Hugh Grant has never been the terrible actor he insists he is

No one is more disdainful of Hugh Grant’s three decades of superstardom than Hugh Grant himself. But as the self-deprecating actor steals the show as an Oompa-Loompa in ‘Wonka’ – despite insisting to the press that he hated every miserable second of making the film – Geoffrey Macnab explores his strange, scandal-surviving and actually quite brilliant career so far

Maybe Hugh Grant was always destined to play an Oompa-Loompa. It isn’t a fate he appears to be relishing, though. This week the actor is seen as the diminutive Lofty opposite Timothée Chalamet’s Willy Wonka in Wonka, a prequel to Roald Dahl’s Charlie and the Chocolate Factory. Early reviews have been very generous (“comes close to pinching the whole thing,” “uproarious” and “delightfully silly”), but there’s no getting around the fact that this is not an elegant look for Grant: the usually svelte star of Richard Curtis classics Four Weddings and a Funeral (1994), Notting Hill (1999) and Love Actually (2003) here resembles nothing so much as a grizzled garden gnome. He has orange skin, green hair, and his oversized head is attached to a tubby, tiny little body.

“I couldn’t have hated the whole thing more,” Grant recently said. This was a role heavily dependent on animation and special effects, and he found it all excruciating. He’s also told the press that he “slightly hated” the process of making films in general, but that he had “a lot of children and needed the money”.

This was (partly) the kind of deadpan irony in which Grant has always excelled. Few other actors could get away with remarks like these on the eve of a major movie release, but Grant has a very British knack for understatement and self-deprecation. If he really disliked the experience of making Wonka, he presumably wouldn’t be travelling the world to promote it. He must have been gratified, at least, to hear himself described by Chalamet as “one of our greats”, although it may have dented his vanity to have been cast as young Wonka’s stooge. Only a few years ago, he would surely have been the main man.

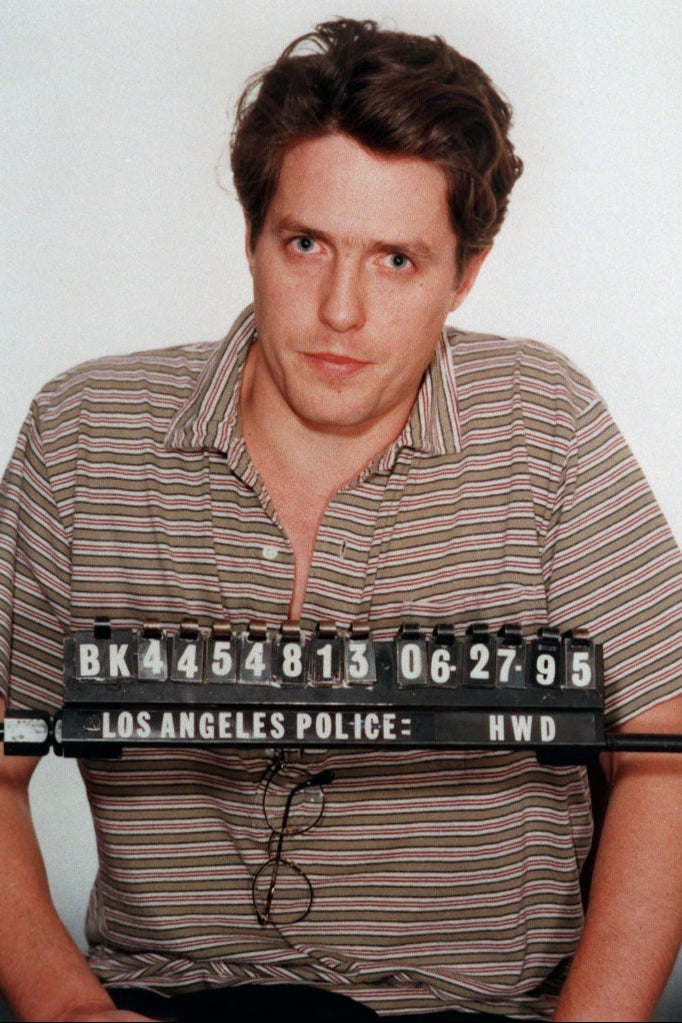

Grant isn’t just one of the UK’s biggest movie stars of the last 30 years, he is also its most obdurate survivor. He has overcome scandal (such as when he was caught in a car with a sex worker at the height of his early fame), negative press (the media turned against him partly because of his association with the Hacked Off campaign against press intrusion), and more than his share of flops.

True to form, Grant’s casting as the Oompa-Loompa has caused yet another rumpus. Why, some critics asked in the build-up to the release, is Grant playing the role instead of an actor with dwarfism? But, as usual, Grant hasn’t been touched by the controversy. It would be stretching it to say that the star’s roots are in old fashioned vaudeville. He is a public school boy and Oxbridge graduate from a military family. However, he has always been more of an old fashioned entertainer than some of his fans realise. Long before he was sweet-talking Julia Roberts in Notting Hill or making mooncalf eyes at Martine McCutcheon over tea and biscuits in Love Actually, he used to make a living from “doing silly characters,” as he’s put it.

During his varsity days, Grant played Hamlet in a production that travelled to the Edinburgh Festival – but he wore a Star Trek outfit for the role. A devotee of Monty Python, he did a stint as an advertising copywriter, working on ads for everything from lager to bread brands. He also co-founded his own comedy troupe, The Jockeys of Norfolk, which performed at the Fringe and did well enough to land its own TV show. One of their skits involved recreating the Nativity as if it was an Ealing comedy.

Grant was first seen on the big screen as an “aristocratic drop-out” in Privileged (1982), an Oxford University production that saw him credited as “Hughie”. Directed by Michael Hoffman, it revolved around the romantic conspiracy and backbiting going on behind the scenes of a production of The Duchess of Malfi.

In the film, Grant cuts a strangely overwrought figure. He plays Lord Adrian, a neurotic and jealous young toff (the type of character you’d expect to see today in a film like Saltburn) who is so angry that his beloved Lucy is cheating on him that he challenges her lover to a duel. With his floppy hair and epicene good looks, he looks disconcertingly like a young Chalamet – but he’s in a supporting role, someone needy and unsympathetic.

Grant later claimed he had made Privileged “just as a sort of joke” and that he subsequently became a professional actor by accident. “It got this premiere,” he said. “Agents came up and said, ‘Do you want to act?’ I thought it would be amusing to do that for a year while I worked out what I really wanted to do.”

Those who knew him in this period remember it differently. Andy Paterson, who has gone on to make many other high-profile movies including Girl with a Pearl Earring (2003) starring a young Scarlett Johansson, was a producer and assistant director on Privileged. “Hugh was an established figure in the theatre community [at Oxford University],” he tells me, dismissing any idea that he was a rank amateur or dilettante. “We just cast the best people.” Paterson acknowledges that Grant’s role wasn’t especially well-written. “But what he did do was bring that glimpse of the movie star.” It was obvious to everyone, he adds, that Grant “worked on camera. He was photogenic in a way that was apparent immediately.”

A few years later, James Ivory chose Grant to co-star in his EM Forster adaptation, Maurice (1987), an Edwardian-era drama about two young male Cambridge students who fall in love. “It was almost the first unapologetic homosexual film,” Ivory later said, “[and] wasn’t done in a half-apologetic, clandestine way. I think that was its appeal.” Maurice was released in the middle of the Aids crisis and treated with great respect by critics. It also ended up winning Grant and his co-star James Wilby a shared Best Actor award at the Venice Film Festival.

Grant, however, failed to capitalise on the film’s success. “I squandered the opportunity afterwards by doing a lot of rubbish,” was how he put it – in typically terse fashion. Another seven years were to pass until Four Weddings finally catapulted him to international stardom. “I was so bad in my early films I thought if I just do one more, I’ll prove that I wasn’t quite that bad,” he told podcaster Marc Maron in 2021. This fallow period saw him appear in a number of half-baked European arthouse movies, as well as a few schmaltzy miniseries. There was one Judith Krantz adaptation (1989’s Till We Meet Again), and even a Barbara Cartland miniseries (The Lady and the Highwayman, also from 1989).

“I was always a champagne baron, an evil one who stole the family champagne and sold it to the Nazis and raped Courtney Cox, my half-sister, and got whipped out of the house by Michael York,” he’d later say. “I always had a little moustache.” Among his more high-profile projects during this period were Roman Polanski’s erotic thriller Bitter Moon (1992), playing Kristin Scott Thomas’s comically repressed husband Nigel, and Ken Russell’s extravagant gothic horror film, The Lair of the White Worm (1988), in which Grant was cast as Lord James D’Ampton, descendant of a warrior who had slain a mythical serpent.

Four Weddings changed everything. Andy Paterson was working with Grant on the 1995 period movie Restoration, also directed by Privileged’s Michael Hoffman, just as the romcom arrived in cinemas. “We were shooting in Dorset… suddenly there were paparazzi in the bushes, just trying to get a glimpse of Hugh. It was hilarious.”

Then came Grant’s awfully big American misadventure. When his first Hollywood movie, Nine Months (1995), was about to be released, he was arrested for “lewd conduct” with sex worker Divine Brown. “My timing was impeccable,” he later joked. A lesser actor would have sunk without a trace. However, the movie was still successful commercially. Grant fronted up on talk shows and was soon forgiven.

It wasn’t, though, as if the media was going soft on him. By now, the British actor was under mass surveillance from the tabloids. His phone was being tapped by the red tops, who had been obsessed with him ever since he began dating Elizabeth Hurley – the attention reached fever pitch when Hurley turned up to the Four Weddings premiere in a revealing Versace dress held up by safety pins. It was also becoming painfully clear to Grant that audiences didn’t like him to stray too far from the archetype of the lovable, repressed Brit.

“I did a film with Sarah Jessica Parker,” he said in 2009, of the 1996 thriller Extreme Measures. “People said, ‘You should do something different’ … Actually, it’s not a terrible film. But 11 people around the world went to see it. It’s not that I love romantic comedies. In many ways, I hate them. But it’s something I feel, ‘I can do this’.”

There came a time, though, when even the romcoms no longer worked. In an interview with the LA Times, he spoke very frankly about how the terrible box office performance of his screwball comedy Did You Hear About the Morgans (2009) scuppered his Hollywood career. “The days of being a very well-paid leading man were suddenly gone overnight,” he lamented.

But since then, ironically, he has landed some of his best roles. He was superb as the creepy but still very personable Liberal party leader Jeremy Thorpe in Stephen Frears’ miniseries A Very English Scandal (2018), in which he preyed upon and eventually tried to murder his naive younger lover (Ben Whishaw). He was equally good as the surprise villain in the 2020 thriller series, The Undoing. At last, he was being allowed to get in touch with his dark side.

Grant was also ready to ham it up when required. He evoked memories of Terry-Thomas and was in full blown pantomime-baddie mode as Phoenix Buchanan, an embittered thespian reduced to doing gourmet dog food commercials, in Paul King’s Paddington 2 (2017). He’s also turned up as dodgy arms dealers and private detectives in Guy Ritchie movies such as The Gentlemen (2019). He gave a very good performance, too, playing the companion and sycophant-in-chief to shrill-voiced opera singer Meryl Streep in Frears’ comedy-drama, Florence Foster Jenkins (2016).

Now, Grant is the “funny little man” stealing scenes in Wonka. He is, though, yet again pushing the line that he’s an accidental movie star who would rather be doing anything else other than making films. Audiences, of course, know better.

“There are just characters that you adore on screen automatically,” Paterson says. “Although we were all very much starting out [on Privileged], making it up as we went along, you could tell there was that presence. He is a much better actor than he has ever really allowed himself to believe.”

‘Wonka’ is in cinemas

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks