The brilliant, eccentric life of poet WH Auden

His personal hygiene was questionable, he described himself as ‘not an alcoholic but a drunk’, and he fell out with JRR Tolkien about home decor. Fifty years since the death of WH Auden, Martin Chilton looks back at a legendary British poet still making headlines

Lay your sleeping head, my love/Human on my faithless arm.” “If equal affection cannot be/Let the more loving one be me.” “He was my North, my South, my East and West/My working week and my Sunday rest.” Some of WH Auden’s couplets have the familiarity of poetry catchphrases.

Even as a youngster, Auden had a startling capacity for colourful language. “Mrs Carritt, this tea is like tepid pi**,” he told the shocked mother of his Oxford University friend Gabriel Carritt as she served him breakfast.

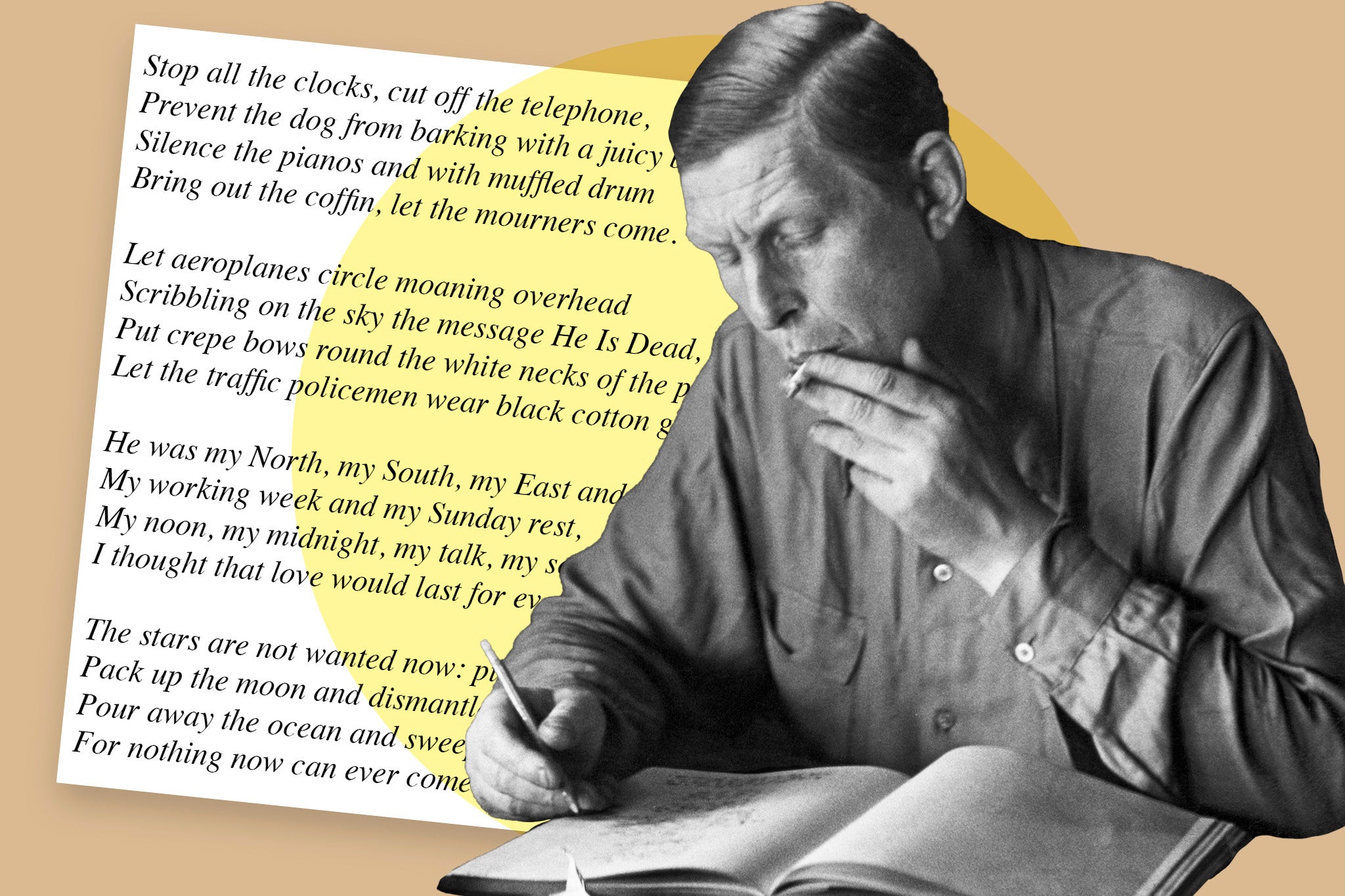

Wystan Hugh Auden, who died 50 years ago, on 29 September 1973, was one of the greatest poets of the 20th century, with verses such as “Lullaby”, “In Memory of WB Yeats”, “Night Mail”, “September 1, 1939” and “Funeral Blues (Stop All the Clocks)” becoming ingrained in popular culture. Auden was a master of the elegy and his poems resonate with readers because they address the essential emotional predicaments that afflict us all. As well as being a literary giant, however, he was undeniably a strange and eccentric man.

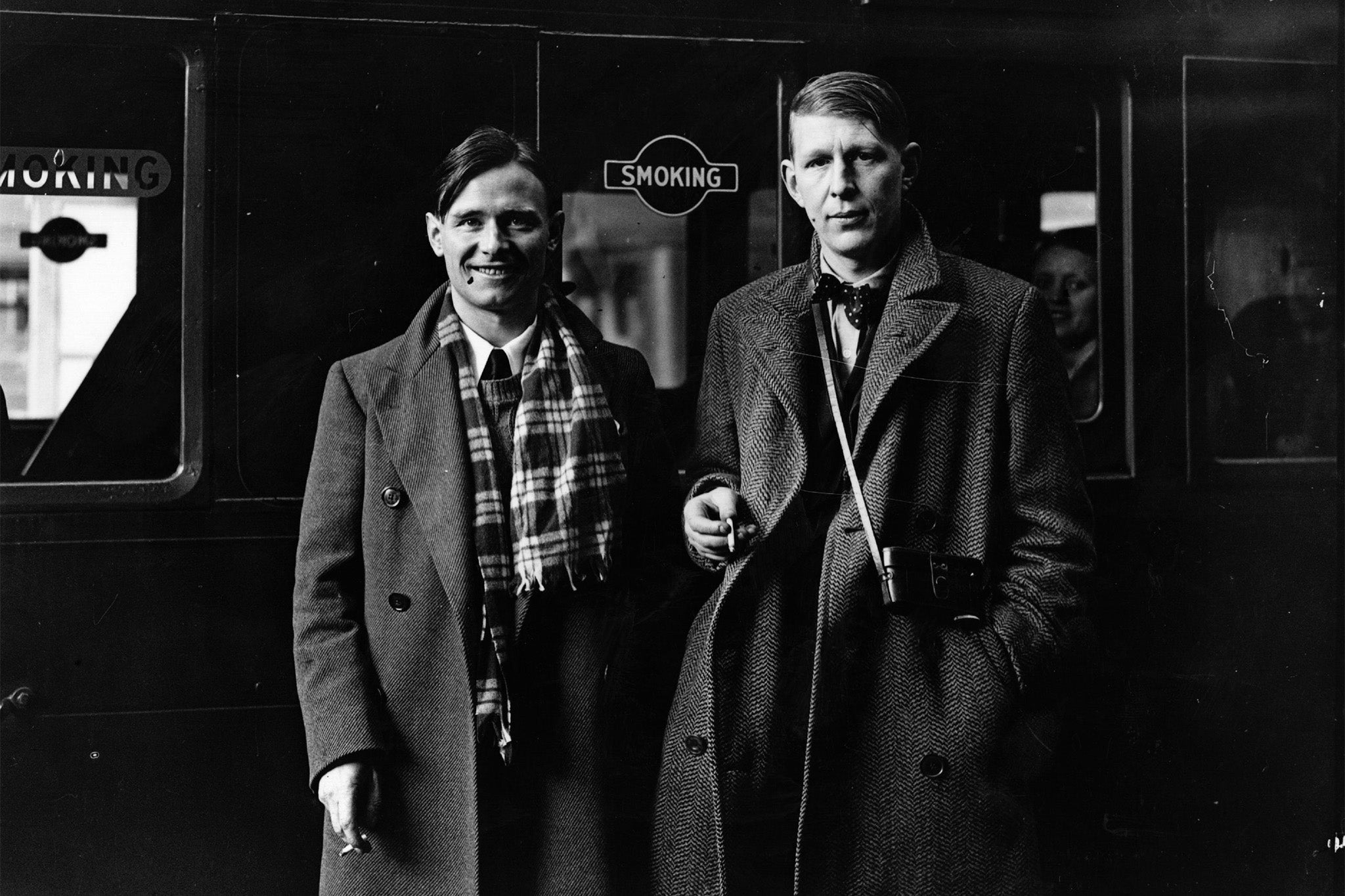

Auden was born in York on 21 February 1907, the youngest of three sons of a physician and a nurse. His 1920s Oxford days – when he flirted with Marxism and was at the centre of what TS Eliot called a “definitely post-war generation” group of trailblazers including Stephen Spender, Christopher Isherwood, Cecil Day-Lewis and Louis MacNeice – became the stuff of literary legend, writers influential enough to often be called simply “the Thirties poets”.

Auden, a clumsy nervous child, who bit his nails down to stumps, found an intellectual home with his young university friends, despite their mockery of his puffy appearance. Day-Lewis described how the young Auden’s “great red flaps of ears stand out on either side of his narrow, scowling, pudding-white face”.

The poet certainly possessed one of the most memorable faces in culture, although people generally commented less on his hazel eyes and pale face and more on the deeply etched, almost melancholy wrinkles, lines that zigzagged his face like a busy road system. Prague-born René Bouché’s memorable portrait and sketch of Auden captures the full force of the poet’s distinctive countenance. Auden himself famously joked that his face looked like “a wedding cake left out in the rain”. David Hockney, who also drew Auden, later joked, “I kept thinking, if his face looks like this, what must his balls look like?”

In fact, from his teenage years, Auden suffered from Touraine‐Solente‐Gole syndrome, a painful, itchy condition in which the skin of the forehead, scalp, hands and feet (although not necessarily the scrotum) becomes thick and furrowed. Incidentally, Bouché’s illustration also shows Auden’s tar-stained fingers. The poet was a lifelong heavy smoker – and amphetamine consumer – rarely pictured without a cigarette in hand.

Although Auden remains a very English poet, he and intermittent lover Isherwood left for New York together in 1939, just before the outbreak of war, and lived most of their lives in America. They were criticised for abandoning their country, especially by Evelyn Waugh, who satirised them in his 1942 novel Put Out More Flags as a pair of hypocritical left-wing poets called Parsnip and Pimpernel, “bravely” standing up to fascism all the way from New York.

It continued to rankle with Waugh that Auden found such success in the United States (he became an American citizen in 1946), where he came to be seen as the voice of his generation. In 1948, Auden won the Pulitzer Prize for his book The Age of Anxiety: A Baroque Eclogue, a masterful work, written in the alliterative style of Old English, which explores with great subtlety the baffling war-torn world in which people were living.

Better known among the general public is his 1936 poem “Funeral Blues” – also known as “Stop All the Clocks” – which Auden repurposed as a cabaret song for vocalist Hedli Anderson. Auden’s poem achieved a popular renaissance in 1994 when it was read by the character Matthew (played by John Hannah) in a eulogy to his dead partner Gareth (Simon Callow) in the hit film Four Weddings and a Funeral. Tell Me the Truth About Love, a pamphlet edition of “Funeral Blues” that appeared with nine other Auden poems, sold more than 275,000 copies in a matter of weeks – sales figures most poets can only dream about. The rousing finale of “Funeral Blues”remains a haunting piece of poetry:

“The stars are not wanted now; put out every one/ Pack up the moon and dismantle the sun,/ Pour away the ocean and sweep up the wood;/ For nothing now can ever come to any good.”

Another dazzling poem from this era is 1938’s “Musée des Beaux Arts”, with its memorable opening stanza:

“About suffering they were never wrong,/ The old Masters: how well they understood/ Its human position: how it takes place/ While someone else is eating or opening a window or just walking dully along;”

Lines of such quality are among the reasons that led critic Christopher Hitchens to praise Auden for possessing three of the qualities that make poets immortal, praising how “he wrote beautifully about love, movingly about war, and he was witty”. One of my favourite Auden works is 1962’s The Dyer’s Hand and Other Essays, a collection of his lectures from his spell in the 1950s as Oxford professor of poetry. The articles are full of humour and wisdom, and prescient about the modern era, as in his remark that “what the mass media offers is not popular art, but entertainment which is intended to be consumed like food, forgotten, and replaced by a new dish.”

Auden requested that his letters be incinerated after his death to make a biography impossible, which fitted with his belief that accounts of the lives of writers were always “superfluous and usually in bad taste”. Enlightened modern readers would surely be amazed by the prurience and condemnation that surrounded Auden’s private life. His affair with Isherwood was the stuff of newspaper gossip in the 1930s, especially after Auden married German Jewish actor Erika Mann, daughter of the writer Thomas. Auden did this so she could obtain a British replacement for the passport the Nazis were about to revoke.

When Auden moved to America, he fell in love with Chester Simon Kallman, 13 years his junior, who became his lifelong lover. Their mutual friend Dorothy Farnan wrote a book about them in 1984 called Auden in Love, which details their tempestuous love affair, arguments and the perennially unfaithful nature of their relationship. While together the pair collaborated on opera librettos for Igor Stravinsky and Benjamin Britten. As well as being a dazzling poet, who claimed to have written in every known meter, Auden was formidably skilled at writing lyrics for the stage.

Kallman seems to have been remarkably calm about Auden’s notoriously low standards of personal hygiene. Auden’s friend Margaret Gardiner called their home on New York’s Lower East Side “a brownish cavern”. Auden remained happy with what he called “my NY nest,” untroubled by the dingy and desolate atmosphere. He never opened the curtains. The maids hired to clean the flat quit on a regular basis. Edmund Wilson and Spender both wrote about the squalor in which Auden lived (he also refused to bathe or shower) and his velvet smoking jacket was always caked with food droppings and spattered with ash.

Auden’s friend, the émigré Russian writer Vassily S Yanovsky, described his bemusement at the “complete mess” in which Auden lived. Once, when Yanovsky used the bathroom, Auden expressed surprise that his friend had used (and flushed) the toilet. “You pee in the toilet?” Auden asked him. When the Russian replied, “Yes, how else?”, Auden laughed and said, “everybody I know does it in the sink. It’s a male’s privilege.”

When Stravinsky’s wife, Vera, visited Auden and Kallman for dinner, she found a bowl of brown gunk in the bathroom and flushed it down the toilet. She later learned it was the evening’s dessert – chocolate pudding Auden had placed on top of the commode to cool. She probably had a lucky escape.

Alongside the grubbiness went Auden’s heavy drinking. The poet became friendly with London-born neurologist Oliver Sacks, who later found fame in 1973 with his book Awakenings. Sacks recalled that Auden was a very heavy drinker, especially of martinis. “He was at pains to say that he was not an alcoholic but a drunk,” Sacks recalled. “I once asked him what the difference was, and he said, ‘An alcoholic has a personality change after a drink or two, but a drunk can drink as much as he wants. I’m a drunk.’”

An alcoholic has a personality change after a drink or two, but a drunk can drink as much as he wants. I’m a drunk

Auden was often blissfully unaware of the impact of his behaviour – and his bluntness. He met JRR Tolkien in 1957 and they remained close. In an interview Auden gave in New York in 1966, he suddenly described Tolkien’s house and decorations as “hideous”. The hurtful comments were reported in English newspapers, but in the aftermath Auden cheerfully ignored Tolkien’s written demands for an apology.

When the National Book Committee awarded Auden America’s National Medal for Literature in 1967, the prizegivers paid eloquent tribute to the Englishman’s impact on world literature. “Auden’s poetry has illuminated our lives and times with grace, wit and vitality,” they said. “His work, branded by the moral and ideological fires of our age, breathes with eloquence, perception and intellectual power.”

Auden’s work in his final years was less revered, however. Philip Larkin called some of his later poetry “a rambling intellectual stew”, and works such as “Doggerel by a Senior Citizen” (“I shall continue till I die/ To pay in cash for what I buy”) were forgettable poems, so far from his earlier astoundingly inventive long-form verse, such as 1941’s New Year Letter, an abstract philosophical poem in Swiftian couplets.

Auden died in his sleep in Vienna at the age of 66, after suffering heart failure and since then his popularity has gone up and down. Following that posthumous spike in popularity in 1994, Auden’s next impact on the cultural landscape came in 2009, when he was a key character in Alan Bennett’s play The Habit of Art, which debuted at the National Theatre. Bennett portrayed Auden as a mordant, lecherous slob. Bennett gave interviews which expressed his disdain for a writer whom he had met while an undergraduate at Oxford in the 1950s. By the time Auden was lecturing at the university in the 1970s he had become, claimed Bennett, “infuriating” and “a bore”.

Auden was back in the news again in 2023, when the release of formerly hidden National Archive records revealed that, shortly before his death, Auden had been rejected by 10 Downing Street as a possible poet laureate. He had been blackballed because of a “filthy” poem he had written in 1948 about gay sex. Conservative prime minister Edward Heath was ready to appoint Auden (after officials told him he was “probably the best poet alive”) until right-wing zealot Ross McWhirter, co-founder of the Guinness Book of Records, intervened. He showed Auden’s poem from an underground publication called Suck. First European Sex Paper No1 to Heath’s principal advisor, Sir John Hewett. The poem, originally titled “The Platonic Blow” (or “The Gobble Poem”), is undoubtedly graphic (“prying the buttocks aside, I nosed my way in/ Down the shaggy slopes. I came to the puckered goal/ his hot spunk spouted in gouts,” wrote Auden) and reading the 34-stanza work seems to have sent McWhirter and Hewitt into a frenzy.

Heath was warned that Auden was the creator of “utterly revolting, pornographic” poems that would “bring disgrace” on the Queen. Heath appointed Sir John Betjeman instead. Auden probably knew none of this when he died and, even if he had, would have probably reiterated his firm belief that a writer’s private life “is, or should be, of no concern to anybody but himself, his family, his friends”.

Auden described himself as a man who had always been “passionately in love with language” and all his quirks and idiosyncrasies are a footnote to his wonderful work. Even half a century on from his death, he remains a compass for brilliant odes. He was modern poetry’s North, South, East and West.

Join our commenting forum

Join thought-provoking conversations, follow other Independent readers and see their replies

Comments

Bookmark popover

Removed from bookmarks