Rose Byrne: ‘Heath Ledger was so instrumental in helping me get work’

The Australian star of ‘Bridesmaids’, ‘Damages’ and the dark Apple TV+ comedy ‘Physical’ talks to Adam White about refusing to play a ‘nagging wife’, her friendship with Heath Ledger, and why we should remember aerobics as a revolutionary step in Eighties feminism

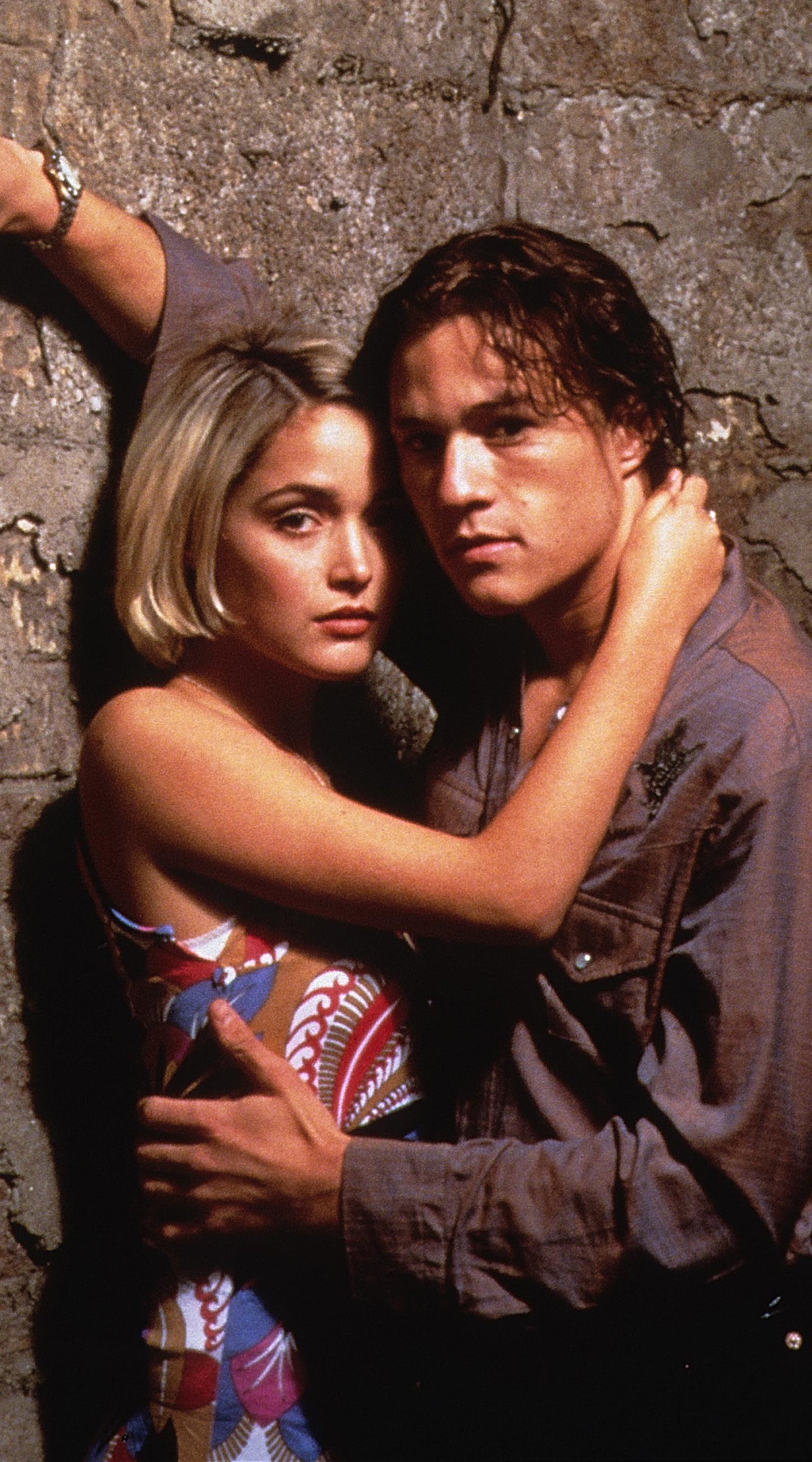

The road was long and unwieldy, but Rose Byrne and Heath Ledger were both barrelling down it head first. It was 1999. Together the 20-year-olds were Australian imports freshly arrived in Las Vegas, taking photos to promote a tiny indie movie they’d made back home called Two Hands. “We’d been to a vintage clothing store on Melrose Avenue in LA and got all of these crazy costumes,” Byrne remembers, wistfully. The resulting shoot seems to get reshared on Twitter every six months or so. There are big sunglasses. Plastic flowers. Sixties flares. “It was so silly, and you can see in the photos a lot of joy. We’re in a limousine drinking champagne… we were just kids. There were so many possibilities. It felt like anything could happen, like we were in this huge, almost Wild West of America. You cling to each other even more when you’re from [a place] really far away. Like we were.”

It’s a bit jarring to remember that Byrne and Ledger were once on identical trajectories, newcomers at the turn of the millennium with no idea of what was in store for them. Today, Byrne is 42 and has lived full-time in the US for nearly two decades, starring in films as diverse as Bridesmaids, Sunshine and Spy, and TV series such as the legal thriller Damages and the dark comedy Physical. Her métier is the buttoned-up neurotic; a woman who masks chaos behind plastic smiles. But that doesn’t quite nail her, either. “I don’t think people really associate me with anything,” she laughs. “Except for maybe a general familiarity.”

Twenty-three years after that trip to Vegas, Byrne is in a different vehicle, albeit one taking her to work. When she calls London, she’s en route to the set of Platonic, a forthcoming limited series in which she stars alongside Seth Rogen, her on-screen husband in the frat-house comedy Bad Neighbours and its sequel. She hasn’t got her camera on, citing her car sickness. To combat it, she says, she’s just looking straight ahead, laser focused. It feeds into the impression that Byrne is a bit of a worrier. She answers questions fastidiously, her answers a mix of rehearsed responses and off-the-cuff candour. She chastises herself for being inarticulate at one point; twice she says she’s boring.

They’re casual self-criticisms that remind me of the character Byrne plays in Physical. Sheila Rubin is an ambitious aerobics instructor trying to thrust and star-jump her way through Eighties California. Standing in her way, though, is an unhappy marriage and an eating disorder. As a premise, it’s pretty niche, but it also taps into something universal. In often oppressive voiceover – a turn-off to many during its first season, it’s been blessedly curtailed for its second season – Sheila chides her personality, the stupid things she says out loud, and the important things she doesn’t. To varying degrees, it’s something a lot of us do as well. Often, we don’t even notice it. One person’s destructive self-loathing is another person’s embarrassment in an interview when an answer comes out garbled.

In its second season, which is dropping weekly on Apple TV+, Physical becomes a lot frothier than it used to be, but also graver, stranger and more psychologically complex. Byrne has to steer a character who becomes increasingly more of a lady-boss in the fitness industry – her outfits, it should be said, are Jane Fonda by way of Joan Collins in Dynasty – while collapsing internally due to mental illness.

“The show is polarising, but I’m proud of that,” Byrne says. “Good art can be challenging and difficult and still be fun.” She suggests Sheila was more enjoyable to play this time around. “[This season] you see in her what other people see, rather than just the torture of her illness. It’s becoming more and more about her empowerment, but also about her recovery, or the ‘performance’ of recovery.”

The rise of aerobics was revolutionary for women, but it’s not something that’s taken very seriously

The show, she adds, is also a historical document, and an accidental companion piece to her previous TV role: playing the prominent US feminist Gloria Steinem in the Seventies-set mini-series Mrs America. Physical picks up on some of the same themes – feminism, power, women in the workplace – a few years later, and practically chronologically.

“That moment was such a turning point,” she says. “If you look at the wellness industry today, where everyone has an athleisure line, or a wellness app, [the Eighties] is where the seeds of all that began. The rise of aerobics was revolutionary for women, but it’s not something that’s taken very seriously. It changed a lot of people’s lives, and was a place where women found a lot of agency through economic independence.”

She’s a realist, though, when it comes to what the industry ended up becoming. “It exists in two ways,” she says. “I think it can be genuinely fulfilling and also kind of self-serving for narcissists. It’s a very, very grey space. There’s a lot of benefits to it, but there are also a lot of charlatans.” She scoffs. “It’s, you know, overrun with charlatans. But that’s what makes it an interesting thing to examine.”

Somewhat impressively, Byrne has gone through two seasons’ worth of press interviews for Physical without talking very much about her own relationship with her appearance, or body image in general. She says she didn’t even use her own history as a reference point to play Sheila. Method she most certainly is not. “I’m not particularly interested in dredging up my own personal experiences,” she says. “If the script is good, then it’s all there.” Plus, she had the show’s creator Annie Weisman to turn to, with Sheila’s illness inspired by Weisman’s history with eating disorders. “She’s always been my touchstone for all the emotional beats and all my questions,” Byrne says. “Without that touchstone, it would have been a bigger decision for me to even take the part.”

Last year, Byrne told The New Yorker that she and her actor husband, the ubiquitous – if not quite a household name – Bobby Cannavale, move through the world very differently. Tall, broad and loud, he’s approached by people constantly. She, though, can disappear. Professionally, it’s been an asset and a liability. “It means I can vanish into parts,” she says. “But this is a business, too. People want that instant hit, that instant gratification. I definitely don’t fall into that category. I probably fall into the category of character actress, which is not [me] trying to humble-brag or anything, it’s just a hard business to place yourself in. I definitely was not a confident 20-year-old or even a confident 28-year-old, you know? It’s taken me a long time to feel more in my skin. It’s dull of me to say, but I do always feel grateful to have consistently been a working actress. It’s not easy. It’s a tough business, and people tend to fall in traps or rely on other things to get [them] through it.”

Byrne has been acting professionally since she was 15. She did a lot of theatre in her native Sydney, followed by a handful of low-budget indies. Oddly for an Australian, she managed to completely bypass the Home and Away-to-Hollywood pipeline. Instead, she ventured to America, spurred on by Ledger. “It was a whole mix of us: actors who got work, actors who didn’t,” she remembers. “Being Australian, you’re outsiders, aliens, so you’ve got to band together. Heath was a real champion of that. He left early and started to get work here. He was so instrumental in helping me and a lot of people get work, and get into rooms.” Did it feel like an adventure? “It did! Just all of us driving to Joshua Tree, or staying at Heath’s [house] in Los Feliz. We were all in our late teens or early twenties, and there was such fervour to it all.”

Work came steadily. There were small parts in Star Wars: Episode II (she played one of Natalie Portman’s handmaidens) and Sofia Coppola’s Marie Antoinette, followed by Damages and a much-desired break into comedy via Bridesmaids and the tragically underseen British romcoms I Give It a Year and Juliet, Naked. She alludes to a few early years of frustration, though. “I’ve done my fair share of parts that didn’t have agency, that weren’t that interesting,” she says. By the time she was offered Bad Neighbours in 2014, she knew the kinds of roles she didn’t want to play any more. It’s even referenced in the film itself. “I’m the dumb guy and you’re the woman who’s supposed to stop the dumb guy from doing dumb s***,” Seth Rogen’s character says at one point. “Haven’t you ever seen a f****** Kevin James movie? We can’t both be Kevin James.” Byrne’s character protests such a claim. “It’s offensive that I have to be the smart one all the time,” she argues. “I’m allowed to be just as irresponsible as you!”

“Our early conversations once I got the part were about how I’m just not interested in playing a nagging wife,” Byrne recalls. “That’s about as interesting as a piece of toast. So it was always about making the two of them just as destructive and irresponsible as one another.” Bad Neighbours also marked one of the rare American films Byrne’s made in which she’s been allowed to keep her natural accent. It hasn’t been diluted in her time away from home, but it becomes noticeably stronger as our conversation goes on. Down the phone line, it veers from ambiguously mid-Atlantic to Kath & Kim in the space of minutes. She says that not being American has been an asset to a lot of her work.

“It keeps you at arm’s length a little bit, or allows you to see the smaller intricacies that you couldn’t see if you grew up totally immersed in America.” She pauses. “Because I still feel so Australian! To this day, I wake up and go: ‘Hold on, where am I? How did I get here?’”

‘Physical’ season two is streaming weekly on Apple TV+, with new episodes dropping on Fridays

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks