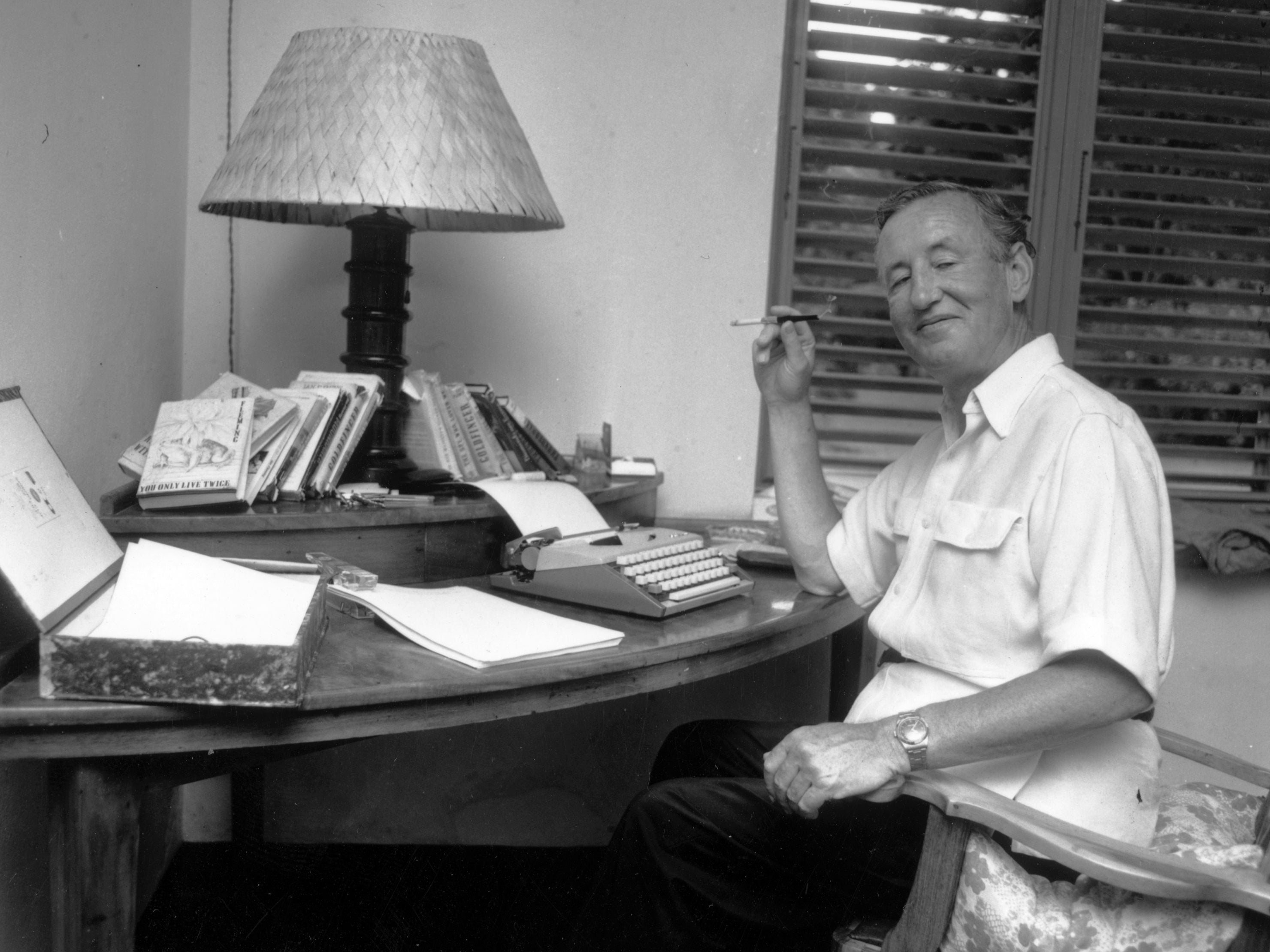

The bounder who created Bond: Ian Fleming’s golden life

He was the ‘Martini-sluicing ladies’ man and louche lounge lizard, who liked a little sado-masochistic sex on the side. And we’re not talking about 007. Robert McCrum is shaken and stirred by an engrossing new biography of Ian Fleming, the enigmatic creator of James Bond

Apart from its length (more than 800 pages), this biography, which cheekily declares its subject “the complete man”, would have pleased Ian Fleming, a master of ruthless brevity and peerless storytelling. Nicholas Shakespeare’s Ian Fleming: The Complete Man is a sustained and engrossing homage to the Olympic icon of a beleaguered Britain, and a writer damned to fame. With scarcely a dull page, it’s a chip off the old block.

WH Auden, who was almost Fleming’s exact contemporary – they are both Edwardian boys – famously observed that “a shilling life will give you all the facts” (how Father beat him, how he ran away...). In that insouciant spirit, Shakespeare embarks on his autopsy of Ian Fleming’s career and reputation by acknowledging how many others have already inspected these remains, a fervent mini-library of books devoted to this author and his alter ego, the British agent with a licence to kill, Commander Bond.

In a crowded morgue, Shakespeare fulfills his claim as the seasoned anatomist with brio. He is a respected novelist, a former literary journalist and biographer of Bruce Chatwin, well-read in the mysteries of press-cuttings and the black arts of biographical interpretation. On this assignment, he does not merely wield the scalpel, but invites an impressive cast of expert witnesses to view the body in question. This post-mortem is steeped in exceptional research, and stitches up the loose ends of Fleming’s story into a satisfying 21st-century biography after a flying start – the shilling life of Fleming’s early years.

Eve, his mother, was vain, selfish and beautiful. His father Val died a hero’s death in the Great War when Ian was nine. Alive or dead, his parents would torment and bewitch him all his life. As one observer put it, “The crazy genes from his mother were always dancing round the strong, silent Scottish genes of his father.” Add to this his junior role in a family of four impossible boys, dominated by the charismatic presence of Peter Fleming, acclaimed author of News from Tartary, and it’s scarcely surprising that, until his mid-thirties, our hero seems little more than a Martini-sluicing ladies’ man and lounge lizard.

Follow this self-centred bounder whom nobody quite understands, and you’ll find that to some he’s “a real snob”; to others “a sadist”; and still others, “inimitable and lovable”. It’s here that Shakespeare executes the first of several revisionist deviations from previous versions, identifying a young man with hidden, well-defended ambitions. His would-be writer emerges as “more mysterious and subtle than anything he wrote”.

Noel Coward said, “Half [Ian’s]world was fantasy.” Possibly a puzzle to himself, by World War Two, Fleming had perfected a camouflage of many identities: from “Fine Lingam” (an anagram), to “the Colonel” and “Walter Mitty”. Shakespeare has fun with these contradictions. Playfully feeding IAN FLEMING into an Enigma machine at Bletchley Park, he’s given top-secret gobbledygook (NVP TGLPYUM), but Bond is not licensed to baffle and the trail goes cold. When war broke out, this strangely animated but enigmatic man found himself in the uniform of a naval commander at a naval intelligence office overlooking the back entrance to 10 Downing Street and, in his own words, “like a round peg in a round hole”.

The war was the making of Ian Fleming, for the present and future. His naval intelligence work with Admiral Godfrey in “Room 39” became the bank of secret service lore at which he could cash cheques of inspiration for the rest of his short life. Shakespeare demonstrates that, far from being the “chocolate sailor” of clubland gossip, Commander Fleming’s gift for covert activity was a “war-winning” contribution. Godfrey’s verdict: “The Allies owe [Fleming] one of those great debts that can never be repaid.”

Encouraged by Churchill, a family friend, Fleming’s addiction to adventure during Britain’s “darkest hour” sponsored those madcap (sometimes suicidal) missions that thrilled the home front and created the fertile imaginative terrain he would exploit with Commander Bond in the 1950s. Admiral Godfrey, one of several models for M, became indispensable to Fleming both as a mentor and as a co-conspirator who relished the future author’s “corkscrew mind”.

The new recruit shared Churchill’s love of gadgets (shades of Q) and “the most fantastic inventions of romance and melodrama”. Only Fleming could have dispatched an agent to disrupt Romanian oil production with a suitcase containing five pounds of high explosive packed in Mackintosh toffee wrappers. His name is also linked to many fabled Operations: GOLDENEYE, MINCEMEAT and JUBILEE, as well as to shadowy adventurers like Rodney Bond. And there were other kinds of jeopardy. It was during the war that he first met and fell headlong in love with Ann, wife of Esmond Harmsworth, scion of The Daily Mail.

Fleming wrote his first Bond novel, Casino Royale, in 1952. He was 44. Now, as this gilded life takes on a darker hue, Shakespeare shifts gear into a superb analysis of the way the astounding success of 007 became, like a classical curse, the thing that corroded Fleming’s life and creativity amidst the privations of post-war Britain.

At root, James Bond was a calculated riposte to Britain’s post-imperial demoralisation from deep within the soul of a frustrated man whose other release was sado-masochistic sex

Atlee’s Britain was cold and deadly. Everyone was worn out. The fruits of victory were the leftovers of wartime blockade: toad-in-the-hole, powdered egg and Spam fritters. But Fleming, the fantasy-master, struck a deal with the Sunday Times, and secured Goldeneye, his Caribbean retreat. For forty-something years, he’d neglected his ambition to write fiction. Now, just days from marrying Ann, and still in competition with his brother, he had the idea of a lifetime while snorkeling, according to Shakespeare. Bond/007 would inspire and irritate the closing fifth of his life.

James Bond has many sources. At root, it was a calculated riposte to Britain’s post-imperial demoralisation from deep within the soul of a frustrated man whose other release was sado-masochistic sex. Shakespeare draws on a web of literary connection to explain Fleming’s catalyst of luck: the wannabe writer’s rendezvous with the zeitgeist. Bond was not an overnight success and history played its part. The shock of Suez (1956) stoked a new appetite for Cold War thrillers. The all-important American market was elusive until, in 1960, the young JFK was discovered to be a fan. Incredibly, Commander Bond was part of the president’s tactical repertoire during the Cuban Missile Crisis (1962), a superpower stand-off to equal any of 007’s adventures.

This cliquey world of London clubs, Fleet Street and the officer’s mess from which Fleming and his commander sprang is now as remote as the Regency. In that tantalising moment when Fleming’s world connected with a new society, Bond became as famous as The Beatles. There’s an argument, which Shakespeare flirts with, that Bond destroyed Fleming, who saw his creation as a nemesis. Persecuted by The Daily Mail, humiliated by his wife’s affair with Hugh Gaitskell, and wracked with heart disease, finally the “undertaker’s wind” claimed him just as he achieved his lifelong ambition: Captain of Royal St George’s golf club. Brief, cryptic, and stoic to the end, NVP TGLPYUM’s last words to the paramedics who raced to save his life were – more shilling life – “I’m sorry to trouble you chaps.”

Only now, 60 years on, can we see his achievement for its charmed rarity. Bond is an immortal of English literature, next to Falstaff, Mrs Bennet, Pickwick, Jeeves and Sherlock Holmes. Whatever Fleming’s bitter late regrets, in Shakespeare’s version, this was a golden guinea of a life.

Ian Fleming: The Complete Man by Nicholas Shakespeare (Harvill Secker, pp. 822, £30) out on 5 October

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks