Why The Bee Sting should be this year’s Booker Prize winner

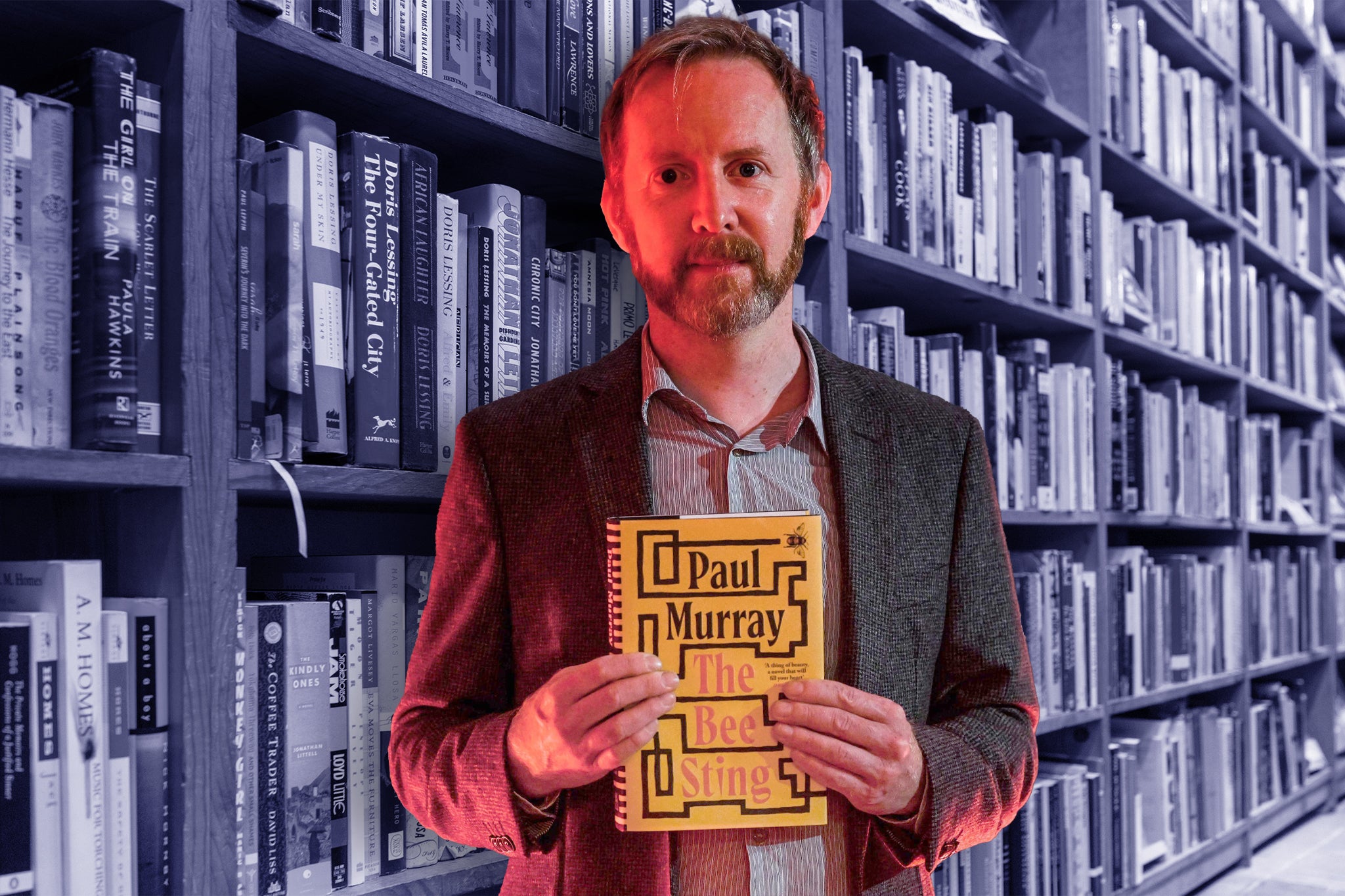

There’s a buzz about one particular novel on this year’s Booker shortlist. Ahead of next week’s winner announcement, John Self explains why Irish writer Paul Murray’s joyously readable 656-page tragicomic family saga is the rightful favourite

With less than two weeks to go before the winner of this year’s Booker Prize for fiction is announced, it’s time – to adopt a cliche surely no Booker novelist would consider – to nail our colours to the mast. This year’s shortlist is not a bad mix, featuring three men called Paul, two women, and one “novel” that is really a collection of stories.

But seeing the discussions on social media and in the press – not to mention reading the actual books – we conclude that there can be only one true result. Whatever the outcome of the judges’ deliberations on 26 November, the People’s Prizewinner must be The Bee Sting by Paul Murray.

Murray, a 47-year-old Irish novelist, has been here before – almost. His cult novel of school life, Skippy Dies, was longlisted in 2010. But he publishes big books that take a long time to write, and 656-pager The Bee Sting is only his second novel since then (and his fourth overall). It was worth the wait. The Bee Sting is far and away the most entertaining of the novels on this year’s Booker shortlist, a fat slab of joyous readability – but which doesn’t stint on emotional depth.

The Bee Sting is a family story, and as Alan Bennett said, all families have a secret: they’re not like other families. In fact, each of the four members of the Barnes family has their own secret, and Murray’s skill is in taking us into each of their heads in turn. On the face of it, the Barneses are a prosperous, middle-class Irish family, where dad Dickie runs a second-hand car business out in the country. But the business is failing, and the stress this puts them under makes all their underlying issues swell toward the surface.

Teenage daughter Cass is a little bit obsessed with her glamorous friend Elaine (“even when she was clipping her toenails, she looked like she was eating a peach”), and desperate to get away from the countryside and into Dublin, where she believes she’ll find real life, and where “everyone doesn’t look like they were made out of mashed potato”. Her brother, PJ, is younger and technology-obsessed, dealing with online life, adolescent hormones and a friend who fancies Cass.

Cass and PJ’s parents have their secrets too. Mum Imelda has never really got over her true love, Dickie’s brother Frank, “the miraculous young sportsman beloved of the whole town”, but Frank died and she married Dickie on the rebound. Needless to say, Dickie has his own regrets, and his story is probably the richest of the lot, full of the wrong turns that led him to “spending his life selling hatchbacks to s***kickers in some godforsaken backwater”.

There are too many good surprises in The Bee Sting to go into more details, but this is a book that blends laugh-out-loud comedy with a real understanding of the tragedy of a thwarted past. “History’s just a pair of knickers,” says one character. “Pull ‘em off and what do you find?” It is full not just of jokes but also perfect descriptions, from the student pub that’s “roasting hot with a smell of Lynx” to a village high street after the financial crash looking like “a mouthful of cavities”.

Murray is brilliant at expressing the passion and explaining the pain of adolescence and beyond, whether depicting Cass and PJ now or Dickie and Imelda in the past. And The Bee Sting fills the reader up with rich detail, with comedy and full-blown feelings, going against the current trend of books where young adulthood is written about in an identikit blank style delivered in affectless prose – a technique that was novel when Sally Rooney did it but has since outstayed its welcome.

But don’t make the mistake of thinking that because The Bee Sting is funny, it can’t be serious. Serious is not the opposite of funny: sombre is the opposite of funny. Here the comic elements lower the reader’s defences and let the serious stuff in, from Cass’s yearnings for Elaine to Dickie’s feelings of failure simply because he can never be his brother Frank.

And god knows we need a bit of a crowd-pleaser right now. The rest of this year’s Booker shortlist certainly won’t provide it, featuring books about ethnic cleansing (Paul Harding’s This Other Eden), prejudice, abuse and guilt (Sarah Bernstein’s Study for Obedience) and a totalitarian dystopia in modern-day Ireland (Paul Lynch’s Prophet Song).

Don’t make the mistake of thinking that because ‘The Bee Sting’ is funny, it can’t be serious

This preference for depressing subject matter is not unusual either in current literature generally – Martin Amis complained in his final book Inside Story about “the intellectual glamour of gloom” – or in the modern Booker Prize. In 2015, even the chair of the judges described the shortlisted books as “pretty grim”. But that was nothing compared to 2020, when one shortlisted title (Diane Cook’s The New Wilderness) opened with a woman giving birth to a stillborn child while fending off a swooping magpie, and the winner (Douglas Stuart’s Shuggie Bain) ground the reader’s emotions to a pulp with the story of alcoholism, poverty and homophobia, and where a notable scene involved the central character singing “The Greatest Love of All” while sinking into a slagheap.

So yes, we need Paul Murray’s book this year. It is a generous, multi-layered, quadruple-decker of serious entertainment that will still have you thinking and smiling long after you finish it. Three cheers for The Bee Sting!

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments