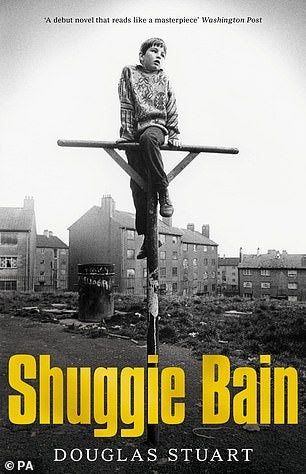

Booker prize winner Douglas Stuart: ‘Homophobia makes you think there’s something broken’

The award-winning author of Shuggie Bain speaks to Martin Chilton about the rejection-filled, 12-year journey to his debut novel and what it was like to grow up gay in a ‘hard man’s world’

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Growing up in 1980s Glasgow, Douglas Stuart was often told that there was something wrong with him. “It is hard in this modern world to make people understand how casual and everyday homophobia was then,” says the author of the magnificent novel Shuggie Bain, which won the Booker Prize last week. “I grew up in what was quite a hard man’s world. I was ‘othered’ at about six years old, before I had any sense of a body or personality or who I am. I was like Shuggie, just a joyful creature going through the world and loving what he loves. There was nothing wrong with me, of course. I was effeminate, sensitive and precocious in the way that Shuggie is. It was adults and children who said, ‘There’s something not quite right about that wee boy.’”

Shuggie Bain, Stuart’s debut novel, tells the heart-wrenching story of the love between Agnes Bain and her son as she sinks into alcoholism and he grapples with his sexuality. It is a compelling story about intimacy, love, class, hardship and family, set in a recession-hit Scotland.

There is a potent scene when Shuggie’s brother Leek tries to teach his younger sibling to “walk like a man”. “That is the power of homophobia,” says 44-year-old Stuart, “it makes the person feel like there is something they can constantly fix that is broken and that if they just address it, if they learn to walk right or change the way they carry themselves, then it can change. That is certainly how I felt for a lot of my life.” For a while, he fought against his own instincts and tried to conform. “Homophobia was a constant in my life. In a lot of ways, it’s a sort of distilled misogyny against anything with a feminine characteristic. I was doing everything I could to conceal that I was effeminate or feminine. Books can be quite sensitive or feminine, so to declare myself as a huge reader was exposure itself. It took a lot of time for me to love myself and to find acceptance. It’s a long, long road. It starts when you find your tribe and some kindred spirits.”

In a quirk of fate, Stuart’s Booker Prize win came during “Anti-Bullying Week” in the UK, at the same time as the reportedly reprehensible behaviour of home secretary Priti Patel was dominating news headlines. “Bullying is a big theme in the book,” says Stuart. “Bullying is devastating. You are the first person that has asked me about bullying so I am stumbling a bit, which is funny because it is such a theme. People aren’t sometimes aware of the damage bullying can do.”

Although we are talking about bullying in the context of the book, rather than about Patel’s case in particular, Stuart’s eloquent portrayal of Shuggie’s suffering is a reminder of why the issue is so important. “I wanted to show in the book that there can be different frequencies to bullying,” he says. “Some of it is very casual and some is incredibly targeted, but the harm it does is immeasurable and the isolation it creates is enormous. Like many of the themes in the book, I never wanted to pitch a tent and say, ‘This is it, look at this theme,’ but bullying increases vulnerability for people, because of the isolation it causes. With Shuggie, it snowballs and keeps the hurt going.”

We chat two days after the Booker triumph, the magnitude of which Stuart says he is “still processing”. There was no glitzy winner’s party. He celebrated at home in Manhattan with his husband Michael Cary, a modern-art curator. “We haven’t seen any friends in New York to celebrate with, because we are all socially distancing, so my husband and I had a little dance around the kitchen to Belle and Sebastian and then I got straight back to work,” says Stuart, who was proud to receive an email of congratulations from first minister Nicola Sturgeon.

He says the most emotional moment was during the dress rehearsals for the ceremony, before he knew he had won. “Last week, I lived through the Kirkus Prize and National Book Awards, when I was shortlisted for both without winning, so I went into the Booker with a sense of, ‘This is how it goes for me,’” says Stuart. “I was genuinely not expecting to win. We haven’t had much human contact recently and when Scottish actor Stuart Campbell read an extract from Shuggie Bain at The Old Vic, I was watching on screen and I thought, ‘This is the greatest moment of my life.’ It was amazing and I had a wee cry. I think people were looking at me on the screen like, ‘What’s that guy crying for in the dress rehearsal?’ and I was thinking, ‘Don’t let me cry in front of Barack Obama.’ Right up to the announcement, I didn’t think it would go my way.”

Shuggie Bain took more than a decade to write and there were bumps along the way. “I was rejected by 32 editors, but rejection is an integral part of being a writer, whether it’s from an agent, a critic or readers,” explains Stuart. “It’s an important lesson for any writer. I’m not sure I understood that at the time but I definitely do now.” He was bolstered by the steadfast support of his husband. “From the first time I sat down to write the very first page, all the way through the process, Michael believed in me. He gave me emotional support and encouragement right from the earliest stage, when I wouldn’t admit to myself that I was trying to write a book because it was just too intimidating.”

Stuart was writing in his spare time while working as a fashion designer, piecing the novel together in early-morning writing stints, or on the subway to and from work, or during summer holidays in the Catskill Mountains. Physical distance from his homeland gave him the mental space to write about his traumatic upbringing, growing up on Sighthill, a large housing estate in Glasgow, as the son of an alcoholic single parent. “America has helped me be a more rounded person,” says Stuart. “I don’t know that I could have written Shuggie if I hadn’t become an immigrant, because it allowed me to look back with more clarity and honesty. I miss Glasgow, and still go home several times a year, but America gave me a belief, and it helped remove me from the British class system, which empowered me to talk about it.”

Stuart never knew his late father – “He was gone when I was about three or four” – and, like Shuggie with Agnes, lost a mother to addiction when he was just a child. “Life is complex,” he says. “I had the unending love and support of my siblings but there came a point after my mother died that I had to go and live in a bedsit. It is only my sister and me now, because I lost my other sibling. She still lives on the south side of Glasgow. Her memories are different. There’s 15 years between us. The condition of our mother was very different from when she was a little girl to when I was a little boy, but my sister is fully supportive of the book and read the manuscript before I sent it out for publication.”

His fortitude was impressive. Stuart was living alone at 16, attending school during the days and working in a DIY superstore in Glasgow to support himself. “I lived in a bedsit room in a rented house. There was a Baby Belling cooker, a refrigerator and a bed. I would put my school uniform on and go to lessons and then come back and put my polyester Homebase uniform on and work for four nights a week. I had Wednesday nights off, and I would work all day Saturday and Sunday. I just had to cling to education.”

Having grown up in a home without books, he is grateful to the English teachers who “just put books in front of me”, including plays by Tennessee Williams, “one of my first loves”. He remembers being bowled over by Thomas Hardy. “His books came at a time when I had peace in my environment and inside of myself,” recalls Stuart. “I was reading all I could and in a lot of ways Shuggie owes a debt to Jude the Obscure and Tess of the d'Urbervilles. With Hardy’s books, it was the first time I thought, ‘God, the whole universe is in this book.’”

Like Shuggie, Stuart grew up in a highly sectarian city, one where it’s dangerous to give the wrong answer when asked whether you follow Celtic or Rangers. Which team does Stuart follow? The author gives a big laugh before replying: “Are you trying to get me kicked out of Glasgow? Neither! I don’t support football. As a gay kid, I was excluded from that altogether. You were asked about those teams and you had to come up with an answer after considering which street you were on and who was asking.”

Agnes gets sober for a time, until she meets a taxi driver called Eugene. “He comes charging in like a white knight on a black hackney, and this is a comment on how women are controlled by men and how the community then didn’t know what to do with single mothers,” says Stuart. “This was also a comment on the stigma of addiction, and how people aren’t allowed to admit they have a problem, even in communities where people drink their face off.”

Glasgow is its own distinct character in Shuggie Bain, which includes a splendid scene set in the Grand Ole Opry nightclub on Govan Road, a place where country music nights are combined with gun slinging contests. “It’s a real place,” says Stuart. “There is a bit of a drag element to it, being able to escape yourself for a minute, which is very powerful. It’s one of my favourite scenes in the book because it shows the part of the Glaswegian spirit that is funny.”

One of the backdrops to the novel is the way Margaret Thatcher’s cuts devastated Glasgow in the 1980s. “I wanted to centre the book around a woman, a very ordinary person, and a queer young boy,” says Stuart. “When I was writing it, I didn’t necessarily know it would have any readers or even be published, so I wrote it for the characters. As a kid, the Thatcher thing was everywhere, but because I was the son of a single mother, it wasn’t necessarily always inside our house. I wanted to keep the book as an intimate love story.”

Stuart is only the second Scot (following James Kelman) to win the Booker in its 51-year history. Kelman’s victory in 1994 with How Late It Was, How Late caused a controversy. “There was such an uproar when he won and it was even dismissed as ‘an act of literary vandalism’,” recalls Stuart. “Young Scottish writers internalised that, but the world has changed and it’s great to see people embracing Shuggie. Diversity in publishing matters. It makes me proud of Britain to see how the culture is shifting.”

Although Stuart remains a proud Scot, he loves life in Manhattan, where he lives a few miles from Donald Trump’s skyscraper base. “I stay away from Trump Tower,” Stuart says. “We were thrilled with the election result. New York does not love Trump at all, on any level. Everyone breathed a sigh of relief. It seemed like reason, fairness and decency was returning to the room. The recent years have empowered a lot of coarse behaviour.”

Stuart has kept busy in the past year, completing his next novel, which is about two 16-year-old boys who are “roped into territorial gangs” in Glasgow. “I wanted to write about masculinity and toxic masculinity and the queer experience under the patriarchy,” explains Stuart. “My two central characters are sweet boys who are marooned, adrift from what the other boys around them expect men to be and the violence, sexuality and hard drinking that women and men expect of them. One of the boys is sent away to make a man of him and it has consequences that ripple throughout the book.”

He is also planning a third novel, set in the north of Scotland. “I keep returning to the themes of love and loss, belonging and loneliness,” he admits. Will he ever return to complete the story of what happens to Shuggie, whom we leave at 15, on the brink of manhood? “I don’t think so,” Stuart replies. “It took 12 years to write, and there was so much catharsis in the book that I was glad to close it.”

Shuggie Bain is published by Picador, priced £14.99

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments