hollywood – not least because there were so few others who looked like him.

For a long time, Cho’s roles could be reduced to “the Asian guy in that thing”. The descriptor typically spawned three names: Steven Yeun from The Walking Dead, Daniel Dae Kim from Lost, and Cho from, well, everything else. It wasn’t until Columbus, a modest and cerebral 2017 drama, that Cho was finally given material he could really tuck into. The critically acclaimed film earned him some of the best reviews of his decades-spanning career.

It signalled another turn, this time into leading-man territory. Since then, he has won over critics again with 2018’s intimate thriller Searching, and played the lead in Netflix’s live-action adaptation of Cowboy Bebop, a beloved space-Western anime. Now, he slips comfortably into the role of a single dad in Amazon’s Don’t Make Me Go.

Anyone paying attention will know it’s high time that Cho ascended to top billing. The actor himself is less fussed. “Every part of my career has felt very gradual. I was never discovered on a street corner, leaning against a mailbox wearing a jeans jacket.” He pauses for a moment and then lets out a deep cackle. “That was oddly specific.” The mailbox detail, he explains, is how Matt Dillon was found. “Meanwhile, I’ve just been plugging away,” he shrugs, speaking of his newfound fame. That said, it is seldom just perseverance that makes a star. Good hair helps, too.

Despite having half a century under his belt, Cho has more hair than ever. In addition to a well-groomed handlebar moustache, he is sporting a bedhead bouffant: the sort of style that evokes endless metaphors about clouds and cotton candy. I’ll spare you. What I will say is that it’s easy to see why, when Cowboy Bebop debuted last year, “JOHN CHO’S HAIR” trended on Twitter. And no, it’s not a wig.

Cho’s latest film is a tearjerker. In it, he plays Max, a single dad who takes his teenage daughter on a cross-country road trip after discovering he has only months to live. It follows on from Searching, another father-daughter story. Cho has two kids of his own: the first, a son, was born in 2008. In that moment, everything changed for him.

“It’d be easier to say how being a dad hasn’t changed me. Having a kid is a total alteration of your life and your values. It feels like everything gets rearranged and put in its proper place inside you,” he says, gesturing in circles at his abdomen. Raising two children has led him to re-examine his own childhood, which was spent in South Korea and in the US, where he moved to aged six.

“I want to emulate most things my parents taught me, like love, kindness and morality – but there are a couple of cultural things that I want to consciously put a stop to.” Like shame, he says. “I grew up with a sense of shame. It’s a cultural thing meant to teach us how to behave and be civil with one another, but the methodology was shame, and I don’t want that to be the driving force for my kids in how they conduct themselves in the world.” Another thing, he adds, is that Korean culture is “pretty patriarchal”.

As an actor, Cho exists in a unique space. He is the rare Asian star whose roles, recently at least, have little to do with his Asianness. Don’t Make Me Go is no different. The film treats race as extraordinarily unextraordinary. That Max is Korean is by-the-by. It’s the latest in a carriage of characters that treat Cho’s heritage as incidental rather than fundamental. For his part, Cho can recognise a pattern in his choices, but says he has no “philosophy” when it comes to choosing roles. “It’s situational,” he explains.

“But a movie that treats race in the background feels more authentic, because while the rest of mainstream society in America looks at you and sees solely the colour of your skin, internally people don’t think about their race throughout the course of a day. Other identities are much more forefront in your conception of yourself.” I nod in agreement, joking that I don’t wake up every day and think of being Asian first thing. Cho quips, “You don’t?” He feigns shock, mouth agape. “Every morning I look at myself in the mirror and think, ‘Ah, there I am: still Asian!’”

No one is more surprised by the rise of John Cho than John Cho. While his race didn’t define him, it no doubt cast a shadow over his ambitions. Growing up in early Eighties LA, the idea that someone like him could have the career he has now was laughable. Today, he’s reluctant to call it pessimism. “I would argue that my opinion was really evidence-based,” he states. “I didn’t see anyone who made that feel possible.”

The few shows, like M.A.S.H, that did feature Asian actors did so seemingly without thought. Their roles were so insignificant and truncated that, as a child, Cho didn’t believe they were professionals. “I thought the show had just got these dry-cleaners to be in it. It didn’t seem to me as a kid that what they were doing was the same as what Sylvester Stallone was doing, you know? Those are different jobs.” And oftentimes, he adds, “actually they were just there so we could make fun of them”.

As is true for many people, Cho’s worldview shifted in college. He studied English literature at Berkeley in California, where he also first tried acting. “I met these Asian American actors, and I was like, ‘Holy s***, these are actual actors. They’re trained and they’re educated and they’re earning a living.’”

Onscreen, however, the representation he saw was still dire. So, Cho turned his eye instead to films from Hong Kong and Korea. “In these movies, we’re beautiful people going through the whole gamut of the human experience,” he says. It raised questions for him about American entertainment: “How come, then, we’re such weirdos and dickheads in that?”

Cho always had a clear idea of the roles he wanted to play. And one early experience gave him an idea of the ones he wanted to avoid. In 1997, Cho made a cameo on The Jeff Foxworthy Show, playing a delivery driver. He has previously said he regrets taking the part. “I was playing a Chinese delivery guy with a Southern accent. That was the joke,” said Cho – who is Korean, thank you very much. “I remember doing it and the white crew laughed. I was so uncomfortable. I didn’t ever want to have that feeling again.” Cho made sure he never would.

When a potentially star-making opportunity opened up in the 2002 comedy Big Fat Liar, he turned it down because the character called for an accent. It wasn’t because the part was written with malice, Cho clarifies. “I just felt that since it was a kids’ movie, children could mistakenly laugh at the accent, thinking that was the funny part.”

Speaking up was tough, but writer and director Shawn Levy made it easy. He listened to Cho and wrote out the accent. Easy peasy. Levy’s response set a benchmark for how Cho would approach similar qualms in his career. “It’s always valid to speak your heart. You just have to be able to live with the consequences. If you can’t, then you can’t speak your mind.”

I’ll tell you a secret: my generation of Asian American dudes, we all walked around with a fist in our pocket

The decision isn’t always as clear as you’d think. Cho recalls a period in his life when he was receiving a lot of scripts for what he calls “Is this racist?” roles. “They weren’t outright racist, which made it difficult to assess,” he laughs. “The tricky thing is when it’s stuff that’s anti-stereotype, but it relies on the stereotype for the joke.” He uses an Asian ladies’ man at a strip club as an example. “Is that a perversion of the stereotype, where we’re supposed to laugh at how absurd it is? If so, it’s still the stereotype but dressed in sheep’s clothing.”

To help him decipher what was and wasn’t offensive, Cho had a “little network of dudes” he’d call up for advice. “It was like a red phone hotline.”

In 2016, a social media movement by digital strategist William Yu reimagined Cho as the protagonist of action franchises and romcoms. #StarringJohnCho saw the actor’s face photoshopped onto posters for The Avengers and Spectre to advocate more Asian Americans being cast in traditional leading roles.

“It was very weird to see myself in those things,” he recalls, adding that playing James Bond or Captain America had never been his goal. “Maybe it’s because I edited my own dreams?” he muses out loud, but swiftly moves on. “The awkwardness of that campaign was that a lot of people thought I was the one to start it!”

As perfectly pleasant as Cho is – and he is, by the way, smiley and earnest – you get the sense that he doesn’t want to be here, talking about this. Earlier in his career, perhaps, but over time he’s mellowed out. These days, he’d rather be at home with his kids. “It’s a tough time doing media now. I think the requirement to reveal your inner depths is higher than ever,” he says, pointing to the current landscape in stand-up comedy as an example. “It’s all very revealing, very personal. That’s what people want, but that’s the part of myself that I’m most protective over.” Listen, he says to me, “I’m doing a movie about a father and daughter, and so people want to know about my daughter, and I’m very defensive about that because it’s my business.”

An inevitable consequence of coming up in the Noughties as an Asian actor is that you become a beacon of representation. And the sheer longevity Cho has achieved in a fickle industry (“I’m like a virus that can’t be stamped out”) has made him an ideal, if at times reluctant, spokesperson on such issues. Cho has a tough time giving a verdict on whether cinematic victories can lead to meaningful change. He approaches the question as a dad, as opposed to an actor.

“You know, being an Asian kid, there were so many opportunities when you were made to feel different, and that seems to have changed. I think pop culture has a lot to do with how children see other children who look different from them. And now I think kids are much cooler with a multicultural world.” His daughter, he smiles, loves Moana. “And I love that she loves Moana, and I love that she has Moana. Representation is important in a way I couldn’t have conceptualised.”

What’s next for Cho is up in the air, but he has some ideas. One is an uber-violent action flick where he just kicks the s*** out of people for two hours. It’d be his “love letter” to fellow Asian American men, he smiles. It’s a definition that begs for an explanation.

“Maybe it’s different for the younger kids, but I’ll tell you a secret: my generation of Asian American dudes, we all walked around with a fist in our pocket,” he says. “I know a good number of my friends, you push them a little too far and the rage comes out, and it’s very difficult to put that back in the bottle, so I wanted to do a film where it was just a killing spree! Me laying waste to everyone.” He laughs manically. “I just know there’s a segment of Asian American men who would be like, ‘Thank you!’”

‘Don’t Make Me Go’ is available to watch on Prime Video

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks