‘What the hell were you thinking?’: How Hugh Grant’s arrest for ‘lewd conduct’ changed the way celebrities say sorry

The ‘Four Weddings’ star was seen as the quintessential posh Englishman until a 1995 sex scandal threatened to end his new Hollywood career. Adam White looks back at what happened next

It was the early hours of a Tuesday morning, 27 June 1995, and a sex worker known as Divine was about to become an international sensation. And all because the randy, stammering and vaguely annoying Englishman who solicited her services on the corner of Sunset Boulevard was a fledgling movie star named Hugh Grant.

The resulting scandal remains one of the most iconic celebrity stories of the 1990s. “Hugh and the hooker”, as it was spoken of in tabloid patter, was a collision of worlds deemed at odds – rich and poor, a white man and a black woman, a stuffy and reserved Brit and an American steeped in the sex industry. Its surface contradictions remain juicy, but, 25 years on, it’s what happened after that is most compelling.

Grant’s decision to own up to his actions, get ahead of the story and embrace the egg on his face was one of the greatest celebrity mea culpas in modern history. The lessons it imparted, and the career it didn’t destroy as a result, are just as relevant today as they were then. In an age of so many celebrity apologies and high-profile snafus, it’s arguably never been more important.

The incident in question came after a night of drinking and dining, with Grant and his co-stars Jeff Goldblum and Tom Arnold having completed two days of press interviews for their new film, Nine Months. A pregnancy comedy, it marked Grant’s first American star vehicle, one designed to build on the unexpected US success of 1994’s Four Weddings and a Funeral. Nine Months borrowed many of its flibbertigibbet, toff tropes, if not any of the funny lines or heart. It was scheduled to open in two weeks.

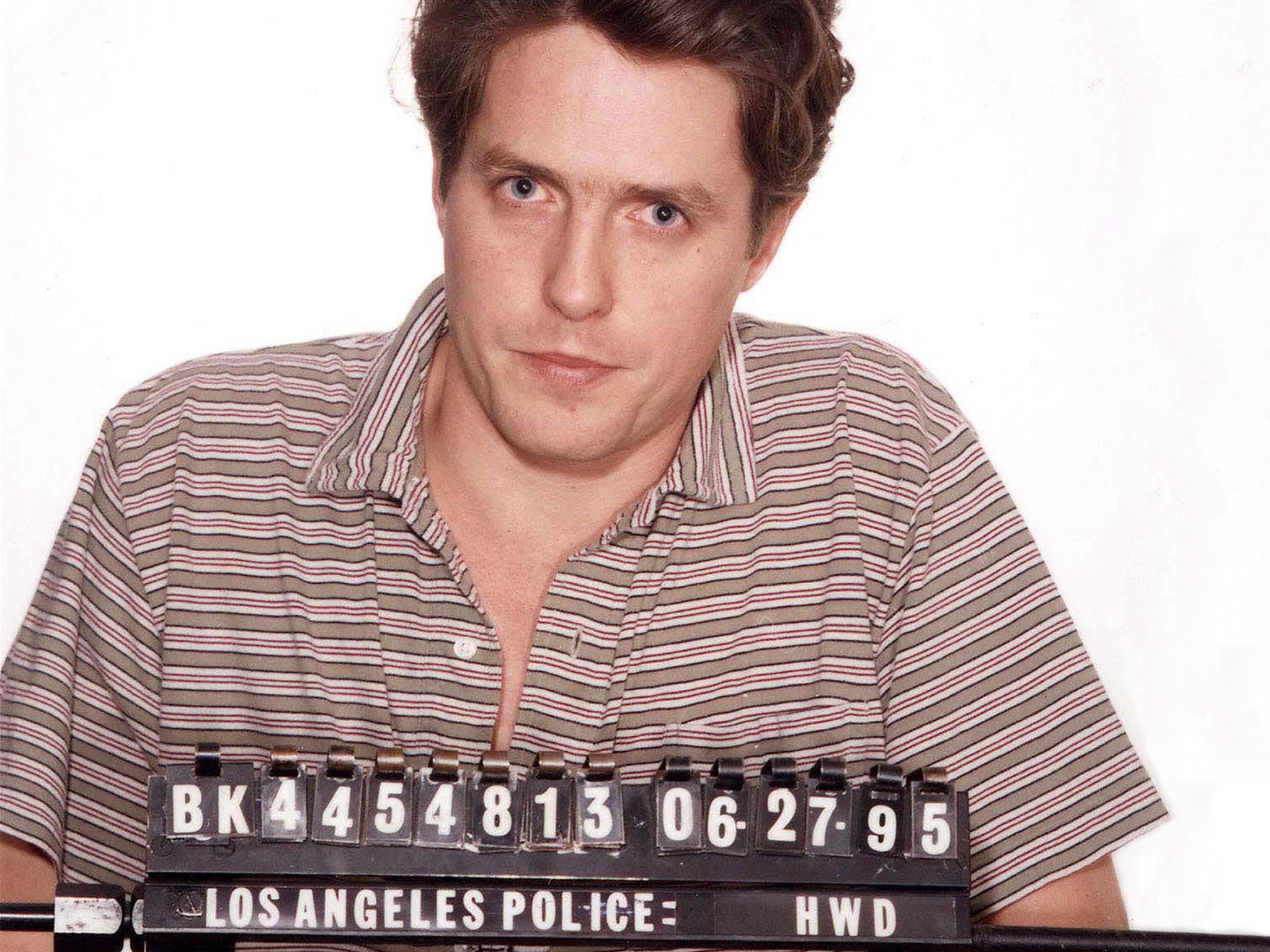

At 1.30am, Grant’s white BMW hit the notorious Sunset Strip, in West Hollywood, where he picked up Divine Brown, born Estella Marie Thompson, a 23-year-old sex worker. Parking the car on a nearby residential street, Grant and Brown were almost immediately set upon by police, who arrested the pair for engaging in “an act of lewd conduct”. Within hours, the world’s tabloids were on fire – “Hugh Dirty Dog!” yelped the New York Post, Grant’s immediately infamous and sheepish mugshot splashed across its front page.

After he was released on $250 bail, Grant’s publicity team sprung into action. “Last night I did something completely insane,” Grant said in a statement. “I have hurt people I love and embarrassed people I work with. For both things I am more sorry than I can ever possibly say.” Observers questioned whether Grant had swiftly killed his career, spoiling the debonair image he had cultivated via Four Weddings, and jeopardised his relationship with Elizabeth Hurley. The pair had already become two of the most photographed stars of the era, both benefiting from their shared upper-crust glam. “Sean Penn could get away with this,” one anonymous female film producer told People Magazine. “But not Hugh Grant. Every woman in America wanted him to take her out for a malt. Now the buzz in the secretarial pool is, ‘Oh, yuck’.”

What happened next was partly guided by contractual obligation. Nine Months was too close to release to postpone, talk show appearances had been booked, and too much money was on the line for Grant to disappear altogether. While his personal life was on life support, with he and Hurley photographed looking stricken on the grounds of their country pad within days of Grant’s arrest, the show had to go on. Enter Jay Leno. His US talk show played host to Grant 11 days after his encounter with Brown, Leno opening the interview with an immortal question that would go down in chat show history: “What the hell were you thinking?”

Grant’s appearance on the show is a masterclass in self-deprecation – there’s the faltering nervousness of his onscreen characters, the genuine remorse, if a slight glimmer of exaggeration when it comes to his facial discomfort. “It’s not easy explaining,” Grant told Leno. “People have given me tons of ideas on this one, from ‘I was under a lot of pressure, I was lonely, I fell down the stairs when I was a kid’, but I think it would just be bollocks to say anything like that … I’m sure I would be enjoying this as much as everyone else [if I were watching], but it’s horrible when you’re on the other end.”

Leno was a famously soft touch as a talk show host, and even Grant had remarked on the ease of using English charm to sell yourself in the USA: “You’ve only got to say ‘Bloody hell!’ to have them thinking how delightful you are,” he told an Empire magazine journalist at the Nine Months junket, ironically on the same day he’d be arrested and needed to rely on said charm to salvage his career. But the openness with which Grant approached the incident was groundbreaking. The criminal trial of Hollywood madam Heidi Fleiss, which had culminated just two months before Grant’s arrest, was widely seen as sticky and sleazy. The case’s most high-profile participant, Charlie Sheen, was a sweaty and anxious presence on the witness stand. Grant, in comparison, had made Hollywood sex scandals embarrassing and awkward but, believe it or not, almost endearing. It couldn’t have been more perfect if it had been written by Richard Curtis.

“I think he was almost ahead of his time in terms of actually putting his hands up and apologising,” says Ewan Robertson, director of crisis communications at the corporate communications consultancy Citigate Dewe Rogerson. “Something that brands and companies have only realised more recently is actually that, if you do make mistakes, apologising for it isn’t necessarily an issue. The public are far more accepting if you’re open and transparent about it than trying to hide it and cover it up.”

Grant’s humility proved a success – Nine Months made money, Hurley stood by him (while talking of her embarrassment and upset in her own televised sit-down), and Hollywood kept calling. Legally speaking, his punishment was minimal: a $1,000 fine, two years’ summary probation and the compulsory participation in an Aids education programme. If anything, it appeared to boost his profile and revamp his image. The “no sex, please, we’re British” trope, which Grant so often seemed to embrace with his stiff-upper-lip flappiness, had been entirely quelled. He also became a more interesting actor: his most repetitive tics were tempered in Notting Hill (1999), and he was cast brilliantly as sleazy man-children in films such as Bridget Jones’s Diary (2001), About a Boy (2002), Two Weeks Notice (2002) and American Dreamz (2006).

“It might have actually benefited him in the longer term because what he got from it were those more nuanced and interesting love-rat roles,” adds Robertson. “Would he have necessarily been considered for Bridget Jones if he hadn’t gone through what he went through?”

Brown’s life was also changed for the better. While she was undeniably used by the press, paid £100,000 by the News of the World to describe Grant’s penis and pose in Hurley’s iconic safety-pin dress by Versace, she has said that the scandal ultimately rescued her. “Everything worked out for the better,” she explained in a documentary broadcast in 2007, adding that she earned enough money from the scandal to get off the streets and send her children to private school. “It helped me turn it into something positive … I was blessed that it could get me out of that lifestyle.”

Grant’s survival was assisted by his privilege, of course, with white straight men, and in particular white, posh-sounding Englishmen predominantly working in Anglophile America, always more readily forgiven than anyone else. Similarly, it helped that Nine Months was a hit (“That’s the Hollywood way,” he said, with trademark self-deprecation, in 2018. “As long as you make money, they don’t care what you get up to”), but it’s also true that Grant handled the situation spectacularly – owning it, talking about it, and ultimately surpassing it.

It’s a lesson evident throughout celebrity culture today – where apologies typed out on the Notes app and uploaded to a star’s social media are about as ubiquitous as a Hollywood red carpet. The best ones emulate Grant’s. Hands-up honesty about being stupid or ignorant (as seen with Stormzy’s bad tweets, Jason Bateman’s mansplaining or Samantha Bee’s unhelpful use of the word c***) prove far more successful at putting scandals to bed than doubling-down or being oddly dismissive (looking at you, the recently apologetic Lea Michele, Lana Del Rey and Jimmy Kimmel).

As Grant has become more politically outspoken, particularly in his disdain for the Conservative Party and phone hacking within the right-wing press, that infamous mugshot has resurfaced more and more in his Twitter mentions, trolls determining it to be somehow shameful. Or at least something that undermines his… morality? Or sense of right and wrong? … It’s difficult to discern. But it overlooks how open and sincere Grant has always been about a night that was regretful and undeniably cruel to his girlfriend at the time, but certainly at the lower end of a ranking of awful deeds.

“To my dear trolls,” he tweeted last December, alongside his and Brown’s mugshots. “Hope this is helpful. Now you have more time to spend with mummy.” For those who know the history of that fateful summer’s night 25 years ago, it wasn’t a new act of defiance.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks