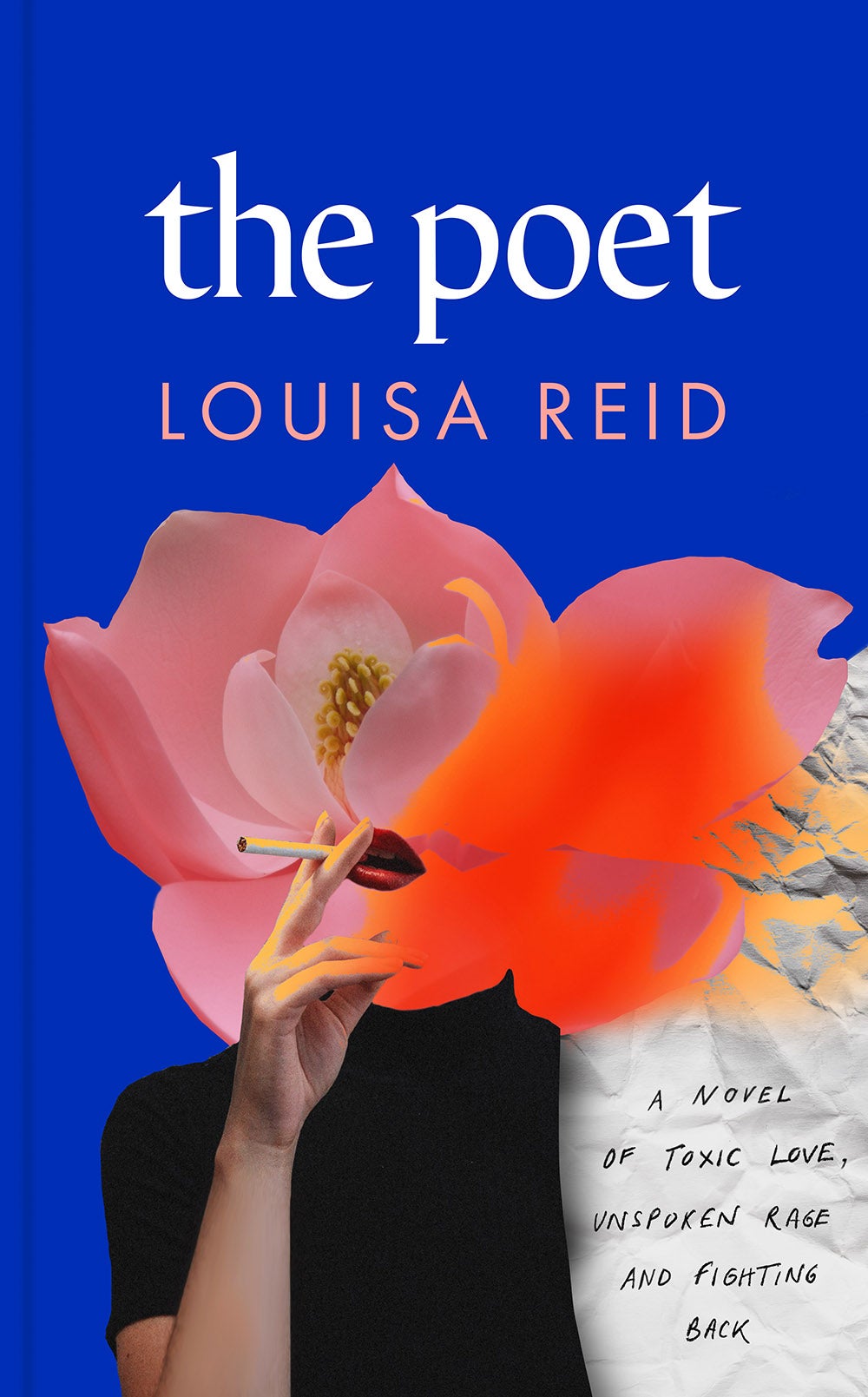

The Poet author Louisa Reid: Posh boys have ‘learned how to make privilege hot’

The YA writer has written a verse novel for adults about the relationship between a graduate and a celebrity lecturer. She talks to Helen Brown about male-female power dynamics, why Depp/Heard means it’s open season for misogyny, and the suppression of women’s voices on the academic syllabus

Your support helps us to tell the story

From reproductive rights to climate change to Big Tech, The Independent is on the ground when the story is developing. Whether it's investigating the financials of Elon Musk's pro-Trump PAC or producing our latest documentary, 'The A Word', which shines a light on the American women fighting for reproductive rights, we know how important it is to parse out the facts from the messaging.

At such a critical moment in US history, we need reporters on the ground. Your donation allows us to keep sending journalists to speak to both sides of the story.

The Independent is trusted by Americans across the entire political spectrum. And unlike many other quality news outlets, we choose not to lock Americans out of our reporting and analysis with paywalls. We believe quality journalism should be available to everyone, paid for by those who can afford it.

Your support makes all the difference.Scrolling! Yes!” enthuses Louisa Reid. “Phones have changed the way people read. Those short lines. Sometimes playful. Sometimes endlessly analysed for deeper meaning. They’ve primed us for poetry.” No wonder, then, that verse novels are trending in the YA (young adult) market. Authors including Sarah Crossan, Elizabeth Acevedo, Jason Reynolds and Kwame Alexander have all used the form to explore the intense emotions of adolescence. Those books inspired Reid – who has published five prose novels for YA readers – to write her first adult novel in verse.

Consequently, The Poet delivers the propulsive kick you get watching a shocking drama unfold on a friend’s social media account. In short, sharp lines it unspools the story of Emma: a 25-year-old Oxford graduate stuck in a toxic relationship with her former lecturer, Tom. Their affair began when he was still her teacher (“that intoxicating thrust of knowledge… my arse on your desk”). Working-class Emma won a coveted poetry prize and published her first book at 21. But four years of Tom’s withering critiques of her work (“you cocked your leg and pissed on my newly painted promise”) have left her unable to write. Instead, she’s stuck at home washing his socks while he bathes in the adulation of his students and leverages his role as a celebrity academic with a blue tick on Twitter. When she googles him she finds:

“You schmooze at me from

a page that lists your accomplishments,

Newsnight appearances,

Radio 4.

I play a recording of a documentary,

watch you stroll through a gallery

with a young artist, then on to a beach.

You are attentive as she speaks,

so charming, so convincing.

I believe every word you say.

That was always my mistake.”

On a videocall from her home in the Greater Manchester town of Altrincham – where she teaches English at a local grammar school – 46-year-old Reid tells me that, after publishing novels for the YA market, it was an adventure writing for adults. She relished nailing posh Tom’s “awful, entitled type”. The book is not based on a real-life affair, she explains, but as a suburban northerner, her own experience at Oxford brought her into contact with her fair share of “big swinging intellects” and posh boys who’d “learned how to make privilege hot”.

“That’s really a thing, isn’t it,” she mulls, in warm Mancunian tones. “Some people think Rishi Sunak is really fit, don’t they. Dishy Rishy. There are women who find Boris attractive,” she winces. “The confidence that comes from their background can become charisma. And Tom has made an art form out of that. When you’re young you crave approbation, and he preys on Emma’s self-doubt. He holds the power and if he says: ‘You’re the real deal, my genius girl’ then she believes it. And when he tells her she’s worthless, she internalises that too.”

Although Reid remembers “lots of normal people” studying alongside her at Hereford College, she became acutely aware of how “the toffs” leveraged class at university. She has tales to tell of friends barred from exclusive dining societies and invite-only photographs taken of “the most attractive female freshers – how vile!” More enduringly, she recalls being set an Anglo-Saxon translation in her first year and “knuckling down to do mine like a good state grammar school girl. But when I came to grab my work from my desk, it had vanished. I discovered that a privately educated lad had just waltzed off with my work and copied it. He just assumed that kind of boring work wasn’t for him and he could take a shortcut. I thought: ‘Bloody hell! What entitlement!’ That stayed with me.”

The casual theft of undervalued women’s work lies at the heart of The Poet. Emma is writing an MA on the work of Victorian poet Charlotte Mew, but Tom (who has previously disdained women’s writing) clocks the vogue for “discovering” forgotten female authors and scores himself a high-profile publishing deal for a book about Mew. Reid says: “He’s a hideous hypocrite who won’t read anything written by contemporary women but thinks he can use and abuse the work of dead women to boost his status as an ‘ubermensch’.”

Limited funds mean we cannot easily modernise book cupboards. More money from the government, please!

Reid shares her protagonist’s fascination with the defiant Mew. Born in 1869, the architect’s daughter was described by Thomas Hardy as the “greatest poetess” he knew and by Siegfried Sassoon as “the only poet who can give me a lump in my throat”. But Reid is annoyed that there’s been much more attention devoted to the “tragic” details of Mew’s life (the fall from wealth to basement dwelling, the siblings committed to insane asylums, the rumours of unrequited lesbian love and the eventual death by suicide) than to her work.

“I love her chutzpah,” says Reid. “I love her lack of interest in social mores and pretensions. ‘Please you, excuse me, good five-o’clock people,’ she wrote, ‘I’ve lost my last hatful of words. And my heart’s in the wood up above the church steeple, I’d rather have tea with the birds.’” Reid is also moved by Mew’s probing of “the insurmountable distances between people”. “‘The Farmer and his bride’ [is] a brilliant example. I read The Stepford Wives recently and was fascinated how Mew’s bride’s flight across the fields, hunted by the community, was replicated in a similar scene in The Stepford Wives. [It’s] so interesting to see women running and pursued in texts across time, trying to evade social forces that seek to imprison them.”

As a teacher, Reid is “shocked and enraged” that the syllabus she’s required to teach is “heavily weighted at GSCE and A-level towards the work of men. Out of 14 poems in the A-level anthology Love through the Ages, only one woman (Rossetti) is included. It’s almost as if women have no opinions on the theme of love or matters of love pre-1900! The GCSE anthology is also weighted in favour of male pens.”

Reid is among the many teachers fighting to redress that balance by introducing students to a broader range of texts. She remembers “introducing some sixth form boys at Highgate [the fee-charging independent school in north London] to Angela Carter’s The Passion of New Eve. They did not like it, and in fact refused to read it. Imagine girls refusing to read texts where women are marginalised or harmed or belittled!” Her ongoing attempt to bring more women’s work into the classroom is frustrated by “limited funds which mean we cannot easily modernise book cupboards. More money from the government, please!”

Reid began writing fiction herself aged 27 and suffered “lots of rejections” before getting her first book deal at 33. She still struggles with imposter syndrome which leaves her feeling “as if I’ve pulled a huge confidence trick on the industry by getting published at all”.

Writing in verse felt like another hurdle. Poetry can feel like an exclusive club, and she was conscious that she “had no qualifications to use the form”. But a visit to the women’s prison at Styal in Cheshire convinced her that poetry “should not be an elitist medium”. She tells me: “The librarian invited me to run a session with a group of women there and we read a poem together called ‘The posh mums are boxing in the square’ by Wayne Holloway-Smith (about the cancer diagnosis of the poet’s mother and how the poetic persona wishes to give her the tenacity to fight). They wrote individual responses, based around what they would give to someone if they could and I found their responses incredibly moving – the women were in tears. For the first time I really saw first-hand – outside of a classroom – the absolute necessity of giving people (especially vulnerable women) a means to express themselves. The women were desperate to write (apart from one woman who wrote nothing and just wept) and to be heard. The librarian typed up and printed out their responses later on and told me they felt great pride in what had been achieved.”

After her visit to Styal, Reid “decided to dive in with the verse and it was such a liberating experience. Just joyful.” It’s poetry that Emma and Tom use to seduce each other. And it’s lines of poetry they hurl “like missiles” as they later seek to destroy each other. Tom’s knowledge and authority (“language, dear,” he chides) squaring up against Emma’s fresh talent, “sharp and dark with the ink of waiting”. You can feel the pleasure Reid felt dancing between references to long-dead poets and the modern vernacular, as when she describes Emma’s avoidance of her work on Mew as “ghosting”.

Once she’d finished, Reid was surprised that resistance from publishers was not to the form but to the topic. One editor rejected her book “on the grounds that the power imbalance between men and women has already been explored quite thoroughly in modern times. I think it’s a perennial issue that needs revisiting especially because there’s a feeling of a backlash against the MeToo movement now.” Reid thinks we can see that backlash in the “truly nasty” social media responses to the Depp/Heard trial. “It’s like open season for misogyny. Structural systems allow men to win arguments against women all the time, but there is a suggestion that this is a great victory for a downtrodden group who are victims of shrewish and deceitful women who set out to harm them. I wonder if we allow popular, talented, charismatic men to get away with awful things if we can justify their behaviour if we demonise a woman enough.”

I finished The Poet, in a late-night binge, and was thrilled by its Coleen Rooney-esque mike-drop ending. I closed it feeling that a copy should be given free to every new university student to help them identify and navigate the power dynamics at play. Reid laughs and says, “that would be very nice! Recognise patterns of abusive behaviour.”

She knows fiction can work in this way because of a friend “who was in a coercively controlling marriage and she told me she only realised her situation after listening to The Archers and following the storyline in which Helen was controlled by the awful Rob. She went on to find her way out of that relationship, thank goodness, so who knows what power art may have in acting as a mirror or door?”

‘The Poet’ by Louisa Reid is in shops from today (9 June) via Doubleday

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments