Sophie Haydock: ‘I wanted my novel to reflect Egon Schiele through the eyes of the women he painted’

The journalist’s incendiary debut novel allows readers to speculate about the lives of the Austrian artist’s muses. She tells Helen Brown why she was drawn to his arrogance, his anxiety and the radical poses of his subjects

![Sophie Haydock: ‘The way he [Schiele] ruffled feathers appeals to me’](https://static.the-independent.com/2022/03/11/10/SophieHaydock.jpg)

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.“Can you imagine posing naked for your brother?” boggles Sophie Haydock. “Or stripping to your underwear for your sister’s husband? The more I read about the women who sat for Egon Schiele’s paintings, the more questions I found myself asking…”

With all the Austrian artist’s muses long dead, the 38-year-old journalist could only answer those questions in fiction. Her incendiary debut novel, The Flames, allows readers to speculate about the lives of women whose faces are now world famous, but whose lives remain mysterious. Haydock sweeps readers back to late 19th- and early 20th-century Vienna to tell the stories of four women: the sister, wife, lover and sister-in-law of Egon Schiele (1890–1918). It’s a richly involving narrative that, Haydock has realised, “also works a bit like a personality test. Because the women are all such different personalities, I’ve found readers tend to connect strongly with one in particular”.

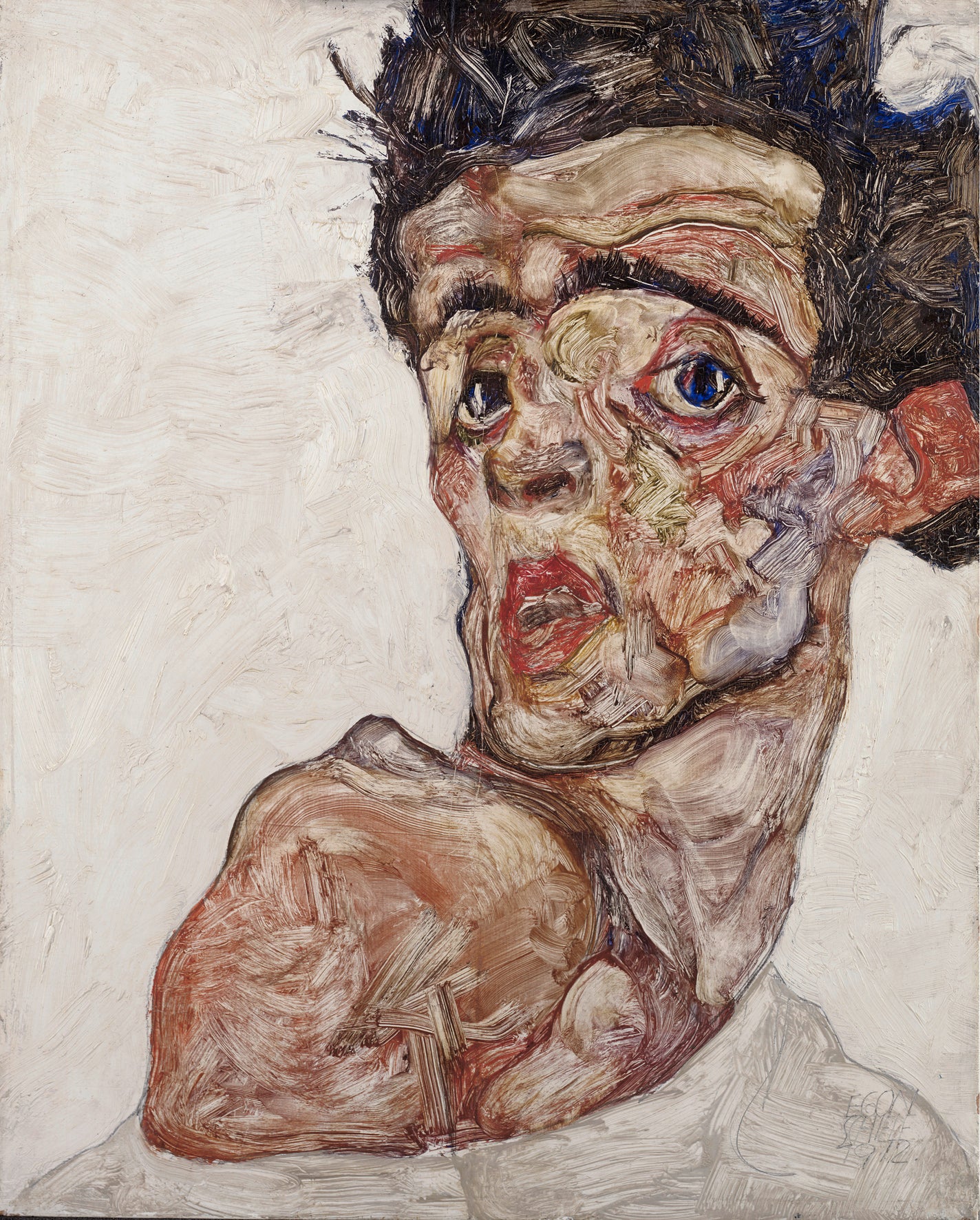

“You can see the intensity of his obsession with sex and death in his work,” she says. “He’s drawn to human flesh and repelled by it. He painted a self-portrait of himself masturbating. There’s a passionate energy there, but always – in the blues and greys and yellows – an awareness of things decomposing. I called my book The Flames because he believed that ‘bodies have their own light, which they consume to live: they burn, they are not lit from the outside’.”

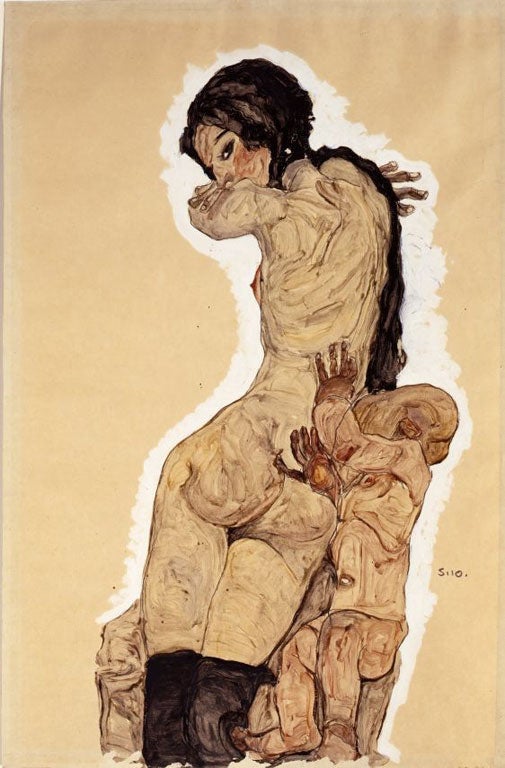

Speaking from her home in Hackney, Haydock confesses that she’d been drawn to Schiele’s explicit, expressionist brushwork for years without wondering who those women were. At university, “like a lot of students”, she had a postcard of his painting of Adele Harms in her black stockings and green vest taped on the wall above her desk. “Her expression is so provocative, smouldering, challenging… I had no idea that she was the sister of Schiele’s wife, Edith.”

Haydock only realised the identity of the sitter at a 2015 visit to The Courtauld Gallery’s Schiele exhibition: The Radical Nude. “I felt a strong connection to the women in the paintings as soon as I went in,” she says. “The models are set in these blank, isolating spaces with a lot of room around them. They’re raw. Some have amputated limbs. They seem trapped in their own minds and skins. I think that’s a representation of his own mental state, his anxiety. It was a reminder that the anxiety that we’re prone to think of as a modern phenomenon is timeless. Schiele was painting in the Vienna of Sigmund Freud, at a time when the big existential questions were being asked.”

It was only at the end of Haydock’s trip to the Courtauld that she read a biographical note informing visitors: Egon Shiele died aged 28, three days after his pregnant wife. “I just knew, in a thunderbolt moment: there’s my book. I wanted to turn the brush back on Schiele and reflect him through the eyes of the women he painted.”

In her author photographs, Haydock looks glossily confident: with blonde locks straight out of a Tamara de Lempicka painting. But in motion she’s softer and more self-doubting, admitting she’s attracted to cocky characters like Schiele because “they’re so different to me”. Over the past seven years, Haydock has become something of an authority on Schiele’s life. She rattles me through the facts, which she says are too often relayed “without emotion” in standard biographies.

Egon Schiele was born in Tulln, in June 1890. His father, Adolf, was a stationmaster who raised his son and two daughters beside the railway tracks, so the artist’s earliest portraits were all of trains. His mother Marie – with whom he had a difficult relationship – suffered a series of miscarriages and stillbirths. Haycock says that “according to Schiele family legend, Schiele’s father caught syphilis from a prostitute on his wedding night because his wife Marie refused to sleep with him”. It seems likely, she adds, that the syphilis contributed to Marie’s fertility problems, and possibly led to the death of Egon’s sister Elvira when she was just 10 years old.

This makes sense of Egon’s later attitude to sexuality and his discomfort around motherhood. Syphilis is a degenerative disease that Haydock believes “sent Adolf mad – he invited imaginary friends over to dinner at the worst of his illness, and also burned the family shares, which left the family destitute after his death”. Adolf Schiele died aged 54, when Schiele was 14, and this had a big impact on the psychology of the shy but rebellious boy.

It’s long been rumoured that Schiele had an incestuous relationship with his sister Gertrude. “When he was 16 and she was 12, they ran away to Trieste together and reportedly shared a single room,” says Haydock. “Egon certainly drew Gerti in the nude, and they had a very close relationship.”

In later life, Gertrude spoke with pride of the deep bond she shared with her brother. In The Flames, Haydock imagines Gertrude’s reaction to his portrait of her: “In it, she’s alone on the page, suspended like a rabbit pulled from a magician’s hat. She appears to be sitting on an invisible chair, her knees tucked tightly together, the curve of her buttocks drawing the eye to the sharp dip of her waist, to her belly button, her breasts. It was excruciating to hold that pose for so long and after a while her fingers had begun to tingle and go numb.”

As a young man, Schiele was mentored by Gustav Klimt. “An often-repeated myth,” says Haydock, “is that aged 17, he approached Klimt to get the older artist’s opinion on the quality of his work, and that Klimt replied: ‘Talent? Yes. Much too much.’” In her novel, Haydock breathes life into another rumour – that Schiele met his first muse and long-term lover, Wally Neuzil, at Klimt’s studio.

The couple were together when Schiele spent 24 days in prison in Neulengbach, charged with indecency in his art, and the seduction and kidnap of a minor (Tatjana von Mossig). The charges of seduction and kidnap were dropped after it was revealed that von Mossig was a runaway who had asked Egon and Wally (pronounced “Vally”) to take her to visit her grandmother, but the one of indecency in his art was upheld, and the judge burnt one of his drawings in the courtroom during the trial.

“Wally inspired some of Schiele’s greatest work,” says Haydock. “But he treated her pretty badly. Schiele wrote a letter to his patron, Arthur Roessler, saying he planned to ‘marry advantageously... not Wally’. While they were together, she signed a document to say she wasn’t in love with him.”

I had to remember that this was a period during which many men wouldn’t have seen their own wives undressed

Schiele moved into a house opposite the well-to-do Harms family in Hietzing, Vienna, in 1914. He is believed to have courted both young women before proposing to Edith, the younger sister. After his proposal, he offered Wally a contract suggesting that they could spend two weeks together each year, with the intention of carrying on as they had been before. She refused and left to be a nurse in the Red Cross, stationed in Sinj, where she died in 1917, aged 23.

“In The Flames, I imagine that the older Harms sister, Adele, might have been in love with Schiele,” says Haydock, “and had an expectation that she’d be the one to marry him. In the 1960s, she told the American art historian Alessandra Comini that she had had an affair with Schiele. All ripe for fiction!”

Much of the drama in Haydock’s book swirls around the relationship between the Harms sisters. Readers will be seduced into the luxurious life they lived in pre-war Vienna, where they were taught Greek, Latin, literature and “conversation”. We read of them preparing for a masked ball across the course of an entire day, bathing in rose petals before dressing in elaborate ballgowns. “Edith’s in the finest pale-green silk, with oozing underskirts and laden with lace. Adele’s is silver brocade with a midnight blue velvet bodice. It pulls in at the waist, showing off her height and slender frame.” But the vintage costume thrills soon give way to squalor as the war brings Vienna to its knees. Readers follow the lives of the sisters as they are brutally stripped (in both senses) of their privilege. Haydock gives both Harms women a degree of sexual agency, while reminding modern readers that this was a period during which women understood very little about their own bodies.

“Women were not fully informed about sexual intercourse or how to get pregnant,” says Haydock. “They didn’t know how to tell if they were pregnant. There was a black hole where the information should have been, which led to fear and shame and confusion. In telling the stories of the Harms sisters, I had to remember that this was a period during which many men wouldn’t have seen their own wives undressed. Sex wouldn’t happen the way it does now. But these women took their clothes off for Egon Schiele. They didn’t know who would see his artwork. That made their choices all the more radical.”

In bringing the Harms sisters to life, “I wanted to breathe life into the suggested rivalries and betrayals of this strong love triangle,” says Haydock. “I felt compelled to offer an alternative version of Edith to the meek, mild, doll-like image that the paintings suggest.” But it’s haughty, clever Adele who jumps most vividly from the page.

Schiele was called up to fight in the First World War just days after his wedding to Edith, and was stationed in Prague. He was given largely administrative duties due to his excellent handwriting and weak heart. Edith went with him. But the couple both died of Spanish flu in 1918, when Edith was six months pregnant with their first child. On the back of the final drawing Schiele ever made (one of her on her deathbed) Edith wrote: “I love you eternally and love you more and more infinitely and immeasurably.”

Adele Harms died, aged 78, in Vienna. Haydock says that “a Schiele scholar told me that by that point poor Adele was penniless, had no family, and practically living on the streets. It made me look back on the artworks Schiele had made of her as a young woman, when she was beautiful, and had the world at her feet, and how she must have suffered after the First World War. Her sister and Egon died so young. It made me wonder if she had any regrets.”

Most bizarrely, Haydock’s novel reveals that Adele Harms is buried in the same plot as Egon Schiele in a graveyard in Vienna. “Edith is buried beside him,” she says, “but Adele’s body shares a plot with him. There is no marker for her. No headstone. Nothing.”

In the century since his death, Schiele has been held up as both a champion of female sexuality and an exploiter. Haycock suspects he was “probably both. They’re not mutually exclusive. He was definitely a controversial character and readers will probably end up feeling differently about him depending on their own experiences. I didn’t want to say: ‘He’s a bad person.’ Or: ‘We should forgive his faults because of his talent.’ I really wanted readers to be able to formulate their own views and ask themselves how his flaws fed into his art. I don’t have all the answers. I’m throwing out the questions.”

Did Haydock finish her novel still able to like Schiele? “I think so, yes…” she mulls. “I’d certainly still love to meet him. He was so handsome. He must have had charisma for people to have responded to him the way they did. I like arrogance. I like people who carry the weight of their convictions with a certain swagger. I’m not really like that, so I’m drawn people who have a sharp awareness of their own talent. The way he ruffled feathers appeals to me.”

But, she adds, “We still need to ask about the impact Schiele’s art and actions had on women. He trod a fine line, and I think he should come under fire for his treatment of the women in his orbit.”

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments